The Virtue of Equity and the Contemporary World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virtues and Vices to Luke E

CATHOLIC CHRISTIANITY THE LUKE E. HART SERIES How Catholics Live Section 4: Virtues and Vices To Luke E. Hart, exemplary evangelizer and Supreme Knight from 1953-64, the Knights of Columbus dedicates this Series with affection and gratitude. The Knights of Columbus presents The Luke E. Hart Series Basic Elements of the Catholic Faith VIRTUES AND VICES PART THREE• SECTION FOUR OF CATHOLIC CHRISTIANITY What does a Catholic believe? How does a Catholic worship? How does a Catholic live? Based on the Catechism of the Catholic Church by Peter Kreeft General Editor Father John A. Farren, O.P. Catholic Information Service Knights of Columbus Supreme Council Nihil obstat: Reverend Alfred McBride, O.Praem. Imprimatur: Bernard Cardinal Law December 19, 2000 The Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur are official declarations that a book or pamphlet is free of doctrinal or moral error. No implication is contained therein that those who have granted the Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur agree with the contents, opinions or statements expressed. Copyright © 2001-2021 by Knights of Columbus Supreme Council All rights reserved. English translation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church for the United States of America copyright ©1994, United States Catholic Conference, Inc. – Libreria Editrice Vaticana. English translation of the Catechism of the Catholic Church: Modifications from the Editio Typica copyright © 1997, United States Catholic Conference, Inc. – Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Scripture quotations contained herein are adapted from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1946, 1952, 1971, and the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1989, by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America, and are used by permission. -

Virtue Theory and the Present Evolution of Thorn Ism

Virtue Theory and the Present Evolution of Thorn ism Romanus Cessario, O.P. Overthepastdecade,aquietrevolutionhasbeengatheringmomen tum in the fields of moral philosophy and Christian ethics. These disciplines are undergoing a decisive shift as duty, obligation, and decision yield their central role in the understanding of the moral life lo the long-neglected concepts of virtue, character, and action. 1 In the En glish-speaking world, Alasdair Macintyre remains the chief spokesman for the effort. It may interest some to learn that several years before he published After Virtue in 1981, the Faculty of the Dominican House of Studies in Washington, D. C., had decided to reinstate instruction in speculative moral theology, especially treating the matter of virtue theory. In the late 1960s, that is, shortly after the conciliar directive Optatam totius, No. 16, urged that the development of moral theology "should be nourished more thoroughly by scriptural teaching," such instruction had been dropped from the curriculum and replaced by courses such as the "Biblical Foundations of Morality." In some respects, we can credit British scholarship within the analytical tradition as providing the impetus toward a contemporary study of the virtues.2 Peter Geach, for instance, renders a complete account of classical virtue theory in his small book, The Virtues (Cam bridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977).3 In this work, the author 1. In The Moral Virtues and Theological Ethics (Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press, 1991), I provide an overview of the nature of the moral virtues, their relation to the intellectual virtues, the centrality of prudence in the moral life, and the structures of the acquisition and development of virtues. -

Affect and Ascent in the Theology of Bonaventure

The Force of Union: Affect and Ascent in the Theology of Bonaventure The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Davis, Robert. 2012. The Force of Union: Affect and Ascent in the Theology of Bonaventure. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:9385627 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2012 Robert Glenn Davis All rights reserved. iii Amy Hollywood Robert Glenn Davis The Force of Union: Affect and Ascent in the Theology of Bonaventure Abstract The image of love as a burning flame is so widespread in the history of Christian literature as to appear inevitable. But as this dissertation explores, the association of amor with fire played a precise and wide-ranging role in Bonaventure’s understanding of the soul’s motive power--its capacity to love and be united with God, especially as that capacity was demonstrated in an exemplary way through the spiritual ascent and death of St. Francis. In drawing out this association, Bonaventure develops a theory of the soul and its capacity for transformation in union with God that gives specificity to the Christian desire for self-abandonment in God and the annihilation of the soul in union with God. Though Bonaventure does not use the language of the soul coming to nothing, he describes a state of ecstasy or excessus mentis that is possible in this life, but which constitutes the death and transformation of the soul in union with God. -

