From Scott to Rispart, from Ivanhoe to the York Massacre of the Jews Rewriting and Translating Historical “Fact” Into Fiction in the Historical Novel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Walls but on the Rampart Underneath and the Ditch Surrounding Them

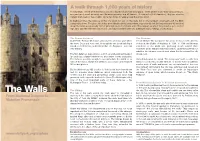

A walk through 1,900 years of history The Bar Walls of York are the finest and most complete of any town in England. There are five main “bars” (big gateways), one postern (a small gateway) one Victorian gateway, and 45 towers. At two miles (3.4 kilometres), they are also the longest town walls in the country. Allow two hours to walk around the entire circuit. In medieval times the defence of the city relied not just on the walls but on the rampart underneath and the ditch surrounding them. The ditch, which has been filled in almost everywhere, was once 60 feet (18.3m) wide and 10 feet (3m) deep! The Walls are generally 13 feet (4m) high and 6 feet (1.8m) wide. The rampart on which they stand is up to 30 feet high (9m) and 100 feet (30m) wide and conceals the earlier defences built by Romans, Vikings and Normans. The Roman defences The Normans In AD71 the Roman 9th Legion arrived at the strategic spot where It took William The Conqueror two years to move north after his the rivers Ouse and Foss met. They quickly set about building a victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. In 1068 anti-Norman sound set of defences, as the local tribe –the Brigantes – were not sentiment in the north was gathering steam around York. very friendly. However, when William marched north to quell the potential for rebellion his advance caused such alarm that he entered the city The first defences were simple: a ditch, an embankment made of unopposed. -

Understanding Clifford's Tower

1 Understanding Clifford's Tower An English Heritage & Historyworks Learning Event Supported by York City Council for Holocaust Memorial Day 2015 Report published by Historyworks giving summary of talks on Sunday 25th January The learning events that marked Holocaust Memorial Day and brought together the communities in York to "Understand Clifford's Tower" and "Understand the 1190 Massacre" were organized with support from English Heritage by Helen Weinstein, Director of Historyworks and involved over 150 participants for tours and talks on both afternoons on Sunday 25th and Tuesday 27th January 2015. To find the history summaries and illustrative materials for the York Castle Project which Helen Weinstein and the team at Historyworks have provided to share knowledge to support those wanting more information about the York Castle Area, please find many pages of chronological summaries about the site and descriptions of the interpretations offered by the stakeholders here: http://historyworks.tv/projects/ Professor Helen Weinstein, Organizer of Learning Events about the York Castle Area to mark HMD The afternoon of presentations was opened by Helen Weinstein, public historian and Director of Historyworks. Helen began by welcoming the large number of people that had returned from a walking tour of the castle area with an introduction to what the proceeding talks would offer. The event had been created as a result of a growing interest from the citizens of York and the wider Jewish communities outside of the city in Clifford’s Tower and its cultural and historical significance.Helen then spoke about some of the misconceptions about Jewish life in York, in 1 2 particular the belief that a Cherem had been placed on York following the 1190 massacre, forbidding people of Jewish faith to live within the city, particularly not to overnight or eat within the precincts of the City Walls. -

YORKSHIRE & Durham

MotivAte, eDUCAte AnD reWArD YORKSHIRE & Durham re yoUr GUests up for a challenge? this itinerary loCAtion & ACCess will put them to the test as they tear around a The main gateway to the North East is York. championship race track, hurtle down adrenaline- A X By road pumping white water and forage for survival on the north From London to York: york Moors. Approx. 3.5 hrs north/200 miles. it’s also packed with history. UnesCo World heritage sites at j By air Durham and hadrian’s Wall rub shoulders with magnifi cent Nearest international airport: stately homes like Castle howard, while medieval york is Manchester airport. Alternative airports: crammed with museums allowing your guests to unravel Leeds-Bradford, Liverpool, Newcastle airports 2,000 years of past civilisations. o By train And after all this excitement, with two glorious national parks From London-Kings Cross to York: 2 hrs. on the doorstep, there’s plenty of places to unwind and indulge while drinking in the beautiful surroundings. York Yorkshire’s National Parks Durham & Hadrian’s Wall History lives in every corner of this glorious city. Home to two outstanding National Parks, Yorkshire Set on a steep wooded promontory, around is a popular destination for lovers of the great which the River Wear curves, the medieval city of A popular destination ever since the Romans came outdoors. Durham dates back to 995 when it was chosen as to stay, it is still encircled by its medieval walls, the resting place for the remains of St Cuthbert, perfect for a leisurely stroll. -

