Remembering Earth Day: the Struggle Over Public Memory in Virtual Spaces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chris Hoeser Center Calendar 4:00—Friday Fun—LR All Fools’ Day Good Friday 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 :30—Bus to St

Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 9:30—Dancercise—LR 9:30—Friday Dance Party—LR 9:30—Saturday Sing A 10:00—Sacrament of 11:00—Good Friday Long—LR Reconciliation—C Traditions—LR 11:15—News Crew—LR 11:00—All About April Fools’ 1:30—Visit from the Easter 3:30—Ice Cream Sundae Bunny w/ Goodies—Rooms Day—LR Social—LR 2:30—Bus to St. Andrew’s 2:15—BINGO—Dining Room Catholic Church for Stations 4:00—Punny April—LR Happy Birthday, Ice Cream of the Cross—NS Sundae Chris Hoeser Center Calendar 4:00—Friday Fun—LR All Fools’ Day Good Friday 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 :30—Bus to St. Andrew’s 9:30—Monday Morning Music— 9:30—Bible Study with Pastor 9:30—Balloon Volleyball—LR 9:30—Dancercise—LR 9:30—Friday Dance Party— 9:30—Saturday Sing A Catholic Church—NS LR Al—LR 11:00—Suncatcher Craft—LR 10:00—Joy Ride—NS LR Long—LR 11:00—What Makes You 1:00—All About Easter—LR 11:00—Tuesday Taboo—LR 2:30—Nail Polishing—Rooms 11:00—Hand Massages—LR 11:00—EZ Music: The Sound 11:15—Extra! Extra! Read All 3:30—Spiritual Sunday—LR Happy?—LR 2:15—BINGO—Dining Room 4:00—Short Story: For the 2:15—BINGO—Dining Room of Music or The Wizard of About It!—LR 2:30—Bean Bag Toss 4:00—Remembering Going to Birds—LR 4:00—Can You Picture Oz—LR 3:30—Discuss & Recall—LR Challenge—LR the Zoo—LR This?—LR 2:15—All About Kites: It’s Kite 4:00—Junk Drawer Detectives— Month!—LR LR Giggles & Guffaws Day 4:00—Musical Miming—LR Be Happy Day Easter Sunday 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 9:30—Bus to St. -

Recycling Newsletter

LONDONDERRY RECYCLING NEWS SPRING& SUMMER 2021 I S S U E # 7 8 I N S I D E THIS ISSUE: DROP OFF CENTER—2021 Season *Note: New Hours* Saturday Hours: Waste Day Apr. 17, thru Nov. 20, 2021 *7:30 AM - 3:30 PM* Earth Day 2 Summer Wednesday Hours: Beautify 2 Apr. 21, - Sept. 9, 2021, 3:00 - 7:00 PM Londonderry To maintain proper social distancing and to ensure employee and resident’s safety, EPA 2 the Drop Off Center attendants will allow only a limited number of vehicles into the Stormwater gated area at one time. Residents may experience delays. Residents should follow Household 3 CDC Face Mask guidelines while at the Drop Off Center. As a reminder, payment is Hazardous by check only and residents should make every effort to bring their own pens. We ask for your patience while we provide this service during these unusual times. Overflow Bag 3 What to 4 Disposal fees are due at the time of service, BY CHECK Only—No Cash is accepted Recycle Items Disposal Fee* Items Disposal Fee* No Plastic Bags 4 Scrap Metal: $5 per load (any size) - Pool Chemical 4 Aluminum, steel, brass, copper Propane 20 lb. tanks $4, Disposal •No Freon appliances Tanks small 1 lb. tanks free Trash & 4 •No refrigerators, No freezers Furniture: Small Items $7 each (chair, twin Recycling Holi- •No air conditioners mattress) day Schedule Construction Minimum $7 up to 55 gal. barrel Large Items $14 each (sofa, full Waste Oil 4 Debris: $24 per cubic yard mattress, table etc.) Collection $36 6 ft. -

Confessions of a Greenpeace Dropout: the Making of a Sensible Environmentalist

An Excerpt from Confessions of a Greenpeace Dropout: The Making of a Sensible Environmentalist ou could call me a Greenpeace dropout, but that is not an entirely accurate Ydescription of how or why I left the organization 15 years after I helped create it. I’d like to think Greenpeace left me, rather than the other way around, by but that too is not entirely correct. Patrick The truth is Greenpeace and I underwent divergent evolutions. I became Moore a sensible environmentalist; Greenpeace became increasingly senseless as it adopted an agenda that is antiscience, antibusiness, and downright antihuman. This is the story of our transformations. The last half of the 20th century was marked by a revulsion for war and a new awareness of the environment. Beatniks, hippies, eco-freaks, and greens in their turn fashioned a new philosophy that embraced peace and ecology as the overarching principles of a civilized world. Spurred by more than 30 years of ever-present fear that global nuclear holocaust would wipe out humanity and much of the living world, we led a new war—a war to save the earth. I’ve had the good fortune to be a general in that war. My boot camp had no screaming sergeant or rifle drills. Still, the sense of duty and purpose of mission we had at the beginning was as acute as any assault on a common enemy. We campaigned against the bomb-makers, whale-killers, polluters, and anyone else who threatened civilization or the environment. In the process we won the hearts and minds of people around the world. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23

