Summary Report – Citizens' Perspectives on Poverty in Edinburgh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Groups & Programmes for Parents and Carers

Programmes, Activities and Groups for parents and carers in North West Edinburgh Western Edinburgh including Blackhall, Carrick Knowe, Cramond, Clermiston, Corstorphine, Davidson’s Mains, Drumbrae, East Craigs, Gyle, Murrayfield, Roseburn February 2017 Contents Page Childcare for eligible two year olds 3 Parenting Programmes Peep 4-5 Psychology of Parenting Programme (PoPP) 6-7 The Incredible Years / Triple P Raising Children with Confidence 8 Raising Teens with Confidence 8 Teen Triple P 9 Nursery & Early Years Hub Groups for Parents/Carers 10 General Groups for Parents/Carers 11 Information and Support Sessions for Parents/Carers 13-14 Adult and Child Activities 15-18 Support and Advice Groups and Activities 19-22 Support and Advice Organisations 21-23 Playgroups 24 Community Centres / Early Years Centres and Hubs / Medical Centres 25 Notes 26-27 Contacts 28 2 Early learning and childcare for eligible two year olds Certain children are entitled to receive up to 600 hours of free early learning and childcare during school terms. For a list of establishments offering this service, to find out if your two year old qualifies for a place, and to apply please go to: www.edinburgh.gov.uk/info/20071/nurseries_and_childcare/1118/ early_learning_and_childcare_for_two_year_olds Fox Covert Early Years Centre and Nursery Class In the grounds of the Fox Covert Primary schools Clerwood Terrace, EH12 8PG Contact Janie Jones 339 3749 [email protected] New Gylemuir Early Years Hub In the grounds of Gylemuir Primary School, Wester Broom Place Contact Alison Thomson 334 7138 Hillwood Early Years Hub In the grounds of Hillwood Primary School, Ratho Station Contact Jackie Macnab 331 3594 3 Parenting Programmes Peep Learning Together Programme Sessions support parents and carers of children 0-5yrs to value and build on the home learning environment and relationships with their children, by making the most of everyday learning opportunities - listening, talking, playing, singing and sharing books and stories together. -

List of Public Roads R to Z

Edinburgh Roads Adoption Information as @ 1st September 2021 Name Locality Street Adoption Status Property Notice Description RACKSTRAW PLACEFrom Moffat Way north to junction of Harewood Road & Murchie Rackstraw Place Niddrie Adopted Crescent. Carriageway and adjacent footways are adopted for maintenance Radical Road Holyrood Private RADICAL ROADPRIVATE ROAD: HOLYROOD PARK. RAEBURN MEWSPRIVATE MEWS: north and eastwards off RAEBURN PLACE serving the Raeburn Mews Stockbridge Private development of new houses.Not adopted for maintenance under the List of Public Roads. RAEBURN PLACEFrom DEAN STREET centre ‐line westwards to PORTGOWER PLACE. Raeburn Place Stockbridge Adopted Carriageways and adjacent footways adopted for maintenance. RAEBURN STREETFrom RAEBURN PLA CE south‐eastwards to DEAN STREET. Carriageways Raeburn Street Stockbridge Adopted and adjacent footways adopted for maintenance. RAE'S COURTStreet split between PUBLIC & PRIVATE sections.PUBLIC SECTION: From St Katharine's Crescent south‐west for approximately 11.5 m or thereby. Including adjacent asphalt footways. Carriageway & adjacent footways are adopted for maintenance.PRIVATE SECTION: From public section south‐westwards ‐a cul‐de‐sac.Not included for maintenance Rae's Court Gracemount Private under the List of Public Roads. Railpath ‐ Lower Granton Road to RAILPATH ‐ LOWER GRANTON ROAD TO GRANTON PROMENADEFrom TRINITY CRESCENT Granton Promenade Granton Adopted eastwards to LOWER GRANTON ROAD.Footway adopted for maintenance. RAITH GAITPROSPECTIVELY ADOPTABLE:Under construction. Not as yet included for Raith Gait Greendykes Prospectively Adopted maintenance under the List of Public Roads. RAMAGE SQUAREPROSPECTIVELY ADOPTABLE: Under construction. From Victoria Quay south, east & then north torejoin Victoria Quay. Not as yet adopted for maintenance under Ramage Square North Leith Prospectively Adopted the List of PublicRoads. -

