Pdfbarbers Hill ISD Level Three Grievance.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter Fall 2010 (PDF)

Barbers Hill Independent School District EAGLE A Texas Exemplary School District Fall 2010 Superintendent Greg Poole, Ed.D. Board of Trustees THE POWER OF Carmena Goss, President Becky Tice, Vice President Benny May, Secretary George Barrera Cynthia Erwin Ron Mayfield Fred Skinner INSIDE School Board Connection p. 3 Tech Talk pp. 4-5 Friday Night LIghts pp. 6-7 New Faces, New Places p. 10 BLUE A Tradition of Excellence . by any measure BARBERS HILL ISD 2010 State Accountability Ratings Barbers Hill Primary Exemplary Superintendent’s Barbers Hill Elementary Exemplary Welcome Barbers Hill Intermediate Exemplary My favorite Barbers Hill Middle Exemplary track event is Barbers Hill High School Recognized the relay. There is something BHISD District Rating EXEMPLARY about the hand- ing of a baton by your teammate that elicits ex- ceptional effort. People would rather disappoint their own expectations than let the team down. Barbers Hill has been educating students since 1929 and it is one of the few dis- tricts that has maintained excel- lence throughout its long storied history. One of the drivers of this excel- lence is the determination of past and current leaders that the baton will not be dropped and that each graduating class will build on the past accomplishments and set the bar even higher. I am proud that the current staff and students are carrying on the proud traditions and excellence of “The Hill.” The challenge for the upcoming school year is simple: Make a great district even better! We truly have one of the best districts in the state and I cannot imagine a better place where students could get a better education. -

Barbers Hill High School

Barbers Hill Independent School District Educational Planning Guide Barbers Hill High School 2017-2018 Barbers Hill Independent School District 9600 Eagle Drive Mont Belvieu, TX 77580 Phone (281) 576-2221 Metro (281) 385-6038 Our Mission The Barbers Hill Independent School District provides instruction at the highest level of quality so that all students can learn to the best of their abilities and develop a positive self concept, regardless of socioeconomic or cultural background. The adopted goals and objectives are regarded as a commitment to strive for educational excellence and student achievement. ALL STUDENTS will be provided opportunities to acquire a knowledge of citizenship and responsibility as well as an appreciation of our global relationships and common American heritage, including its multicultural richness. ALL STUDENTS will be provided opportunities to develop the ability to think logically, independently, creatively, and to communicate effectively. ALL STUDENTS will also be encouraged to cultivate an intrinsic motivation for independent discovery beyond the school setting. Believing this, WE THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES, ADMINISTRATION, FACULTY, and STAFF of the BARBERS HILL INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT will assume responsibility for • maintaining accountability, • providing continuous improvement, • establishing lines of communication between the board of trustees, administration, faculty and staff of the district and parents, citizens, business leaders, industry leaders, civic organizations and officials of local governing -

Barbers Hill High School Student-Athlete Named Gatorade Texas Softball Player of the Year

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE [email protected] BARBERS HILL HIGH SCHOOL STUDENT-ATHLETE NAMED GATORADE TEXAS SOFTBALL PLAYER OF THE YEAR CHICAGO (June 18, 2021) — In its 36th year of honoring the nation’s best high school athletes, Gatorade today announced Sophia Simpson of Barbers Hill High School as its 2020-21 Gatorade Texas Softball Player of the Year. Simpson is the second Gatorade Texas Softball Player of the Year to be chosen from Barbers Hill High School. The award, which recognizes not only outstanding athletic excellence, but also high standards of academic achievement and exemplary character demonstrated on and off the field, distinguishes Simpson as Texas’ best high school softball player. Now a finalist for the prestigious Gatorade National Softball Player of the Year award to be announced in June, Simpson joins an elite alumni association of state award-winners in 12 sports, including Cat Osterman (2000-01, Cy Spring High School, Texas), Kelsey Stewart (2009-10, Arkansas City High School, Kan.), Carley Hoover (2012-13, D.W. Daniel High School, S.C.), Jenna Lilley (2012-13, Hoover High School, Ohio), Morgan Zerkle (2012-13, Cabell Midland High School, W. Va.), and Rachel Garcia (2014-15, Highland High School, Calif.). The 5-foot-10 senior right-handed pitcher led the Eagles to a 42-2 record and the Class 5A state championship this past season. Simpson compiled a 21-0 mark in the circle with a 0.18 earned run average, allowing just 36 hits and 24 walks to go with 271 strikeouts in 119.1 innings pitched. Simpson tossed four no-hitters with one perfect game and was the winning pitcher in seven of the Eagles’ 11 postseason victories. -

