Bloom's How to Write About Emily Dickinson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emily Dickinson in Song

1 Emily Dickinson in Song A Discography, 1925-2019 Compiled by Georgiana Strickland 2 Copyright © 2019 by Georgiana W. Strickland All rights reserved 3 What would the Dower be Had I the Art to stun myself With Bolts of Melody! Emily Dickinson 4 Contents Preface 5 Introduction 7 I. Recordings with Vocal Works by a Single Composer 9 Alphabetical by composer II. Compilations: Recordings with Vocal Works by Multiple Composers 54 Alphabetical by record title III. Recordings with Non-Vocal Works 72 Alphabetical by composer or record title IV: Recordings with Works in Miscellaneous Formats 76 Alphabetical by composer or record title Sources 81 Acknowledgments 83 5 Preface The American poet Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), unknown in her lifetime, is today revered by poets and poetry lovers throughout the world, and her revolutionary poetic style has been widely influential. Yet her equally wide influence on the world of music was largely unrecognized until 1992, when the late Carlton Lowenberg published his groundbreaking study Musicians Wrestle Everywhere: Emily Dickinson and Music (Fallen Leaf Press), an examination of Dickinson's involvement in the music of her time, and a "detailed inventory" of 1,615 musical settings of her poems. The result is a survey of an important segment of twentieth-century music. In the years since Lowenberg's inventory appeared, the number of Dickinson settings is estimated to have more than doubled, and a large number of them have been performed and recorded. One critic has described Dickinson as "the darling of modern composers."1 The intriguing question of why this should be so has been answered in many ways by composers and others. -

Download It from Microsoft.'

Writing Portfolio This portfolio is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Creative Writing) by Megan van der Nest November 2011 Abstract This portfolio contains the coursework component of this degree, which consisted of weekly writing assignments in a variety of styles and genres. It also contains extracts from the daily journal kept for the duration of the course, which includes earlier versions of the poems in the main collection, and reflections on the process of writing and editing a collection of poetry. ii Table of Contents Part One: Portfolio 1 7-13 February: Reading Research 1 14-20 February: Poetry 4 21-27 February: Fiction 7 28 February-6 March: Monologue/Dialogue 17 7-13 March: Poetry 21 14-20 March: Poetry 24 21-27 March: Poetry 25 26 March: Project Proposal Freewrite 27 28 March-3 April: Poetry & Story Summary 29 3 April: Book Report 1 31 4-19 April: Fiction 35 11-17 April: Fiction 38 18 April-1May: Poetry 41 2-8 May: Poetry 42 9-15 May: Research at NELM 43 29 May: Book Report 2 46 Part Two: Reflective Journal [extracts] 48 lll Part One: Portfolio 7 - 13 February Reading Research Teacher: Robert Berold It's difficult to find fiction in the library, unless you know exactly what you are looking for. They should keep it all together, and sort it alphabetically, rather than using the Dewey system. I'm sure there's a reason for it- it is an academic library I suppose - but it's not designed for browsing. -

Emily Dickinson Poems Commentary

Emily Dickinson was twenty on 10 December 1850. There are 5 of her poems surviving from 1850-4. Poem 1 F1 ‘Awake ye muses nine’ In Emily’s youth the feast of St Valentine was celebrated not for one day but for a whole week, during which ‘the notes flew around like snowflakes (L27),’ though one year Emily had to admit to her brother Austin that her friends and younger sister had received scores of them, but his ‘highly accomplished and gifted elderly sister (L22)’ had been entirely overlooked. She sent this Valentine in 1850 to Elbridge Bowdoin, her father’s law partner, who kept it for forty years. It describes the law of life as mating, and in lines 29-30 she suggests six possible mates for Bowdoin, modestly putting herself last as ‘she with curling hair.’ The poem shows her sense of fun and skill as a verbal entertainer. Poem 2 [not in F] ‘There is another sky’ On 7 June 1851 her brother Austin took up a teaching post in Boston. Emily writes him letter after letter, begging for replies and visits home. He has promised to come for the Autumn fair on 22 October, and on 17 October Emily writes to him (L58), saying how gloomy the weather has been in Amherst lately, with frosts on the fields and only a few lingering leaves on the trees, but adds ‘Dont think that the sky will frown so the day when you come home! She will smile and look happy, and be full of sunshine then – and even should she frown upon her child returning…’ and then she follows these words with poem 2, although in the letter they are written in prose, not verse. -

