Impact of Intervals on the Emotional Effect in Western Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Jazz Chord Symbols Here I Use the More Explicit Abbreviation 'Maj7' for Major Seventh

Common jazz chord symbols Here I use the more explicit abbreviation 'maj7' for major seventh. Other common abbreviations include: C² C²7 CMA7 and CM7. Here I use the abbreviation 'm7' for minor seventh. Other common abbreviations include: C- C-7 Cmi7 and Cmin7. The variations given for Major 6th, Major 7th, Dominant 7th, basic altered dominant and minor 7th chords in the first five systems are essentially interchangeable, in other words, the 'color tones' shown added to these chords (9 and 13 on major and dominant seventh chords, 9, 13 and 11 on minor seventh chords) are commonly added even when not included in a chord symbol. For example, a chord notated Cmaj7 is often played with an added 6th and/or 9th, etc. Note that the 11th is not one of the basic color tones added to major and dominant 7th chords. Only #11 is added to these chords, which implies a different scale (lydian rather than major on maj7, lydian dominant rather than the 'seventh scale' on dominant 7th chords.) Although color tones above the seventh are sometimes added to the m7b5 chord, this chord is shown here without color tones, as it is often played without them, especially when a more basic approach is being taken to the minor ii-V-I. Note that the abbreviations Cmaj9, Cmaj13, C9, C13, Cm9 and Cm13 imply that the seventh is included. Major triad Major 6th chords C C6 C% w ww & w w w Major 7th chords (basic structure: root, 3rd, 5th and 7th of root's major scale) 4 CŒ„Š7 CŒ„Š9 CŒ„Š13 w w w w & w w w Dominant seventh chords (basic structure: root, 3rd, 5th and b7 of root's major scale) 7 C7 C9 C13 w bw bw bw & w w w basic altered dominant 7th chords 10 C7(b9) C7(#5) (aka C7+5 or C+7) C7[äÁ] bbw bw b bw & w # w # w Minor 7 flat 5, aka 'half diminished' fully diminished Minor seventh chords (root, b3, b5, b7). -

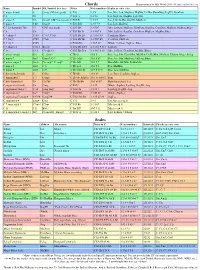

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM Chords Charts written by Mal Webb 2014-18 http://malwebb.com Name Symbol Alt. Symbol (best first) Notes Note numbers Scales (in order of fit). C major (triad) C Cmaj, CM (not good) C E G 1 3 5 Ion, Mix, Lyd, MajPent, MajBlu, DoHar, HarmMaj, RagPD, DomPent C 6 C6 C E G A 1 3 5 6 Ion, MajPent, MajBlu, Lyd, Mix C major 7 C∆ Cmaj7, CM7 (not good) C E G B 1 3 5 7 Ion, Lyd, DoHar, RagPD, MajPent C major 9 C∆9 Cmaj9 C E G B D 1 3 5 7 9 Ion, Lyd, MajPent C 7 (or dominant 7th) C7 CM7 (not good) C E G Bb 1 3 5 b7 Mix, LyDom, PhrDom, DomPent, RagCha, ComDim, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 9 C9 C E G Bb D 1 3 5 b7 9 Mix, LyDom, RagCha, DomPent, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 7 sharp 9 C7#9 C7+9, C7alt. C E G Bb D# 1 3 5 b7 #9 ComDim, Blues C 7 flat 9 C7b9 C7alt. C E G Bb Db 1 3 5 b7 b9 ComDim, PhrDom C 7 flat 5 C7b5 C E Gb Bb 1 3 b5 b7 Whole, LyDom, SupLoc, Blues C 7 sharp 11 C7#11 Bb+/C C E G Bb D F# 1 3 5 b7 9 #11 LyDom C 13 C 13 C9 add 13 C E G Bb D A 1 3 5 b7 9 13 Mix, LyDom, DomPent, MajBlu, Blues C minor (triad) Cm C-, Cmin C Eb G 1 b3 5 Dor, Aeo, Phr, HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin, MinPent, Ukdom, Blues, Pelog C minor 7 Cm7 Cmin7, C-7 C Eb G Bb 1 b3 5 b7 Dor, Aeo, Phr, MinPent, UkDom, Blues C minor major 7 Cm∆ Cm maj7, C- maj7 C Eb G B 1 b3 5 7 HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin C minor 6 Cm6 C-6 C Eb G A 1 b3 5 6 Dor, MelMin C minor 9 Cm9 C-9 C Eb G Bb D 1 b3 5 b7 9 Dor, Aeo, MinPent C diminished (triad) Cº Cdim C Eb Gb 1 b3 b5 Loc, Dim, ComDim, SupLoc C diminished 7 Cº7 Cdim7 C Eb Gb A(Bbb) 1 b3 b5 6(bb7) Dim C half diminished Cø -