2020-2021 State Scores

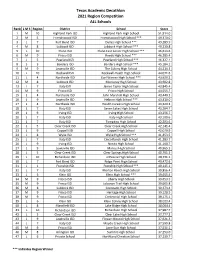

Texas Academic Decathlon 2021 Region Competition ALL Schools Rank L M S Region District School Score 1M 10 Highland Park ISD Highland Park High School 51,914.0 2M 5 Friendswood ISD Friendswood High School *** 49,370.0 3L 7 Fort Bend ISD Dulles High School *** 49,289.9 4M 8 Lubbock ISD Lubbock High School *** 49,230.8 5L 10 Plano ISD Plano East Senior High School *** 46,613.6 6M 9 Frisco ISD Reedy High School *** 46,385.4 7L 5 Pearland ISD Pearland High School *** 46,327.1 8S 3 Bandera ISD Bandera High School *** 45,184.1 9M 9 Lewisville ISD The Colony High School 44,214.3 10 L 10 Rockwall ISD Rockwall‐Heath High School 44,071.6 11 L 4 Northside ISD Earl Warren High School *** 43,929.2 12 M 8 Lubbock ISD Monterey High School 43,902.8 13 L 7 Katy ISD James Taylor High School 43,845.4 14 M 9 Frisco ISD Frisco High School 43,555.7 15 L 4 Northside ISD John Marshall High School 43,440.3 16 L 9 Lewisville ISD Hebron High School *** 43,410.0 17 L 4 Northside ISD Health Careers High School 43,320.3 18 L 7 Katy ISD Seven Lakes High School 43,264.7 19 L 9 Irving ISD Irving High School 43,256.7 20 L 7 Katy ISD Katy High School 43,109.6 21 L 7 Katy ISD Tompkins High School 42,203.6 22 L 5 Clear Creek ISD Clear Creek High School 42,141.4 23 L 9 Coppell ISD Coppell High School 42,070.9 24 L 8 Wylie ISD Wylie High School *** 41,453.5 25 L 7 Katy ISD Cinco Ranch High School 41,283.7 26 L 9 Irving ISD Nimitz High School 41,160.7 27 L 9 Lewisville ISD Marcus High School 40,965.3 28 L 5 Clear Creek ISD Clear Springs High School 40,761.3 29 L 10 Richardson -

Newsletter Summer 2018 (PDF)

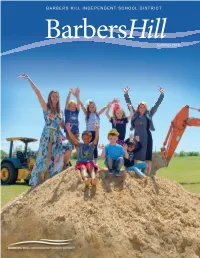

BARBERS HILL INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT BarbersHillSummer 2018 B cover: Groundbreaking of Building Excellence BH Early Childhood Center Barbers Hill ISD Administration Construction has been ongoing throughout the district in ful llment of projects approved by voters in Bonds 2013 and 2017. Barbers Hill High School will open Dr. Greg Poole new classroom and computer lab space to accommodate 500 students this fall (Bond Superintendent Bond 2013 – High SchoolECC Breaks Ground 2013). Both Middle School North and Middle School South will add classroom Sandra Duree space for 250 students each this fall, in addition to a competition gym at MSN and a Principal Lisa Watkins, Superintendent Greg Poole, and students break ground on Early theater at MSS (Bond 2017). Assistant Superintendent Childhood Center of Curriculum and Instruction Also approved in Bond 2017 was a new Early Childhood Center for grades Pre-K Stan Frazier High School Cafeteria Area F through First. Ground was broken this spring, and the new facility for our youngest Assistant Superintendent Dr. Greg Poole, Superintendent Concrete Slab of Planning and Operations I was recently wounded by a marshmallow. The bemused 10-year-old that caused Eagles is scheduled to open in fall, 2019. Plans are underway to renovate the existing Becky McManus my whelp explained with pride how he’d formed a marshmallow-launching Kindergarten Center and Primary School complex to an Administration building Assistant Superintendent contraption with the remnants of a water bottle and a balloon. It caused me to think that includes a new, larger Board room, and space for all departments, which are of Finance of marshmallows in a di erent way. -

