Summer 2019 Brooklyn Bird Club’S the Clapper Rail Summer 2019 Inside This Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulletin No. 206-Treehopper Injury in Utah Orchards

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU UAES Bulletins Agricultural Experiment Station 6-1928 Bulletin No. 206 - Treehopper Injury in Utah Orchards Charles J. Sorenson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/uaes_bulletins Part of the Agricultural Science Commons Recommended Citation Sorenson, Charles J., "Bulletin No. 206 - Treehopper Injury in Utah Orchards" (1928). UAES Bulletins. Paper 178. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/uaes_bulletins/178 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Agricultural Experiment Station at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in UAES Bulletins by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bulletin 2 06 June, 1928 Treehopper Injury in Utah Orchards By CHARLES J. SORENSON 3 Dorsal and side views of the following species of treehoppers: 1. Ceresa bubalus (Fabr.) ( Buffalo treehopper) 2. Stictocephala inermis (Fabr.) 3. Stictocephala gillettei Godg. (x 10 ) UTAH AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION LOGAN. UTAH UTAH AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION , BOARD OF TRUSTEES . ANTHONY W. IVINS, President __ _____ ____________________ __ ___________________ Salt Lake City C. G. ADNEY, Vice-President ____ ___ ________________________________ ________________________ Corinne ROY B ULLEN ________ __________________________ _______ _____ _____ ________ ___ ____ ______ ____ Salt Lake City LORENZO N . STOHL ______ ___ ____ ___ ______________________ __ ___ ______ _____ __________ Salt Lake City MRS. LEE CHARLES MILLER ___ ______ ___ _________ ___ _____ ______ ___ ____ ________ Salt Lake City WE S TON V ERN ON, Sr. ________________________ ___ ____ ____ _____ ___ ____ ______ __ __ _______ ________ Loga n FRANK B. STEPHENS _____ ___ __ ____ ____________ ____ ______________ __ ___________ __.___ Salt Lake City MRS. -

Integrated Pest Management for Home Gardens: Insect Identification and Control

Insect Pests July 2003 IP-13 Integrated Pest Management for Home Gardens: Insect Identification and Control Richard Ebesu Department of Plant and Environmental Protection Sciences ntensive, high-production agricultural systems have IPM components and practices Itraditionally used synthetic pesticides as the primary Integrated pest management strategies consist of site tool to eliminate pests and sustain the least amount of preparation, monitoring the crop and pest population, economic damage to the crop. Dependence on these pes problem analysis, and selection of appropriate control ticides has led to development of pest resistance to pes methods. Home gardeners can themselves participate in ticides and increased risk to humans, other living or IPM strategies and insect control methods with a little ganisms, and the environment. knowledge and practice. Integrated pest management (IPM) is a sustainable approach to managing pests that combines biological, Preparation cultural, physical, and chemical tools in a way that mini What control strategies can you use before you plant? mizes economic, health, and environmental risks. You need to be aware of potential problems and give The objective of IPM is to eliminate or reduce po your plants the best chance to grow in a healthy envi tentially harmful pesticide use by using a combination ronment. of control methods that will reduce the pest to an ac ceptable level. The control methods should be socially Soil preparation acceptable, environmentally safe, and economically Improve the physical properties of the soil including practical. Many commercial agricultural systems use texture and drainage to reduce waterlogging. Improve IPM methods to manage pest problems, and home gar soil fertility and soil organic matter by working well deners can use similar methods to control pest problems rotted compost into the soil. -

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations Spring 2010 Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras YEN-WEN CHENG University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Art and Architecture Commons, Asian History Commons, and the Cultural History Commons Recommended Citation CHENG, YEN-WEN, "Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras" (2010). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 98. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/98 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/98 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras Abstract After obtaining sovereignty, a new emperor of China often gathers the imperial collections of previous dynasties and uses them as evidence of the legitimacy of the new regime. Some emperors go further, commissioning the compilation projects of bibliographies of books and catalogues of artistic works in their imperial collections not only as inventories but also for proclaiming their imperial power. The imperial collections of art symbolize political and cultural predominance, present contemporary attitudes toward art and connoisseurship, and reflect emperors’ personal taste for art. The attempt of this research project is to explore the practice of art cataloguing during two of the most important reign periods in imperial China: Emperor Huizong of the Northern Song Dynasty (r. 1101-1125) and Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty (r. 1736-1795). Through examining the format and content of the selected painting, calligraphy, and bronze catalogues compiled by both emperors, features of each catalogue reveal the development of cataloguing imperial artistic collections. -