Naming a Chord Once You Know the Common Names of the Intervals, the Naming of Chords Is a Little Less Daunting

Naming a Chord Once you know the common names of the intervals, the naming of chords is a little less daunting. Still, there are a few conventions and short-hand terms that many musicians use, that may be confusing at times. A few terms are used throughout the maze of chord names, and it is good to know what they refer to: Major / Minor – a “minor” note is one half step below the “major.” When naming intervals, all but the “perfect” intervals (1,4, 5, 8) are either major or minor. Generally if neither word is used, major is assumed, unless the situation is obvious. However, when used in naming extended chords, the word “minor” usually is reserved to indicate that the third of the triad is flatted. The word “major” is reserved to designate the major seventh interval as opposed to the minor or dominant seventh. It is assumed that the third is major, unless the word “minor” is said, right after the letter name of the chord. Similarly, in a seventh chord, the seventh interval is assumed to be a minor seventh (aka “dominant seventh), unless the word “major” comes right before the word “seventh.” Thus a common “C7” would mean a C major triad with a dominant seventh (CEGBb) While a “Cmaj7” (or CM7) would mean a C major triad with the major seventh interval added (CEGB), And a “Cmin7” (or Cm7) would mean a C minor triad with a dominant seventh interval added (CEbGBb) The dissonant “Cm(M7)” – “C minor major seventh” is fairly uncommon outside of modern jazz: it would mean a C minor triad with the major seventh interval added (CEbGB) Suspended – To suspend a note would mean to raise it up a half step. -

The 17-Tone Puzzle — and the Neo-Medieval Key That Unlocks It

The 17-tone Puzzle — And the Neo-medieval Key That Unlocks It by George Secor A Grave Misunderstanding The 17 division of the octave has to be one of the most misunderstood alternative tuning systems available to the microtonal experimenter. In comparison with divisions such as 19, 22, and 31, it has two major advantages: not only are its fifths better in tune, but it is also more manageable, considering its very reasonable number of tones per octave. A third advantage becomes apparent immediately upon hearing diatonic melodies played in it, one note at a time: 17 is wonderful for melody, outshining both the twelve-tone equal temperament (12-ET) and the Pythagorean tuning in this respect. The most serious problem becomes apparent when we discover that diatonic harmony in this system sounds highly dissonant, considerably more so than is the case with either 12-ET or the Pythagorean tuning, on which we were hoping to improve. Without any further thought, most experimenters thus consign the 17-tone system to the discard pile, confident in the knowledge that there are, after all, much better alternatives available. My own thinking about 17 started in exactly this way. In 1976, having been a microtonal experimenter for thirteen years, I went on record, dismissing 17-ET in only a couple of sentences: The 17-tone equal temperament is of questionable harmonic utility. If you try it, I doubt you’ll stay with it for long.1 Since that time I have become aware of some things which have caused me to change my opinion completely. -

