The History of Derbyshire Pages 1 to 40

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Derbyshire T-Government Management Board

10. DERBYSHIRE T-GOVERNMENT MANAGEMENT BOARD 1. TERMS OF REFERENCE (i) Developing policy and priority Issues in the approach to developing e-government for Derbyshire (ii) To agree the allocation of the ODPM Government on –line grant (iii) To agree the engagement of consultants, staff secondments and use of resources for developmental work on core e- government projects (iv) To agree standards and protocols for joint working and information sharing between authorities. (v) Consider and agree option appraisals and business solutions that will meet common goals. (vi) Recommend and agree procurement arrangements (vii) Determine, where appropriate, lead authority arrangements (viii) Consider any budget provision that individual authorities may need to contribute towards the costs or resource needs of the partnership (ix) Consult the Derbyshire e-government partnership forum on progress (x) To nominate as appropriate representatives of the Board to steer the development of individual E-Government projects (xi) To consider and pursue additional resource funding from Government, EU or other sources and any match funding implications 2. MEMBERSHIP One member together with the Head of Paid Service or Chief Executive from each of the following constituent authorities:- Derbyshire County Council (Lead Authority), Derby City Council, North East Derbyshire District Council, the District of Bolsover, Chesterfield Borough Council, Amber Valley District Council, Erewash Borough Council, South Derbyshire District Council, Derbyshire Dales District Council, High Peak Borough Council, Derbyshire Police Authority, Derbyshire Fire Authority 4/10/1 Named substitutes for any of the above The Peak District National Park Authority be provided with a watching brief 2. FINANCE The Board shall operate under the Financial Regulations and Contract Standing Orders of Derbyshire Council the Lead Authority. -

Dovedale Primary Admission Arrangements 2019-2020

Willows Academy Trust Published Admissions Criteria Aiming HighTogether Dovedale Primary School Dovedale Primary School is part of Willows Academy Trust. As an academy, we are required to set and publish our own admissions criteria. Admission applications are managed through the Derbyshire Co-ordinated Admissions Scheme and are in line with the Derbyshire Admission arrangements for community and voluntary controlled schools. Individual pupils who have a statement of special educational needs which names Dovedale Primary School will be admitted. In deciding on admissions to Dovedale Primary School, the following order of priority will be adopted. 1. Looked after children and children who were looked after but ceased to be so because they were adopted (or became subject to a residence order or special guardianship order). 2. Children living in the normal area served by the school at the time of application and admission who have brothers or sisters attending the school at the time of application and admission. 3. Children living in the normal area served by the school at the time of application and admission. 4. Children not living in the normal area served by the school but who have brothers or sisters attending the school at the time of application and admission. 5. Other children whose parents have requested a place. Where, in the case of 2, 3, 4 or 5 above, choices have to be made between children satisfying the same criteria, those children living nearest to the school will be given preference. We reserve the right to withdraw any offer of a school place which has been obtained as a result of misleading or fraudulent information. -

DERBYSHIRE. GBO 487 Kay Andrew,Riddings, Alfreton ::\Farshall G

TB.ADIS )IBEOTOBY ,) DERBYSHIRE. GBO 487 Kay Andrew,Riddings, Alfreton ::\farshall G. N ewhall, Burton-on-Trent IPearson G ;orge, Bugsworth, Stockport Kay William,Biackbrook, Bel per :Marshall Thomas, Dore, Sheffield Pearson John W. Staveley, Che'iterfield Keeling S. 19 hanby st. Ilkeston R.S.O }lartin Chas. Jn. Brimington, Chesterf!d Pearson Thos. Fenny Bentley, Ashborne Kelk \\'m . .Ma'ket pl. J\'Ielbourne, Derby Martin Timothy, Post office, ~ hatstand- Peat :Mrs. Constance, Duftield, Derby Kemp Matthov, Heage, Belper well, Derby Peat V.J.Market st.Eckington,Chestrfid Kennedy Tho. 87 Kedleston rd. Derby :Mason Chas. 2 Packers row, Chesterfield Peat '"'illiam, 292 Abbey street, Derby Ken sit Henry Thomas, C'odnor, Derby }lason Mrs. E. 23 Stanhope st. Derby Peat man Jas. B<trron hill, Chesterfield Kent Mrs. Ma-y Ann, Duffield, Derby }lason :NI.W.rs8 Bath st.llkeston R.S.O Pedley Wm. H. 78 Princess st. Glossop Kerry John, lerby road, Heanor R.S.O Massey W. Oakthorpe, Ashby-dc-la-Zch Peel Arth.64 Station rd. Ilkeston R.S.O Key l\Irs. Maw, Wessington, Alfreton l\laxfield Thomas, Cotton street, Bols- Peel Roger, Stavcley, ChesterfiE'ld Kidd David, Cromford, Derby uver, Chesterfield Peel William,Langlcyl\'lillR.S.O.(Notts) ~!ddy ~iss, Eizh. Lo~g row\Belper i\Iayfield Fredk. 11 Junction ~t. DerJ:>y 1 Peggs Charles, Pear Tree road, Der~Y. Kmder Georg~ 198 H1gh st. Glossop tMelbourne John & Sons, GreenwiCh, Pendleton l\lrs. l\Iary .A. Brushes, Whlt- Kinder Miss il'argaret Susan, Two dales, Ripley, Derby tington, Chesterfield Darley, Matock t.Mellor T. -

