Solid Waste Management for Kathmandu Metropolitan City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A/HRC/13/39/Add.1 General Assembly

United Nations A/HRC/13/39/Add.1 General Assembly Distr.: General 25 February 2010 English/French/Spanish only Human Rights Council Thirteenth session Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, Manfred Nowak Addendum Summary of information, including individual cases, transmitted to Governments and replies received* * The present document is being circulated in the languages of submission only as it greatly exceeds the page limitations currently imposed by the relevant General Assembly resolutions. GE.10-11514 A/HRC/13/39/Add.1 Contents Paragraphs Page List of abbreviations......................................................................................................................... 5 I. Introduction............................................................................................................. 1–5 6 II. Summary of allegations transmitted and replies received....................................... 1–305 7 Algeria ............................................................................................................ 1 7 Angola ............................................................................................................ 2 7 Argentina ........................................................................................................ 3 8 Australia......................................................................................................... -

Nepal Human Rights Year Book 2021 (ENGLISH EDITION) (This Report Covers the Period - January to December 2020)

Nepal Human Rights Year Book 2021 (ENGLISH EDITION) (This Report Covers the Period - January to December 2020) Editor-In-Chief Shree Ram Bajagain Editor Aarya Adhikari Editorial Team Govinda Prasad Tripathee Ramesh Prasad Timalsina Data Analyst Anuj KC Cover/Graphic Designer Gita Mali For Human Rights and Social Justice Informal Sector Service Centre (INSEC) Nagarjun Municipality-10, Syuchatar, Kathmandu POBox : 2726, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: +977-1-5218770 Fax:+977-1-5218251 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.insec.org.np; www.inseconline.org All materials published in this book may be used with due acknowledgement. First Edition 1000 Copies February 19, 2021 © Informal Sector Service Centre (INSEC) ISBN: 978-9937-9239-5-8 Printed at Dream Graphic Press Kathmandu Contents Acknowledgement Acronyms and Abbreviations Foreword CHAPTERS Chapter 1 Situation of Human Rights in 2020: Overall Assessment Accountability Towards Commitment 1 Review of the Social and Political Issues Raised in the Last 29 Years of Nepal Human Rights Year Book 25 Chapter 2 State and Human Rights Chapter 2.1 Judiciary 37 Chapter 2.2 Executive 47 Chapter 2.3 Legislature 57 Chapter 3 Study Report 3.1 Status of Implementation of the Labor Act at Tea Gardens of Province 1 69 3.2 Witchcraft, an Evil Practice: Continuation of Violence against Women 73 3.3 Natural Disasters in Sindhupalchok and Their Effects on Economic and Social Rights 78 3.4 Problems and Challenges of Sugarcane Farmers 82 3.5 Child Marriage and Violations of Child Rights in Karnali Province 88 36 Socio-economic -

COVID19 Reporting of Naukunda RM, Rasuwa.Pdf

स्थानिय तहको विवरण प्रदेश जिल्ला स्थानिय तहको नाम Bagmati Rasuwa Naukunda Rural Mun सूचना प्रविधि अधिकृत पद नाम सम्पर्क नं. वडा ठेगाना कैफियत सूचना प्रविधि अधिकृतसुमित कुमार संग्रौला 9823290882 ६ गोसाईकुण्ड गाउँपालिका जिम्मेवार पदाधिकारीहरू क्र.स. पद नाम सम्पर्क नं. वडा ठेगाना कैफियत 1 प्रमुख प्रशासकीय अधिकृतनवदीप राई 9807365365 १३ विराटनगर, मोरङ 2 सामजिक विकास/ स्वास्थ्यअण प्रसाद शाखा पौडेल प्रमुख 9818162060 ५ शुभ-कालिका गाउँपालिका, रसुवा 3 सूचना अधिकारी डबल बहादुर वि.के 9804669795 ५ धनगढी उपमहानगरपालिका, कालिका 4 अन्य नितेश कुमार यादव 9816810792 ६ पिपरा गाउँपालिका, महोत्तरी 5 6 n विपद व्यवस्थापनमा सहयोगी संस्थाहरू क्र.स. प्रकार नाम सम्पर्क नं. वडा ठेगाना कैफियत 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 n ारेाइन केको ववरण ID ारेाइन केको नाम वडा ठेगाना केन्द्रको सम्पर्क व्यक्तिसम्पर्क नं. भवनको प्रकार बनाउने निकाय वारेटाइन केको मता Geo Location (Lat, Long) Q1 गौतम बुद्ध मा.वि क्वारेन्टाइन स्थल ३ फाम्चेत नितेश कुमार यादव 9816810792 विध्यालय अन्य (वेड संया) 10 28.006129636870693,85.27118702477858 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q5 Q6 Q7 Q8 Q9 Q10 Q11 Qn भारत लगायत विदेशबाट आएका व्यक्तिहरूको विवरण अधारभूत विवरण ारेाइन/अताल रफर वा घर पठाईएको ववरण विदेशबाट आएको हो भने मात्र कैिफयत ID नाम, थर लिङ्ग उमेर (वर्ष) वडा ठेगाना सम्पर्क नं. -

