Climate-Induced Community Relocations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Implementing a HBIM Approach to Manage the Translocation of Heritage Buildings

Implementing a HBIM approach to manage the translocation of heritage buildings Purpose The purpose of the paper is to present a study which exploited synergies between the fields of Heritage BIM, conservation and building translocation to develop a new approach to support a digitally enabled translocation process. The translocation (or relocation) of buildings or structures is a niche area of the construction sector and much of the significant work in this field has focused on the relocation of heritage buildings. However, hitherto there was a paucity of work integrating translocation with the process and technology of BIM. Design/Methodology/Approach The study employed a Constructive Research approach to analyse the phenomenon of heritage translocation. As part of this approach, semi structured interviews were undertaken with professionals engaged in heritage translocation projects within the UK and this was supported by a multi-faceted review of literature within the cross cutting themes of translocation and HBIM. Building on the results, a BIM enabled process was implemented to support the translocation of a 19th Century timber framed building in the UK. Findings Following analysis of results of semi structured interviews, and supported by findings from prevailing literature in the field of translocation and HBIM, a HBIM for Translocation Conceptual Framework (TransHBIM) was developed. Building on the key constructs of the framework, a HBIM based workflow was implemented to develop a digitally enabled translocation process which provided a new approach to managing and documenting heritage translocation where disassembly and reconstruction is utilised. The workflow provided a more effective way of documenting individual elements of the building within a digital environment opening up potential for new simulation of the entire process. -

Building Structure Relocation

Building structure relocation Victor Verstichele MASTER’S THESIS May 2020 Construction Engineering ABSTRACT Tampereen ammattikorkeakoulu Tampere University of Applied Sciences Master Construction Engineering VICTOR VERSTICHELE: Building structure relocation Masters thesis 69 pages, appendices 1 page May 2020 Building structure relocation is the process of physically moving a structure to a predefined location and has been practiced in many parts of the world for centu- ries. Presently building relocation can be considered as a last resort of preserva- tion when buildings are threatened by demolition or destruction. Due to the grow- ing awareness of building preservation and the improvement in techniques and reliability, the relocation of building structures is becoming an approved preser- vation method. Next to being a method of preservation, buildings are presently being relocated for various reasons due to the specialization and democratization of the process. A building and certainly a relocation project is never the same, therefore creativ- ity, experience, and good engineering solutions are needed to make the move a success. The planning of the relocation and more specifically the determination of the method and the techniques is a key step in the relocation process. This thesis tries to provide a general summary of the entire relocation process, based on recent case studies of relocation projects, relocation companies' expe- riences, and articles. All the steps to be taken to relocate a building are discussed in a chronological way, answering the big ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions. Eventually, the relocation of the tavara-asema building in Tampere is discussed as an exam- ple of the challenges that may occur in the process. -

Buffalo Avenue Heritage District Revitalization Strategy

Buffalo Avenue Heritage District Revitalization Strategy August, 2009 Prepared for: Prepared by: USA Niagara City of Development Niagara Falls Corporation REVITALIZATION STRATEGY TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................ v Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 1 WHY BUFFALO AVENUE? ITS HERITAGE ............................................................................................................................. 2 PURPOSE ............................................................................................................................................................................... 3 GUIDING PRINCIPLES ........................................................................................................................................................... 4 ISSUES FACING THE DISTRICT ............................................................................................................................................ 6 The Vision ........................................................................................................................................... 8 20-YEAR ILLUSTRATIVE SITE PLAN .............................................................................................................. 9 Elements of the Vision ...................................................................................................................... -

Essay 1: Housing Factors Affecting Mobility: the Impact on Corporate Transfers

THREE ESSAYS ON SELLERS’ BEHAVIOR IN THE HOUSING MARKET SVETOSLAVA ALEXANDROVA Bachelor of Business Administration Cleveland State University May 2003 Master of Business Administration Cleveland State University May 2007 Submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY MAY 2017 ©COPYRIGHT BY SVETOSLAVA ALEXANDROVA 2016 We hereby approve this dissertation for Svetoslava Alexandrova Candidate for the Doctor of Business Administration degree for the Department of Finance And CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERTSITY College of Graduate Studies by ___________________________________________ Committee Chair, Dr. Alan Reichert Department of Finance/October 6th, 2015 ___________________________________________ Committee Co-Chair, Dr. Haigang Zhou Department of Finance/October 6th, 2015 ___________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Dieter Gramlich Baden-Wuerttemberg Cooperative University/October 6th, 2016 ___________________________________________ Dr. Walter Rom Department of Operations and Supply Chain Management/October 6th, 2015 October 6th, 2015 ___________________________________________ Date of Defense THREE ESSAYS ON SELLERS’ BEHAVIOR IN THE HOUSING MARKET SVETOSLAVA ALEXANDROVA ABSTRACT Housing markets exhibit some puzzling behavior that cannot be completely explained by rational market dynamics. The neoclassical economic theory posits that rational sellers and rational buyers in the housing market will look at the current market price in order to determine a value of a property. Studies, however, show that physiological biases may affect the decision- making process of both sellers and buyers. I examine the behavior of sellers in the housing market in three different settings. In essay 1, I analyze the effects of the health of the housing market on mobility. In Essay 2, I study the effects of sellers’ loss aversion on listing price and time on the market within the prospect theory framework. -

