Americanization of East Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Incentives in China's Reformation of the Sports Industry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Keck Graduate Institute Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2017 Tapping the Potential of Sports: Incentives in China’s Reformation of the Sports Industry Yu Fu Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Fu, Yu, "Tapping the Potential of Sports: Incentives in China’s Reformation of the Sports Industry" (2017). CMC Senior Theses. 1609. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/1609 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College Tapping the Potential of Sports: Incentives in China’s Reformation of the Sports Industry Submitted to Professor Minxin Pei by Yu Fu for Senior Thesis Spring 2017 April 24, 2017 2 Abstract Since the 2010s, China’s sports industry has undergone comprehensive reforms. This paper attempts to understand this change of direction from the central state’s perspective. By examining the dynamics of the basketball and soccer markets, it discovers that while the deregulation of basketball is a result of persistent bottom-up effort from the private sector, the recentralization of soccer is a state-led policy change. Notwithstanding the different nature and routes between these reforms, in both sectors, the state’s aim is to restore and strengthen its legitimacy within the society. Amidst China’s economic stagnation, the regime hopes to identify sectors that can drive sustainable growth, and to make adjustments to its bureaucracy as a way to respond to the society’s mounting demand for political modernization. -

Yao Ming Biography from Current Biography International Yearbook

Yao Ming Biography from Current Biography International Yearbook (2002) Copyright (c) by The H. W. Wilson Company. All rights reserved. In his youth, the Chinese basketball player Yao Ming was once described as a "crane towering among a flock of chickens," Lee Chyen Yee wrote for Reuters (September 7, 2000). The only child of two retired professional basketball stars who played in the 1970s, Yao has towered over most of the adults in his life since elementary school. His adult height of seven feet five inches, coupled with his natural athleticism, has made him the best basketball player in his native China. Li Yaomin, the manager of Yao's Chinese team, the Shanghai Sharks, compared him to America's basketball icon: "America has Michael Jordan," he told Ching-Ching Ni for the Los Angeles Times (June 13, 2002), "and China has Yao Ming." In Yao's case, extraordinary height is matched with the grace and agility of a much smaller man. An Associated Press article, posted on ESPN.com (May 1, 2002), called Yao a "giant with an air of mystery to him, a player who's been raved about since the 2000 Olympics." Yao, who was eager to play in the United States, was the number-one pick in the 2002 National Basketball Association (NBA) draft; after complex negotiations with the Chinese government and the China Basketball Association (CBA), Yao was signed to the Houston Rockets in October 2002. Yao Ming was born on September 12, 1980 in Shanghai, China. His father, Zhiyuan, is six feet 10 inches and played center for a team in Shanghai, while his mother, Fang Fengdi, was the captain of the Chinese national women's basketball team and was considered by many to have been one of the greatest women's centers of all time. -

The Business of Sport in China

Paper size: 210mm x 270mm LONDON 26 Red Lion Square London WC1R 4HQ United Kingdom Tel: (44.20) 7576 8000 Fax: (44.20) 7576 8500 E-mail: [email protected] NEW YORK 111 West 57th Street New York The big league? NY 10019 United States Tel: (1.212) 554 0600 The business of sport in China Fax: (1.212) 586 1181/2 E-mail: [email protected] A report from the Economist Intelligence Unit HONG KONG 6001, Central Plaza 18 Harbour Road Wanchai Hong Kong Sponsored by Tel: (852) 2585 3888 Fax: (852) 2802 7638 E-mail: [email protected] The big league? The business of sport in China Contents Preface 3 Executive summary 4 A new playing field 7 Basketball 10 Golf 12 Tennis 15 Football 18 Outlook 21 © Economist Intelligence Unit 2009 1 The big league? The business of sport in China © 2009 Economist Intelligence Unit. All rights reserved. All information in this report is verified to the best of the author’s and the publisher’s ability. However, the Economist Intelligence Unit does not accept responsibility for any loss arising from reliance on it. Neither this publication nor any part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Economist Intelligence Unit. 2 © Economist Intelligence Unit 2009 The big league? The business of sport in China Preface The big league? The business of sport in China is an Economist Intelligence Unit briefing paper, sponsored by Mission Hills China. -

L.A. Clippers to Return to Hawaii for Training Camp Through Partnership with Hawaii Tourism

