Health Status and Health Behaviours in Neighbourhoods a Comparison Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North West Sector Profile

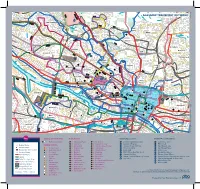

Appendix North West Sector Profile Contents 1. Introduction Page 1 2. Executive Summary Page 2 3. Demographic & Socio – Economic Page 8 4. Labour Market/Employment/Education Page 13 5. Health Page 23 6. Neighbourhood Management Page 29 1. Introduction 1.1 The profile provides comparative information on the North West Sector Community Planning Partnership (CPP) area, including demographic & socio economic, employment, health and neighbourhood management information. 1.2 North West Glasgow is diverse in socio economic terms, as illustrated by the map, as it contains Glasgow’s city centre/ business area, the more affluent west end of Glasgow but also localities with significant issues relating to employment, health and poverty. The North West is the academic centre of the City with the three Glasgow Universities located in the sector and also has many cultural & historical buildings of interest as well as large areas of green space. Table 1: North West Sector Summary Population (2011 Census) 206,483 (up 7.1%) Population (2011 Census) exc. communal establishments 197,419 Working Age Population 16-64 (2011 Census) 151,345 (73.3%) Electorate (2014) 165,009 Occupied Households (2011 Census) 101,884 (up 9.5%) Average Household Size (2011) exc. communal establishments 1.94 (2.07 in 2011) Housing Stock (2014) 105,638 No. of Dwellings per Hectare (2012) 22.28 Out Of Work Benefit Claimants (May 2014) 24,230 (16.0%) Job Seekers Allowance (February 2015) 5,141 (3.4%) 2. Executive Summary Demographic Information 2.1 Population According to the 2011 Census, The North West sector population was 206,483. The population in the North West Sector increased by 13,773 (7.1%) from 2001 Census. -

Campus Travel Guide Final 08092016 PRINT READY

Lochfauld V Farm ersion 1.1 27 Forth and 44 Switchback Road Maryhill F C Road 6 Clyde Canal Road Balmore 1 0 GLASGOW TRANSPORT NETWORK 5 , 6 F 61 Acre0 A d Old Blairdardie oa R Drumchapel Summerston ch lo 20 til 23 High Knightswood B irkin e K F 6 a /6A r s de F 15 n R F 8 o Netherton a High d 39 43 Dawsholm 31 Possil Forth and Clyde Canal Milton Cadder Temple Gilshochill a 38 Maryhill 4 / 4 n F e d a s d /4 r a 4 a o F e River Lambhill R B d Kelvin F a Anniesland o 18 F 9 0 R 6 n /6A 1 40 r 6 u F M 30 a b g Springburn ry n h 20 i ill r R Ruchill p Kelvindale S Scotstounhill o a Balornock 41 d Possil G Jordanhill re Park C at 19 15 W es 14 te rn R 17 37 oa Old Balornock 2 d Forth and D um Kelvinside 16 Clyde b North art 11 Canal on Kelvin t Ro Firhill ad 36 ee 5 tr 1 42 Scotstoun Hamiltonhill S Cowlairs Hyndland 0 F F n e 9 Broomhill 6 F ac 0 r Maryhill Road V , a ic 6 S Pa tor Dowanhill d r ia a k D 0 F o S riv A 8 21 Petershill o e R uth 8 F 6 n F /6 G r A a u C 15 rs b R g c o u n Whiteinch a i b r 7 d e Partickhill F 4 p /4 S F a River Kelvin F 9 7 Hillhead 9 0 7 River 18 Craighall Road Port Sighthill Clyde Partick Woodside Forth and F 15 Dundas Clyde 7 Germiston 7 Woodlands Renfrew Road 10 Dob Canal F bie' 1 14 s Loa 16 n 5 River Kelvin 17 1 5 F H il 7 Pointhouse Road li 18 5 R n 1 o g 25A a t o Shieldhall F 77 Garnethill d M 15 n 1 14 M 21, 23 10 M 17 9 6 F 90 15 13 Alexandra Parade 12 0 26 Townhead 9 8 Linthouse 6 3 F Govan 33 16 29 Blyt3hswood New Town F 34, 34a Anderston © The University of Glasgo North Stobcross Street Cardonald -