1 LEXINGTON LAW GROUP Howard Hirsch, State Bar No. 213209 2 Ryan Berghoff, State Bar No. 308812 Meredyth Merrow, State Bar No. 328337 3 503 Divisadero Street San Francisco, CA 94117 4 Telephone: (415) 913-7800 Facsimile: (415) 759-4112 5 [email protected] [email protected] 6 [email protected] 7 LAW OFFICE OF GIDEON KRACOV Gideon Kracov, State Bar No. 179815 8 801 S. Grand Ave., 11th Floor Los Angeles, CA 90017 9 Telephone: (213) 629-2071 Facsimile: (213) 623-7755 10 [email protected] 11 Attorneys for Plaintiff GREENPEACE, INC. 12 13 14 SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA 15 COUNTY OF ALAMEDA 16 17 GREENPEACE, INC., Case No. 18 Plaintiff, COMPLAINT 19 v. 20 WALMART, INC.; and DOES 1 through 100, 21 inclusive, 22 Defendants. 23 24 25 26 27 28 DOCUMENT PREPARED ON RECYCLED PAPER COMPLAINT 1 Plaintiff Greenpeace, Inc. (“Plaintiff” or“Greenpeace”), based on information, belief, and 2 investigation of its counsel, except for information based on knowledge, hereby alleges: 3 INTRODUCTION 4 1. The problems associated with plastic pollution are increasing on a local, national, 5 and global scale. This affects the amount of plastic in the ocean, in freshwater lakes and streams, 6 on land, and in landfills. Nearly 90% of plastic waste is not recycled, with billions of tons of 7 plastic becoming trash and litter.1 According to a new study, at least 1.2 to 2.5 million tons of 8 plastic trash from the United States was dopped on lands, rivers, lakes and oceans as litter, were 9 illegally dumped, or shipped abroad and then not properly disposed of.2 As consumers become 10 increasingly aware of the problems associated with plastic pollution, they are increasingly 11 susceptible to marketing claims reassuring them that the plastic used to make and package the 12 products that they purchase are recyclable. -

TCM 793 Book

Earth Day Earth Day was first held in the United States on April 22, 1970, and was founded by United States Senator Gaylord Nelson. The second Earth Day, held on April 22, 1990, was celebrated in over 140 countries. Earth Day is a day to remind us of the need to care for our environment. It is a time to become actively involved in many Save-the-Earth projects. Another related holiday held nationally in the United States on the last Friday of April is Arbor Day, a day to plant new trees and emphasize conservation. It was first held in Nebraska on April 10, 1872, and its founder was conservation advocate Julius Sterling Morton. The date for Arbor Day may vary depending on the state in which you live. Activities Start a school-wide recycling program. Collect aluminum cans, plastic bottles, paper, and glass. Put collection points around the school. If possible, have a curbside drop-off point one day a week so the public can support your efforts. Recruit some adults to help with transportation to a recycling center. This may be coordinated by your class or by your school’s student government. Decide on a worthwhile organization that helps the earth and contribute the money you earn to it. Create a bulletin board. Use the classified section of the newspaper as the background for this bulletin board. Title the board “The Daily Planet.” Throughout the unit, have students bring in and post articles from newspapers or magazines that tell about environmental problems that the world is facing. -