Applicant Data

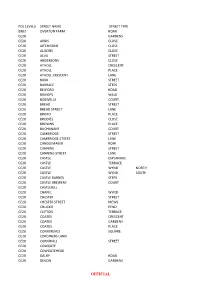

POL LEVEL5 STREET NAME STREET TYPE BX02 OVERTON FARM ROAD CE20 GARDENS CE20 AIRDS CLOSE CE20 AITCHISONS CLOSE CE20 ALISONS CLOSE CE20 ALVA STREET CE20 ANDERSONS CLOSE CE20 ATHOLL CRESCENT CE20 ATHOLL PLACE CE20 ATHOLL CRESCENT LANE CE20 BANK STREET CE20 BARRACE STEPS CE20 BELFORD ROAD CE20 BISHOPS WALK CE20 BOSWELLS COURT CE20 BREAD STREET CE20 BREAD STREET LANE CE20 BRISTO PLACE CE20 BRODIES CLOSE CE20 BROWNS PLACE CE20 BUCHANANS COURT CE20 CAMBRIDGE STREET CE20 CAMBRIDGE STREET LANE CE20 CANDLEMAKER ROW CE20 CANNING STREET CE20 CANNING STREET LANE CE20 CASTLE ESPLANADE CE20 CASTLE TERRACE CE20 CASTLE WYND NORTH CE20 CASTLE WYND SOUTH CE20 CASTLE BARNES STEPS CE20 CASTLE BREWERY COURT CE20 CASTLEHILL CE20 CHAPEL WYND CE20 CHESTER STREET CE20 CHESTER STREET MEWS CE20 CHUCKIE PEND CE20 CLIFTON TERRACE CE20 COATES CRESCENT CE20 COATES GARDENS CE20 COATES PLACE CE20 CONFERENCE SQUARE CE20 CORDINERS LAND CE20 CORNWALL STREET CE20 COWGATE CE20 COWGATEHEAD CE20 DALRY ROAD CE20 DEVON GARDENS OFFICIAL CE20 DEVON PLACE CE20 DEWAR PLACE CE20 DEWAR PLACE LANE CE20 DOUGLAS CRESCENT CE20 DOUGLAS GARDENS CE20 DOUGLAS GARDENS MEWS CE20 DRUMSHEUGH GARDENS CE20 DRUMSHEUGH PLACE CE20 DUNBAR STREET CE20 DUNLOPS COURT CE20 EARL GREY STREET CE20 EAST FOUNTAINBRIDGE CE20 EDMONSTONES CLOSE CE20 EGLINTON CRESCENT CE20 FESTIVAL SQUARE CE20 FORREST HILL CE20 FORREST ROAD CE20 FOUNTAINBRIDGE CE20 GEORGE IV BRIDGE CE20 GILMOURS CLOSE CE20 GLADSTONES LAND CE20 GLENCAIRN CRESCENT CE20 GRANNYS GREEN STEPS CE20 GRASSMARKET CE20 GREYFRIARS PLACE CE20 GRINDLAY STREET CE20 -

CIMT 17/7/2020 – Spaces for People Project Approval Notification Sent To

CIMT 17/7/2020 – Spaces for People Project Approval Notification sent to all ward councillors, transport spokespeople, emergency services, Living Streets, Spokes, RNIB, Edinburgh Access Panel and relevant Community Councils on 7 July 2020. Recipients were given five days to respond with comments. The measures would be implemented under emergency delegated decision-making powers using a Temporary Traffic Regulation Order. Given the urgent nature of these works, normal expectations about community consultations cannot be fulfilled. Project Proposal Location Justification Recommendation Meadow Place Provide protected cycling infrastructure on a key local route to Progress with scheme as part of Road important local destinations such as shops, the tram and cycling Quiet overall emergency measures to re- Route 8. This will enable communities in this area of the city to travel designate key parts of the road safely by bike as lockdown eases. network to help pedestrians and cyclists travel safely while meeting physical distancing requirements. Feedback Comment from Comment Response Cllr Webber What consultation has been done with Through consultation on the West Edinburgh Link it residents/businesses living along this stretch and was highlighted at a number of consultation events detail of the online request that initiated this that cycleways here would be beneficial to the local community. There are also numerous calls for protected cycleways here on the Spaces for People Commonplace website. Under Covid-19 conditions it creates a viable and safe way for people to access local shops and the existing Quiet Route 8 for exercise and commuting, with maintaining social distancing. Cllr Webber The relative scoring of this project on the decision / It is ranked within the priority 1 group of schemes assessment matrix provided at P&S on 14th May for implementation under travelling safely. -