NEPAL: Preparing the Secondary Towns Integrated Urban

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 36188 November 2008 NEPAL: Preparing the Secondary Towns Integrated Urban Environmental Improvement Project (Financed by the: Japan Special Fund and the Netherlands Trust Fund for the Water Financing Partnership Facility) Prepared by: Padeco Co. Ltd. in association with Metcon Consultants, Nepal Tokyo, Japan For Department of Urban Development and Building Construction This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. TA 7182-NEP PREPARING THE SECONDARY TOWNS INTEGRATED URBAN ENVIRONMENTAL IMPROVEMENT PROJECT Volume 1: MAIN REPORT in association with KNOWLEDGE SUMMARY 1 The Government and the Asian Development Bank agreed to prepare the Secondary Towns Integrated Urban Environmental Improvement Project (STIUEIP). They agreed that STIUEIP should support the goal of improved quality of life and higher economic growth in secondary towns of Nepal. The outcome of the project preparation work is a report in 19 volumes. 2 This first volume explains the rationale for the project and the selection of three towns for the project. The rationale for STIUEIP is the rapid growth of towns outside the Kathmandu valley, the service deficiencies in these towns, the deteriorating environment in them, especially the larger urban ones, the importance of urban centers to promote development in the regions of Nepal, and the Government’s commitments to devolution and inclusive development. 3 STIUEIP will support the objectives of the National Urban Policy: to develop regional economic centres, to create clean, safe and developed urban environments, and to improve urban management capacity. -

Madan Bhandari Highway

Report on Environmental, Social and Economic Impacts of Madan Bhandari Highway DECEMBER 17, 2019 NEFEJ Lalitpur Executive Summary The report of the eastern section of Madan Bhandari Highway was prepared on the basis of Hetauda-Sindhuli-Gaighat-Basaha-Chatara 371 km field study, discussion with the locals and the opinion of experts and reports. •During 2050's,Udaypur, Sindhuli and MakwanpurVillage Coordination Committee opened track and constructed 3 meters width road in their respective districts with an aim of linking inner Madhesh with their respective headquarters. In the background of the first Madhesh Movement, the road department started work on the concept of alternative roads. Initially, the double lane road was planned for an alternative highway of about 7 meters width. The construction of the four-lane highway under the plan of national pride began after the formation of a new government of the federal Nepal on the backdrop of the 2072 blockade and the Madhesh movement. The Construction of Highway was enunciated without the preparation of an Environmental Impact Assessment Report despite the fact that it required EIA before the implementation of the big physical plan of long-term importance. Only the paper works were done on the study and design of the alternative highway concept. The required reports and construction laws were abolished from the psychology that strong reporting like EIA could be a hindrance to the roads being constructed through sensitive terrain like Chure (Siwalik). • During the widening of the roads, 8 thousand 2 hundred and 55 different trees of community forest of Makwanpur, Sindhuli and Udaypur districtsare cut. -

BIRATNAGAR, 18–20 March 2014 Prepared by ADB Consultant Team

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 44140 Date: March 2014 TA 7566-REG: Strengthening and Use of Country Safeguard Systems Subproject: Strengthening Involuntary Resettlement Safeguard Systems (Nepal) CAPACITY ENHANCEMENT TRAINING ON SOCIAL SAFEGUARDS SYSTEM BIRATNAGAR, 18–20 March 2014 Prepared by ADB Consultant Team This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. Training Report Capacity Enhancement Training On Social Safeguards System. 18-20 March 201 Biratnagar TA 7566 REG: Strengthening and Use of Country Safeguards System. NEP Subproject: Strengthening Involuntary Resettlement Safeguard Systems in Nepal niri CET Report Biratnagar 18-20-3-014 – Table of Contents 1 Background: ............................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1. Objectives of the training ................................................................................................................... 4 1.2. Training Schedule: .............................................................................................................................. 4 2. Commencement of the training ................................................................................................................ 4 2.1.Output of the day: ............................................................................................................................. -