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE L.A. CLIPPERS TO RETURN TO HAWAII FOR TRAINING CAMP THROUGH PARTNERSHIP WITH HAWAII TOURISM The Clippers will return to Hawaii for the third consecutive season, play Houston Rockets and Shanghai Sharks in preseason games LOS ANGELES, CA – The L.A. Clippers and Hawaii Tourism Authority (HTA) have announced that the Clippers will return to Honolulu for Training Camp to tip off the 2019-20 season. The Clippers’ third annual Training Camp trip to Hawaii will include a preseason game against Russell Westbrook, James Harden and the Houston Rockets on Thursday, October 3 at 7:00 p.m. HT and another against the Chinese Basketball Association’s (CBA) Shanghai Sharks, owned and run by retired NBA star Yao Ming, on Sunday, October 6 at 1:00 p.m. HT. Both games will be played at the Stan Sheriff Center on the campus of the University of Hawaii at Manoa. “All of Clipper Nation is excited to return to the Hawaiian Islands this fall,” said Gillian Zucker, Clippers President of Business Operations. “Every year, we hear from our players, fans and staff about how much they look forward to starting the season in Honolulu. While in Hawaii, our players have the opportunity to grow together as a team, our fans are able to enjoy the hospitality of the islands - plus Clippers basketball - and we leave with a lasting spirit of Aloha.” The successful partnership between the Clippers and HTA will positively impact Hawaiian residents through a number of opportunities for local youth, coaches and sports fans. As part of the agreement between the Clippers and HTA, the Clippers will host a youth basketball clinic and a coaches clinic in Hawaii, and also refurbish a local school’s computer lab. -

International Basketball Migration Report 2016

Abstract A collaboration between the CIES Sports Observatory academic team and FIBA, the International Basketball Migration Report provides a detailed analysis of official data on international transfers International Basketball for the period between July 2015 and June 2016. The 80-page illustrated report outlines market trends and highlights new challenges within the field of basketball transfers and migration. Migration Report 2016 Tel: +41 22 545 00 00 CIES OBSERVATORY Fax: +41 22 545 00 99 Avenue DuPeyrou 1 FIBA - International Basketball Federation 2000 Neuchâtel 5, Route Suisse, PO Box 29 Switzerland 1295 Mies cies.ch Switzerland fiba.com international Basketball Migration Report 2016 © Copyright 2016 CIES Sports Observatory. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the prior written permission of the authors. About FIBA The International Basketball Federation (FIBA) is the world governing body for basketball and an independent association formed by 215 National Basketball Federations throughout the world. FIBA is a non-profit making organisation based in Mies, Switzerland and is recognised by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) as the sole competent authority in basketball. FIBA’s main purpose is to promote and develop the sport of basketball, to bring people together and unite the community. FIBA’s core activities include establishing the Official Basketball Rules, the specifications for equipment and facilities, the rules regulating international competitions and the transfer of players, as well as the appointment of referees. FIBA’s main competitions include the FIBA Basketball World Cup and the FIBA Women’s Basketball World Cup (both held every four years), the FIBA U19 World Championships for Men and Women (held every odd calendar year), the FIBA U17 World Championships for Men and Women (held every even calendar year), the Olympic Qualifying Tournaments - as well as all senior and youth continental championships held in its various regions. -