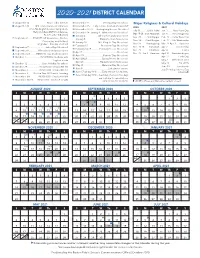

2020–2021District Calendar

2020–2021 DISTRICT CALENDAR August 10-14 ...........................New Leader Institute November 11 .................... Veterans Day: No school Major Religious & Cultural Holidays August 17-20 ........ BPS Learns Summer Conference November 25 ..... Early release for students and staff 2020 2021 (TSI, ALI, English Learner Symposium, November 26-27 ....Thanksgiving Recess: No school July 31 ..........Eid al-Adha Jan. 1 ........New Year’s Day Early Childhood/UPK Conference, December 24- January 1 ..Winter Recess: No school Sep. 19-20 ..Rosh Hashanah Jan. 6 ......Three Kings Day New Teacher Induction) January 4.................... All teachers and paras report . Sep. 28 .........Yom Kippur Feb. 12 .... Lunar New Year September 1 ......REMOTE: UP Academies: Boston, January 5...................... Students return from recess Nov. 14 ...... Diwali begins Feb. 17 ... Ash Wednesday Dorchester, and Holland, January 18..................M.L. King Jr. Day: No school all grades − first day of school Nov. 26 .......Thanksgiving Mar. 27-Apr. 3 ..... Passover February 15 .................... Presidents Day: No school September 7 .......................... Labor Day: No school Dec. 10-18 .......Hanukkah Apr. 2 ............ Good Friday February 16-19.............February Recess: No school September 8 .............. All teachers and paras report Dec. 25 ............Christmas Apr. 4 ...................... Easter April 2 ...................................................... No school September 21 ..........REMOTE: ALL Students report Dec. -

Greenpeace, Earth First! and the Earth Liberation Front: the Rp Ogression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America" (2008)

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Senior Honors Projects Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island 2008 Greenpeace, Earth First! and The aE rth Liberation Front: The rP ogression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America Christopher J. Covill University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Covill, Christopher J., "Greenpeace, Earth First! and The Earth Liberation Front: The rP ogression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America" (2008). Senior Honors Projects. Paper 93. http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/93http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/93 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Greenpeace, Earth First! and The Earth Liberation Front: The Progression of the Radical Environmental Movement in America Christopher John Covill Faculty Sponsor: Professor Timothy Hennessey, Political Science Causes of worldwide environmental destruction created a form of activism, Ecotage with an incredible success rate. Ecotage uses direct action, or monkey wrenching, to prevent environmental destruction. Mainstream conservation efforts were viewed by many environmentalists as having failed from compromise inspiring the birth of radicalized groups. This eventually transformed conservationists into radicals. Green Peace inspired radical environmentalism by civil disobedience, media campaigns and direct action tactics, but remained mainstream. Earth First’s! philosophy is based on a no compromise approach. -

Sustainability Funds Hardly Direct Capital Towards Sustainability

Sustainability Funds Hardly Direct Capital Towards Sustainability Greenpeace-Briefing, original inrate study (pdf) Zurich & Luxembourg, Contact: June 21, 2021 Larissa Marti, Greenpeace Switzerland; Martina Holbach, Greenpeace Luxemburg 2/ 6 As a globalised society in a climate emergency, we need to transition to an economic model that is sustainable and equitable. For societies, industries and corporations to undertake this systemic task of adopting a green and just business model successfully, we need capital – and lots of it. Investors have a choice to make. They can continue to invest in fossil fuels and other carbon-intensive sectors, and by doing so face physical, legal and transition risks1, while exac- erbating the climate crisis. Or they can redirect funding to green companies and projects, thus both contributing to and profiting from a transition to economic sustainability, innovation and job creation. Consumer sentiment appears to encourage the second option. The demand for green financial products has skyrocketed over the past few years and continues to grow. But are sustainable investment funds really able to attract capital and invest them in eco-friendly pro- jects? Can they redirect financial flows into having a positive effect on the environment and our societies? Looking to answer these questions, Greenpeace Switzerland and Greenpeace Luxem- bourg commissioned a study from Inrate, an independent Swiss sustainability rating agency, to investigate whether sustainable investments are actually channelling capital into a sustainable economy. Key findings Sustainability funds in Switzerland and Luxembourg do not sufficiently support the redirection of capital into sustainable activities. The current sustainable investment approaches need to be questioned by all stakeholders. -

Anthropocene Futures: Linking Colonialism and Environmentalism

Special issue article EPD: Society and Space 2020, Vol. 38(1) 111–128 Anthropocene futures: ! The Author(s) 2018 Article reuse guidelines: Linking colonialism and sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI: 10.1177/0263775818806514 environmentalism in journals.sagepub.com/home/epd an age of crisis Bruce Erickson University of Manitoba, Canada Abstract The universal discourse of the Anthropocene presents a global choice that establishes environ- mental collapse as the problem of the future. Yet in its desire for a green future, the threat of collapse forecloses the future as a site for creatively reimagining the social relations that led to the Anthropocene. Instead of examining structures like colonialism, environmental discourses tend to focus instead on the technological innovation of a green society that “will have been.” Through this vision, the Anthropocene functions as a geophysical justification of structures of colonialism in the services of a greener future. The case of the Canadian Boreal Forest Agreement illustrates how this crisis of the future is sutured into mainstream environmentalism. Thus, both in the practices of “the environment in crisis” that are enabled by the Anthropocene and in the discourse of geological influence of the “human race,” colonial structures privilege whiteness in our environmental future. In this case, as in others, ecological protection has come to shape the political life of colonialism. Understanding this relationship between environmen- talism and the settler state in the Anthropocene reminds us that -

What Does Earth Day Mean Today?

