ERASMUS' THEORY of SELF-DEFENCE Controversies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scenario Book 1

Here I Stand SCENARIO BOOK 1 SCENARIO BOOK T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S ABOUT THIS BOOK ......................................................... 2 Controlling 2 Powers ........................................................... 6 GETTING STARTED ......................................................... 2 Domination Victory ............................................................. 6 SCENARIOS ....................................................................... 2 PLAY-BY-EMAIL TIPS ...................................................... 6 Setup Guidelines .................................................................. 2 Interruptions to Play ............................................................ 6 1517 Scenario ...................................................................... 3 Response Card Play ............................................................. 7 1532 Scenario ...................................................................... 4 DESIGNER’S NOTES ........................................................ 7 Tournament Scenario ........................................................... 5 EXTENDED EXAMPLE OF PLAY................................... 8 SETTING YOUR OWN TIME LIMIT ............................... 6 THE GAME AS HISTORY................................................. 11 GAMES WITH 3 TO 5 PLAYERS ..................................... 6 CHARACTERS OF THE REFORMATION ...................... 15 Configurations ..................................................................... 6 EVENTS OF THE REFORMATION -

![List 3-2016 Accademia Della Crusca – Aldine Device 1) [BARDI, Giovanni (1534-1612)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5354/list-3-2016-accademia-della-crusca-aldine-device-1-bardi-giovanni-1534-1612-465354.webp)

List 3-2016 Accademia Della Crusca – Aldine Device 1) [BARDI, Giovanni (1534-1612)]

LIST 3-2016 ACCADEMIA DELLA CRUSCA – ALDINE DEVICE 1) [BARDI, Giovanni (1534-1612)]. Ristretto delle grandeze di Roma al tempo della Repub. e de gl’Imperadori. Tratto con breve e distinto modo dal Lipsio e altri autori antichi. Dell’Incruscato Academico della Crusca. Trattato utile e dilettevole a tutti li studiosi delle cose antiche de’ Romani. Posto in luce per Gio. Agnolo Ruffinelli. Roma, Bartolomeo Bonfadino [for Giovanni Angelo Ruffinelli], 1600. 8vo (155x98 mm); later cardboards; (16), 124, (2) pp. Lacking the last blank leaf. On the front pastedown and flyleaf engraved bookplates of Francesco Ricciardi de Vernaccia, Baron Landau, and G. Lizzani. On the title-page stamp of the Galletti Library, manuscript ownership’s in- scription (“Fran.co Casti”) at the bottom and manuscript initials “CR” on top. Ruffinelli’s device on the title-page. Some foxing and browning, but a good copy. FIRST AND ONLY EDITION of this guide of ancient Rome, mainly based on Iustus Lispius. The book was edited by Giovanni Angelo Ruffinelli and by him dedicated to Agostino Pallavicino. Ruff- inelli, who commissioned his editions to the main Roman typographers of the time, used as device the Aldine anchor and dolphin without the motto (cf. Il libro italiano del Cinquec- ento: produzione e commercio. Catalogo della mostra Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Roma 20 ottobre - 16 dicembre 1989, Rome, 1989, p. 119). Giovanni Maria Bardi, Count of Vernio, here dis- guised under the name of ‘Incruscato’, as he was called in the Accademia della Crusca, was born into a noble and rich family. He undertook the military career, participating to the war of Siena (1553-54), the defense of Malta against the Turks (1565) and the expedition against the Turks in Hun- gary (1594). -

