RAFTERS AS PATHS in Discussing the Now Obsolete House Type of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saint Gayane Church

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Seminář dějin umění Saint Gayane Church Bakalárska diplomová práca Autor: Michaela Baraničová Vedúci práce: prof. Ivan Foletti, MA, Docteur es Lettres Brno 2020 ii Prehlasujem, že som svoju bakalársku diplomovú prácu vypracovala samostatne a uviedla všetkú použitú literatúru a pramene. .............................................................. Podpis autora práce iii iv On the ancient peak of Ararat The centuries have come like seconds, And passed on. The swords of innumerable lightnings Have broken upon its diamond crest, And passed on. The eyes of generations dreading death Have glanced at its luminuos summit, And passed on. The turn is now yours for a brief while: You, too, look at its lofty brow, And pass on! Avetik Isahakyan, “Mount Ararat”, in Selected Works: Poetry and Prose, ed. M. Kudian, Moscow 1976. v vi My first sincere thanks belong to my thesis’ supervisor, prof. Ivan Foletti, for his observations, talks and patience during this time. Especially, I would like to thank him for introducing me to the art of Caucasus and giving me the opportunity to travel to Armenia for studies, where I spent five exciting months. I would like to thank teachers from Yerevan State Academy of Arts, namely to Gayane Poghosyan and Ani Yenokyan, who were always very kind and helped me with better access of certain Armenian literature. My gratitude also belongs to my friends Susan and colleagues, notably to Veronika, who was with me in Armenia and made the whole experience more entertaining. To Khajag, who helped me with translation of Armenian texts and motivating me during the whole process. It´s hard to express thanks to my amazing parents, who are constantly supporting me in every step of my studies and life, but let me just say: Thank you! vii viii Content Introduction.........................................................................1 I. -

Design Guidelines September, 1999 Table of Contents

Design Guidelines September, 1999 Table of Contents I: Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 A. Preserving the Architectural Heritage............................................................................................................................................. 1 B. History of the Historic District Area............................................................................................................................................... 1 C. Other Areas of Historical Significance........................................................................................................................................... 2 D. Historic Preservation Commission................................................................................................................................................. 3 E. Purpose............................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 F. Scope and Jurisdiction .................................................................................................................................................................... 4 G. Certificate of Appropriateness ....................................................................................................................................................... -

Roofing Systems Overview Double Lock Standing Seam

Roofng systems overview Double lock standing seam Roofng systems overview – Double lock standing seam | 3 Sistemas de revestimiento - Junta alzada para fachadas Index Main characteristics 5 Principal joints 6 Cross joints 7 Fixing 8 Standing seam tray dimensions 9 Installation 10 Appearance 10 Rainwater drainage 11 Roof shapes 12 Substrates and roof construction 14 Summary 16 Samples 17 4 | Roofng systems overview – Double lock standing seam Roofng systems overview – Double lock standing seam | 5 Main characteristics The double lock standing seam system provides a lightweight, sustainable and very durable roofing solution and is commonly used on many different building types including educational, healthcare, sports, comercial, religious and, of course, housing. The system is suitable for roofs pitched between 3º and 90º, barrel vaulted roofs, conical and domed roofs, and in general almost any type of roof that can be clad in elZinc®. This is a proven traditional system that has been used to install zinc since the origins of zinc roofing itself and continues to be by far the most popular method today. The fine lines of the standing seams give the system its light, attractive appearance and contribute to its flexibility. Modern profiling and seaming technology makes quick work of large roo- fs, decreasing installation times and the associated direct and indirect costs. It can be installed over a ventilated or non-ventila- ted roof construction, allowing the best solution to be chosen according to the characteristics of each project. The fixing is hidden and indirect. It needs a continuous support behind it and normally uses elZinc® sheet thicknesses of between 0.65 and 0.8mm. -