Korea's Economy

2014 Overview and Macroeconomic Issues Lessons from the Economic Development Experience of South Korea Danny Leipziger The Role of Aid in Korea's Development Lee Kye Woo Future Prospects for the Korean Economy Jung Kyu-Chul Building a Creative Economy The Creative Economy of the Park Geun-hye Administration Cha Doo-won The Real Korean Innovation Challenge: Services and Small Businesses KOREA Robert D. Atkinson Spurring the Development of Venture Capital in Korea Randall Jones ’S ECONOMY VOLUME 30 Economic Relations with Europe KOREA’S ECONOMY Korea’s Economic Relations with the EU and the Korea-EU FTA apublicationoftheKoreaEconomicInstituteof America Kang Yoo-duk VOLUME 30 and theKoreaInstituteforInternationalEconomicPolicy 130 years between Korea and Italy: Evaluation and Prospect Oh Tae Hyun 2014: 130 Years of Diplomatic Relations between Korea and Italy Angelo Gioe 130th Anniversary of Korea’s Economic Relations with Russia Jeong Yeo-cheon North Korea The Costs of Korean Unification: Realistic Lessons from the German Case Rudiger Frank President Park Geun-hye’s Unification Vision and Policy Jo Dongho Kor ea Economic Institute of America Korea Economic Institute of America 1800 K Street, NW Suite 1010 Washington, DC 20006 KEI EDITORIAL BOARD KEI Editor: Troy Stangarone Contract Editor: Gimga Group The Korea Economic Institute of America is registered under the Foreign Agents Registration Act as an agent of the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, a public corporation established by the Government of the Republic of Korea. This material is filed with the Department of Justice, where the required registration statement is available for public inspection. Registration does not indicate U.S. -

Moving Historic Buildings: a Study of What Makes Good Preservation

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2008 Moving Historic Buildings: A Study of What Makes Good Preservation Practices When Dealing with Historically Significant Buildings and Structures Xana Peltola Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Recommended Citation Peltola, Xana, "Moving Historic Buildings: A Study of What Makes Good Preservation Practices When Dealing with Historically Significant Buildings and Structures" (2008). All Theses. 352. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/352 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MOVING HISTORIC BUILDINGS: A STUDY OF WHAT MAKES GOOD PRESERVATION PRACTICES WHEN DEALING WITH HISTORICALY SIGNIFICANT BUILDINGS AND STRUCTURES A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Schools of Clemson University and The College of Charleston In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Historic Preservation by Xana Colleen Peltola May 2008 Accepted by: Jennifer McStotts, Committee Chair Robert D. Russell, Jr. Jonathan Poston Ashley Robbins ABSTRACT When relocating in order to preserve an historic property, there must be certain protocols in place to ensure that the historic significance is retained. Historic preservationists are not only attempting to successfully relocate a building but also to follow good preservation ethics in order to respect the current and potential site as well as the structure itself. In addition to examining how historic structures have been moved in the past and the guidelines that the National Register has developed regarding the process by which historic structures should be relocated, two case studies will also be examined. -

Relocation: Transforming Where and How Government Works

Relocation: transforming where and how government works Ian R. Smith March 2010 Relocation: transforming where and how government works March 2010 Official versions of this document are printed on 100% recycled paper. When you have finished with it please recycle it again. If using an electronic version of the document, please consider the environment and only print the pages which you need and recycle them when you have finished. © Crown copyright 2010 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Coat of Arms and departmental logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. For any other use of this material please write to Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU or e-mail: [email protected] ISBN 978-1-84532-712-5 PU949 Contents Page Foreword 3 Chapter 1 Executive Summary 5 Chapter 2 Recommendations and next steps 13 Chapter 3 Introduction 17 Chapter 4 The current relocation programme 23 Chapter 5 2010: The case for change 31 Chapter 6 A vision for location 39 Chapter 7 Stronger Centralised Mechanisms 45 Chapter 8 Improving relocation costs and benefits 51 Chapter 9 Outcomes 61 Chapter 10 Case Study: Ministry of Justice 69 Relocation: transforming where and how government works 1 Foreword Letter from Ian Smith to the Chancellor of the Exchequer You asked me to lead an independent review on the scope for further government relocations from London and the South East as part of your drive to create a “smarter government”. -