Virtues and Vices to Luke E

CATHOLIC CHRISTIANITY THE LUKE E. HART SERIES How Catholics Live Section 4: Virtues and Vices To Luke E. Hart, exemplary evangelizer and Supreme Knight from 1953-64, the Knights of Columbus dedicates this Series with affection and gratitude. The Knights of Columbus presents The Luke E. Hart Series Basic Elements of the Catholic Faith VIRTUES AND VICES PART THREE• SECTION FOUR OF CATHOLIC CHRISTIANITY What does a Catholic believe? How does a Catholic worship? How does a Catholic live? Based on the Catechism of the Catholic Church by Peter Kreeft General Editor Father John A. Farren, O.P. Catholic Information Service Knights of Columbus Supreme Council Nihil obstat: Reverend Alfred McBride, O.Praem. Imprimatur: Bernard Cardinal Law December 19, 2000 The Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur are official declarations that a book or pamphlet is free of doctrinal or moral error. No implication is contained therein that those who have granted the Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur agree with the contents, opinions or statements expressed. Copyright © 2001-2021 by Knights of Columbus Supreme Council All rights reserved. English translation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church for the United States of America copyright ©1994, United States Catholic Conference, Inc. – Libreria Editrice Vaticana. English translation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church: Modifications from the Editio Typica copyright © 1997, United States Catholic Conference, Inc. – Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Scripture quotations contained herein are adapted from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1946, 1952, 1971, and the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1989, by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America, and are used by permission. -

Philip Melanchthon in the Writings of His Polish Contemporaries

ODRODZENIE I REFORMACJA W POLSCE ■ SI 2017 ■ PL ISSN 0029-8514 Janusz Tazbir Philip Melanchthon in the Writings of his Polish Contemporaries Over thirty years ago Oskar Bartel, a distinguished scholar of the history of the Polish Reformation, bemoaned how little was known about the relations between preceptor Germaniae and the movement. In an article about the familiarity with Melanchthon, both as person and his oeuvre, in Poland, Bartel wrote: “wir besitzen einige Werke, meist Broschüren über Luther, Calvin, sogar Hus und Zwingli, aber ich habe keine über Melanchton gefunden”.1 Bartel’s article provided a recapitulation, if somewhat incomplete, of the state of research at the time, and essentially stopped at the death of the Reformer. There- fore, in this study I would like to point to the results of the last thirty years of research, on the one hand, and highlight the post-mortem impact of Melanchthon’s writings and the reflection of his person in the memories of the next generations, on the other. The new information about the contacts Melanchthon had with Poland that has come to light since the 1960s is scattered across a number of articles or monographs; there is to date no separate study devoted to the German Reformer. Only a handful of contributions have been published. No wonder therefore that twenty years after the publication of Bartel’s article, Roman Nir begins his study of corre- spondence between Melanchthon and Krzycki thus: “Relatively little 1 O. Bartel, “Luther und Melanchton in Polen,” in: Luther und Melanchton. Refe rate und Berichte des Zweiten Internationalen Kongress für Lutherforschung, Münster, 8.–13. -

Virtue Theory and the Present Evolution of Thorn Ism

Virtue Theory and the Present Evolution of Thorn ism Romanus Cessario, O.P. Overthepastdecade,aquietrevolutionhasbeengatheringmomen tum in the fields of moral philosophy and Christian ethics. These disciplines are undergoing a decisive shift as duty, obligation, and decision yield their central role in the understanding of the moral life lo the long-neglected concepts of virtue, character, and action. 1 In the En glish-speaking world, Alasdair Macintyre remains the chief spokesman for the effort. It may interest some to learn that several years before he published After Virtue in 1981, the Faculty of the Dominican House of Studies in Washington, D. C., had decided to reinstate instruction in speculative moral theology, especially treating the matter of virtue theory. In the late 1960s, that is, shortly after the conciliar directive Optatam totius, No. 16, urged that the development of moral theology "should be nourished more thoroughly by scriptural teaching," such instruction had been dropped from the curriculum and replaced by courses such as the "Biblical Foundations of Morality." In some respects, we can credit British scholarship within the analytical tradition as providing the impetus toward a contemporary study of the virtues.2 Peter Geach, for instance, renders a complete account of classical virtue theory in his small book, The Virtues (Cam bridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977).3 In this work, the author 1. In The Moral Virtues and Theological Ethics (Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 1991), I provide an overview of the nature of the moral virtues, their relation to the intellectual virtues, the centrality of prudence in the moral life, and the structures of the acquisition and development of virtues. -