Dragons Gameday Sunday, Sept

Dragons GameDay Sunday, Sept. 5, 2021 ⚫ Game # 108 Day Air Ballpark ⚫ Dayton, Ohio ⚫ 1:09 p.m. DH TV: Dayton’s CW (26) ⚫ Radio: 980 WONE Fox Sports Lansing Lugnuts (49-57) at Dayton Dragons (56-50) LH David Leal (0-4, 5.76)/RH Jeff Criswell (0-0, 0.00) vs. RH Carson Spiers (5-3, 4.14)/LH Evan Kravetz (0-0, 7.24) Today’s Game: The Dayton Dragons (affiliate of the Cincinnati Reds) meet the Lansing Lugnuts (affiliate of the Oakland Athletics) in a doubleheader. Both games are seven-inning games. These are the last two games of a six-game series. 2021 Season Series: Dayton 13, Lansing 9. (At Dayton: Dragons 6, Lugnuts 4). Current Series: Dragons 3, Lugnuts 1. Last Game: Saturday: The Dragons and Lugnuts were postponed by rain. Current Series with Lansing: The Dragons are 3-1. They are batting .302 as a team with 14 runs scored (3.5 per game) while posting an ERA of 2.25 and committing nine errors. They have stolen nine bases. Last Series vs. Fort Wayne: The Dragons went 3-3. They batted .245 and scored 26 runs (4.3 per game) while posting an ERA of 5.71 and committing six errors. They had 15 stolen bases in the series, matching their highest total in a series this year. Their 20 extra base hits tied for third most in a series. The Dragons roster includes eight players ranked among the top-20 prospects in the Reds organization. In the recently-updated MLB.com rankings, Matt McLain is the #4 prospect in the Reds system; Mat Nelson is #10, Michael Siani is #12, Lyon Richardson is #14, Christian Roa is #15, Bryce Bonnin is #16, Ivan Johnson is #17, and Allan Cerda is #18. -

Texas HOSA 2021 State Leadership Recognition & Scholarship

Texas HOSA 2021 State Leadership Recognition & Scholarship HOSA Service Project HOSA Service Project- HATS Activity Tracking Deadline: HOSA members may continue to accrue service hours and donations until May 15. HOSA will pull reports of all APPROVED hours/donations for ILC recognition. Local Advisors are encouraged to login to the system and approve all needed hours prior to May 15. Certificate of Merit Atascocita High School 6560 Byron P. Steele II High School 1147 Seguin High School 1104 1 Barbara James Service Award Barbara James Service Award- HATS Activity Tracking Deadline: HOSA members may continue to accrue service hours and donations until May 15. HOSA will pull reports of all APPROVED hours/donations for ILC recognition. Local Advisors are encouraged to login to the system and approve all needed hours prior to May 15. Bronze Level Leander High School 1139 Bhasin, Ishika McNeil High School 1965 Ko, Chrisitna Coppell High School 3204 Sreemushta, Sanjitha John B. Connally High School 1175 Unegbu, Crystal John B. Connally High School 1175 Vaquera, Viviana A&M Consolidated High School 2020 Mendez, Robert John B. Connally High School 1175 Le, Kimberly John B. Connally High School 1175 Wissman, Austin Westwood High School 1092 Sultan, Nabila Westwood High School 1018 Manwani, Serena Coppell High School 3204 Maramraju, Sudhiksha Westwood High School 1052 Arunkumar, Jyotsna Robert Turner High School 2005 Rodriguez, Stephanie McNeil High School 1119 Yeladandi, Meghna Westwood High School 1018 Waghmare, Vidula John B. Connally High School 1175 Martinez, Emily John B. Connally High School 1175 Luu, Hannah Coppell High School 3195 Balaji, Ananya Westwood High School 1018 Malpani, Nidhi James Madison High School 1004 Barajas, Gabriella John B. -