Download (18MB)

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] FOREIŒ DIVESTMENT AND EMPLOYEE DISCLOSURE AND CONSULTATION IN THE UK, 1978-1985. by Michael C. McDermott Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. School of Financial Studies, University of Glasgow, August 1986. ProQuest Number: 10991898 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10991898 Published by ProQuest LLO (2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLO. -

March 2014 Jordanhill School Journal

Jordanhill School Journal March 2014 Rector Contents One of the challenges for the Journal 3 Two Special Birthdays is to speak across the generations of Jordanhill pupils and parents. Like the 4 Youth Philanthropy Initiative school magazines of generations past 5 Charity Dinner the Journal captures some of our annual activities and news. Today much of our 6 Our Houses current affairs is broadcast through 8 JCS and Scouts other channels such as the regular 11 Reflections on Upenn newsletters, our electronic bulletins and on the web site. All of our readers like to read about and 14 Teacher Exchange Australia to see both those activities which are constant features of the Scotland school and the many new excitements and opportunities 16 Teacher Exchange Scotland to which come along. Australia 18 CERN At the same time, our older contributors provide thought- provoking articles which in turn continue to stimulate our 21 Wind Band wider readership to write in. Thank you to everyone who 22 Mike Russell has contributed to this edition. 23 Queens Baton Relay Some things like the four Houses have always been with 24 Commonwealth Games us have they not? Yet the extract from the 1939 magazine reminds us that at one time that too was a new feature 26 Berlin of the school. 28 Community Tea Party 29 Art Competition Winners We have now been advised that the David Stow building will finally close to all users this summer as the 32 Art University of Strathclyde moves to market the campus for Current and back copies of the Journal redevelopment. -

33 Garscadden Road Old Drumchapel Glasgow G15 6UW Clydeproperty

33 Garscadden Road Old Drumchapel Glasgow G15 6UW To view the HD video click here clydeproperty.co.uk | page 1 clydeproperty.co.uk A significantly extended, three/four bedroom, semi-detached villa occupying an enviable corner position. Originally, the home formed part of the clubhouse of Old Drumchapel Golf Club (opened in 1905) and has been sympathetically and creatively transformed into an impressive family home retaining a host of impressive, period features. Garscadden Road consists of a varied assortment of fine period homes and offers a convenient location, a short drive from Bearsden and its southern end, adjoins the A82/Great At a glance Western Road leading west in the direction of Loch Lomond and the Significantly extended Erskine Bridge towards Glasgow Airport and east, to Glasgow City Centre and Anniesland Cross. The area is served by a number of Sizeable corner plot supermarkets, schooling at all levels, a number of golf clubs, sports Stunning features including astragal windows, open centres, shops and restaurants. fires, original doors and bell push, ornate handles and picture rails Stunning, refitted kitchen (installed 2016) Versatile accommodation of seven principal apartments Level gardens The finer detail Partially double-glazed and beautiful, single-glazed astragal windows retained with secondary glazing Gas central heating with Vokera combination boiler Driveway, car port and garage Convenient for transport and schooling EPC Band E Connect & Share. View the video in HD, simply download our APP, hover over the cover and see it come to life. clydeproperty.co.uk | page 3 clydeproperty.co.uk | page 4 This beautifully presented, traditional home is immediately impressive on arrival and the extended accommodation is also far larger than the facade belies. -