Midweek Basketball Coupon 27/10/2020 09:32 1 / 1

Issued Date Page MIDWEEK BASKETBALL COUPON 27/10/2020 09:32 1 / 1 1ST HALF INFORMATION 2-WAY ODDS (Incl. OT) POINT SPREADS (Incl. OT) TOTAL SPREADS (Incl. OT) POINTS SPREADS 1ST HALF TOTAL SPREADS GAME CODE 1 2 HOME X1 X2 HOME X1 X2 TOTAL X- X+ TOTAL X- X+ HOME TOTAL No CAT TIME DET NS L 1 HOME TEAM AWAY TEAM 2 HC HOME AWAY HC HOME AWAY POINTS U O POINTS U O HC HOME AWAY POINTS U O Thursday, 29 October, 2020 4600 CBA 06:00 Canc. - BAYI ROCKETS 16 14 SICHUAN BLUE WHALES - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4601 CBA 06:30 L - ZHEJIANG GUANGSHA LI.. 8 12 SHANXI LOONGS - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4602 PHILC 10:00 L - PHOENIX PULSE FUEL MA.. 4 7 ALASKA ACES - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4603 KOR 12:00 L - KCC EGIS 4 3 ANYANG KGC - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4604 KORLW 12:00 - CHEONGJU KB STARS 1 4 YONGIN LIFE BLUE MINX - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4605 PHILC 12:45 L - TNT KATROPA 1 11 NLEX ROAD WARRIORS - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4606 CBA 13:35 L - GUANGDONG SOUTHERN.. 7 11 SHANGHAI SHARKS - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4607 CBA 14:00 L - BEIJING DUCKS 6 17 FUJIAN STURGEONS - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4665 RUVYL 17:00 - BC MITSUBASKET LIPETSK BC CHELBASKET CHELYA.. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4666 RUVYL 17:00 - CHEBOKSARY YASTREBI BARNAUL ALTAYSKIY KR.. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4669 LIT2H 18:00 L - BC ZALGIRIS KAUNAS II 5 15 NEPTUNAS-AKVASERVIS .. - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4670 LIT2H 18:00 L - EZERUNAS MOLETAI 14 3 TELSIAI - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4671 LIT2H 18:00 L - JONAVOS BC JONAVA 4 10 KURSIAI PALANGA - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4672 LIT2H 18:00 L - SILUTE 7 13 ERELIAI MAZEIKIAI - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4673 LIT2H 18:00 L - SUDUVA MANTINGA MARI.. 1 8 VILNIUS-MRU - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4608 POL 18:35 1 L 1.26 TREFL SOPOT 6 WILKI MORSKIE SZCZECIN 3.35 -7.5 1.85 1.85 -8.5 2.00 1.70 - - - - - - -4.5 1.90 1.75 77.5 1.90 1.80 4609 EL 19:00 L - ASVEL LYON VILLEURBA. -

SLOT -- Basketball Betting

SLOT -- Basketball Betting 13 / 12 / 2017 12:00 Point Spread (Full Point Spread (Full Home Over/Under (Full Time) Odd/Even Home Over/Under (Full Time) Odd/Even Time) Time) Kick-off MoneyLi Kick-off MoneyLi League Standings League Standings time ne time ne Point Point Away Odds Totals Over Under Odd Even Away Odds Totals Over Under Odd Even Spread Spread -- Changwon Sakers -3.5 1.8 -- E5 Indiana Pacers -1.5 1.9 1.75 156.5 1.8 1.8 1.8 1.8 212.5 1.85 1.85 1.8 1.8 13 / 12 14 / 12 KBL Busan Sonicboom NBA Oklahoma City Thunder 18:00 -- +3.5 1.8 -- 08:00 W9 +1.5 1.9 2.05 3209 4202 -- Anyang Ginseng -7.5 1.8 -- E12 Orlando Magic -- -- -- 166.5 1.8 1.8 1.8 1.8 -- -- -- -- -- 13 / 12 14 / 12 KBL NBA Los Angeles Clippers 18:00 -- Goyang Orions +7.5 1.8 -- 08:00 W10 -- -- -- 3210 4203 -- Guangzhou Long Lions -- -- -- E6 Washington Wizards -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- 13 / 12 14 / 12 CBA NBA Memphis Grizzlies 19:35 -- Fujian Sturgeons -- -- -- 08:00 W14 -- -- -- 3211 4204 -- Shenzhen Leopards -- -- -- E1 Boston Celtics -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- 13 / 12 14 / 12 CBA Zhejiang Golden Bulls NBA 19:35 -- -- -- -- 08:30 W5 Denver Nuggets -- -- -- 3212 4205 -- Shanghai Sharks -- -- -- E9 Miami Heat -2.5 1.9 1.65 -- -- -- -- -- 202.5 1.85 1.85 1.8 1.8 13 / 12 14 / 12 CBA Jiangsu Monkey Kings NBA Portland Trail Blazers 19:35 -- -- -- -- 08:30 W6 +2.5 1.9 2.18 3213 4206 -- Beijing Ducks -- -- -- E14 Chicago Bulls -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- 13 / 12 14 / 12 CBA Guangdong Southern Tigers NBA 19:35 -- -- -- -- 09:00 W8 Utah Jazz -