Affect and Ascent in the Theology of Bonaventure

The Force of Union: Affect and Ascent in the Theology of Bonaventure The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Davis, Robert. 2012. The Force of Union: Affect and Ascent in the Theology of Bonaventure. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:9385627 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2012 Robert Glenn Davis All rights reserved. iii Amy Hollywood Robert Glenn Davis The Force of Union: Affect and Ascent in the Theology of Bonaventure Abstract The image of love as a burning flame is so widespread in the history of Christian literature as to appear inevitable. But as this dissertation explores, the association of amor with fire played a precise and wide-ranging role in Bonaventure’s understanding of the soul’s motive power--its capacity to love and be united with God, especially as that capacity was demonstrated in an exemplary way through the spiritual ascent and death of St. Francis. In drawing out this association, Bonaventure develops a theory of the soul and its capacity for transformation in union with God that gives specificity to the Christian desire for self-abandonment in God and the annihilation of the soul in union with God. Though Bonaventure does not use the language of the soul coming to nothing, he describes a state of ecstasy or excessus mentis that is possible in this life, but which constitutes the death and transformation of the soul in union with God. -

Johann Tetzel in Order to Pay for Expanding His Authority to the Electorate of Mainz

THE IMAGE OF A FRACTURED CHURCH AT 500 YEARS CURATED BY DR. ARMIN SIEDLECKI FEB 24 - JULY 7, 2017 THE IMAGE OF A FRACTURED CHURCH AT 500 YEARS Five hundred years ago, on October 31, 1517, Martin Luther published his Ninety-Five Theses, a series of statements and proposals about the power of indulgences and the nature of repentance, forgiveness and salvation. Originally intended for academic debate, the document quickly gained popularity, garnering praise and condemnation alike, and is generally seen as the beginning of the Protestant Reformation. This exhibit presents the context of Martin Luther’s Theses, the role of indulgences in sixteenth century religious life and the use of disputations in theological education. Shown also are the early responses to Luther’s theses by both his supporters and his opponents, the impact of Luther’s Reformation, including the iconic legacy of Luther’s actions as well as current attempts by Catholics and Protestants to find common ground. Case 1: Indulgences In Catholic teaching, indulgences do not effect the forgiveness of sins but rather serve to reduce the punishment for sins that have already been forgiven. The sale of indulgences was initially intended to defray the cost of building the Basilica of St. Peter in Rome and was understood as a work of charity, because it provided monetary support for the church. Problems arose when Albert of Brandenburg – a cardinal and archbishop of Magdeburg – began selling indulgences aggressively with the help of Johann Tetzel in order to pay for expanding his authority to the Electorate of Mainz. 2 Albert of Brandenburg, Archbishop of Mainz Unused Indulgence (Leipzig: Melchior Lotter, 1515?) 1 sheet ; 30.2 x 21 cm. -

Aquinas's Doctrine of Moral Virtue and Its Significance for Theories of Facility

AQUINAS'S DOCTRINE OF MORAL VIRTUE AND ITS SIGNIFICANCE FOR THEORIES OF FACILITY RENEE MIRKES, O.S.F. Director, Center for NaProEthics Omaha, Nebraska HOMISTIC COMMENTATORS from the post T Scholastic. era to the modern period generally restricted their discussions of Aquinas's doctrine on the relation ship between the acquired and infused virtues to the question of facility, that is, whether or not each kind of virtue facilitates the acts of the other. R. F. Coerver1 gives 1943 as a cutoff date for contemporary discussion of the question of facility in the infused . virtues. His 1946 dissertation on the topic notes that many theolo gians of his day had discarded the distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic facility and, with the exception of the manuals of Merkelbach (1871-1942) and Herve (1881-1958), "few of the modern theologians devote much space to the interrelation of the acquired and infused moral virtues." 2 'See Rev. Robert Florent Coerver, C.M., The Quality of Facility in the Moral Virtues, The Catholic University of America Studies in Sacred Theology 92 (Washington, D.C.: The Cathqlic University of America, 1946). ' Ibid., 113. A literature search from 1946 to 1994 (The Guide to Catholic Literature, Catholic Periodical and Literature Index, and American Theolo.gical Library Association Index) confirms Coerver's observation. The subject of facility in the moral virtues has not appeared as a topic of theological' investigation since the 1940s. An exception is Romanus Cessario's Moral Virtues and Theological Ethics ([Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1991], introduction, 10), which contains a section on the relationship of the acquired and infused moral virtues. -