Michelle Smith Eversheds LLP Bridgewater

Michelle Smith Our Ref: APP/R1010/A/14/2212093 Eversheds LLP Bridgewater Place Water Lane LEEDS LS11 5DR 12 March 2015 Dear Madam TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT 1990 (SECTION 78) APPEAL BY ROSELAND COMMUNITY WINDFARM LLP: LAND EAST OF ROTHERHAM ROAD, BOLSOVER, DERBYSHIRE APPLICATION REF: 12/00159/FULEA 1. I am directed by the Secretary of State to say that consideration has been given to the report of the Inspector, Paul K Jackson BArch (Hons) RIBA, who held a public local inquiry which opened on 4 November 2014 into your client’s appeal against the decision of Bolsover District Council (the Council) to refuse planning permission for a windfarm comprising 6 wind turbines, control building, anemometer mast and associated access tracks on a site approximately 2.5km south of Bolsover between the villages of Palterton and Shirebrook, in accordance with application reference 12/00159/FULEA, dated 25 April 2012. 2. On 20 June 2014 the appeal was recovered for the Secretary of State's determination, in pursuance of section 79 of and paragraph 3 of Schedule 6 to the Town and Country Planning Act 1990, because it involves a renewable energy development. Inspector’s recommendation and summary of the decision 3. The Inspector recommended that the appeal be dismissed and planning permission refused. For the reasons given below, the Secretary of State agrees with the Inspector’s conclusions except where indicated otherwise, and agrees with his recommendation. A copy of the Inspector’s report (IR) is enclosed. All references to paragraph numbers, unless otherwise stated, are to that report. -

School Administrator South Wingfield Primary School Church Lane South Wingfield Alfreton Derbyshire DE55 7NJ

School Administrator South Wingfield Primary School Church Lane South Wingfield Alfreton Derbyshire DE55 7NJ School Administrator Newhall Green High School Brailsford Primary School Da Vinci Community College Newall Green High School Main Road St Andrew's View Greenbrow Road Brailsford Ashbourne Breadsall Manchester Derbys Derby Greater Manchester DE6 3DA DE21 4ET M23 2SX School Administrator School Administrator School Administrator Tower View Primary School Little Eaton Primary School Ockbrook School Vancouver Drive Alfreton Road The Settlement Winshill Little Eaton Ockbrook Burton On Trent Derby Derby DE15 0EZ DE21 5AB Derbyshire DE72 3RJ Meadow Lane Infant School Fritchley Under 5's Playgroup Jesse Gray Primary School Meadow Lane The Chapel Hall Musters Road Chilwell Chapel Street West Bridgford Nottinghamshire Fritchley Belper Nottingham NG9 5AA DE56 2FR Nottinghamshire NG2 7DD South East Derbyshire College School Administrator Field Road Oakwood Junior School Ilkeston Holbrook Road Derbyshire Alvaston DE7 5RS Derby Derbyshire DE24 0DD School Secretary School Secretary Leaps and Bounds Day Nursery Holmefields Primary School Ashcroft Primary School Wellington Court Parkway Deepdale Lane Belper Chellaston Sinfin Derbyshire Derby Derby DE56 1UP DE73 1NY Derbyshire DE24 3HF School Administrator Derby Grammar School School Administrator All Saints C of E Primary School Derby Grammar School Wirksworth Infant School Tatenhill Lane Rykneld Road Harrison Drive Rangemore Littleover Wirksworth Burton on Trent Derby Matlock Staffordshire Derbyshire -