2015-16 Volleyball All-State Selections

2015-16 TGCA Volleyball All-State Selections Athlete First Athlete Last High School Coach First Coach Last Grade Conf. 1A Gentyre Munden BLUM HIGH SCHOOL Lauren McPherson Sophomore 1A Allison Rosenbaum BURTON HIGH SCHOOL Katie Cloud Junior 1A Blaire Smith BURTON HIGH SCHOOL Katie Cloud Junior 1A Sarah Craft DHANIS HIGH SCHOOL Courtney Rodriguez Senior 1A Yani Ponce FORT DAVIS HIGH SCHOOL Gary Lamar Junior 1A Sydney Ritter GARY HIGH SCHOOL Tamika Hubbard Senior 1A Leann Youngblood GARY HIGH SCHOOL Tamika Hubbard Sophomore 1A Madison Karr KOPPERL SCHOOL Trava G Smith Junior 1A Reanna Miller KOPPERL SCHOOL Trava G Smith Sophomore 1A Madison Mooney KOPPERL SCHOOL Trava G Smith Freshman 1A Logan Smith KOPPERL SCHOOL Trava G Smith Freshman 1A Kasey Scott LEVERETTS CHAPEL HIGH SCHOOL Rickey Hammontree Junior 1A Priscilla Serrano MARFA JR/SR HIGH SCHOOL Amy White Junior 1A Makinna Serrata MCMULLEN COUNTY HIGH SCHOOL Darcy Remmers Sophomore 1A Hannah Garrison MEDINA HIGH SCHOOL Lovey Sockol Senior 1A Rosa Schones MILLER GROVE HIGH SCHOOL Gary Billingsley Freshman 1A Kristen Kuehler MUNDAY SECONDARY SCHOOL Jessica Toliver Sophomore 1A Robin Diserens NORTH ZULCH HIGH SCHOOL Gregory Horn Junior 1A Mackenzie Horn NORTH ZULCH HIGH SCHOOL Gregory Horn Senior 1A Sally Osth NORTH ZULCH HIGH SCHOOL Gregory Horn Sophomore 1A Brittany Hohlt ROUND TOP‐CARMINE HIGH SCHOOL RaChelle Etzel Senior 1A Adyson Lange ROUND TOP‐CARMINE HIGH SCHOOL RaChelle Etzel Senior 1A Emma Leppard ROUND TOP‐CARMINE HIGH SCHOOL RaChelle Etzel Senior 1A Jordan Peters ROUND TOP‐CARMINE -

SCHOOL RATINGS Distinctions & Designations

Ratings by ISD Greater Houston Area Student Progress Student Achievements SCHOOL RATINGS Distinctions & Designations 2019 oldrepublictitle.com/Houston 09/2019 | © Old Republic Title | This material is for educational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. We assume no liability for errors or omissions. Old Republic Title’s underwriters are Old Republic National Title Insurance Company and American Guaranty Title Insurance Company. | SW-HOU-PublicSchoolRatings-2019 | SWTD_SS_0094 TEXAS EDUCATION AGENCY ACCOUNTABILITY RATING SYSTEM DISTRICTS AND CAMPUSES RECEIVE AN OVERALL RATING, AS WELL AS A RATING FOR EACH DOMAIN. • A, B, C, or D: Assigned for overall performance and for performance in each domain to districts and campuses (including those evaluated under alternative education accountability [AEA]) that meet the performance target for the letter grade • F: Assigned for overall performance and for performance in each domain to districts and campuses (including AEAs) that do not meet the performance target to earn at least a D. • Not Rated: Assigned to districts that—under certain, specific circumstances—do not receive a rating. NOTE: Single-campus districts must meet the performance targets required for the campus in order to demonstrate acceptable performance. The Texas Education Agency looks at three domains in determining a school’s accountability rating: Evaluates performance across all subjects for all Student students, on both general and alternate assessments, Achievement College, Career, and Military Readiness (CCMR) indicators, and graduation rates. Measures district and campus outcomes in two areas: the School number of students that grew at least one year academically (or are on track) as measured by STAAR results and the achievement Progress of all students relative to districts or campuses with similar economically disadvantaged percentages. -