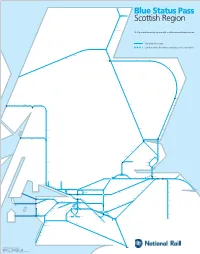

Blue Status Pass Junction Wick

Thurso Georgemas Blue Status Pass Junction Wick Scotscalder Altnabreac Forsinard Scottish Region Kinbrace Kildonan Helmsdale Brora Dunrobin Castle summer only Golspie The Blue Status Pass for this region is valid on all lines and at all stations shown. Rogart Lairg Invershin Culrain Ardgay Tain Fearn National Rail routes Invergordon Alness Limited service (limitation varies by service / operator) Achanalt Lochluichart Garve Dingwall Achnasheen Muir of Ord Achnashellach Beauly Strathcarron Nairn Forres Elgin Inverness Attadale Keith Stromeferry Huntly Duncraig Plockton Carrbridge Insch Duirinish Kyle of Lochalsh Inverurie Aviemore Kingussie Dyce Newtonmore Aberdeen Portlethen Loch Eil Dalwhinnie Morar Beasdale Glenfinnan Outward Bound Banavie Spean Bridge Roy Bridge Stonehaven Mallaig Arisaig Lochailort Locheilside Corpach Fort William Laurencekirk Tulloch Montrose Blair Atholl Arbroath Corrour Carnoustie Pitlochry Golf Street Rannoch Barry Links Dunkeld & Birnam Monifieth Bridge of Orchy Balmossie Broughty Ferry Taynuilt Loch Awe Tyndrum Lower Upper Tyndrum Oban Connel Ferry Falls of Cruachan Dalmally summer only Invergowrie Dundee Crianlarich Perth Gleneagles Leuchars Ardlui Dunblane Cupar Springfield Ladybank Bridge of Allan Glenrothes with Thornton Markinch Cardenden Lochgelly Cowdenbeath Arrochar & Tarbet Stirling Alloa Dunfermline Queen Margaret Kirkcaldy Kinghorn Dunfermline Town Burntisland Aberdour Rosyth Dalgety Bay Larbert Inverkeithing North Queensferry Garelochhead Dalmeny Camelon North Berwick Edinburgh Gateway Falkirk Grahamston -

Priest: Fr Gerry Fitzpatrick 0141-427-0293 [email protected] Web: Masses Sunday Vigil at 6.00 on Saturday

priest: Fr Gerry Fitzpatrick 0141-427-0293 [email protected] web: www.stleothegreat.org.uk Masses Sunday Vigil at 6.00 on Saturday. Morning Masses 9.30 and 11.00 Tea and toast in the Hall after 9.30 and 11.00 Sunday Masses. Weekdays Morning Prayer at 10.00. Mass10.05 In the name of God the Father, In the name of God the Son, In the name of God the Holy Spirit, in the name of God. In the name of God the Father, In the name of God the Son, In the name of God the Holy Spirit, in the name of God. We praise you, we bless you, we adore you, we glorify you, we give you thanks for your great glory, Lord God, heavenly King, O God, almighty Father. Lord Jesus Christ, Only Begotten Son, Lord God, Lamb of God, Son of the Father, you take away the sins of the world, have mercy on us; you take away the sins of the world, receive our prayer; you are seated at the right hand of the Father, have mercy on us. For you alone are the Holy One, you alone are the Lord, you alone are the Most High, Jesus Christ, with the Holy Spirit, in the glory of God the Father. Printed by BoltPDF (c) NCH Software. Free for non-commercial use only. A Reading from the Prophet Isaiah 42: 1-4, 6-7 Psalm 15: You show your friends the path of life, give them the fullness of joy. I say to the Lord : you are my God. -

Financial Inclusion Pathways Event Presentation

What is the child poverty challenge in Scotland? Hanna McCulloch, Policy & Parliamentary Officer, Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG) in Scotland Addressing child poverty in Scotland 1 in 5 (220,000) children live in poverty in Scotland So what is the ‘child poverty line’ using a relative measure? Lone parent with 2 kids £291 per week a week 2 parent family (2 kids) £393 a week SLIDE TITLE / DATE DD/MM/YY / SLIDE NUMBER Rates of child poverty in Scotland Overall: 1 in 5 Disabled households:1 in 3 Lone parents: 2 in 3 Child poverty Glasgow City 34.05% rates Linn 32 % Newlands/Auldburn 31 % (AHC) Greater Pollok 33 % Craigton 31 % Govan 38 % Pollokshields 33 % Langside 25 % Southside Central 40 % Calton 43 % Anderston/City 32 % Hillhead 28 % Partick West 25 % Garscadden/Scotstounhill 35 % Drumchapel/Anniesland 36 % Maryhill/Kelvin 31 % Canal 39 % Springburn 42 % Royal College of paediatrics and child health Poverty is the “biggest cause of poor health” in society and “children living in the most deprived areas are much more likely to be in poor health, be overweight or obese, suffer from asthma, have poorly managed diabetes, experience mental health problems, and die early.” Projected child poverty (%) BHC SUB TITLE 25.7 24.7 Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipisicing23.3 elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore21.8 et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in 19.7 reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. -