Conservation Area

Netherseal Conservation Area Character Statement 2011 SOUTH DERBYSHIRE DISTRICT COUNCIL Netherseal Conservation Statement Character Area NethersealConservation Area Contents Introduction 1 Summary 1 Area of Archaeological Potential 2 Conservation Area Analysis 3 • Historic Development 3 • Approaches 7 • Views 8 • Spaces 9 • Building Materials and Details 10 Conservation Area Description 14 Proposed Extension to the Conservation Area 20 Loss and Damage 23 Conservation Area Map Appendix 1 Distinctive architectural details Appendix 2 Netherseal Conservation Area: Phases of Designation NethersealConservation Area Introduction This statement has been produced by Mel Morris Conservation for, and in association with, South Derbyshire District Council. It sets out the special historic and architectural interest that makes the character and appearance of Netherseal worthy of protection. It also assesses the degree of damage to that special interest and thus opportunities for future enhancement. This document will be used by the Council when making professional judgements on the merits of development applications. The Netherseal Conservation Area was designated by South Derbyshire District Council on 13th July 1978, and was extended by South Derbyshire District Council on 9th June 2011. Summary Netherseal lies in the extreme south of the County of Derbyshire. The edge of the parish, and of the village, is marked by the River Mease, which snakes along its southern perimeter. This also marks the County boundary with Leicestershire. The village did at one time belong within Leicestershire and was only drawn into Derbyshire in 1897. The area is characterised largely by rolling lowland, becoming almost flat around the River Mease. The Netherseal Conservation Statement Character Area soils in Netherseal are generally rich clays, but free draining and shallow upon the sandstone bedrock, with large areas of alluvium and river terrace deposits trailing the river valley. -

Electoral Changes) Order 1999

451659100101-10-99 11:15:59 Pag Table: STATIN PPSysB Unit: pag1 STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 1999 No. 2691 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The District of Bolsover (Electoral Changes) Order 1999 Made ---- 27th September 1999 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) Whereas the Local Government Commission for England, acting pursuant to section 15(4) of the Local Government Act 1992(a), has submitted to the Secretary of State a report dated November 1998 on its review of the district of Bolsover together with its recommendations: And whereas the Secretary of State has decided to give effect to those recommendations: Now, therefore, the Secretary of State, in exercise of the powers conferred on him by sections 17(b) and 26 of the Local Government Act 1992, and of all other powers enabling him in that behalf, hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and interpretation 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the District of Bolsover (Electoral Changes) Order 1999. (2) This Order shall come into force— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to any election to be held on 1st May 2003, on 10th October 2002; (b) for all other purposes, on 1st May 2003. (3) In this Order— “district” means the district of Bolsover; “existing”, in relation to a ward, means the ward as it exists on the date this Order is made; any reference to the map is a reference to the map prepared by the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions marked “Map of the District of Bolsover (Electoral Changes) Order 1999”, and deposited in accordance with regulation 27 of the Local Government Changes for England Regulations 1994(c); and any reference to a numbered sheet is a reference to the sheet of the map which bears that number. -

Inspection Report Netherseal St Peter's

INSPECTION REPORT NETHERSEAL ST PETER’S CHURCH OF ENGLAND (CONTROLLED) PRIMARY SCHOOL Swadlincote LEA area: Derbyshire Unique reference number: 112844 Acting Headteacher: Mrs C Braund Reporting inspector: Mr C Smith 25211 Dates of inspection: 9th – 11th June 2003 Inspection number: 247280 Inspection carried out under section 10 of the School Inspections Act 1996 INFORMATION ABOUT THE SCHOOL Type of school: Infant and Junior School School category: Voluntary Controlled Age range of pupils: 5 to 11 years Gender of pupils: Mixed School address: Netherseal Swadlincote Derbyshire Postcode: DE12 8BZ Telephone number: 01283 760283 Fax number: 01283 763947 Appropriate authority: The Governing Body Name of chair of governors: Mr R Brunt Date of previous inspection: July 2001 © Crown copyright 2003 This report may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial educational purposes, provided that all extracts quoted are reproduced verbatim without adaptation and on condition that the source and date thereof are stated. Further copies of this report are obtainable from the school. Under the School Inspections Act 1996, the school must provide a copy of this report and/or its summary free of charge to certain categories of people. A charge not exceeding the full cost of reproduction may be made for any other copies supplied. Netherseal St Peter’s Church of England (Controlled) Primary School - ii INFORMATION ABOUT THE INSPECTION TEAM Team members Subject responsibilities Aspect responsibilities 25211 Colin Smith Registered Mathematics The characteristics -