City of York & District

City of York & District FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY INDEX TO JOURNAL VOLUME 13, 2012 INDEX TO VOLUME 13 - 2012 Key to page numbers : February No.1 p. 1 - 32 June No.2 p. 33 - 64 October No.3 p. 65 - 96 Section A: Articles Page Title Author 3 Arabella COWBURN (1792-1856) ALLEN, Anthony K. 6 A Further Foundling: Thomas HEWHEUET FURNESS, Vicky 9 West Yorkshire PRs, on-line indexes Editor 10 People of Sheriff Hutton, Index letter L from 1700 WRIGHT, Tony 13 ETTY, The Ettys and York, Part 2 ETTY, Tom 19 Searching for Sarah Jane THORPE GREENWOOD, Rosalyn 22 Stories from the Street, York Castle Museum: WHITAKER, Gwendolen 3. Charles Frederick COOKE, Scientific Instruments 25 Burials at St. Saviour RIDSDALE, Beryl 25 St. Saviourgate Unitarian Chapel burials 1794-1837 POOLE, David 31 Gleanings from Exchange Journals BAXTER, Jeanne 35 AGM March 2012:- Chairman's Report HAZEL, Phil 36/7 - Financial Statement & Report VARLEY, Mary 37 - Secretary's Report HAZEL, Phil 38 The WISE Family of East Yorkshire WISE, Tony 41 Where are You, William Stewart LAING? FEARON, Karys 46 The Few who Reached for the Sky ROOKLEDGE, Keith 47 Baedeker Bombing Raid 70 th anniversary York Press ctr Unwanted Certificates BAXTER, Jeanne 49 Thomas THOMPSON & Kit Kat STANHOPE, Peter 52 People of Sheriff Hutton, Index letter M to 1594 WRIGHT, Tony 54 ETTY, The Ettys and York, Part 3 ETTY, Tom 58 Stories from the Street, York Castle Museum: WHITAKER, Gwendolen 4. Mabel SMORFIT, Schoolchild 59 Guild of Freemen MILNER, Brenda 63 Gleanings from Exchange Journals BAXTER, Jeanne 67 The WILKINSON Family History: Part 1. -

Pedigrees of the County Families of Yorkshire

94i2 . 7401 F81p v.3 1267473 GENEALOGY COLLECTION 3 1833 00727 0389 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center http://www.archive.org/details/pedigreesofcount03fost PEDIGREES YORKSHIRE FAMILIES. PEDIGREES THE COUNTY FAMILIES YORKSHIRE COMPILED BY JOSEPH FOSTER AND AUTHENTICATED BY THE MEMBERS, OF EACH FAMILY VOL. fL—NORTH AND EAST RIDING LONDON: PRINTED AND PUBLISHED FOR THE COMPILER BY W. WILFRED HEAD, PLOUGH COURT, FETTER LANE, E.G. LIST OF PEDIGREES.—VOL. II. t all type refer to fa Hies introduced into the Pedigrees, i e Pedigree in which the for will be found on refer • to the Boynton Pedigr ALLAN, of Blackwell Hall, and Barton. CHAPMAN, of Whitby Strand. A ppleyard — Boynton Charlton— Belasyse. Atkinson— Tuke, of Thorner. CHAYTOR, of Croft Hall. De Audley—Cayley. CHOLMELEY, of Brandsby Hall, Cholmley, of Boynton. Barker— Mason. Whitby, and Howsham. Barnard—Gee. Cholmley—Strickland-Constable, of Flamborough. Bayley—Sotheron Cholmondeley— Cholmley. Beauchamp— Cayley. CLAPHAM, of Clapham, Beamsley, &c. Eeaumont—Scott. De Clare—Cayley. BECK.WITH, of Clint, Aikton, Stillingfleet, Poppleton, Clifford, see Constable, of Constable-Burton. Aldborough, Thurcroft, &c. Coldwell— Pease, of Hutton. BELASYSE, of Belasvse, Henknowle, Newborough, Worlaby. Colvile, see Mauleverer. and Long Marton. Consett— Preston, of Askham. Bellasis, of Long Marton, see Belasyse. CLIFFORD-CONSTABLE, of Constable-Burton, &c. Le Belward—Cholmeley. CONSTABLE, of Catfoss. Beresford —Peirse, of Bedale, &c. CONSTABLE, of Flamborough, &c. BEST, of Elmswell, and Middleton Quernhow. Constable—Cholmley, Strickland. Best—Norcliffe, Coore, of Scruton, see Gale. Beste— Best. Copsie—Favell, Scott. BETHELL, of Rise. Cromwell—Worsley. Bingham—Belasyse. -