Student Worksheet What Does Earth Day Mean Today? http://www.pbs.org/newshour/extra/2013/04/what-does-earth-day-mean-today/ On April 22 of each year people around the world plant trees, commute to work by bicycle and pick up trash in their neighborhoods to observe Earth Day, an event created to shine a spotlight on environmental concerns. The first Earth Day was organized by Gaylord Nelson, a former U.S. senator from Wisconsin, in 1970 as a way to bring environmental protection onto the national political agenda. "It took off like gangbusters. Telegrams, letters, and telephone inquiries poured in from all across the country," Nelson recounted in an essay shortly before he died in 2005. The first Earth Day was a teach-in modeled after the anti-Vietnam War protests. An estimated 20 million people participated. Organizers expect more than a billion people in 192 countries to take part in the 2013 celebrations. Page 1 http://www.pbs.org/newshour/extra Earth Day helped build political support for environmental issues Anger about the environment had been growing since scientist and writer Rachel Carson published ‘Silent Spring’ in 1962. The best-selling book documented the increased use of pesticides and chemicals after World War II, and the effects of pollution on animals and human health. While the first Earth Day was open to anyone who wished to participate, some of the most enthusiastic Earth Day observers were in schools and universities around the country. "We had reports on over 10,000 high schools doing something," said Senator Nelson, "and I personally heard from more than 2,500 colleges and from some 2,000 communities. -

EARTH DAY 1970 - 2015 Earth Day Is an Annual Event, Celebrated on April 22, on Which Day Events Worldwide Are Held to Demonstrate Support for Environmental Protection

APRIL 2015 EARTH DAY 1970 - 2015 Earth Day is an annual event, celebrated on April 22, on which day events worldwide are held to demonstrate support for environmental protection. It was first celebrated in 1970, and is now coordinated globally by the Earth Day Network, and celebrated in more than 192 countries each year. Originally, Earth Day was meant as a teach-in on campuses and April 22nd was late enough in the spring for decent weather, didn’t coincide with Easter or Passover, and prior to exam period. Earth Day activities in 1990 gave a huge boost to recycling efforts worldwide and helped pave the way for the 1992 United Nations Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. Unlike the first Earth Day in 1970, this 20th Anniversary was waged with stronger marketing tools, greater access to television and radio, and multimillion-dollar budgets. Earth Day 2000 was the first year that Earth Day used the Internet as its principal organizing tool, and it proved invaluable nationally and internationally. The event ultimately enlisted more than 5,000 environmental groups outside the United States, reaching hundreds of millions of people in a record 183 countries, with Leonardo DiCaprio as host. 2015 marks 45 years of Earth Day. THE GREAT AMERICAN CLEANUP April 18th is officially the Great American Cleanup and is meant to coincide with Earth Day, however, all of April is full of events for cleaning up our local communities. Opportunities in Palm Beach can be found at: http://www.keeppbcbeautiful.org/monthly.htm and Broward : http://www.broward.org/WasteAndRecycling/Pages/Default.aspx. -

Reducing Meat and Dairy for a Healthier Life and Planet

LESS IS MORE REDUCING MEAT AND DAIRY FOR A HEALTHIER LIFE AND PLANET The Greenpeace vision of the meat and dairy system towards 2050 The Greenpeace vision of the meat and dairy system towards 2050 Foreword This report is based upon “The need already over-consuming meat and milk, to a more detailed technical Foreword the detriment of global human health. These review of the scientific evidence to reduce relating to the environmental Professor Pete Smith levels of consumption are not sustainable. and health implications of the demand for LESS production and consumption We could significantly reduce meat and milk livestock of meat and dairy products: I have been working on the sustainability consumption globally, which would improve Tirado, R., Thompson, K.F., Miller, of agriculture and food systems for over 20 products human health, decrease environmental K.A. & Johnston, P. (2018) Less is more: Reducing meat years, and over this time have been involved is now a impact, help to tackle climate change, and IS MORE and dairy for a healthier life and in hundreds of studies examining how to scientifically feed more people from much less land – REDUCING MEAT AND DAIRY planet - Scientific background reduce the climate impact of agriculture, and perhaps freeing some land for biodiversity on the Greenpeace vision of the how to make the global food system more mainstream conservation. And we do not all need to make FOR A HEALTHIER LIFE meat and dairy system towards sustainable. What I have come to realise over view” the once-and-forever decision to become 2050. Greenpeace Research this period is that our current food system, vegetarian or vegan – reduced consumption AND PLANET Laboratories Technical Report (Review) 03-2018 and its future trajectory, is simply not of meat and milk among people who sustainable, and we need to fundamentally consume “less and better” meat / milk could change the way we produce food if we are have a very significant impact.