The Vitality and Resilience of Inherited Japanese Houses -100 Years of Shimizu-Gumi Houses-

The Vitality and Resilience of Inherited Japanese Houses -100 Years of Shimizu-gumi Houses- Preface Since its foundation in 1804, residential architecture had been one of the primary business focuses for Shimizu-gumi, the present Shimizu Corporation. Many books have been published to showcase its works, such as Sekkei zushū, jūtaku no maki, ji 1907 nen shi 1923 nen (Drawing collection: house, from 1907 to 1923) and Sekkei zushū, shitsunai narabini kagu dentō no maki, ji 1909 nen shi 1913 nen (Drawing collection: interior, furniture and lighting, from 1909 to 1913). These books feature painted drawings of large houses, which could be considered mansions in the Western sense, designed and built by Shimizu-gumi, and include plans, elevations, development plans, and illustrations of furniture. The books enable the reader to visualize many aspects of mansions in the Meiji era (1868-1912) and Taisho era (1912-1926,) and to understand how these mansions were significant as elements of urban culture. Additionally, an academic work based on these earlier texts was published to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the Housing Research Foundation JUSOKEN: Meiji/Taisho no teitaku, Shimizu-gumi sakusei saishiki-zu no sekai (Mansions in Meiji and Taisho, the world of colored drawings created by Shimizu-gumi, Kashiwashobo, 2009, currently unavailable). This book is the product of joint research by “Shimizu Kensetsu Teitaku Shiryō Kenkyūkai” (Shimizu Corporation Mansion Document Study Group, 2004 to 2009) in the “Jūtaku Shiryō Iinkai” (Committee for historical materials about houses) of Jusoken. For the next phase of study, surveys and research on Jūtaku kenchiku zushū (Residential architecture catalog, 1st volume: 1935, 2nd volume: 1939) should be conducted. -

Special Meetings

Page 1 of 82 CARBONDALE TOWN HALL March 7, 2019 6:30 P.M. TIME* ITEM DESIRED OUTCOME 6:30 1. Roll Call 6:30 2. Approval of Minutes: August 2018 ATTACHMENT A 6:35 3. Persons present not on the agenda. 6:40 4. Public Hearing: SOM Study 7:00 5. Board Training ATTACHMENT a. Chapter 16 of Carbondale B & C Municipal Code b. Adopted Design Guidelines 7:25 6. Adjourn * Please Note Times Are Approximate Page 2 of 82 MINUTES CARBONDALE HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMISSION August 23, 2018 CALL TO ORDER Nick Miscione called the August 23, 2017 meeting to order at 6:30 p.m. ROLL CALL The following members were present for roll call: Members: Ashley Allis, Member Carole Klein, Member Nick Miscione, Interim Chair Eric Doud, Member Town Staff Present: Angie Sprang, Boards & Commissions Clerk John Leybourn, Staff Liaison CONSENT AGENDA Motion Passed: Ashley Allis moved to approve Carbondale Historic Preservation Commission (CPHC) meeting minutes from November 2017. Nick Miscoine, seconded the motion, and it was unanimously approved. PERSONS PRESENT NOT ON THE AGENDA There was no one present wished to address the board. 40 N 4TH ST REVIEW Daniel Furgeson and John Ford presented the project specifics to the Board. They showed an artistic rendering of the plan changes, and described the proposed changes. Discussion ensued, points made were: • The building has not been deemed a building of merit • It was built a century ago • Concrete w/o rebar, timber frame on inside & conventional framing on the outside • The building has been altered considerably • Offices upstairs are occupied by the owner and they will remain as is • The restaurant will have more seating place as the former layout has a great deal of storage Staff noted that the plan is straight forward and has been reviewed and approved. -