William Bi'rtt Addrrssixg Thr Monthly

WILLIAM BI'RTT ADDRRSSIXG THR MONTHLY MEETING OF SOUTH-WEST DIVISION OF LINCOLNSHIRE, held at his house at \Velbourn North End, 1692. (See p. 83) F rontispiecc Vol. XXIX. J932 THE JOURNAL OF THE FRIENDS HISTORICAL SOCIETY Editor: NORMAN PENNEY, LL.D., F.S.A., F.R.Hist.S., 120 Richmond Park Road, Bournemouth, Hants. Publishing Office: Friends House, Euston Road, London, N.W.I. American Agency: 304 Arch Street, Philadelphia, Pa. Out Quofafton—23 " All scientific history nowadays must start from investigation of' sources.' It cannot be content to quote 'authorities' simply at their face value, but must press back behind the traditional statements to the evidence on which they, in turn, rest, and examine it independently and critically . how far the statements are removed from the events which they claim to discuss, and how nearly they are contemporary or first hand." F. R. BARRY, in The Study Bible, St. Luke, 1926 on Tftoor anb Being the presidential address delivered at the annual meeting of the Historical Society on the 3rd March. President of the Historical Society has two duties and privileges during his year of office : the first to preside at this meeting, the second to give an address. I cannot offer the charm with which Reginald Hine delighted us a year ago when he discoursed on the Quakers of Hertfordshire in the regrettable absence of the President ; nor can I offer a subject of general interest, such as Quaker language, discussed by T. Edmund Harvey previously. Vol. xxix.—290. 2 QUAKERISM ON MOOR AND WOLD I have limited myself to a strip of land on the north-east coast of Yorkshire, on the confines of civilization, as some southerners may say. -

The Infamous Shabbos Hagadol Massacre of the Jews of York In

The infamous Shabbos HaGadol massacre of the Jews by Baruch ben Chayil Ghastly Events of 1190 The ghastly Jews were not to be further persecuted, chain of events in York in 1190, which led but once he left for the Crusades the vio- of York in 1190 was the most notorious example of y British-born chavrusa, study to the rabbis placing a cherem against lence resumed. partner, in Telshe Stone first Jews living within the walls of that city, anti-Semitism in medieval England. Malerted me to the significance became the most notorious example of Refuge in York Castle One of the Jews of the infamous 1190 York pogrom. He anti-Semitism in medieval England. By at Westminster, Benedict of York, who has something of a personal connection no means, however, was it an isolated in- had chosen baptism to escape being with the affair, or at least with a related cident. The York massacre was the climax killed, later recanted his conversion to Clifford's Tower, site of the infamous massacre event that occurred subsequently in of a tide of murderous violence that had Christianity but died of his wounds. He of the Jews of York in 1190. The daffodils modern times. swept the country in the early part of 1190, had been the York agent for a prominent have been planted as an additional As a young man from a nonobservant when ignorant mobs were incited by the Jewish banker, Aaron of Lincoln. In memorial as they appropriately family that had survived the Holocaust, he leaders of the impending Crusades to pil- March 1190, his grieving widow and chil- display six petals actually attended the University of York lage and massacre whole Jewish commu- dren were slain in their beds and his house without knowing that British rabbis had nities. -