Web-Book Catalog 2021-05-10

Lehigh Gap Nature Center Library Book Catalog Title Year Author(s) Publisher Keywords Keywords Catalog No. National Geographic, Washington, 100 best pictures. 2001 National Geogrpahic. Photographs. 779 DC Miller, Jeffrey C., and Daniel H. 100 butterflies and moths : portraits from Belknap Press of Harvard University Butterflies - Costa 2007 Janzen, and Winifred Moths - Costa Rica 595.789097286 th tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA rica Hallwachs. Miller, Jeffery C., and Daniel H. 100 caterpillars : portraits from the Belknap Press of Harvard University Caterpillars - Costa 2006 Janzen, and Winifred 595.781 tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA Rica Hallwachs 100 plants to feed the bees : provide a 2016 Lee-Mader, Eric, et al. Storey Publishing, North Adams, MA Bees. Pollination 635.9676 healthy habitat to help pollinators thrive Klots, Alexander B., and Elsie 1001 answers to questions about insects 1961 Grosset & Dunlap, New York, NY Insects 595.7 B. Klots Cruickshank, Allan D., and Dodd, Mead, and Company, New 1001 questions answered about birds 1958 Birds 598 Helen Cruickshank York, NY Currie, Philip J. and Eva B. 101 Questions About Dinosaurs 1996 Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, NY Reptiles Dinosaurs 567.91 Koppelhus Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, N. 101 Questions About the Seashore 1997 Barlowe, Sy Seashore 577.51 Y. Gardening to attract 101 ways to help birds 2006 Erickson, Laura. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA Birds - Conservation. 639.978 birds. Sharpe, Grant, and Wenonah University of Wisconsin Press, 101 wildflowers of Arcadia National Park 1963 581.769909741 Sharpe Madison, WI 1300 real and fanciful animals : from Animals, Mythical in 1998 Merian, Matthaus Dover Publications, Mineola, NY Animals in art 769.432 seventeenth-century engravings. -

Volume 91 Issue 2 Mar-Apr 2014

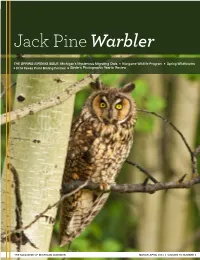

Jack Pine Warbler THE SPRING BIRDING ISSUE: Michigan’s Mysterious Migrating Owls Nongame Wildlife Program Spring Wildflowers 2014 Tawas Point Birding Festival Birder’s Photographic Year in Review THE MAGAZINE OF MICHIGAN AUDUBON MARCH-APRIL 2014 | VOLUME 91 NUMBER 2 Cover Photo Long-eared Owl Photographer: Chris Reinhold | [email protected] One day, while taking a drive to a place I normally shoot many hawks and eagles, I came across this Long-eared Owl perched on a fence post. I had heard a number of screeches coming from the CONTACT US area where the owl was hanging out and hunting, so I figured it had By mail: a family of young owls, which it did (four of them). I kept going back PO Box 15249 day after day; I think the owl finally got used to me because I was Lansing, MI 48901 able to get close enough to capture this shot and many others (find them at www.wildartphotography.ca). This image was taken at 1/100 By visiting: sec at f6.3, 500mm focal length, ISO 400 using a stabilized lens and Bengel Wildlife Center Tripod. Gear was a Canon 7D and Sigma 150-500mm lens. 6380 Drumheller Road Bath, MI 48808 Phone 517-641-4277 Fax 517-641-4279 Mon.–Fri. 9 AM–5 PM Contents EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Jonathan E. Lutz [email protected] Features Columns Departments STAFF Tom Funke 2 8 1 Conservation Director Michigan's Mysterious A Fine Kettle of Hawks Executive Director’s Letter [email protected] Migratory Owls 2013 Spring Raptor Migration Wendy Tatar 3 Program Coordinator 4 9 Calendar [email protected] Michigan’s Nongame Book Review Wildlife Program Used Books Help Birds 13 Mallory King Announcements Marketing and Communications Coordinator 7 10 New Member List [email protected] Warblers & New Waves in Chapter Spotlight Birding & 2014 Tawas Point Oakland Audubon Society Michael Caterino Birding Festival Membership Assistant 11 [email protected] Spring Wildflowers EDITOR Ephemeral: n. -