Aquinas's Doctrine of Moral Virtue and Its Significance for Theories of Facility

AQUINAS'S DOCTRINE OF MORAL VIRTUE AND ITS SIGNIFICANCE FOR THEORIES OF FACILITY RENEE MIRKES, O.S.F. Director, Center for NaProEthics Omaha, Nebraska HOMISTIC COMMENTATORS from the post T Scholastic. era to the modern period generally restricted their discussions of Aquinas's doctrine on the relation ship between the acquired and infused virtues to the question of facility, that is, whether or not each kind of virtue facilitates the acts of the other. R. F. Coerver1 gives 1943 as a cutoff date for contemporary discussion of the question of facility in the infused . virtues. His 1946 dissertation on the topic notes that many theolo gians of his day had discarded the distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic facility and, with the exception of the manuals of Merkelbach (1871-1942) and Herve (1881-1958), "few of the modern theologians devote much space to the interrelation of the acquired and infused moral virtues." 2 'See Rev. Robert Florent Coerver, C.M., The Quality of Facility in the Moral Virtues, The Catholic University of America Studies in Sacred Theology 92 (Washington, D.C.: The Cathqlic University of America, 1946). ' Ibid., 113. A literature search from 1946 to 1994 (The Guide to Catholic Literature, Catholic Periodical and Literature Index, and American Theolo.gical Library Association Index) confirms Coerver's observation. The subject of facility in the moral virtues has not appeared as a topic of theological' investigation since the 1940s. An exception is Romanus Cessario's Moral Virtues and Theological Ethics ([Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1991], introduction, 10), which contains a section on the relationship of the acquired and infused moral virtues. -

The Cardinal and Theological Virtues

LESSON 5 The Cardinal and Theological Virtues BACKGROUND READING We don’t often reflect on the staying power Human or Cardinal Virtues that habits have in our lives. Ancient wisdom The four cardinal virtues are human virtues that tells us that habits become nature. We are what govern our moral choices. They are acquired repeatedly do. If we do something over and over by human effort and perfected by grace. The again, eventually we will do that thing without four cardinal virtues are: prudence, justice, thinking. For example, if a person has chewed temperance, and fortitude. The word cardinal her nails all of her life, then chewing nails comes from a Latin word that means “hinge” becomes an unconscious habit that is difficult or “pivot.” All the other virtues are connected to break. Perhaps harder to cultivate are the to, or hinge upon, the cardinal virtues. Without good habits in our lives. If we regularly take time the cardinal virtues, we are not able to live the to exercise, to say no to extra desserts, to get other virtues. up early to pray, to think affirming thoughts of Prudence “disposes practical reason to others, these too can become habits. discern our true good in every circumstance The Catechism of the Catholic Church and to choose the right means of achieving it” defines virtue as “an habitual and firm (CCC 1806). We must recall that our true good disposition to do the good. It allows the person is always that which will lead us to Heaven, so not only to perform good acts, but also to that perhaps another way of saying this is that give the best of himself. -

Can Augustine Offer Any Insight on Vocation? Megan Devore

“The Labors of our Occupation”: Can Augustine Offer Any Insight on Vocation? Megan DeVore Megan DeVore is Associate Professor of Church History and Early Christian Studies in the Department of Theology, School of Undergraduate Studies at Colorado Christian University, Lakewood, Colorado. She earned her PhD specializing in Early Christianity from the University of Wales Trinity Saint David in the United Kingdom. Dr. DeVore is a member of the North American Patristic Society, the American Society of Church History, the Society of Biblical Literature, the Evangelical Theological Society, and the American Classical League. Around the year 401, a curious incident transpired near Roman Carthage. A cluster of nomadic long-haired monks had recently wandered into the area, causing a stir among locals. These monks took the gospel quite seriously; that is, they lived very literally one part of a gospel, “Consider the birds of the air, for they neither sow, nor reap, nor gather into barns … Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow: they labor not” (Matt 6:26-29). They were apparently not only shunning all physical labor on behalf of medita- tive prayer, but they were also (at least according to Augustine’s depiction of the situation) imposing such unemployment upon others, namely local barbers. In response, Augustine penned a unique pamphlet. It takes the form of a retort, but as it unfolds, a commentary on the dignity and duty of work emerges—manual labor, in itself significant, as well as “the labors of our occupation” (labores occupationem nostrarum) and “labor according to our rank and duty” (pro nostro gradu et officio laborantibus, De Op. -

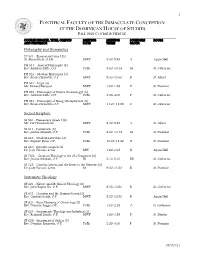

Fall 2021 Course Schedule ______Course Number, Title, Credits Meeting Meeting Schedule Room and Professor Days Times Block