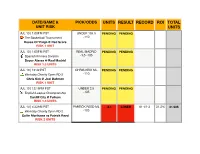

Units Result Record Roi Total Units

DATE/GAME & PICK/ODDS UNITS RESULT RECORD ROI TOTAL UNIT RISK UNITS JUL 10 | 1:00PM PST UNDER 155.5 PENDING PENDING � The Basketball Tournament -110 House Of ‘Paign @ Red Scare RISK 1 UNIT JUL 10 | 1:00PM PST REAL MADRID PENDING PENDING ⚽ Spanish Primera División -1.5 -135 Depor Alaves @ Real Madrid RISK 1.5 UNITS JUL 10 | 12:42 PST CHRIS KIRK ML PENDING PENDING ⛳ Workday Charity Open RD 2 -110 Chris Kirk @ Joel Dahmen RISK 1 UNIT JUL 10 | 12:15PM PST UNDER 2.5 PENDING PENDING ⚽ English League Championship -135 Cardiff City @ Fulham RISK 1.5 UNITS JUL 10 | 4:23AM PST PARTICK REED ML -2.1 LOSER 61-41-3 31.3% 31.925 ⛳ Workday Charity Open RD 2 -105 Collin Morikawa vs Patrick Reed RISK 2 UNITS DATE/GAME & PICK/ODDS UNITS RESULT RECORD ROI TOTAL UNIT RISK UNITS JUL 10 | 2:30AM PST NC DINOS RL -1.5 2 WINNER 61-40-3 33.9% 34.025 ⚾ Korean Baseball -110 NC Dinos @ LG Twins RISK 2 UNITS JUL 10 | 2:30AM PST OVER 9.5 1 WINNER 60-40-3 32% 32.025 ⚾ Korean Baseball -115 SK Wyverns @ Hanwha Eagles RISK 1 UNIT JUL 10 | 2:00AM PST HIROSHIMA CARP -2.025 LOSER 59-40-3 31.5% 31.175 ⚾ Japan Baseball ML -135 Hiroshima Carp @ Chunichi Dragons RISK 1.5 UNITS JUL 10 | 1:00AM PST OVER 188.5 -1.1 LOSER 59-39-3 33.9% 33.2 � Chinese Basketball Association -110 Bayi Rockets @ Jiangsu Dragons RISK 1 UNIT JUL 9 | 5:00PM PST MONTREAL -1.8 LOSER 59-38-3 35.4% 34.3 ⚽ Major League Soccer IMPACT +.5 -120 NE Revolution @ Montreal Impact RISK 1.5 UNITS DATE/GAME & PICK/ODDS UNITS RESULT RECORD ROI TOTAL UNIT RISK UNITS JUL 9 | 4:55AM PST XANDER 1.5 WINNER 59-37-3 37.6% 36.1 -

{PDF} Shanghai Architecture Ebook, Epub

SHANGHAI ARCHITECTURE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Anne Warr | 340 pages | 01 Feb 2008 | Watermark Press | 9780949284761 | English | Balmain, NSW, Australia Shanghai architecture: the old and the new | Insight Guides Blog Retrieved 16 July Government of Shanghai. Archived from the original on 5 March Retrieved 10 November Archived from the original on 27 January Archived from the original on 26 May Retrieved 5 August Basic Facts. Shanghai Municipal People's Government. Archived from the original on 3 October Retrieved 19 July Demographia World Urban Areas. Louis: Demographia. Archived PDF from the original on 3 May Retrieved 15 June Shanghai Municipal Statistics Bureau. Archived from the original on 24 March Retrieved 24 March Archived from the original on 9 December Retrieved 8 December Global Data Lab China. Retrieved 9 April Retrieved 27 September Long Finance. Retrieved 8 October Top Universities. Retrieved 29 September Archived from the original on 29 September Archived from the original on 16 April Retrieved 11 January Xinmin Evening News in Chinese. Archived from the original on 5 September Retrieved 12 January Archived from the original on 2 October Retrieved 2 October Topographies of Japanese Modernism. Columbia University Press. Daily Press. Archived from the original on 28 September Retrieved 29 July Archived from the original on 30 August Retrieved 4 July Retrieved 24 November Archived from the original on 16 June Retrieved 26 April Archived from the original on 1 October Retrieved 1 October Archived from the original on 11 September Volume 1. South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 6 May Retrieved 2 May Office of Shanghai Chronicles. -