A Survey of Odonata of the Patoka River National Wildlife Refuge and Management Area

2012. Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science 121(1):54–61 A SURVEY OF ODONATA OF THE PATOKA RIVER NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE AND MANAGEMENT AREA Donald L. Batema* and Amanda Bellian: Department of Chemistry, Environmental Studies Program, University of Evansville, 1800 Lincoln Avenue, Evansville, IN 47722 USA Lindsey Landowski: Mingo National Wildlife Refuge, Puxico, MO. 63960 USA ABSTRACT. The Patoka River National Wildlife Refuge and Management Area (hereafter Patoka River Refuge or the Refuge) represents one of the largest intact bottomland hardwood forests in southern Indiana, with meandering oxbows, marshes, ponds, managed moist-soil units, and constructed wetlands that provide diverse and suitable habitat for wildlife. Refuge personnel strive to protect, restore, and manage this bottomland hardwood ecosystem and associated habitats for a variety of wildlife. The Patoka River National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan (CCP) lists many species of management priority (McCoy 2008), but Odonata are not included, even though they are known to occur on the Refuge. The absence of Odonata from the CCP is the result of lack of information about this ecologically important group of organisms. Therefore, we conducted a survey, from May to October 2009, to document their presence, with special attention being paid to rare, threatened, and endangered species. A total of 43 dragonfly and damselfly species were collected and identified. No threatened or endangered species were found on the Refuge, but three species were found that are considered imperiled in Indiana based on Nature Serve Ranks (Stein 2002). Additionally, 19 new odonate records were documented for Pike County, Indiana. The results of this survey will be used by Refuge personnel to assist in management decisions and to help establish priorities for the Patoka River Refuge activities and land acquisition goals. -

BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis Mcintosh

COM . TOCK S HUTTER © S © BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis McIntosh For passionate birdwatcher Sandy Komito of over age 16 say they actively observe and try to iden- Fair Lawn, New Jersey, 1998 was a big year. In a tify birds, although few go to the extremes Komito tight competition with two fellow birders to see as did. About 88 percent are content to enjoy bird many species as possible in a single year, Komito watching in their own backyards or neighborhoods. traveled 270,000 miles, crisscrossing North Amer- More avid participants plan vacations around ica and voyaging far out to sea to locate rare and their hobby and sometimes travel long distances to elusive birds. In the end, he set a North American view a rare species and add it to their lifelong list of record of 748 species, topping his own previous birds spotted. Many birdwatchers, both casual and record of 726, which had stood for 11 years. serious, also function as citizen scientists, provid- Komito and his fellow competitors are not alone ing valuable data to help scientists monitor bird in their love of birds. According to a U.S. Fish and populations and create management guidelines to Wildlife Service survey, about one in five Americans protect species in decline. 36 2 0 1 4 N UMBER 1 | E NGLISH T E ACHING F ORUM Birding Basics The origins of bird watching in the United States date back to the late 1800s when conserva- tionists became concerned about the hunting of birds to supply feathers for the fashion industry. -

Describing Visuality and Imagining Vision in Eleventh-Century Chinese Painters’ Biographies 87