1 PONTIFICAL FACULTY OF THE IMMACULATE CONCEPTION AT THE DOMINICAN HOUSE OF STUDIES FALL 2021 COURSE SCHEDULE _____________________________________________________________________________________________ COURSE NUMBER, TITLE, CREDITS MEETING MEETING SCHEDULE ROOM AND PROFESSOR DAYS TIMES BLOCK Philosophy and Humanities LT 501 - Elementary Latin I [3] Sr. Maria Kiely, O.S.B. MWF 8:50-9:45 A Aquin Hall PH 511 - Ancient Philosophy [3] Rev. Ambrose Little, O.P. TuTh 8:50-10:15 M St. Catherine PH 513 - Modern Philosophy [3] Rev. Brian Chrzastek, O.P. MWF 9:55-10:50 B St. Albert PH 521 - Logic [3] Mr. Richard Berquist MWF 1:00-1:55 D St. Dominic PH 523 - Philosophy of Nature (Cosmology) [3] Rev. Ambrose Little, O.P. TuTh 2:35-4:00 P St. Catherine PH 551 - Philosophy of Being (Metaphysics) [3] Rev. Brian Chrzastek, O.P. MWF 11:00-11:55 C St. Catherine Sacred Scripture SS 581 - Elementary Greek I [3] Mr. Carl Vennerstrom MWF 8:50-9:45 A St. Albert SS 611 - Pentateuch [3] Rev. Jordan Schmidt, O.P. TuTh 8:50-10:15 M St. Dominic SS 632 - Wisdom Literature [3] Rev. Stephen Ryan, O.P. TuTh 10:25-11:50 N St. Dominic SS 640 - Synoptic Gospels [3] Dr. Jody Vaccaro Lewis MW 1:00-2:25 H Aquin Hall SS 700L – Creation Theology in the Old Testament [3] Rev. Jordan Schmidt, O.P. W 3:10-5:10 BB St. Catherine SS 765 – Catholic Letters and the Letter to the Hebrews [3] Dr. Jody Vaccaro Lewis M 9:50-11:50 R St. -

From the Catechism of the Catholic Church, Second Edition Person, Nature, & Human Flourishing Aquinas College, Nashville, Tennessee March 9, 2020

From The Catechism of the Catholic Church, Second Edition Person, Nature, & Human Flourishing Aquinas College, Nashville, Tennessee March 9, 2020 NOTE: To check the footnotes, please refer to a printed copy of the Catechism or an on-line version. THE VIRTUES 1803 "Whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is gracious, if there is any excellence, if there is anything worthy of praise, think about these things."62 A virtue is an habitual and firm disposition to do the good. It allows the person not only to perform good acts, but to give the best of himself. The virtuous person tends toward the good with all his sensory and spiritual powers; he pursues the good and chooses it in concrete actions. The goal of a virtuous life is to become like God.63 I. THE HUMAN VIRTUES 1804 Human virtues are firm attitudes, stable dispositions, habitual perfections of intellect and will that govern our actions, order our passions, and guide our conduct according to reason and faith. They make possible ease, self-mastery, and joy in leading a morally good life. The virtuous man is he who freely practices the good. The moral virtues are acquired by human effort. They are the fruit and seed of morally good acts; they dispose all the powers of the human being for communion with divine love. The cardinal virtues 1805 Four virtues play a pivotal role and accordingly are called "cardinal"; all the others are grouped around them. They are: prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance. -

The Cardinal and Theological Virtues • Goal of the Virtuous Life Is To

9/2/2019 RCIA 9: The Cardinal and Theological Virtues 9: The Cardinal and Theological Virtues Virtuous Living • Goal of the virtuous life is to become like God • Living in truth and love is the only authentic response to… You, therefore, must be perfect, as your Heavenly Father is perfect (Matthew 5:48) 2 9: The Cardinal and Theological Virtues Virtuous Living Grace and Virtue • Virtue: “habitual and firm disposition to do the good” (CCC 103) • Good is known thru grace & faith working in love 3 1 9/2/2019 9: The Cardinal and Theological Virtues Virtuous Living The Human Virtues • Firm attitudes • Stable dispositions • Habitual perfections of intellect & will • Govern actions • Order passions • Guide conduct • Acquired by human effort • Elevated by sacramental graces 4 9: The Cardinal and Theological Virtues Virtuous Living The Cardinal Virtues • Prudence – Directs what is to be done or avoided in the pursuit of good 5 9: The Cardinal and Theological Virtues Virtuous Living The Cardinal Virtues (cont.) • Justice – Helps promote equality between persons – The foundation for any society 6 2 9/2/2019 9: The Cardinal and Theological Virtues Virtuous Living The Cardinal Virtues (cont.) • Fortitude – Strength to accomplish good actions in the face of difficulties 7 The Fortitude (1470) by Sandro Botticelli 9: The Cardinal and Theological Virtues Virtuous Living The Cardinal Virtues (cont.) • Temperance – Moderation – balance desires to achieve true happiness Representation of temperance (painted wood sculpture, dated 1683, which covers the shrine -