Barbers Hill Sports Hall of Honor Qualifications for Induction

BARBERS HILL SPORTS HALL OF HONOR QUALIFICATIONS FOR INDUCTION General Qualifications Each inductee shall be a graduate of Barbers Hill High School and must have participated as a student athlete in the Barbers Hill Independent School District Athletic Program. All individuals and team members as may be considered for induction must be of outstanding moral character as may be determined at the sole discretion of the Committee. Time Requirements Both individual and team nominations shall require a minimum of five years time lapse since the date of class graduation. Team Qualifications For team sports including football, basketball, softball or baseball, teams which participated in the time period prior to the inception of a state-level playoff system must have won a district championship or bi-district championship. All other teams, with the addition of volleyball from the team sports listed above, considered must have qualified as regional finalists or at levels above. For team sports including cross country, track and field, golf, tennis teams must have been state qualifiers. Individual Qualifications To be qualified for individual induction in football, basketball, softball, baseball or volleyball, the candidate shall meet at least one of the following criteria: (a) recognition as a first or second team all-state team member or selection as a participant in a recognized coaches association all-star game (b) participation in athletic competition at the collegiate level (c) participation in athletic competition at a professional level -

(713) 525-3500 Or Admiss

Find the school district in which your Houston high school is located. For Private high schools, search for your school under the "Private" heading. If you are unable to determine your UST Admissions Couselor, please contact the Office of Admissions at (713) 525-3500 or [email protected] Aldine Independent School District Aldine Senior High School Arthur Ortiz [email protected] 713-525-3848 Eisenhower High School Arthur Ortiz [email protected] 713-525-3848 H P Carter Career Center Arthur Ortiz [email protected] 713-525-3848 J. L. Anderson Academy Arthur Ortiz [email protected] 713-525-3848 MacArthur High School Arthur Ortiz [email protected] 713-525-3848 Nimitz High School Arthur Ortiz [email protected] 713-525-3848 Victory Early College HS Arthur Ortiz [email protected] 713-525-3848 W T Hall High School Arthur Ortiz [email protected] 713-525-3848 G W Carver High School Arthur Ortiz [email protected] 713-525-3848 Aleif Independent School District Alief Hasting Senior High Sch Goli Ardekani [email protected] 713-942-3468 Alief Taylor High School Goli Ardekani [email protected] 713-942-3468 Elsik High School Goli Ardekani [email protected] 713-942-3468 Kerr High School Arthur Ortiz [email protected] 713-525-3848 Alvin Independent School District Alvin High School Goli Ardekani [email protected] 713-942-3468 Manvel Goli Ardekani [email protected] 713-942-3468 Anahuac Independent School District Anahuac High School Mi'Chelle Bonnette [email protected] 713-942-3475 Angleton Independent School District Angleton High School Mi'Chelle Bonnette -

That Champion Season Pass Them Along to You

Leaguer Out of the mouths of babes ALL SMILES. Austin By LORETTA ENGLISH Westlake players celebrate after Did you see the full moon eclipsed by the upsetting lop-ranked shadow of the earth on the Sunday night after Northwest Justin in Thanksgiving? Surrendering to Middle of the the finals, The victory Night insomnia, I put on a coat and went out into was the Chaps' the cold night to see what I could see. My youngest second state title in child was born 12 years ago on another total eel ipse three years. Below, of the full moon, only then we were in the middle Brian Peel and of a heat wave. Moses Garcia of San 1 stood in my front yard and looked up at the Antonio Churchill night sky through the bare branches of the pecan. celebrate a point The shadow of the earth was sailing slowly past the scored against Klein moon like the darkest of clouds and the moon was in the semifinals of surrounded by a white aura and a red orange ring. the state team tennis The world is a strange and wondrous place, tournament. mysterious to all of us, and especially as seen through Photos b) JOEY UN. the eyes of children. Following are quotes of fifth and sixth graders that we find so original, so scientifically and spiri tually beguiling in their world view, that we had to That champion season pass them along to you. * You can listen to thunder after lightening Any state championship team is special. frustration fot the Cougars, who and tell how close you came to getting hit.