Dickinson's Fascicles : a Spectrum of Possibilities / Edited by Paul Crumbley and Eleanor Elson Heginbotham

Dickinson’s Fascicles Dickinson’s Fascicles A Spectrum of Possibilities Edited by Paul Crumbley and Eleanor Elson Heginbotham THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS COLUMBUS Copyright © 2014 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dickinson's fascicles : a spectrum of possibilities / edited by Paul Crumbley and Eleanor Elson Heginbotham. pages cm Summary: "In this volume, a number of senior and emerging Dickinson scholars raise their dispa- rate voices with a particular set of theoretical premises, each selecting specific fascicles for close in- spection. The result is the first practical, balanced, common ground for studying Dickinson's poetry in her own context"— Provided by publisher. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-1259-2 (hardback) — ISBN 0-8142-1259-X (cloth) — ISBN 978-0-8142-9363-8 (cd-rom) 1. Dickinson, Emily, 1830–1886—Criticism, Textual. 2. Dickinson, Emily, 1830–1886—Technique. 3. Dickinson, Emily, 1830–1886—Manuscripts. I. Crumbley, Paul, 1952– editor of compilation. II. Heginbotham, Eleanor Elson, editor of compilation. PS1541.Z5D495 2014 811'.4—dc23 2013049757 Cover design by Janna Thompson-Chordas Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Garamond Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American Nation- al Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS List of Illustrations vii List of -

2002 Thomson Peterson SAT II Literature

About Peterson’s To succeed on your lifelong educational journey, you will need accurate, dependable, and practical tools and resources. That is why Peterson’s is everywhere education happens. Because whenever and however you need education content delivered, you can rely on Peterson’s to provide the information, know-how, and guidance to help you reach your goals. Tools to match the right students with the right school. It’s here. Personalized resources and expert guidance. It’s here. Comprehensive and dependable education content—delivered whenever and however you need it. It’s all here. Editorial Development: Sonya Kapoor Turner For more information, contact Peterson’s, 2000 Lenox Drive, Lawrenceville, NJ 08648; 800-338-3282; or find us on the World Wide Web at www.petersons.com/about. COPYRIGHT © 2002 Peterson’s Previous edition, © 2001 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright herein may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution, or information storage and retrieval systems—without the prior written permission of the publisher. For permission to use material from this text or product, complete the Permission Request Form at http://www.petersons.com/permissions. ISBN 0-7689-0959-7 Printed in the United States of America 10987654321040302 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS “Address to the Graduating Class” from ESSAYS, SPEECHES AND PUBLIC LETTERS by William Faulkner, edited by James B. Meriwether. Copyright 1965 by Random House, Inc. Used by permission of Random House, Inc. and The Random House Group Ltd. “The Soul selects her own Society” reprinted by permission of the publishers and the Trustees of Amherst College from THE POEMS OF EMILY DICKINSON, Thomas H. -