Gore Place Technical Report

REPORT ON THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE EXAMINATION OF THE ENTRANCE DRIVE, CARRIAGE HOUSE, GREENHOUSE, VEGETABLE GARDEN, FLOWER GARDEN AND GRAPERY AT GORE PLACE, WALTHAM, MASSACHUSETTS FISKE CENTER FOR ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS BOSTON CULTURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT STUDY NO. 17 2006 Cover Illustration: Detail of the Gore Place property as depicted by the Historic American Buildings Survey in 1936. REPORT ON THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITE EXAMINATION OF THE ENTRANCE DRIVE, CARRIAGE HOUSE, GREENHOUSE, VEGETABLE GARDEN, FLOWER GARDEN AND GRAPERY AT GORE PLACE, WALTHAM, MASSACHUSETTS PREPARED FOR GORE PLACE SOCIETY BY J.N. LEITH SMITH AND GREGORY DUBELL FISKE CENTER FOR ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS BOSTON CULTURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT STUDY NO 17 2006 Fiske Center for Archaeological Research The Fiske Center for Archaeological Research and protect the cultural heritage and historic (formerly the Center for Cultural and landscape of the Commonwealth of Environmental History) was established in 1996 Massachusetts and the surrounding region. As a with a mission that includes research, public public service unit of the Department of service, and educational initiatives. The Center Anthropology, the FCAR also serves an impor- maintains archaeology and conservation labora- tant educational role at the University of tories and supports research in landscape and Massachusetts, Boston by creating opportunities environmental archaeology, historical archaeol- for students to participate in public service proj- ogy, and environmental history. Center projects ects. often have an applied focus, seeking to promote ii ABSTRACT A landscape restoration plan for the 45-acre Gore architectural remains that include fragments of Place property in Waltham and Watertown, MA, marble tile flooring identical to that in the Gore calls for restoration of grounds, gardens and Mansion. -

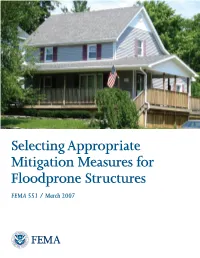

Selecting Appropriate Mitigation Measures for Floodprone Structures FEMA 551 / March 2007

Selecting Appropriate Mitigation Measures for Floodprone Structures FEMA 551 / March 2007 FEMA About the Cover The house pictured on the cover, located in Michigan, was elevated approximately five feet. The basement was abandoned, filled, and the house placed upon a new extended wall foundation with a crawlspace. Twelve hydrostatic vent openings were installed to allow any floodwater to enter the crawlspace. The deck and wrap-around porch was added at the owner’s expense to improve the overall aesthetics of the site. The project was completed utilizing Flood Mitigation Assistance Funds for 75 percent of the project’s cost. The community paid 12.5 percent of the cost and the home owner the remaining 12.5 percent. Total cost of the elevation project was $49,140, completed in 2001. Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction....................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Intended Users and Purpose of This Manual ...................................................... 1-1 1.2 Organization of This Manual.............................................................................. 1-2 1.3 Available Resources............................................................................................ 1-3 Chapter 2 The National Tool (NT).................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 Starting Data ....................................................................................................... 2-1 2.2 NT Contents ...................................................................................................... -

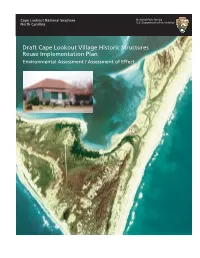

Draft Cape Lookout Village Historic Structures Reuse Implementation Plan Environmental Assessment / Assessment of Effect

Cape Lookout National Seashore National Park Service North Carolina U.S. Department of the Interior Draft Cape Lookout Village Historic Structures Reuse Implementation Plan Environmental Assessment / Assessment of Effect . Draft Cape Lookout Village Historic Structures Reuse Implementation Plan / Environmental Assessment / Assessment of Effect Cape Lookout National Seashore Carteret County, North Carolina ____________________________________________________________________________________ Cape Lookout National Seashore is in Carteret County, North Carolina, about 3 miles off the mainland coast. The national seashore occupies more than 28,000 acres of land and water extending from Ocracoke Inlet on the northeast to Beaufort Inlet on the southwest. The national seashore consists of four main barrier islands (North Core Banks, Middle Core Banks, South Core Banks, and Shackleford Banks). Various historic maritime activities have occurred within the national seashore, and the islands attract visitors seeking a diverse range of recreational opportunities. This project concerns the Cape Lookout Village Historic District, which is near the southern end of the national seashore on the South Core Banks. The district has historically served as a site of maritime navigation and life- saving services, commercial fishing, and private residential and recreational use. The National Park Service (NPS) proposes to evaluate a range of alternative uses for 16 residences in the Cape Lookout Village Historic District. Although exhibiting various degrees of structural deterioration, all but three buildings are identified as contributing to the district’s national register significance. Essential utility systems would be required for any alternative proposal for reuse of the buildings. This document examines six alternatives for alternatives uses of the buildings in the Cape Lookout Village Historic District for the next 25 years.