Elements of Construction

149 Chapter 8 Elements of construction INTRODUCTION mass of these loads can be calculated readily, the fact When designing a building, an architect plans for that the number or amount of components may vary spatial, environmental and visual requirements. Once considerably from time to time makes live loads more these requirements are satisfied, it is necessary to detail difficult to estimate than dead loads. Live loads also the fabric of the building. The choice of materials and include the forces resulting from natural phenomena, the manner in which they are put together to form such as wind, earthquakes and snow. building elements, such as the foundation, walls, floor Where wind velocities have been recorded, the and roof, depend largely upon their properties relative following equation can be used to determine the expected to environmental requirements and their strength. pressures on building walls: The process of building construction thus involves an understanding of: the nature and characteristics of q = 0.0127 V2k a number of materials; the methods to process them and form them into building units and components; where: structural principles; stability and behaviour under q = basic velocity pressure (Pa) load; building production operations; and building V = wind velocity (m/s) economics. k = (h/6.1)2/7 The limited number of materials available in the h = design height of building, in metres (eave height for rural areas of Africa has resulted in a limited number of low and medium roof pitches) structural forms and methods of construction. Different 6.1 = height at which wind velocities were often recorded socio-economic conditions and cultural beliefs are for Table 8.1. -

Study Guide for How to Perform Roof Inspections Course

Study Guide for How to Perform Roof Inspections Course This study guide can help you: • take notes; • read and study offline; • organize information; and • prepare for assignments and assessments. As a member of InterNACHI, you may check your education folder, transcript, and course completions by logging into your Members-Only Account at www.nachi.org/account. To purchase textbooks (printed and electronic), visit InterNACHI’s ecommerce partner Inspector Outlet at www.inspectoroutlet.com. Copyright © 2007-2015 International Association of Certified Home Inspectors, Inc. Page 1 of 106 Page 2 of 106 Student Verification & Interactivity Student Verification By enrolling in this course, the student hereby attests that s/he is the person completing all coursework. S/he understands that having another person complete the coursework for him or her is fraudulent and will result in being denied course completion and corresponding credit hours. The course provider reserves the right to make contact as necessary to verify the integrity of any information submitted or communicated by the student. The student agrees not to duplicate or distribute any part of this copyrighted work or provide other parties with the answers or copies of the assessments that are part of this course. If plagiarism or copyright infringement is proven, the student will be notified of such and barred from the course and/or have his/her credit hours and/or certification revoked. Communication on the message board or forum shall be of the person completing all coursework. Page 3 of 106 Introduction to Course Introduction to Roof Inspections An inspection of the roof system is both one of the most crucial areas of home inspection and one of the biggest concerns on the prospective home buyer's mind. -

Armenia – Georgia – Islam: a Need to Break Taboos in the Study of Medieval Architecture

Armenia – Georgia – Islam : A Need to Break Taboos in the Study of Medieval Architecture Patrick Donabédian To cite this version: Patrick Donabédian. Armenia – Georgia – Islam : A Need to Break Taboos in the Study of Medieval Architecture. Aldo Ferrari; Stefano Riccioni; Marco Ruffilli; Beatrice Spampinato. L’arte armena : Storia critica e nuove prospettive Studies in Armenian and Eastern Christian Art 2020, 16, Edizioni Ca’ Foscari - Digital Publishing, pp.62-112, 2020, Eurasiatica, 978-88-6969-495-0. 10.30687/978-88- 6969-469-1/005. halshs-03177703 HAL Id: halshs-03177703 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03177703 Submitted on 23 Mar 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. L’arte armena. Storia critica e nuove prospettive Studies in Armenian and Eastern Christian Art 2020 a cura di Aldo Ferrari, Stefano Riccioni, Marco Ruffilli, Beatrice Spampinato Armenia – Georgia – Islam A Need to Break Taboos in the Study of Medieval Architecture Patrick Donabédian Aix Marseille Université, CNRS, LA3M, Aix-en-Provence, France Abstract Two important spheres of the history of medieval architecture in the Ana- tolia-Armenia-South-Caucasian region remain insufficiently explored due to some kind of taboos that still hinder their study. -

Part II: Historic Homes

Pa r t II ● De s I g n gu id e l I n e s f o r al t e r a t I o n s & addi t I o n s t o HI s t o r I c re s id e n c e s ● Pa r t II: De s I g n gu id e l I n e s f o r al t e r a t I o n & addi t I o n s t o HI s t o r I c re s id e n c e s ● 7 D ESIGN GUI D ELINES FOR ALTER A TIONS A N D Add ITIONS TO HISTORIC RESI D ENCES ta b l e o f co n t e n t s P a r t II ● Overview of Typical Historical Residential Styles of Architecture Introduction............................................................................................... 9 Craftsman / Bungalow............................................................................... 10 Mission and Spanish Colonial Revival...................................................... 12 Turn of the Century (Queen Anne, Shingle, Foursquare, Farmhouse Vernacular)................................................................................................ 14 American Colonial Revival........................................................................ 16 Tudor and English Inspired....................................................................... 18 French Inspired (French Revival and Norman Revival)............................ 20 Monterey Revival...................................................................................... 22 Other Styles.............................................................................................. 24 Alterations to Primary Facades of Historic Residential Buildings Introduction.............................................................................................. -