Church Flowers the Name of the Team Member Arranging the Flowers Is in Brackets

www.corstorphineoldparish.org.uk Diary Dates 8th Feb (Wed) Fabric Committee meets at 7.30pm in the Session Room 11th Feb (Sat) Men’s Breakfast Fellowship Meeting at 8. 30am in the Kirk Loan Hall 12th Feb (Sun) Sunday Service at 10.30am 10th—15th Feb (inc) Church Office closed 19th Feb (Sun) Sunday Service at 10.30am 20th Feb (Mon) Finance Committee meets at 7.30pm in the Committee Room 20th Feb (Mon) Last date for March magazine material 22nd Feb (Wed) Congregational Board meets at 7.30pm in the Session Room 26th Feb (Sun) Sunday Service at 10.30am 27th Feb (Mon) Seedling Coffee Morning in the Kirk Loan Hall at 1 0am 1st March (Wed) Joint meeting of Kirk Session and Congregational Board at 7.30pm in the Session Room 2nd March (Thur) Office Hour 7-8pm — no appointment necessary 5th March (Sun) Sacrament of Holy Communion with services at 8.30am and 10.30am 11th March (Sat) Men’s Breakfast Fellowship Meeting at 8. 30am in the Kirk Loan Hall 12th March (Sun) Service at 10.30am 19th March (Sun) Service at 10.30am followed by the Stated Annual Meeting of the Old Parish (all members of the congregation warmly invited to attend) Corstorphine Old Parish Church, Kirk Loan, Edinburgh EH12 8HD Scottish Charity number: SC016009 Sunday Worship at 10.30am - On the first Sunday of every month there is a short service of Communion at 11.30am except March, June, October and December when there are services of Holy Communion at 8.30am and 10.30am Church Office - 2A Corstorphine High Street EH12 7ST. -

CORSTORPHINE COMMUNITY COUNCIL – Submission to City of Edinburgh Council’S Retaining ‘Spaces for People’ Measure’S Consultation

vCORSTORPHINE COMMUNITY COUNCIL – Submission to City of Edinburgh Council’s Retaining ‘Spaces for People’ Measure’s consultation The Corstorphine Community Council wishes to make the following submission to the City of Edinburgh Council’s (CEC) Retaining ‘Spaces for People’ (SfP) Measure’s consultation as our residents are affected by the proposal. GENERAL COMMENTS Corstorphine CC is entirely supportive of the health and safety rationale behind SfP Measures in addressing the challenges of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. The introduction of measures around local schools has been positively commented on and are widely appreciated. Residents conflate the thematically linked but separate issues of SfP Measures, the proposed Controlled Parking Zone, and the proposed Low Traffic Neighborhoods’. Negative views on one issue colors opinions on the other two. Indeed, the views expressed by residents often illustrates their confusion. Several of the SfP Measures have only recently been introduced. An example being Corstorphine High Street. Changes require residents to have a reasonable amount of time to adjust and have a considered view of the intended benefits of the measures. By asking for views now the City Council may be inviting a jaundiced response. CORSTORPHINE RESIDENTS’ VIEWS “Gylemuir Primary School The closure at Gylemuir Primary has been helpful for families cycling to Corstorphine Primary through the Gyle Park as this is on their safer route to school.” “Carrick Knowe Primary School Having that extra space now has been great regarding social distancing and just a more pleasant route to school for families. If it continues, we would hopefully be successful in encouraging walk/bike to school choices rather than cars. -