Town and Country Planning (Local Planning) (England) Regulations 2012 Reg12

Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004 Town and Country Planning (Local Planning) (England) Regulations 2012 Reg12 Statement of Consultation SUCCESSFUL PLACES: A GUIDE TO SUSTAINABLE LAYOUT AND DESIGN SUPPLEMENTARY PLANNING DOCUMENT Undertaken by Chesterfield Borough Council also on behalf and in conjunction with: July 2013 1 Contents 1. Introduction Background to the Project About Successful Places What is consultation statement? The Project Group 2. Initial Consultation on the Scope of the Draft SPD Who was consulted and how? Key issues raised and how they were addressed 3. Peer Review Workshop What did we do? Who was involved? What were the outcomes? 4. Internal Consultations What did we do and what were the outcomes? 5. Strategic Environmental Assessment and Habitats Regulation Assessment What is a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) Is a SEA required? What is a Habitats Regulation Assessment (HRA) Is a HRA required? Who was consulted? 6. Formal consultation on the draft SPD Who did we consult? How did we consult? What happened next? Appendices Appendix 1: Press Notice Appendix 2: List of Consultees Appendix 3: Table Detailed Comments and Responses Appendix 4: Questionnaire Appendix 5: Public Consultation Feedback Charts 2 1. Introduction Background to the Project The project was originally conceived in 2006 with the aim of developing new planning guidance on residential design that would support the local plan design policies of the participating Council’s. Bolsover District Council, Chesterfield Borough Council and North East Derbyshire District Council shared an Urban Design Officer in a joint role, to provide design expertise to each local authority and who was assigned to take the project forward. -

SDL EM Apr19 Lots V2.Indd

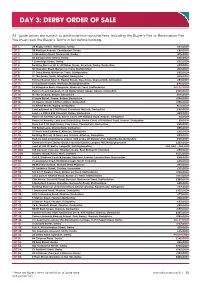

DAY 3: DERBY ORDER OF SALE All *guide prices are subject to additional non-optional fees, including the Buyer’s Fee or Reservation Fee. You must read the Buyer’s Terms in full before bidding. LOT 1. 28 Rugby Street, Wilmorton, Derby £45,000+ LOT 2. 39 Madison Avenue, Chaddesden, Derby £69,000+ LOT 3. 14 Brompton Road, Mackworth, Derby £75,000+ LOT 4. 85 Co-operative Street, Derby £50,000+ LOT 5. 1 Cummings Street, Derby £55,000+ LOT 6. Building Plot r-o 141 & 143 Baker Street, Alvaston, Derby, Derbyshire £55,000+ LOT 7. 121 Branston Road, Burton on Trent, Staffordshire £35,000+ LOT 8. 27 Duke Street, Burton on Trent, Staffordshire £65,000+ LOT 9. 15 The Green, North Wingfield, Derbyshire £35,000+ LOT 10. Former Baptist Church, Market Street, Clay Cross, Chesterfield, Derbyshire £55,000+ LOT 11. 51 Gladstone Street, Worksop, Nottinghamshire £40,000+ LOT 12. 24 Kidsgrove Bank, Kidsgrove, Stoke on Trent, Staffordshire SOLD PRIOR LOT 13. Parcel of Land between 27-35 Ripley Road, Heage, Belper, Derbyshire £150,000+ LOT 14. 15 The Orchard, Belper, Derbyshire £110,000+ LOT 15. 6 Eagle Street, Heage, Belper, Derbyshire £155,000+ LOT 16. 47 Heanor Road, Codnor, Ripley, Derbyshire £185,000+ LOT 17. 10 Alfred Street, Ripley, Derbyshire £115,000+ LOT 18. Land adjacent to 2 Mill Road, Cromford, Matlock, Derbyshire £40,000+ LOT 19. Land r-o 230 & 232 Peasehill, Ripley, Derbyshire £23,000+ LOT 20. Parcel of Amenity Land, Raven Court, Off Midland Road, Heanor, Derbyshire £8,000+ LOT 21. Parcel of Amenity Land and Outbuilding, Raven Court, off Midland Road, Heanor, Derbyshire £8,000+ LOT 22. -