DOI: 10.6503/THJCS.202103_51(1).0003 Learning How to See Again: Describing Visuality and Imagining Vision in ∗ Eleventh-Century Chinese Painters’ Biographies Ari Daniel Levine∗∗ Department of History University of Georgia ABSTRACT This article seeks to reconstruct the implicit epistemic assumptions that shaped descriptions of visuality and vision in three mid-eleventh-century collections of painters’ biographies—Liu Daochun’s 劉道醇 (fl. 1050-1060) Shengchao minghua ping 聖朝名畫評 (c. 1057) and Wudai minghua buyi 五代名畫補遺 (1059), and Guo Ruoxu’s 郭若虛 (c. 1041-c. 1098) Tuhua jianwen zhi 圖畫見聞志 (c. 1074). Through a close reading of these texts, which record how these two Northern Song literati viewed and recalled paintings both lost and extant, this article will explain how they imagined the processes of visual perception and memory to function. Liu and Guo’s written descriptions of the experiences of observers viewing paintings, and of painters viewing and painting pictorial subject matter, provide evidence of two distinctive understandings of visuality that involved both optical visualization in the present and mentalized visions in memory. For Liu and Guo, writing about viewing paintings re-activated the experience of seeing for themselves, which involved reconstituting images from their own visual memories, or describing other observers’ ∗ I presented earlier versions of this article at the Second Conference on Middle-Period China at Leiden University in September 2017, at the Karl Jaspers Centre for Transcultural Studies at Heidelberg University in June 2019, and at the International Conference “New Perspectives on Song Sources: Reflecting upon the Past and Looking to the Future” at National Tsing Hua University in December 2019. -

Friends of the San Pedro River Roundup

Friends of the San Pedro River Roundup Winter 2014 In This Issue: Bioblitz... Lectures... Film Festival... Executive Director’s Report... Festival of Arts... BLM Acting Director’s Visit... Archeology & Heritage Month... Dark Skies Position... Ron Beck’s Big Year... Christmas Bird Count Results... Trees along the 19th-Century River... Brunckow’s Cabin Rehab... EOP Leaders Sought... Walkway Bricks... Operations Committee... Members ... Calendar ... Contacts Save the Date! The morning of April 26, FSPR will hold a Bioblitz (an inventory of the flora and fauna) at various locations in SPRNCA. Stay tuned for details in the coming weeks. FSPR Lectures February & March 20 JoinPawlowski, us on Thursday, Water Sentinels February Program 20 at 7 Coordinatorpm at the Sierra for the Vista Grand Ranger Canyon District Chapter Office, of 4070the Sierra East AvenidaClub, will Saracino, Hereford, for a lecture by Becky Orozco on the Chiracahua Apache. Then, on March 20, Steve discuss ecology and conservation of the San Pedro River; current threats; and the conservation work of the Sentinels within SPRNCA. Learn how to use citizen science, “hands-on” conservation, and advocacy to shape a more-sustainable future for one of the Southwest’s most ecologically significant rivers. Second Annual Wild & Scenic Film Festival March 13 & 14 The Friends have been invited to host our second Wild & Scenic Film Festival as part of the 12th annual event that showcases North America’s premier collection of short films on the environment. We have selected 13 films for the evening program for adults that are relevant to many of the issues facing the Southwest. Some will make you smile, some may get you angry, others will have you amazed, but hopefully, all will motivate you to get involved. -