MTO 0.7: Alphonce, Dissonance and Schumann's Reckless Counterpoint

Volume 0, Number 7, March 1994 Copyright © 1994 Society for Music Theory Bo H. Alphonce KEYWORDS: Schumann, piano music, counterpoint, dissonance, rhythmic shift ABSTRACT: Work in progress about linearity in early romantic music. The essay discusses non-traditional dissonance treatment in some contrapuntal passages from Schumann’s Kreisleriana, opus 16, and his Grande Sonate F minor, opus 14, in particular some that involve a wedge-shaped linear motion or a rhythmic shift of one line relative to the harmonic progression. [1] The present paper is the first result of a planned project on linearity and other features of person- and period-style in early romantic music.(1) It is limited to Schumann's piano music from the eighteen-thirties and refers to score excerpts drawn exclusively from opus 14 and 16, the Grande Sonate in F minor and the Kreisleriana—the Finale of the former and the first two pieces of the latter. It deals with dissonance in foreground terms only and without reference to expressive connotations. Also, Eusebius, Florestan, E.T.A. Hoffmann, and Herr Kapellmeister Kreisler are kept gently off stage. [2] Schumann favours friction dissonances, especially the minor ninth and the major seventh, and he likes them raw: with little preparation and scant resolution. The sforzato clash of C and D in measures 131 and 261 of the Finale of the G minor Sonata, opus 22, offers a brilliant example, a peculiarly compressed dominant arrival just before the return of the main theme in G minor. The minor ninth often occurs exposed at the beginning of a phrase as in the second piece of the Davidsbuendler, opus 6: the opening chord is a V with an appoggiatura 6; as 6 goes to 5, the minor ninth enters together with the fundamental in, respectively, high and low peak registers. -

A Group-Theoretical Classification of Three-Tone and Four-Tone Harmonic Chords3

A GROUP-THEORETICAL CLASSIFICATION OF THREE-TONE AND FOUR-TONE HARMONIC CHORDS JASON K.C. POLAK Abstract. We classify three-tone and four-tone chords based on subgroups of the symmetric group acting on chords contained within a twelve-tone scale. The actions are inversion, major- minor duality, and augmented-diminished duality. These actions correspond to elements of symmetric groups, and also correspond directly to intuitive concepts in the harmony theory of music. We produce a graph of how these actions relate different seventh chords that suggests a concept of distance in the theory of harmony. Contents 1. Introduction 1 Acknowledgements 2 2. Three-tone harmonic chords 2 3. Four-tone harmonic chords 4 4. The chord graph 6 References 8 References 8 1. Introduction Early on in music theory we learn of the harmonic triads: major, minor, augmented, and diminished. Later on we find out about four-note chords such as seventh chords. We wish to describe a classification of these types of chords using the action of the finite symmetric groups. We represent notes by a number in the set Z/12 = {0, 1, 2,..., 10, 11}. Under this scheme, for example, 0 represents C, 1 represents C♯, 2 represents D, and so on. We consider only pitch classes modulo the octave. arXiv:2007.03134v1 [math.GR] 6 Jul 2020 We describe the sounding of simultaneous notes by an ordered increasing list of integers in Z/12 surrounded by parentheses. For example, a major second interval M2 would be repre- sented by (0, 2), and a major chord would be represented by (0, 4, 7). -

The Lost Harmonic Law of the Bible

The Lost Harmonic Law of the Bible Jay Kappraff New Jersey Institute of Technology Newark, NJ 07102 Email: [email protected] Abstract The ethnomusicologist Ernest McClain has shown that metaphors based on the musical scale appear throughout the great sacred and philosophical works of the ancient world. This paper will present an introduction to McClain’s harmonic system and how it sheds light on the Old Testament. 1. Introduction Forty years ago the ethnomusicologist Ernest McClain began to study musical metaphors that appeared in the great sacred and philosophical works of the ancient world. These included the Rg Veda, the dialogues of Plato, and most recently, the Old and New Testaments. I have described his harmonic system and referred to many of his papers and books in my book, Beyond Measure (World Scientific; 2001). Apart from its value in providing new meaning to ancient texts, McClain’s harmonic analysis provides valuable insight into musical theory and mathematics both ancient and modern. 2. Musical Fundamentals Figure 1. Tone circle as a Single-wheeled Chariot of the Sun (Rg Veda) Figure 2. The piano has 88 keys spanning seven octaves and twelve musical fifths. The chromatic musical scale has twelve tones, or semitone intervals, which may be pictured on the face of a clock or along the zodiac referred to in the Rg Veda as the “Single-wheeled Chariot of the Sun.” shown in Fig. 1, with the fundamental tone placed atop the tone circle and associated in ancient sacred texts with “Deity.” The tones are denoted by the first seven letters of the alphabet augmented and diminished by and sharps ( ) and flats (b). -