Main Header 1

SHARE City Visit Exchange Programme Czech Delegation Visit Programme Wednesday 12 June Welcome dinner at the Mosborough Hall Hotel Meet in the hotel lobby at 19.45, for dinner at 8pm DAY 1: Thursday 13 June Morning programme hosted by Sheffield City Council Howden House, 1 Union Street, Sheffield S1 2SH 9.30-9.45 Arrival & Coffee 9.45-10.00 Official welcome Leader of Sheffield City Council, Councillor Julie Dore 10.00-11.00 'Introducing...' Sheffield - Belinda Gallup - Sheffield City Council Asylum Team - Raph Richards - Ethnic Minority and Traveller Achievement Service - EMTAS) - Marlene Scott (Mulberry Health Clinic) 11.00-11.15 Coffee & short break 11.15-12.30 'Introducing...' the Czech Republic - Members of the visiting delegation 12.45-13.45 Lunch Millennium Gallery Café, Arundel Gate Afternoon programme hosted by SAGE Greenfingers Grimesthorpe Road, Sheffield S4 8LE 13.45-14.00 Taxi transport to Sage Greenfingers 14.00-14.30 Arrival & Introductions Diana, Louise, Tim & Khaled - SAGE 14.30-15.15 Tour of SAGE Project gardens SAGE staff 15.15-15.45 Visit to Plot 103 and meeting with SAGE clients 15.45-16.15 Taxi transport to Abbeyfield House & refreshments 16.15-17.40 Presentation & discussion: - SAGE Greenfingers & health services - Working with refugees & local communities 17.45 Taxi transport to the hotel DAY 1: Evening Programme 20.00-20.30 Welcome & drinks reception Sheffield Town Hall, Pinstone Street, Sheffield S1 2HH 20.30 Dinner Brown's Restaurant, St Paul's Parade, Sheffield S1 DAY 2: Friday 14 June Hosted by Refugee Council -

AMBER VALLEY VACANT INDUSTRIAL PREMISES SCHEDULE Address Town Specification Tenure Size, Sqft

AMBER VALLEY VACANT INDUSTRIAL PREMISES SCHEDULE Address Town Specification Tenure Size, sqft The Depot, Codnor Gate Ripley Good Leasehold 43,274 Industrial Estate Salcombe Road, Meadow Alfreton Moderate Freehold/Leasehold 37,364 Lane Industrial Estate, Alfreton Unit 1 Azalea Close, Clover Somercotes Good Leasehold 25,788 Nook Industrial Estate Unit A Azalea Close, Clover Somercotes Moderate Leasehold/Freehold 25,218 Nook Industrial Estate Block 19, Amber Business Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 25,200 Centre, Riddings Block 2 Unit 2, Amber Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 25,091 Business Centre, Riddings Unit 3 Wimsey Way, Alfreton Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 20,424 Trading Estate Block 24 Unit 3, Amber Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 18,734 Business Centre, Riddings Derby Road Marehay Moderate Freehold 17,500 Block 24 Unit 2, Amber Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 15,568 Business Centre, Riddings Unit 2A Wimsey Way, Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 15,543 Alfreton Trading Estate Block 20, Amber Business Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 14,833 Centre, Riddings Unit 2 Wimsey Way, Alfreton Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 14,543 Trading Estate Block 21, Amber Business Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 14,368 Centre, Riddings Three Industrial Units, Heage Ripley Good Leasehold 13,700 Road Industrial Estate Industrial premises with Alfreton Moderate Leasehold 13,110 offices, Nix’s Hill, Hockley Way Unit 2 Azalea Close, Clover Somercotes Good Leasehold 13,006 Nook Industrial Estate Derby Road Industrial Estate Heanor Moderate Leasehold 11,458 Block 23 Unit 2, Amber Alfreton Moderate