The World Leader in Cold-Formed Steel Trusses

2016 Trussteel DesMan Cov_Layout 1 4/7/17 9:53 AM Page 1 STEEL TRUSS DESIGN MANUAL STEEL ENGINEERED BY ALPINE The World Leader 888.565.9181 • www.TrusSteel.com in Cold-Formed Steel Trusses Steel Truss 05 44 00 Cold Formed Metal Trusses 05 44 00 Cold Formed Metal Trusses Design Manual TRUSS DESIGN MANUAL ENGINEERED BY ALPINE TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 OVERVIEW 4 ENGINEERING / SHOP DRAWINGS 1.01 Introduction 4.01 Engineering 1.02 Specifiers & Designers 4.03 Shop Drawings 1.03 Contractor & Installer 4.04 Notes Page 1.04 Truss Components & Code Recognition 1.05 Framing & Connections 5 DETAILS / CONNECTIONS 1.06 Authorized TrusSteel Fabricators 5.01 Overview 1.07 Education & CES 5.03 Standard Details 1.08 Notes Page 5.04 Truss-to-Truss Connections 5.06 Gable Outlooker Connections 2 APPLICATIONS 5.07 Truss-to-Bearing Connections 2.01 Applications 5.13 Piggyback and Valley Truss Connections 2.02 Projects 6 TRUSS FABRICATION / QUALITY 3 SPECIFYING / DESIGNING 6.01 Overview 3.01 Overview 3.02 Building Codes & Design Standards 7 INSTALLATION / BRACING 3.03 Information Required for Truss Design 7.01 Site Conditions & Safety 3.05 TrusSteel System 7.02 Handling & Storage 3.07 Wind Loading 7.03 Lifting & Staging 3.10 Snow Loading 7.04 Bracing 3.11 Seismic Loading 7.05 Rafting 3.13 Sound Control 3.14 Sustainability & LEED 8 REFERENCES / RESOURCES 3.15 Fire Resistance & UL 8.01 Industry Resources 3.16 Trusses as Building Components 8.02 Glossary 3.17 Roof Truss Systems - Framing 8.07 Weights of Materials 3.22 Roof Truss Systems - Sample Spans 3.23 Floor Truss Systems 3.26 Guide Specifications © Copyright 2016 Alpine TrusSteel This Design Manual is intended as a guide to building professionals for suggested uses of TrusSteel trusses. -

RECEIVED National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 14-bOU (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior RECEIVED National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties anc National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Comf )ox or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being docu nelriisip P' For fun itions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and s entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property ___•, • • ___• ' •••'•' '' .•••••____'. __________________ historic name Emerson Coulson House_______________________________ other names/site number 041-0020-0030 2. Location street & number D not for publication city or town Abilene _ D vicinity state Kansas code 041 zip code 67410 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this OS nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property S meets O does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant nationally D statewide 13 locally. (D SeeContinuation sheet for additional comments.) SHPO_____January 31, 1995 jnature of certifying official/Title Date Kansas State Historical Society_____________________________ In my opinion, the property D meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Comparison of Microburst-Wind Loads on Low-Rise Structures of Various Geometric Shapes

J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 133 (2014) 181–190 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jweia Comparison of microburst-wind loads on low-rise structures of various geometric shapes Yan Zhang, Hui Hu, Partha P. Sarkar n Department of Aerospace Engineering, Iowa State University, 2271 Howe Hall, Ames, IA 50011, USA article info abstract Microburst can produce downdraft and strong divergent outflow wind, whose characteristics are distinct Keywords: from the atmospheric boundary layer (ABL) wind. In the present study, microburst-wind loading effects Microburst-wind effects on low-rise structures À a cubic-shaped building, a grain bin and two gable-roofed buildings – are Low-rise buildings evaluated and compared by performing laboratory tests on scaled models using a microburst simulator Surface pressures at Iowa State University. Velocity and turbulence intensity profiles at selected locations were studied. Wind loads The distribution of mean and root-mean-square pressure coefficients for the models are shown for Comparison with ABL wind selected cases and compared with those obtained in the ABL wind. Results suggest that wind loads change significantly as the radial location, orientation and geometric shape of the structures vary. It was observed that at or near the center of the microburst, high external pressures occur for all structures, resulting in a large downward force on the roof. In the outburst region, the distribution of pressure coefficients on the structure envelope was found to be similar to those in the ABL wind, although actual wind load magnitudes may be much larger in the microburst wind. -