Shifting Exercises with Double Stops to Test Intonation

VERY ROUGH AND PRELIMINARY DRAFT!!! Shifting Exercises with Double Stops to Test Intonation These exercises were inspired by lessons I had from 1968 to 1970 with David Smiley of the San Francisco Symphony. I don’t have the book he used, but I believe it was one those written by Dounis on the scientific or artist's technique of violin playing. The exercises were difficult and frustrating, and involved shifting and double stops. Smiley also emphasized routine testing notes against other strings, and I also found some of his tasks frustrating because I couldn’t hear intervals that apparently seemed so familiar to a professional musician. When I found myself giving violin lessons in 2011, I had a mathematical understanding of why it was so difficult to hear certain musical intervals, and decided not to focus on them in my teaching. By then I had also developed some exercises to develop my own intonation. These exercises focus entirely on what is called the just scale. Pianos use the equal tempered scale, which is the predominate choice of intonation in orchestras and symphonies (I NEED VERIFICATION THAT THIS IS TRUE). It takes many years and many types of exercises and activities to become a good violinist. But I contend that everyone should start by mastering the following double stops in “just” intonation: 1. Practice the intervals shown above for all possible pairs of strings on your violin or viola. Learn the first two first, then add one interval at a time. They get harder to hear as you go down the list for reasons having to do with the fractions: 1/2, 2/3, 3/4, 3/5, 4/5, 5/6. -

Introduction to GNU Octave

Introduction to GNU Octave Hubert Selhofer, revised by Marcel Oliver updated to current Octave version by Thomas L. Scofield 2008/08/16 line 1 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 -0.2 -0.4 8 6 4 2 -8 -6 0 -4 -2 -2 0 -4 2 4 -6 6 8 -8 Contents 1 Basics 2 1.1 What is Octave? ........................... 2 1.2 Help! . 2 1.3 Input conventions . 3 1.4 Variables and standard operations . 3 2 Vector and matrix operations 4 2.1 Vectors . 4 2.2 Matrices . 4 1 2.3 Basic matrix arithmetic . 5 2.4 Element-wise operations . 5 2.5 Indexing and slicing . 6 2.6 Solving linear systems of equations . 7 2.7 Inverses, decompositions, eigenvalues . 7 2.8 Testing for zero elements . 8 3 Control structures 8 3.1 Functions . 8 3.2 Global variables . 9 3.3 Loops . 9 3.4 Branching . 9 3.5 Functions of functions . 10 3.6 Efficiency considerations . 10 3.7 Input and output . 11 4 Graphics 11 4.1 2D graphics . 11 4.2 3D graphics: . 12 4.3 Commands for 2D and 3D graphics . 13 5 Exercises 13 5.1 Linear algebra . 13 5.2 Timing . 14 5.3 Stability functions of BDF-integrators . 14 5.4 3D plot . 15 5.5 Hilbert matrix . 15 5.6 Least square fit of a straight line . 16 5.7 Trapezoidal rule . 16 1 Basics 1.1 What is Octave? Octave is an interactive programming language specifically suited for vectoriz- able numerical calculations. -