Court for Relief of Insolvent Debtors

21 George Crofts/late of No. 2, Cheyne-row, .Chelsea, Mid- Assignee by Order of the Court, having fi'ed dlesex, Commission Agents'. Assistant—In the Queen's . Prison. their Schedules, are ordered to be brought up John Benstead, late of West-street, Sheerness, Kent, Re- in Court, as hereinafter mentioned, at the tailer of Beer, and of No. 7, King's-row, St. John's, Court-House, in Portugal-Street, Lincoln's- South wark, out of business.—In the Debtors' Prison for Jnn, as follows, to be dealt with according London and Middlesex. Jean Etienne Alphonse de Lestre, late of No. 133, Salis- to the Statute: bury-square, Fleet-street, London, no trade or profession. - —In the Debtors' Prison for London and Middlesex. On Wednesday the 16th January 1850, at Ten William Odell, late of Beale-street, Houghton Regis, Bed- o'Clock precisely, before Mr. Commissioner ford, Whiting Manufacturer.—In the Debtors' Prison for Law. London and Middlesex. William Chequer, of No. 248, Blackfriars'-road, Surrey, Sad- James Bennett Moxey, late of No. 1, Crown-street, Wynd- dler, and Harnessmaker. ham-road, Camberwell, Surrey, Baker.—In the Debtors' Prison for. London and Middlesex. Robert Justice, late of No. 22, Portland-place, Clapham- George John Salter, late of Church-street, Rotherhithe, road, Surrey, Coal Merchant, previously of No. 1, Clay- , Surrey, Mariner.—In the Debtors' Prison for London lands-place, Clapham-road, Surrey, and formerly of No. and Middlesex. 1, Holland-place, Clapham-road aforesaid," Baker and James Bradley, late of No. 80, Beresford-street, Walworth, Coal Merchant Surrey, Traveller to an Ironfounder.—In the Queen's On Thursday the 17th January 1850, at Eleven Prison. -

The Best Day out in History

Visitor Information OPENING TIMES Open Daily: 9.30am – 5pm Kids Go Closed 25, 26 Dec and 1 Jan. Early closing 24 and 31 Dec, see website for details. FREE* ADMISSION THE BEST YMT Card Holder ..................................................................................................................FREE York Castle Adult (with 10% Gift Aid Donation) ........................................................................................£10.00 Adult (without donation) .......................................................................................................... £9.09 DAY OUT Prison Child (16 and under) * ...................................................................................FREE with a paying adult Access Day Ticket ** ............................................................................................................ £5.00 The museum buildings were once a ARE YOU A YORK RESIDENT? IN HISTORY Georgian prison, and down in the felons’ Valid York cardholders each receive 20% discount on admission! cells lies a dark and brutal history – a time WhetherTOY STORIESyou’re seven or 70, you’ll find your YMT Card NEW FOR 2017 YORK’S SWEET PAST of rogues, thieves and murderers. best-loved childhood toys here… and your 12 months unlimited access to Visit our infamous residents and parents’ and grandparents’ favourites too. York Castle Museum, York Art Gallery shiver at their stories of rough and the Yorkshire Museum. Share your memories of dolls and Lego, see our 100 YMT Card .............................................................................................£22 -

Street Name Subdivision/Multi-Family Elem. Middle High Note

Street Name Subdivision/Multi-Family Elem. Middle High Note 1st St (note) Old Donation North Rogers Staley Wakeland 9000 & high, N of Main St 1st St (note) Old Donation South Bright Staley Frisco 8800 block & lower, S of Main St 2nd St (note) Old Donation North Rogers Staley Wakeland 8900 & high, N of Main St 2nd St (note) Old Donation South Bright Staley Frisco 8800 block & lower, S of Main St 3rd St (note) Old Donation North Rogers Staley Wakeland 8900 & high, N of Main St 3rd St (note) Old Donation South Bright Staley Frisco 8800 block & lower, S of Main St 4th St (note) Old Donation North Rogers Staley Wakeland 8900 & high, N of Main St 4th St (note) Old Donation South Bright Staley Frisco 8800 block & lower, S of Main St 5th St (note) Old Donation North Rogers Staley Wakeland 8900 & higher, N of Main St 5th St (note) Old Donation South Bright Staley Frisco 8800 block & lower, S of Main St 6th St (note) Old Donation North Rogers Staley Wakeland 8900 & high, N of Main St 6th St (note) Old Donation South Bright Staley Frisco 8800 block & lower, S of Main St 7th St (note) Old Donation North Rogers Staley Wakeland 8900 & higher, N of Main St 7th St (note) Old Donation South Bright Staley Frisco 8800 block & lower, S of Main St Abberlet Dr Stonelake Estates West Sonntag Nelson Heritage Abberley Ln Shaddock Creek Estates, Ph 5-6 Carroll Griffin Wakeland Abbey Rd Preston Ridge/Kings Ridge Christie Clark Centennial Abbott Dr Creekside at Preston (west section) Tadlock Maus Heritage Abelia Dr Villages at Willow Bay (north) Mooneyham Maus Heritage -