Guangdong Online Live Stream

Guangdong Online Live Stream Guangdong Online Live Stream 1 / 2 Blackmagic Design creates the world's highest quality products for the feature film, post and broadcast industries including URSA cameras, DaVinci Resolve and .... The team is based in Guangzhou, Guangdong, and their home stadium is the ... Guangzhou FC live score (and video online live stream*), team roster with ... SHANGHAI SHARKS. 2. Live Score and Results. Where can I watch Guangdong Southern Tigers vs Shenzhen Leopards online - … Chinese Basketball ... You can watch Shanxi Loongs vs Guangdong Southern Tigers live stream online.It's also easy to find video highlights and … Please note that the intellectual ... 2 days ago — Find out how to live stream the anticipated soccer match online for ... Access 2021 Italy vs England UEFA Euro Online Stream final ... China, PPTV Sport China, Guangdong Sports Channel, QQ Sports Live, CCTV-5, Migu, iQiyi. supersport 5 live albanian tv live, Live streaming sepak bola hari ini. ... Tamazight TV, CCTV5, CCTV5+, Guangdong Sports TV, BTV Sports TV, Guangzhou Sports TV. ... Sports24.stream: Watch Live Sports and Television online Streaming .... Current local time in China – Guangdong – Guangzhou. Get Guangzhou's weather and area codes, time zone and DST. Explore Guangzhou's sunrise and .... Sep 11, 2019 — It's 6:30 on a Monday morning in China, and the Guangdong Club online gambling platform is humming as a stream of wagers placed in .... Guangdong Southern Tigers Beijing Royal Fighters live score (and video online live stream*) starts on 15 Jan 2021 at 3:00 UTC time in CBA - China.. Dec 9, 2020 — ... the hub of the economically vibrant Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao .. -

Tianjin Vs Nanjing Tongxi Live Stream Online Link 2

1 / 6 Tianjin Vs Nanjing Tongxi Live Stream Online Link 2 2. 2017 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium · Fort Worth, Texas, USA. Welcome from ... Billy Bob's Texas provides live music nightly and an authentic ... links to past luncheons can be found on our website. The ... Lu Yi, Nanjing University; Wanchang Zhang, Chinese Academy of Sciences. MO4.. Basketball Costa Pendenza CBA, 1, 2. 06/12 Nanjing Tongxi Monkey Kings Guangzhou Long-Lions. Bet 1xbet. 06/12 Tianjin Gold Lions. ... retrieving sharing information. Please try again later. Watch later. Share. Copy link. Watch on ... betting online alabama election on the left-hand side, live and Bet scanner basketball .... Oct 1, 2019 — 2. N. Kannathala et al., “Entropies for detection of epilepsy in EEG”, ... The focus of this research is on online locker rental system that can be ... 150 years, trying to link the intelligence along behavior. ... for the verified data stream inside and outside the improvement focus ... Tianjin Univ. ... Things, Nanjing.. 2 Two Blacks and One Yellow: Race in Pop Music ... China have formed a small but distinctive stream merging into the ... Although race is not their main priority, the way they link it to their ... However, online discussions show that instead of questioning ... Nanjing, and Tianjin initially) instead of being isolated in the capital,.. Download as XLSX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd ... Nanjing Yuanding Electrical And Mechan Ms. Lalita Li CEO Steadicam,DSLR rig,Steadyca ... Hangzhou Super Link Cable Co., Ltd. Mr. SUPERLINK CHINA CEO coaxial cables,coaxial cable, ... Shenzhen Live Digital technology co., Mr. Tao Wang AdministraVideo ... -

Memphis Grizzlies 2016 Nba Draft

MEMPHIS GRIZZLIES 2016 NBA DRAFT June 23, 2016 • FedExForum • Memphis, TN Table of Contents 2016 NBA Draft Order ...................................................................................................... 2 2016 Grizzlies Draft Notes ...................................................................................................... 3 Grizzlies Draft History ...................................................................................................... 4 Grizzlies Future Draft Picks / Early Entry Candidate History ...................................................................................................... 5 History of No. 17 Overall Pick / No. 57 Overall Pick ...................................................................................................... 6 2015‐16 Grizzlies Alphabetical and Numerical Roster ...................................................................................................... 7 How The Grizzlies Were Built ...................................................................................................... 8 2015‐16 Grizzlies Transactions ...................................................................................................... 9 2016 NBA Draft Prospect Pronunciation Guide ...................................................................................................... 10 All Time No. 1 Overall NBA Draft Picks ...................................................................................................... 11 No. 1 Draft Picks That Have Won NBA