Virtues, Perfectionism and Natural Law

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF LEGAL STUDIES – VOL 3 ISSUE 1 (2010) Virtues, Perfectionism and Natural Law Michele Mangini * I. Premise Many contend that liberalism is weak from the point of view of value orientation, because it neglects that central part of human experience which is expressed by substantive ideas of the good, such as human flourishing, the good life, human goodness, and the like. This paper argues that there is a long tradition, in the Western culture, of a substantive view of human goodness revolving around the notion of ‘virtues’. This tradition is supportive of, and still belongs to, liberal political theory insofar as one accepts the assumption that the cultural (and especially the ethical) presuppositions of liberalism are (at least, partly) embodied in natural law . The work of ‘retrieval’ and analysis necessary to forward this argument will be founded on a few claims concerning the compatibility between the ethical core of the virtues and liberalism. The substantive proposal of human goodness that is put forward, named ‘agency goods perfectionism’, is an attempt at establishing some continuity between a morality based on the virtues, in agreement with the natural law tradition, and a political morality in which liberal pluralism is balanced by some degree of value orientation through ‘general and vague’ conceptions of the virtues. The argument is aimed at showing more overlap than what is usually accepted between, on one hand, a secular political theory such as liberalism and, on the other hand, a religiously inspired conception such as natural law. In order to defend this thesis, this paper challenges some competing substantive ethical theories, such as objective list theories and new natural law theory; which are also aimed at addressing the problem of value-orientation, but from a perspective that is threatening the fundamental liberal presupposition of freedom of choice. -

Growing in Virtue

BHCDSB_Growing_Virtue:Layout 1 6/29/11 12:17 PM Page 1 Growing in Virtue Brant Haldimand norfolk CatHoliC distriCt sCHool Board 322 Fairview Drive, P.O. Box 217 Brantford, ON N3T 5M8 t 519.756.6369 E [email protected] www.bhncdsb.ca Excellence in Learning ~ Living in Christ Acknowledgements A special thanks to the following who devoted their passion and energy to creating and supporting this work. Writers Kathleen Evans, Principal, Holy Trinity Catholic High School, Simcoe Laurence McKenna, Religion Teacher, St. John’s College, Brantford Linda Mooney, Chaplaincy Leader, Holy Trinity Catholic High School, Simcoe Marian O’Connor, Secondary Program Consultant, BHNCDSB Reviewers Sharon Boase, Chaplaincy Leader, St. John’s College, Brantford Carolyn Boerboom, Teacher, St. Gabriel School, Brantford Mary Gallo, Principal of Program, Secondary, BHNCDSB Sean Roche, Religion Teacher, Assumption College School, Brantford Joyce Young, Religion and Family Life Consultant, BHNCDSB Trish Kings, Superintendent of Education, BHNCDSB Fall, 2011 Forward The Brant Haldimand Norfolk Catholic District School Board's Mission Statement provides us with direction for the work in our Catholic Schools. On a daily basis, "we provide faith formation and academic excellence." Our Catholic faith is infused in all we do. The Ontario Ministry of Education has introduced its Character Development Initiative. This has provided Catholic School Boards with the unique opportunity to highlight and celebrate what has always been a central component and tradition to Catholic schools: Catholic virtues. I am very pleased to present our Board's new foundational document on Virtues Education, which will act as an excellent resource for teachers, principals and curriculum writers. -

Faith Hope and Love in the Theological Tradition

Faith, Hope, and Love as Virtues in the Theological Tradition Green Paper (October 2016) Lead Author: David Batho The University of Essex Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 2 2: Saint Paul ...................................................................................................................... 2 3: Saint Augustine ............................................................................................................. 6 4: Saint Thomas Aquinas ................................................................................................. 17 a) Aquinas’s Predecessors ......................................................................................................... 17 b) Aquinas ................................................................................................................................. 21 5: Reformation Theology ................................................................................................. 32 6: Paul Tillich ................................................................................................................... 48 7: Conclusion ................................................................................................................... 60 Bibliography .................................................................................................................... 64 1 1. Introduction In this Green Paper we shall provide an overview of the history