Major and Minor Scales Half and Whole Steps

Dr. Barbara Murphy University of Tennessee School of Music MAJOR AND MINOR SCALES HALF AND WHOLE STEPS: half-step - two keys (and therefore notes/pitches) that are adjacent on the piano keyboard whole-step - two keys (and therefore notes/pitches) that have another key in between chromatic half-step -- a half step written as two of the same note with different accidentals (e.g., F-F#) diatonic half-step -- a half step that uses two different note names (e.g., F#-G) chromatic half step diatonic half step SCALES: A scale is a stepwise arrangement of notes/pitches contained within an octave. Major and minor scales contain seven notes or scale degrees. A scale degree is designated by an Arabic numeral with a cap (^) which indicate the position of the note within the scale. Each scale degree has a name and solfege syllable: SCALE DEGREE NAME SOLFEGE 1 tonic do 2 supertonic re 3 mediant mi 4 subdominant fa 5 dominant sol 6 submediant la 7 leading tone ti MAJOR SCALES: A major scale is a scale that has half steps (H) between scale degrees 3-4 and 7-8 and whole steps between all other pairs of notes. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 W W H W W W H TETRACHORDS: A tetrachord is a group of four notes in a scale. There are two tetrachords in the major scale, each with the same order half- and whole-steps (W-W-H). Therefore, a tetrachord consisting of W-W-H can be the top tetrachord or the bottom tetrachord of a major scale. -

Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteenth Chords Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteen Chords Sometimes Referred to As Chords with 'Extensions', I.E

Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteenth chords Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteen chords sometimes referred to as chords with 'extensions', i.e. extending the seventh chord to include tones that are stacking the interval of a third above the basic chord tones. These chords with upper extensions occur mostly on the V chord. The ninth chord is sometimes viewed as superimposing the vii7 chord on top of the V7 chord. The combination of the two chord creates a ninth chord. In major keys the ninth of the dominant ninth chord is a whole step above the root (plus octaves) w w w w w & c w w w C major: V7 vii7 V9 G7 Bm7b5 G9 ? c ∑ ∑ ∑ In the minor keys the ninth of the dominant ninth chord is a half step above the root (plus octaves). In chord symbols it is referred to as a b9, i.e. E7b9. The 'flat' terminology is use to indicate that the ninth is lowered compared to the major key version of the dominant ninth chord. Note that in many keys, the ninth is not literally a flatted note but might be a natural. 4 w w w & #w #w #w A minor: V7 vii7 V9 E7 G#dim7 E7b9 ? ∑ ∑ ∑ The dominant ninth usually resolves to I and the ninth often resolves down in parallel motion with the seventh of the chord. 7 ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ & ˙ ˙ #˙ ˙ C major: V9 I A minor: V9 i G9 C E7b9 Am ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ ? ˙ ˙ The dominant ninth chord is often used in a II-V-I chord progression where the II chord˙ and the I chord are both seventh chords and the V chord is a incomplete ninth with the fifth omitted. -

When the Leading Tone Doesn't Lead: Musical Qualia in Context

When the Leading Tone Doesn't Lead: Musical Qualia in Context Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Claire Arthur, B.Mus., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: David Huron, Advisor David Clampitt Anna Gawboy c Copyright by Claire Arthur 2016 Abstract An empirical investigation is made of musical qualia in context. Specifically, scale-degree qualia are evaluated in relation to a local harmonic context, and rhythm qualia are evaluated in relation to a metrical context. After reviewing some of the philosophical background on qualia, and briefly reviewing some theories of musical qualia, three studies are presented. The first builds on Huron's (2006) theory of statistical or implicit learning and melodic probability as significant contributors to musical qualia. Prior statistical models of melodic expectation have focused on the distribution of pitches in melodies, or on their first-order likelihoods as predictors of melodic continuation. Since most Western music is non-monophonic, this first study investigates whether melodic probabilities are altered when the underlying harmonic accompaniment is taken into consideration. This project was carried out by building and analyzing a corpus of classical music containing harmonic analyses. Analysis of the data found that harmony was a significant predictor of scale-degree continuation. In addition, two experiments were carried out to test the perceptual effects of context on musical qualia. In the first experiment participants rated the perceived qualia of individual scale-degrees following various common four-chord progressions that each ended with a different harmony.