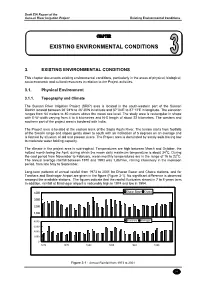

Existing Environmental Conditions

Draft EIA Report of the Sunsari River Irrigation Project Existing Environmental Conditions CHAPTER EXISTING ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS 3. EXISTING ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS This chapter documents existing environmental conditions, particularly in the areas of physical, biological, socio-economic and cultural resources in relation to the Project activities. 3.1. Physical Environment 3.1.1. Topography and Climate The Sunsari River Irrigation Project (SRIP) area is located in the south-western part of the Sunsari District located between 26°24′N to 26°30′N in latitude and 87°04′E to 87°12′E in longitude. The elevation ranges from 64 meters to 80 meters above the mean sea level. The study area is rectangular in shape with E-W width varying from 4 to 8 kilometres and N-S length of about 22 kilometres. The western and southern part of the project area is bordered with India. The Project area is located at the eastern bank of the Sapta Koshi River. The terrain starts from foothills of the Siwalik range and slopes gently down to south with an inclination of 5 degrees on an average and is formed by alluvium of old and present rivers. The Project area is dominated by sandy soils having low to moderate water holding capacity. The climate in the project area is sub-tropical. Temperatures are high between March and October, the hottest month being the April, during which the mean daily maximum temperature is about 340C. During the cool period from November to February, mean monthly temperatures are in the range of 16 to 220C. The annual average rainfall between 1970 and 1993 was 1,867mm, raining intensively in the monsoon period, from late May to September. -

FINAL REPORT.Pdf

Government of Nepal Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development Ilam Municipality Ilam Preparation of GIS based Digital Base Urban Map Upgrade of Ilam Municipality, Ilam Final Report Submitted By: JV Grid Consultant Pvt. Ltd, Galaxy Pvt. Ltd and ECN Consultancy Pvt. Ltd June 2017 Government of Nepal Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development Ilam Municipality Ilam Preparation of GIS based Digital Base Urban Map Upgrade of Ilam Municipality, Ilam Final Report MUNICIPALITY PROFILE Submitted By: JV Grid Consultant Pvt. Ltd, Galaxy Pvt. Ltd and ECN Consultancy Pvt. Ltd June 2017 Table of Content Contents Page No. CHAPTER - I ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 NAMING AND ORIGIN............................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 LOCATION.............................................................................................................................................. 1 1.3 SETTLEMENTS AND ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS ......................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER - II.................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 PHYSIOGRAPHY......................................................................................................................................4 2.2 GEOLOGY/GEOMORPHOLOGY -

Biratnagar Airport

BIRATNAGAR AIRPORT Brief Description Biratnagar Airport is located at north of Biratnagar Bazaar, Morang District of Province No. 1. and serves as a hub airport. This airport is the first certified aerodrome among domestic / Hub airports of Nepal and second after Tribhuvan International Airport. This airport is considered as the second busiest domestic airport in terms of passengers' movement after Pokhara airport. General Information Name BIRATNAGAR Location Indicator VNVT IATA Code BIR Aerodrome Reference Code 3C Aerodrome Reference Point 262903 N/0871552 E Province/District 1(One)/Morang Distance and Direction from City 5 Km North West Elevation 74.972 m. /245.94 ft. Off: 977-21461424 Tower: 977-21461641 Contact Fax: 977-21460155 AFS: VNVTYDYX E-mail: [email protected] Night Operation Facilities Available 16th Feb to 15th Nov 0600LT-1845LT Operation Hours 16th Nov to 15th Feb 0630LT-1800LT Status In Operation Year of Start of Operation 6 July, 1958 Serviceability All Weather Land Approx. 773698.99 m2 Re-fueling Facility Yes, by Nepal Oil Corporation Service Control Service Instrumental Flight Rule(IFR) Type of Traffic Permitted Visual Flight Rule (VFR) ATR72, CRJ200/700, DHC8, MA60, ATR42, JS-41, B190, Type of Aircraft D228, DHC6, L410, Y12 Buddha Air, Yeti Airlines, Shree Airlines, Nepal Airlines, Schedule Operating Airlines Saurya Airlines Schedule Connectivity Tumlingtar, Bhojpur, Kathmandu RFF Category V Infrastructure Condition Airside Runway Type of surface Bituminous Paved (Asphalt Concrete) Runway Dimension 1500 -

District Transport Master Plan (DTMP)