Western NEP Report - 2Feb17 - DS.Doc

Western Edinburgh Neighbourhood Partnership 7pm, Thursday 2 February 2017 Neighbourhood Environmental Programme - 2016/17 Item number 5.3 Report number Executive/routine Wards - Ward 3 – Drum Brae/Gyle Ward 6 – Corstorphine/Murrayfield Executive summary This report provides an overview on works included in the Western Neighbourhood Environmental Programme (NEP) 2016/17. 1 Western NEP Report - 2Feb17 - DS.doc Neighbourhood Environmental Programme Report 2016-17 Recommendations The Western Neighbourhood Partnership is asked to: 1.1 Note the projects included in the 2016/17 Neighbourhood Environmental Programme (NEP) at 3.1 and 3.4 below. 1.2 Agree to progress with Phase 2 of the Clermiston Back Greens project as the HRA NEP for 2017/18, subject to further consultation with residents as detailed in 3.3 below 1.3 Note the project bank of Roads projects detailed in 3.6 below. Background 2.1 The NEP budget for 2016/17 is £85,512 for Housing Revenue Account projects and £200,000 for Roads & Footpaths projects. 2.2 £265,324 of NEP projects have been completed or have had funding committed in 2016/17, representing 93% of the available budget. Main report 3.1 The HRA NEP budget has been allocated to in full to Phase 1 of the Clermiston Back Green project which had previously been agreed by the board. This project was the subject of widespread consultation during 2015, and Phase 1 comprises significant backgreen improvements in the area bounded by Essendean Terrace, Hoseasons Gardens, Essendean Place and Alan Breck Gardens. 3.2 Estimated costs of this project are £87,000 and the project therefore requires to go through a mini-tender process, which is currently being carried out. -

The City of Edinburgh Council

Notice of meeting and agenda The City of Edinburgh Council 10.00 am, Thursday, 24 November 2016 Council Chamber, City Chambers, High Street, Edinburgh This is a public meeting and members of the public are welcome to attend Contact E-mail: [email protected] Tel: 0131 529 4246 1. Order of business 1.1 Including any notices of motion and any other items of business submitted as urgent for consideration at the meeting. 2. Declaration of interests 2.1 Members should declare any financial and non-financial interests they have in the items of business for consideration, identifying the relevant agenda item and the nature of their interest. 3. Deputations 3.1 If any 4. Minutes 4.1 The City of Edinburgh Council of 27 October 2016 (circulated) – submitted for approval as a correct record 5. Questions 5.1 By Councillor Rose – Freedom of Information – for answer by the Leader of the Council 5.2 By Councillor Mowat – Building Warrants – for answer by the Convener of the Planning Committee 5.3 By Councillor Rust – Christmas Lighting – for answer by the Convener of the Culture and Sport Committee 5.4 By Councillor Whyte – Homelessness – for answer by the Convener of the Health, Social Care and Housing Committee 5.5 By Councillor Rose – Accuracy of Statements Alleging Hate Crime – for answer by the Convener of the Communities and Neighbourhoods Committee 5.6 By Councillor Aitken – for answer by the Convener of the Transport and Environment Committee 5.7 By Councillor Rose – Clarification of Declared Ownership of India Buildings – for answer by the Deputy Leader of the Council 5.8 By Councillor Mowat – New Town Celebrations – for answer by the Convener of the Culture and Sport Committee 5.9 By Councillor Nick Cook – Road Defects – for answer by the Convener of the Transport and Environment Committee The City of Edinburgh Council – 24 November 2016 Page 2 of 7 5.10 By Councillor Booth – Sweeping of Leaves from Footpaths and Cyclepaths – for answer by the Convener of the Transport and Environment Committee 6. -

Groups Flyer Sept Oct 2016

3-6 year old behaviour Rosebery Hall 17 West Terrace, South Queensferry EH30 9LL Wednesday 26/10/2016 12.30 – 2.30 pm We have free courses for parents and carers of 3-6 year olds that can help you. Royston/Wardieburn Community Centre 11, Pilton Dr N, Edinburgh EH5 1NF Thursday 27/10/2016 12.30 – 2.30 pm Incredible Years Dalry Primary School 4 Cathcart Place Edinburgh EH11 2JB Viewforth Early Years Centre Thursday 27th October 2016 9.15am -11.15am (Evening course) 18-22 Viewforth Terrace, Edinburgh EH10 4LH Circle Haven/ Craigroyston Primary School Wednesday 26/10/2016 6 – 8 pm Muirhouse Place WestEdinburgh EH4 4PX Thursday 1/9/2016 9.00 – 11.30am Gilmerton Community Centre 4 Drum St, Edinburgh EH17 8QG Westerhailes Education centre Wednesday 7/9/2016 9.30 - 11.30 am 9 Murrayburn Drive Edinburgh EH14 2SU Friday 2nd September 2016 9.15 am – 11.15 am Moffat Early Years Campus 30 Wauchope Terrace, Edinburgh EH16 4NU Friday 28/10/2016 9.15 – 11.15 am Triple P Brunstane Primary School Goodtrees Neighbourhood Centre 106 Magdalene Drive, Edinburgh EH15 3BO 5 Moredunvale Place, Edinburgh EH17 7LB Thursday 27/10/2016 9.15 - 11.15 am (Dads group) Wednesday 14/9/2016 12.30 – 2.30 pm Gylemuir Primary School (School Ages 7 to 11yrs) Wester Broom Place, Edinburgh EH12 7RT Thursday 15/9/2016 9.30 – 11.30 am Tuesday 20/9/2016 9.15 – 11.15 am Dr Bell’s Family Centre Fox Covert Early Years Centre 15 Junction Pl, Edinburgh EH6 5JA 12 Clerwood Terrace, Edinburgh EH12 8PG Tuesday 25/10/2016 9.15 – 11.15 am Wednesday 26/10/2016 9.15 - 11.15 am Gate 55 55 Sighthill Road. -