The Oak Treehopper.Pdf

ENTOMOLOGY CIRCULAR No.57 FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FEBRUARY 1967 DIVISION OF PLANT INDUSTRY THE OAK TREEHOPPER, PLATYCOTISVITTATA (FABRICIUS) 1 (HOMOPTERA: MEMBRACIDAE) F. w. MEAD I NTROOUCTlON: THE OAK TREEHOPPER IS FAIRLY COMMON ON DECIDUOUS AND EVERGREEN OAKS, QUERCUS SPP., WHERE IT IS SOMETIMES SUFFICIENTLY ABUNDANT TO CAUSE CONCERN TO OWNERS OF VALUABLE SHADE TREES. IN FLORIDA WE HAVE REPORTS OF PROFESSIONAL SPRAYMEN BEING HIRED TO CONTROL THIS PEST. HOWEVER, DAMAGE BY A COLONY OF THIS SPECIES OF TREEHOPPER IS MINOR AND ESSENTIALLY CONFINED TO SMALL OVIPOSITION SCARS IN TWIGS. THiS CONTRASTS WITH THE CLOSELY RELATED THORN BUG, !JMBONIA CRASSICORNIS (A. &: S.) , WHICH CAN, WHEN ABUNDANT, CAUSE CONSIDERABLE DIEBACK OR EVE~ DEATH OF SMALL TREES. ""- ~ """""0' 0. ~ """, '."" ~ 6-},. , FIG. FiG. 2. NYMPH. 7X LEFT. f1.rnIDA ~ DISTRIBUTION OF 7 PLATYCOTJS VITTATA. ... -A'" FIG. 3. ADULT .E. VITTATA VAR. fSAGITTAn'. 7x DISTRIBUTION: FUNKHOUSER (1951) GIVES THE DISTRIBUTION AS BRAZIL, MEXICO, AND UN!TED STATES. THiS SPECIES ALSO HAS BEEN REPORTED FROM VANCOUVER ISLAND, CANADA. THE RECORDED DISTRIBUTION IN THE UNITED STATES IS PRIMARILY IN THE STATES THAT FORM A BROAD U-SHAPED CURVE FROM PENNSYLVANIA AND NEW JERSEY SOUTH THROUGH THE CAROLINAS AND GEORGIA TO FLORIDA, THEN WEST TO MISSISSIPPi. TEXAS, ARIZONA, CALIFORNIA, AND NORTH TO OREGON (AND VANCOUVER) WHERE THE COASTAL CLIMATE IS MODERATE. INTERIOR RECORDS INCLUDE OHIO, ILLiNOiS. TENNESSEE, AND WESTERN NORTH CAROLINA, BUT IN GENERAL, THERE IS A SCARCITY OF RECORDS FROM THE GREAT HEARTLAND AREAS OF THE UNITED STATES. THE 40TH PARALLEL SERVES AS AN APPROXiMATE NORTHERN RANGE LIMIT WITH FEW EXCEPTiONS. THE FLORIDA DISTRIBUTION IS INDICATED IN FiG. -

Bushhopper Stalk-Eyed Fly Coconut Crab Periodical Cicada

PIOTR NASKRECKI PHOTO BANNERS HANGING IN CHANGING EXHIBIT GALLERY Bushhopper Stalk-Eyed Fly Phymateus viridipes Diasemopsis fasciata Gorongosa National Park, Mozambique Gorongosa National Park, Mozambique A nymph of the bushhopper from Mozambique Like antlers on a deer’s head, the long can afford to be slow and conspicuous thanks eyestalks on this fly’s head are used in maleto- to the toxins in its body. These insects feed male combat, allowing the individual with on plants rich in poisonous metabolites, the largest stalks to win access to females including some that can cause heart failure, so most predators avoid them. Coconut Crab Periodical Cicada Birgus latro Magicicada septendecim Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands Annandale, Virginia The coconut crab is not just another land Periodical cicadas spend seventeen years crab; it is the largest living terrestrial underground, feeding on the roots of plants. invertebrate, reaching a weight of nine After that time they all emerge at the same pounds and a leg span of over three feet. time, causing consternation in people and Their lifespan is equally impressive, and the a feeding frenzy in birds. A newly emerged largest individuals are believed to be forty to (eclosed) periodical cicada is almost snow sixty years old. white, but within a couple of hours its body darkens and the exoskeleton becomes hard. BIG BUGS • Dec. 31, 2015 - April 17, 2016 Virginia Living Museum • 524 J. Clyde Morris Blvd. • Newport News, VA 23601 • 757-595-1900 • thevlm.org PIOTR NASKRECKI PHOTO BANNERS HANGING IN CHANGING EXHIBIT GALLERY Dung Beetles Lappet Moth Kheper aegyptiorum Chrysopsyche lutulenta Gorongosa National Park, Mozambique Gorongosa National Park, Mozambique Dung beetles are very important members of At the beginning of the dry season in Savanna communities.