Music in the Life and Poetry of Emily Dickinson

MUSIC IN THE LIFE AND POBTRY OF EMILY DICKINSON APPROVED: /3, Maj or Proiess;pr Minor Professor <?. ST. G-tMfv -n Cfiairman "of~t3ie/T)epartifient "of EngiTtsTT" Dean ToF the Graduate SclToo 1 Reglin, Louise W., Music in the Life and Poetry of Emily Dickdrison. Master of Arts (English), August, 1971, 132 pp., appendix, bibliography, 42 titles. The problem with which this study is concerned is the importance of music in the life and poetry of Emily Dickin- son. The means of determining this importance were as follows: (1) determining the experiences which the poet had in music as the background for her references to music in the poems, (2) revealing the extent to which she used the yocao* ulary of music in her poems, (3) explicating the poems whose main subject is music, (4) investigating her use of music in I| the development of certain major themes, and (5) examining! other imagery in her poetry which is related to music. The most often quoted sources of information are The Letters of Emily Dickinson, edited by Thomas H. Johnson, arid The Poems of Emily Dickinson, also edited by Thomas H. John- son. A third work which is of great importance to this study is A Concordance to the Poems of Emily Dickinson by Samuel P. Rosenbaum. The study reveals significant facts about Emily Dickiii" son's life including a description of the village of Amherst, the members of her family, her schooling, her withdrawal j from community life, the fact that she was a private poet, her death, the finding of the hoard of poems by her sister Lavinia, the circumstances surrounding the first publications of poems and letters, and the events which led to a cessation if - „ in their publication." . -

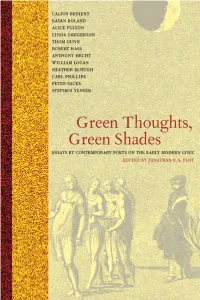

Edited by Jonathan FS Post

2208_FM.qrk 10/4/01 8:29 AM Page i Green Thoughts,Green Shades 2208_FM.qrk 10/4/01 8:29 AM Page ii 2208_FM.qrk 10/4/01 8:29 AM Page iii Green Thoughts, Green Shades essays by contemporary poets on the early modern lyric Edited by Jonathan F.S.Post university of california press berkeley los angeles london 2208_FM.qrk 10/4/01 8:29 AM Page iv University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2002 by the Regents of the University of California A slightly different version of chapter 9 appeared in Alice Fulton, Feeling as a Foreign Language: The Good Strange- ness of Poetry (St. Paul, Minn.: Graywolf Press, 1999), 85–124. James Merrill’s poem “Tomorrows” appears in chapter 2 by kind permission of Random House, Inc., publisher of James Merrill, Collected Poems, ed. by J. D. McClatchy and Stephen Yenser (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2001). Elizabeth Bishop’s poems “A Miracle for Breakfast” and “Sestina” appear in chapter 2, from Elizabeth Bishop, The Complete Poems: 1927–1979. Copyright © 1979, 1983 by Alice Helen Methfessel. Reprinted by permission of Far- rar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Green thoughts, green shades : essays by contemporary poets on the early modern lyric / Jonathan F. S. Post, edi- tor. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-21455-2 (alk. paper).—ISBN 0-520-22752-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. English poetry—Early modern, 1500–1700—History and criticism. I. -

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick As a Poet

bathroom songs Before you start to read this book, take this moment to think about making a donation to punctum books, an independent non-profit press, @ https://punctumbooks.com/support/ If you’re reading the e-book, you can click on the image below to go directly to our donations site. Any amount, no matter the size, is appreciated and will help us to keep our ship of fools afloat. Contri- butions from dedicated readers will also help us to keep our commons open and to cultivate new work that can’t find a welcoming port elsewhere. Our ad- venture is not possible without your support. Vive la open-access. Fig. 1. Hieronymus Bosch, Ship of Fools (1490–1500) bathroom songs: eve kosofsky sedgwick as a poet. Copyright © 2017 by editor and authors. This work carries a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 In- ternational license, which means that you are free to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, and you may also remix, transform and build upon the material, as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors (but not in a way that suggests the authors or punctum books endorses you and your work), you do not use this work for commercial gain in any form whatsoever, and that for any remixing and transformation, you distribute your rebuild under the same license. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ First published in 2017 by punctum books, Earth, Milky Way. https://punctumbooks.com ISBN-13: 978-1-947447-30-1 (print) ISBN-13: 978-1-947447-31-8 (ePDF) lccn: 2017957440 Library of Congress Cataloging Data is available from the Library of Congress Book design: Vincent W.J.