Greater Glasgow

OFFICIAL Greater Glasgow Contact Organisation Address E-mail Number 07710 Ahl Al Bait Society 25 Woodside Place, Glasgow, G3 7QL [email protected] 514637 Citywall House, 32 Eastwood Avenue, Glasgow, 0141 212 Amina [email protected] G41 3NS 8420 0141 634 Ardenglen Housing Association 355 Tormusk Rd, Castlemilk, Glasgow G45 0HF [email protected] 8016 0141 553 Blochairn Housing Association 1 Blochairn Road, Glasgow, G21 2ED [email protected] 0022 G6 Flemington House, 110 Flemington St, 0141 558 Bridges Programme Suite [email protected] Springburn, G21 4BF 9749 1st Floor Central Chambers Suite 58 93 Hope St 0141 248 British Deaf Association (Scotland) [email protected] Glasgow G2 6LD 5565 3rd Floor, Cambridge House, 8 Cambridge Street, 0141 331 British Red Cross [email protected] Glasgow, G2 3DZ 4170 OFFICIAL OFFICIAL 0141 945 Cadder Housing Association 66 Skirsa Street, Glasgow, G23 5BA [email protected] 3282 Suite 5-7, McGregor House, 10 Donaldson 0141 775 Ceartas Advocacy [email protected] Crescent, Kirkintilloch, G66 1XF 0433 0141 552 43 Tharsis Street, Glasgow, G21 2JF [email protected] Copperworks Housing 7477 0141 774 Cranhill Development Trust 109 Bellrock Street, Glasgow, G33 3HE [email protected] 3344 0141 777 Deaf Blind Scotland 1 Neasham Drive, Kirkintilloch, G66 3FA [email protected] 6111 0141 584 DRC Generations 102 Kingsway, Glasgow, G14 9YS [email protected] 5754 07482 East Renfrewshire Disability Action 56 Kelburn Street, Barrhead, G78 -

2Nd Glasgow Scout Group

2ND GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 71 GLENCAIRN DRIVE GLASGOW G414PN 100% 30TH GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 37 LAMMERMOOR AVENUE GLASGOW G523BE 100% 360 DEGREES FINANCE LTD 40 WASHINGTON STREET GLASGOW G38AZ 100% 360CRM LTD 80 ST VINCENT STREET GLASGOW 25% 3RD GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 121 SHAWMOSS ROAD GLASGOW G414AE 100% 43RD GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 4 HOLMHEAD ROAD GLASGOW G443AS 100% 4C DESIGN LIMITED 100 BORRON STREET GLASGOW 25% 4C DESIGN LTD 100 BORRON STREET GLASGOW 25% 50TH GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 23 GARRY STREET GLASGOW G444AZ 100% 55 NORTH LTD 19 WATERLOO STREET GLASGOW G26AY 100% 55 NORTH LTD 19 WATERLOO STREET GLASGOW G26AY 100% 7 SEATER CENTRE (SCOTLAND) LTD 1152 TOLLCROSS ROAD GLASGOW G328HE 100% 72ND GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 500 A CROW ROAD GLASGOW G117DW 100% 86TH/191 GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 79 SANDA STREET GLASGOW G208PT 100% 965 LTD 965 DUKE STREET GLASGOW 100% 9TH GLASGOW SCOUT GROUP 99 THORNWOOD PLACE GLASGOW 100% A & E BROWN (PLUMBERS MERCHANTS) LTD 1320 SPRINGBURN ROAD GLASGOW G211UT 25% A & F MCKINNON LTD 391 VICTORIA ROAD GLASGOW G428RZ 100% A & G INVESTMENTS LLP 12 RENFIELD STREET GLASGOW 100% A & G INVESTMENTS LLP 12 RENFIELD STREET GLASGOW 100% A& L LTD 12 PLEAN STREET GLASGOW G140YH 25% A & M TRAINING LTD 28 ADAMSWELL STREET GLASGOW 100% A & P MACINTYRE LTD 213 CLARKSTON ROAD GLASGOW G443DS 25% A A MENZIES & CO 180 QUEEN MARGARET DRIVE GLASGOW G208NX 100% A A MOTORS LTD 7 MORDAUNT STREET GLASGOW 50% A ALEXANDER & SON (ELECTRICAL) LTD 9 CATHKINVIEW ROAD GLASGOW G429EH 25% A ALEXANDER & SON(ELECTRICAL) LTD 24 LOCHLEVEN ROAD GLASGOW G429JU 100% A B FRAMING -