The Cardinal and Theological Virtues

LESSON 5 The Cardinal and Theological Virtues BACKGROUND READING We don’t often reflect on the staying power Human or Cardinal Virtues that habits have in our lives. Ancient wisdom The four cardinal virtues are human virtues that tells us that habits become nature. We are what govern our moral choices. They are acquired repeatedly do. If we do something over and over by human effort and perfected by grace. The again, eventually we will do that thing without four cardinal virtues are: prudence, justice, thinking. For example, if a person has chewed temperance, and fortitude. The word cardinal her nails all of her life, then chewing nails comes from a Latin word that means “hinge” becomes an unconscious habit that is difficult or “pivot.” All the other virtues are connected to break. Perhaps harder to cultivate are the to, or hinge upon, the cardinal virtues. Without good habits in our lives. If we regularly take time the cardinal virtues, we are not able to live the to exercise, to say no to extra desserts, to get other virtues. up early to pray, to think affirming thoughts of Prudence “disposes practical reason to others, these too can become habits. discern our true good in every circumstance The Catechism of the Catholic Church and to choose the right means of achieving it” defines virtue as “an habitual and firm (CCC 1806). We must recall that our true good disposition to do the good. It allows the person is always that which will lead us to Heaven, so not only to perform good acts, but also to that perhaps another way of saying this is that give the best of himself. -

Can Augustine Offer Any Insight on Vocation? Megan Devore

“The Labors of our Occupation”: Can Augustine Offer Any Insight on Vocation? Megan DeVore Megan DeVore is Associate Professor of Church History and Early Christian Studies in the Department of Theology, School of Undergraduate Studies at Colorado Christian University, Lakewood, Colorado. She earned her PhD specializing in Early Christianity from the University of Wales Trinity Saint David in the United Kingdom. Dr. DeVore is a member of the North American Patristic Society, the American Society of Church History, the Society of Biblical Literature, the Evangelical Theological Society, and the American Classical League. Around the year 401, a curious incident transpired near Roman Carthage. A cluster of nomadic long-haired monks had recently wandered into the area, causing a stir among locals. These monks took the gospel quite seriously; that is, they lived very literally one part of a gospel, “Consider the birds of the air, for they neither sow, nor reap, nor gather into barns … Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow: they labor not” (Matt 6:26-29). They were apparently not only shunning all physical labor on behalf of medita- tive prayer, but they were also (at least according to Augustine’s depiction of the situation) imposing such unemployment upon others, namely local barbers. In response, Augustine penned a unique pamphlet. It takes the form of a retort, but as it unfolds, a commentary on the dignity and duty of work emerges—manual labor, in itself significant, as well as “the labors of our occupation” (labores occupationem nostrarum) and “labor according to our rank and duty” (pro nostro gradu et officio laborantibus, De Op. -