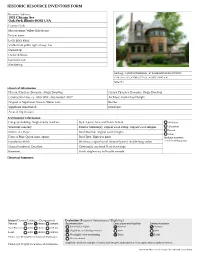

Historic Resource Inventory Form

HISTORIC RESOURCE INVENTORY FORM Resource Address: 1031 Chicago Ave Oak Park Illinois 60302 USA County: Cook Historic name: Walter Gale House Present name: Local place name: Visible from public right of way: Yes Ownership: Owner/Address: Land unit size: Site/Setting: Lat/Long: 41.8939529283655600, -87.8018696822090300 [WGS84] UTM: Zone 16T, 433480.6732 mE, 4638312.8847 mN Parcel No. Historical Information Historic Function: Domestic: Single Dwelling Current Function: Domestic: Single Dwelling Construction Date: ca. 1890-1899 , documented 1893* Architect: Frank Lloyd Wright Original or Significant Owners: Walter Gale Builder: Significant Date/Period: Developer: Areas of Significance: Architectural Information Category: building, Single-family residence Style: Queen Anne and Prairie School Additions Structural: masonry Exterior Material(s): original wood siding, original wood shingles Alterations Moved Stories: 2.5, Bays: Roof Material: original wood shingles Other Form or Plan: Queen Anne, square Roof Type: High side gable Ancillary structures: Foundation: Brick Windows: original wood Diamond pane/1 double-hung sashes 1 total including garage General condition: Excellent Chimney(s): one brick Front front slope Basement: Porch: single-story Full-width veranda Historical Summary: Status (Current Listing or Designation) Evaluation (Preparer's Assessment of Eligibility) National: indiv. district landmrk. Recommendation Level of potential eligibility Landmark potential State/Province: indiv. district landmrk. Individually eligible National National Eligible as contributing resource State State Local: indiv. district landmrk. Not eligible / non-contributing Local Local Frank Lloyd Wright-Prairie School of Architecture Not determined Eligibility: Excellent example of Frank Lloyd Wright's early transition from Queen Anne towards the Prairie… Frank Lloyd Wright-Prairie School of Architecture Inventory Sheet : 1031 Chicago Ave Oak Park Cook Illinois 1031 Chicago Ave Oak Park, Illinois (pg. -

The Structural Behaviour of Spires

Structural Analysis of Historic Construction – D’Ayala & Fodde (eds) © 2008 Taylor & Francis Group, London, ISBN 978-0-415-46872-5 The structural behaviour of spires E. Olosz & B. Szabó Technical University, Cluj-N., Romania ABSTRACT: In spite of the fact that there are plenty of examples of historic spatial roof structures – in spires, castle towers, etc. – in the technical literature information about this kind of structure can rarely be found, especially about their structural behaviour. The development of computerised 3D programs of analysis and modelling helped us to improve our understanding of this. This paper offers a guide to assist in the understanding of the structural behaviour of the load bearing structure of spires, offering a typology, followed by a detailed presentation of these structural analyses. 1 INTRODUCTION exclusively from supporting load-bearing sub-units (such as walls, pillars, columns), usually located on To build a shelter against sun, wind or rain is one of the external face or edge of buildings [6]. the most fundamental of human needs. Since the earli- Spatial system: the spatial system of a historic est times, people have joined together pieces of wood, roof structure is formed from different load-bearing forming the first spatial structures – conical timber structural materials (hardwood or softwood timber) huts or dwellings. Later on, the construction of tow- connected by joints between lineal elements, so form- ers of fortifications and churches continued the still ing a stable truss system. The spatial systems of a ongoing development of spatial roof structures. historic roof structure can either be jointed together Following technical development over centuries, with frames (particularly if the layout is rectangular), architectural styles also had their remarks on spatial or it is a real spatial system, which cannot be divided roof structures.