Board Paper 05/57

NOT YET ENDORSED AS A CORRECT RECORD Paper No: 05/57 Pharmacy Practices Committee (03) Minutes of a Meeting held on Tuesday 7th June 2005 Seminar Room, Homoeopathic Hospital, Great Western Road, Glasgow, G12 PRESENT: Andrew Robertson Chairman Alan Fraser Lay Member William Reid Deputy Lay Member Prof W J McKie Deputy Lay Member Dr James Johnson Non Contractor Pharmacist Member Gordon Dykes Contractor Pharmacist Member Alasdair Macintyre Contractor Pharmacist Member IN ATTENDANCE Margaret Cluer Family Health Services Janine Glen Contractor Services Manager Prior to the consideration of business, the Chairperson asked members ACTION if they had an interest in any of the applications to be discussed or if they were associated with a person who had a personal interest in the applications to be considered by the Committee. No declarations of interest were made. 1. APOLOGIES Apologies were received on behalf of Patricia Cox and David Thomson. 2. MINUTES The Minutes of the meeting held on Tuesday 5th April 2005 PPC[M]2005/02 were approved as a correct record. 3. ANY OTHER BUSINESS NOT INCLUDED IN AGENDA Janine advised the Committee that three appeals had been received objecting to the decision taken at the last meeting to grant Colin and Ann Fergusson’s application to provide services at 194 (not confirmed) Petershill Road, Glasgow G21. Two of the appeals had been forwarded to the National Appeals Panel for their determination. The third appeal had been received outwith the statutory timescale contained in the Regulations, and as such the appellant had been informed that no action could be taken. -

Business Land Review

Local Development Plan 2 October Monitoring Statement 2019 Appendix 1 - Business Land Review Business Land Review, April 2019 East Dunbartonshire Council Contents Section Page 1 INTRODUCTION 4 2 POLICY AND EVIDENCE REVIEW 5 3 BASELINE ECONOMIC ANALYSIS 10 4 PROPERTY MARKET REVIEW 23 5 BUSINESS SURVEY 30 6 AUDIT OF EMPLOYMENT SITES 33 7 DEMAND ASSESSMENT 108 8 SUPPLY AND DEMAND BALANCE 120 9 CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 123 GL Hearn Page 2 of 125 J: \Planning\Job Files\East Duns\EDC BLR Report.docx Business Land Review, April 2019 East Dunbartonshire Council Quality Standards Control The signatories below verify that this document has been prepared in accordance with our quality control requirements. These procedures do not affect the content and views expressed by the originator. This document must only be treated as a draft unless it is has been signed by the Originators and approved by a Business or Associate Director. DATE ORIGINATORS APPROVED April 2019 Nena Pavlidou, Senior Planner Paul McColgan Director Limitations This document has been prepared for the stated objective and should not be used for any other purpose without the prior written authority of GL Hearn; we accept no responsibility or liability for the consequences of this document being used for a purpose other than for which it was commissioned. GL Hearn Page 3 of 125 J: \Planning\Job Files\East Duns\EDC BLR Report.docx Business Land Review, April 2019 East Dunbartonshire Council 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 GL Hearn was commissioned by East Dunbartonshire Council to undertake a comprehensive review of the business, industrial and employment land and premises within its administrative boundaries.