Methods and Masters: Multilingual Teaching in 16Th-Century Louvain

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by idUS. Depósito de Investigación Universidad de Sevilla METHODS AND MASTERS: MULTILINGUAL TEACHING IN 16TH-CENTURY LOUVAIN http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/LA.2017.i40.13 SWIGGERS, PIERRE CENTRO DE HISTORIOGRAFÍA LINGÜÍSTICA, UNIV. DE LOVAINA (BÉLGICA) Profesor ORCID: 0000-0001-9814-2530 VAN ROOY, RAF CENTRO DE HISTORIOGRAFÍA LINGÜÍSTICA, UNIV. DE LOVAINA (BÉLGICA) Investigador ORCID: 0000-0003-3739-8465 Resumen: En el siglo XVI se hablaban y se practicaban varias lenguas en Flandes, especialmente en la ciudad universitaria de Lovaina y en Amberes, centro económico de los Países Bajos españoles. El multilingüismo que se practicaba era por un lado un multilingüismo ‘vertical’, implicando el estudio de las tres lenguas ‘sagradas’ (hebreo, griego, latín); este tipo de estudio se concretizó con la fundación del Collegium Trilingue de Lovaina (1517). Por otro lado, estaba muy difundido un multilingüismo ‘horizontal’, que implicaba las len- guas vernáculas, como el español, el francés y el italiano; este tipo de multilingüismo se explica por el ascenso de la clase comerciante. La presente contribución analiza la documentación disponible (sobre los maestros de lengua y los instrumentos didácticos) y rastrea los factores contextuales que influían en la enseñanza y el aprendizaje de lenguas extranjeras en Flandes, con particular atención a Lovaina. Palabras clave: Historia de la enseñanza de lenguas: Instrumentos didácticos; Multilingüismo (español, francés, italiano); Flandes; Collegi- um Trilingue de Lovaina; siglo XVI Abstract: In 16th-century Flanders, various languages were spoken and practiced, especially in the university town of Louvain and the city of Antwerp, the economic heart of the Southern Low Countries. -

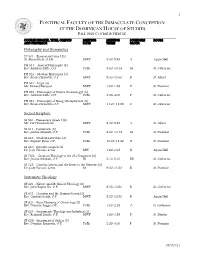

Fall 2021 Course Schedule ______Course Number, Title, Credits Meeting Meeting Schedule Room and Professor Days Times Block

1 PONTIFICAL FACULTY OF THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION AT THE DOMINICAN HOUSE OF STUDIES FALL 2021 COURSE SCHEDULE _____________________________________________________________________________________________ COURSE NUMBER, TITLE, CREDITS MEETING MEETING SCHEDULE ROOM AND PROFESSOR DAYS TIMES BLOCK Philosophy and Humanities LT 501 - Elementary Latin I [3] Sr. Maria Kiely, O.S.B. MWF 8:50-9:45 A Aquin Hall PH 511 - Ancient Philosophy [3] Rev. Ambrose Little, O.P. TuTh 8:50-10:15 M St. Catherine PH 513 - Modern Philosophy [3] Rev. Brian Chrzastek, O.P. MWF 9:55-10:50 B St. Albert PH 521 - Logic [3] Mr. Richard Berquist MWF 1:00-1:55 D St. Dominic PH 523 - Philosophy of Nature (Cosmology) [3] Rev. Ambrose Little, O.P. TuTh 2:35-4:00 P St. Catherine PH 551 - Philosophy of Being (Metaphysics) [3] Rev. Brian Chrzastek, O.P. MWF 11:00-11:55 C St. Catherine Sacred Scripture SS 581 - Elementary Greek I [3] Mr. Carl Vennerstrom MWF 8:50-9:45 A St. Albert SS 611 - Pentateuch [3] Rev. Jordan Schmidt, O.P. TuTh 8:50-10:15 M St. Dominic SS 632 - Wisdom Literature [3] Rev. Stephen Ryan, O.P. TuTh 10:25-11:50 N St. Dominic SS 640 - Synoptic Gospels [3] Dr. Jody Vaccaro Lewis MW 1:00-2:25 H Aquin Hall SS 700L – Creation Theology in the Old Testament [3] Rev. Jordan Schmidt, O.P. W 3:10-5:10 BB St. Catherine SS 765 – Catholic Letters and the Letter to the Hebrews [3] Dr. Jody Vaccaro Lewis M 9:50-11:50 R St.