Government of Nepal District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development Department of Local Infrastructure Development and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR) District Development Committee, Morang February 2013 Prepared by the District Technical Office (DTO) for Morang with Technical Assistance from the Department of Local Infrastructure and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR), Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development and grant supported by DFID i FOREWORD It is my great pleasure to introduce this District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) of Morang district especially for district road core network (DRCN). I believe that this document will be helpful in backstopping to Rural Transport Infrastructure Sector Wide Approach (RTI SWAp) through sustainable planning, resources mobilization, implementation and monitoring of the rural road sub-sector development. The document is anticipated to generate substantial employment opportunities for rural people through increased and reliable accessibility in on- farm and off-farm livelihood diversification, commercialization and industrialization of agriculture sector. In this context, rural road sector will play a fundamental role to strengthen and promote overall economic growth of this district through established and improved year round transport services reinforcing intra and inter-district linkages . Therefore, it is most crucial in executing rural road networks in a planned way as per the District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) by considering the framework of available resources in DDC comprising both internal and external sources. Viewing these aspects, DDC Morang has prepared the DTMP by focusing most of the available resources into upgrading and maintenance of the existing road networks. This document is also been assumed to be helpful to show the district road situations to the donor agencies through central government towards generating needy resources through basket fund approach. -

Annual Report Submitted to USAID So the Details of Those Activities Are Not Reported Here

From Combatants to Peacemakers Program Project Final Report October, 2015 to March 31, 2017 Award No: AID-367-F-15-00002 Under USAID/DCHA/CMM APS-OAA-14-000003 Submitted to: United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Democracy and Governance Office Maharajgunj, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: +977-01-42340000 Submitted by: Forum for Protection of Public Interest (Pro Public) Gautambuddha Marg, Anamnagar P.O.Box: 14307 Telephone: +977-01-4268681, 4265023 Fax: +977-01-4268022 1 Disclaimer: All these activities were made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of Pro Public and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. 2 Abbreviations BC Brahmin Chhetri CBO Community Based Organization CDO Chief District Officer CPN Communist Party of Nepal CSO Civil Society Organization DDC District Development Committee DF Dialogue facilitation ECs Ex-Combatants FGD Focus Group Discussion GESI Gender and Social Inclusion GIZ Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH KII Key Informant Interview LPC Local Peace Committee NC Nepali Congress NPTF Nepal Peace Trust Fund OCA Organizational Capacity Assessment OPI Organizational Performance Index PLA People Liberation Army Pro Public Forum for the Protection of Public Interest SDG Social Dialogue Group STPP Strengthening the Peace Process UCPN United Communist Party of Nepal UML United Marxist Leninist UNDP United Nations Development Program USAID United States Agency for International Development VDC Village Development Committee WCF Ward Citizen Forum 3 Acknowledgement This project completion report covers the overall implementation of the USAID-funded Combatants to Peacemakers (C2P) project (October 2015 to March 2017). -

Focused COVID-19 Media Monitoring, Nepal

Focused COVID-19 Media Monitoring, Nepal Focused COVID-19 Media Monitoring Nepal1 -Sharpening the COVID-19 Response through Communications Intelligence Date: May 18, 2021 Kathmandu, Nepal EMERGING THEME(S) • Nepal reports 9,198 new COVID-19 cases, 214 fatalities on May 16; recoveries are rising — 6,648 on May 16, highest till date; infection rate in Kathmandu Valley, some urban centers have declined, but too early to say if infection has decreased nationwide as virus has spread to rural areas, according to Health Ministry • Weak health infrastructure in villages of Nepal could mean a looming disaster as COVID-19 infections could peak this week • Government to bring new ordinance to control COVID-19 pandemic; scrap Epidemiology and Disease Control Division and set up Center of Disease Control proposed; government hospitals in Kathmandu start COVID-OPD service • Government starts procurement process of 2,000,000 doses of Vero Cell from China; first 1,000,000 doses to arrive by first week of June • Sudurpaschim’s COVID-19-infected are the losers between the ego clash between federal and provincial governments; Province’s Butwal, Nepalgunj and Dhangadi have become COVID-19 hotspots • Province 1 facing shortage of COVID-19 test kits, reagents; Antigen Tests halted • COVID-19-infected have become more panicky, lost their strong willpower this time around, observe healthcare workers • Supreme Court has issued mandamus order to government to put an end to the dismal COVID-19 situation; SC’s Bar Association has slammed the government for negligence and inefficiency in its handling of COVID-19 pandemic that has resulted in loss of many lives • Around 3,000,000 laborers have lost their livelihood as a result of the imposition of prohibitory orders 1 This intelligence is tracked through manually monitoring national print, digital and online media through a representative sample selection, and consultations with media persons and media influencers.