The Scropfs of Bolton and of Masham

THE SCROPFS OF BOLTON AND OF MASHAM, C. 1300 - C. 1450: A STUDY OF A kORTHERN NOBLE FAMILY WITH A CALENDAR OF THE SCROPE OF BOLTON CARTULARY 'IWO VOLUMES VOLUME II BRIGh h VALE D. PHIL. THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY MAY 1987 VOLUME 'IWO GUIDE '10 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION CALENDAR OF THE SCROPE OF BOLTON CARTULARY 1 GUIDE '10 Call'ENTS page 1. West Bolton 1 2. Little Bolton or Low Bolton 7, 263 3. East Bolton or Castle Bolton 11, 264 4. Preston Under Scar 16, 266 5. Redmire 20, 265, 271 6. Wensley 24, 272 7. Leyburn 38, 273 8. Harmby 43, 274, 276 9. Bellerby 48, 275, 277 10. Stainton 57, 157 11. Downholme 58, 160 12. Marske 68, 159 13. Richmond 70, 120, 161 14. Newton Morrell 79, 173 15. rolby 80, 175 16. Croft on Tees 81, 174 17. Walmire 85 18. Uckerby 86, 176 19. Bolton on Swale 89, 177 20. Ellerton on Swale 92, 178, 228, 230 21. Thrintoft 102, 229 22. Yafforth 103, 231 23. Ainderby Steeple 106, 232 24. Caldwell 108, 140, 169 25. Stanwick St. John 111, 167 26. Cliff on Tees 112 27. Eppleby 113, 170 28. Aldbrough 114, 165 29. Manfield 115, 166 30. Brettanby and Barton 116, 172 31. Advowson of St. Agatha's, Easby 122, 162 32. Skeeby 127, 155, 164 33. Brampton on Swale 129, 154 34. Brignall 131, 187 35. Mbrtham 137, 186 36. Wycliffe 139, 168 37. Sutton Howgrave 146, 245 38. Thornton Steward 150, 207 39. Newbiggin 179, 227 40. -

York Museums Trust (YMT) Report Against Core Partnership Objectives January to June 2019

York Museums Trust (YMT) Report Against Core Partnership Objectives January to June 2019 Creation of museum and gallery provision capable of contributing to positioning York as a world class cultural centre 1. YMT has a four-year Business Plan for the years 2018-19 to 2021-22 which indicates how the Trust will pursue and achieve the five headlines priorities from its Forward Plan 2016-2021. Deliver the York Castle Museum (YCM) major capital project, including collection and storage rationalisation, and develop the Castle area as a cultural quarter. Excellent, high profile programming, including strategic YMT-led events to attract visitors to York and high quality exhibitions at York Art Gallery (YAG). Expanding Enterprises and fundraising activities, building on success, becoming a more business-like charity and increasing our income streams and resilience. Ensuring a 21st century Visitor Experience, pro-actively engaging visitors to sites and online Improving York’s and York Museums Trust’s profile through local, regional and international leadership, partnership and delivering on all expectations of key stakeholders. 2. The Business Plan specifies aims and measurable targets for the teams within the Trust to realise our ambitions. We have an Operational plan and report to Trustees each quarter on our performance and the operational KPIs. 3. One of the headline priorities is the redevelopment of the Castle Museum and the Castle Gateway. Planning for this initiative continues in close collaboration with CYC and the Castle Gateway Masterplan. We have accelerated the project to meet Castle Gateway Masterplan timeline with help from the Leeds City region pooled rates bid and are building a consensus with our own Castle Museum Advisory Group consisting of our stakeholders and neighbours.