Street Arboretum Place Ardmillan Place Argyle Crescent Arrol Place

Street Arboretum Place Ardmillan Place Argyle Crescent Arrol Place Assembly Street Bangor Road Bankhead Crossway North Bankhead Grove Bankhead Medway Blackford Road Boswall Quadrant Boswall Terrace Braid Road Broad Wynd Broomhills Road Broomhouse Avenue Broomhouse Bank Broomhouse Court Broomhouse Crescent Broomhouse Grove Broomhouse Loan Broomhouse Park Broomhouse Place North Broomhouse Place South Broomhouse Road Broomhouse Row Broomhouse Street North Broomhouse Street South Broomhouse Terrace Broomhouse Walk Broughton Road Bryson Road Burlington Street Cables Wynd Calder Crescent Calder Drive Calder Gardens Calder Grove Calder Park Calder Place Calder Road Calder Road -sr 187-385 Calder Road Sr 387-495 Calder Road Sr Nos 298-370 Calton Hill Canon Street Carpet Lane Carrington Road Carron Place Clermiston Road Clermiston Road North Colinton Mains Crescent Colinton Mains Drive Colinton Mains Green Colinton Mains Grove Colinton Mains Place Colinton Mains Road Colinton Mains Terrace Comely Bank Avenue Comely Bank Grove Corunna Place Craigcrook Road Craighall Road Craigmillar Castle Avenue Craigmillar Castle Gardens Craigmillar Castle Road Dalkeith Road Dalry Road Dean Park Street Downfield Place Drum Brae Drive Dudley Crescent Duff Street Dumbryden Road Dundas Avenue Dundee Terrace East Fettes Avenue Easter Drylaw Avenue Easter Drylaw Bank Easter Drylaw Drive Easter Drylaw Gardens Easter Drylaw Grove Easter Drylaw Loan Ellersley Road Ferniehill Gardens Ferniehill Place Ferniehill Street Fettes Avenue Ford's Road Fowler Terrace Gillsland -

Attitudes Toward Poverty in Edinburgh 1

Attitudes toward poverty in Edinburgh 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents ......................................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................... 4 Main Messages ............................................................................................................................. 5 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 12 2. Our Approach ......................................................................................................................... 13 2.1 – Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 13 2.2 – Survey Design ................................................................................................................................. 13 2.3 – Ethics .............................................................................................................................................. 14 2.4 – Survey Distribution ......................................................................................................................... 15 2.5 – Appraising the Survey Population .................................................................................................. 16 2.6 – Data Cleaning ................................................................................................................................ -

Transport and Environment Committee

Transport and Environment Committee 2.30pm, Tuesday, 5 March 2019 Strategic Review of Parking – Results of Area 1 Review and Corstorphine Consultation Results Item number 7.5 Report number Executive/routine Executive Wards 1, 3, 6 Council Commitments Executive Summary At its meeting of 9 August 2018 Committee considered a report on a proposed strategic review of parking across the Edinburgh area. That report explained that it was proposed to conduct an initial investigation into the severity and extent of parking pressures, splitting the city into five separate, geographical areas with the aim of assessing the potential need for parking controls. The results of those investigations would be reported to future meetings of this Committee. This report provides the results of the first of those investigations, covering Area 1, West Edinburgh. This report also summarises the results of the recent consultation carried out in the Corstorphine area, where residents and businesses were asked for their views on both the existing parking situation in Corstorphine and the need for potential solutions. The report also provides and update on the anticipated timescales for delivering the results of the review in the remaining four areas, as well as providing an update on the separate piece of work being carried out in relation to event parking at Edinburgh’s three major sporting stadiums. Report Strategic Review of Parking – Results of Area 1 Review and Corstorphine Consultation Results 1. Recommendations 1.1 It is recommended that the Committee: 1.1.1