Near-Surface Temperatures on Mercury and the Moon and the Stability of Polar Ice Deposits1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ices on Mercury: Chemistry of Volatiles in Permanently Cold Areas of Mercury’S North Polar Region

Icarus 281 (2017) 19–31 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Icarus journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/icarus Ices on Mercury: Chemistry of volatiles in permanently cold areas of Mercury’s north polar region ∗ M.L. Delitsky a, , D.A. Paige b, M.A. Siegler c, E.R. Harju b,f, D. Schriver b, R.E. Johnson d, P. Travnicek e a California Specialty Engineering, Pasadena, CA b Dept of Earth, Planetary and Space Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, CA c Planetary Science Institute, Tucson, AZ d Dept of Engineering Physics, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA e Space Sciences Laboratory, University of California, Berkeley, CA f Pasadena City College, Pasadena, CA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Observations by the MESSENGER spacecraft during its flyby and orbital observations of Mercury in 2008– Received 3 January 2016 2015 indicated the presence of cold icy materials hiding in permanently-shadowed craters in Mercury’s Revised 29 July 2016 north polar region. These icy condensed volatiles are thought to be composed of water ice and frozen Accepted 2 August 2016 organics that can persist over long geologic timescales and evolve under the influence of the Mercury Available online 4 August 2016 space environment. Polar ices never see solar photons because at such high latitudes, sunlight cannot Keywords: reach over the crater rims. The craters maintain a permanently cold environment for the ices to persist. Mercury surface ices magnetospheres However, the magnetosphere will supply a beam of ions and electrons that can reach the frozen volatiles radiolysis and induce ice chemistry. -

Project Selene: AIAA Lunar Base Camp

Project Selene: AIAA Lunar Base Camp AIAA Space Mission System 2019-2020 Virginia Tech Aerospace Engineering Faculty Advisor : Dr. Kevin Shinpaugh Team Members : Olivia Arthur, Bobby Aselford, Michel Becker, Patrick Crandall, Heidi Engebreth, Maedini Jayaprakash, Logan Lark, Nico Ortiz, Matthew Pieczynski, Brendan Ventura Member AIAA Number Member AIAA Number And Signature And Signature Faculty Advisor 25807 Dr. Kevin Shinpaugh Brendan Ventura 1109196 Matthew Pieczynski 936900 Team Lead/Operations Logan Lark 902106 Heidi Engebreth 1109232 Structures & Environment Patrick Crandall 1109193 Olivia Arthur 999589 Power & Thermal Maedini Jayaprakash 1085663 Robert Aselford 1109195 CCDH/Operations Michel Becker 1109194 Nico Ortiz 1109533 Attitude, Trajectory, Orbits and Launch Vehicles Contents 1 Symbols and Acronyms 8 2 Executive Summary 9 3 Preface and Introduction 13 3.1 Project Management . 13 3.2 Problem Definition . 14 3.2.1 Background and Motivation . 14 3.2.2 RFP and Description . 14 3.2.3 Project Scope . 15 3.2.4 Disciplines . 15 3.2.5 Societal Sectors . 15 3.2.6 Assumptions . 16 3.2.7 Relevant Capital and Resources . 16 4 Value System Design 17 4.1 Introduction . 17 4.2 Analytical Hierarchical Process . 17 4.2.1 Longevity . 18 4.2.2 Expandability . 19 4.2.3 Scientific Return . 19 4.2.4 Risk . 20 4.2.5 Cost . 21 5 Initial Concept of Operations 21 5.1 Orbital Analysis . 22 5.2 Launch Vehicles . 22 6 Habitat Location 25 6.1 Introduction . 25 6.2 Region Selection . 25 6.3 Locations of Interest . 26 6.4 Eliminated Locations . 26 6.5 Remaining Locations . 27 6.6 Chosen Location . -

Bepicolombo - a Mission to Mercury

BEPICOLOMBO - A MISSION TO MERCURY ∗ R. Jehn , J. Schoenmaekers, D. Garc´ıa and P. Ferri European Space Operations Centre, ESA/ESOC, Darmstadt, Germany ABSTRACT BepiColombo is a cornerstone mission of the ESA Science Programme, to be launched towards Mercury in July 2014. After a journey of nearly 6 years two probes, the Magneto- spheric Orbiter (JAXA) and the Planetary Orbiter (ESA) will be separated and injected into their target orbits. The interplanetary trajectory includes flybys at the Earth, Venus (twice) and Mercury (four times), as well as several thrust arcs provided by the solar electric propulsion module. At the end of the transfer a gravitational capture at the weak stability boundary is performed exploiting the Sun gravity. In case of a failure of the orbit insertion burn, the spacecraft will stay for a few revolutions in the weakly captured orbit. The arrival conditions are chosen such that backup orbit insertion manoeuvres can be performed one, four or five orbits later with trajectory correction manoeuvres of less than 15 m/s to compensate the Sun perturbations. Only in case that no manoeuvre can be performed within 64 days (5 orbits) after the nominal orbit insertion the spacecraft will leave Mercury and the mission will be lost. The baseline trajectory has been designed taking into account all operational constraints: 90-day commissioning phase without any thrust; 30-day coast arcs before each flyby (to allow for precise navigation); 7-day coast arcs after each flyby; 60-day coast arc before orbit insertion; Solar aspect angle constraints and minimum flyby altitudes (300 km at Earth and Venus, 200 km at Mercury). -

The Search for Another Earth – Part II

GENERAL ARTICLE The Search for Another Earth – Part II Sujan Sengupta In the first part, we discussed the various methods for the detection of planets outside the solar system known as the exoplanets. In this part, we will describe various kinds of exoplanets. The habitable planets discovered so far and the present status of our search for a habitable planet similar to the Earth will also be discussed. Sujan Sengupta is an 1. Introduction astrophysicist at Indian Institute of Astrophysics, Bengaluru. He works on the The first confirmed exoplanet around a solar type of star, 51 Pe- detection, characterisation 1 gasi b was discovered in 1995 using the radial velocity method. and habitability of extra-solar Subsequently, a large number of exoplanets were discovered by planets and extra-solar this method, and a few were discovered using transit and gravi- moons. tational lensing methods. Ground-based telescopes were used for these discoveries and the search region was confined to about 300 light-years from the Earth. On December 27, 2006, the European Space Agency launched 1The movement of the star a space telescope called CoRoT (Convection, Rotation and plan- towards the observer due to etary Transits) and on March 6, 2009, NASA launched another the gravitational effect of the space telescope called Kepler2 to hunt for exoplanets. Conse- planet. See Sujan Sengupta, The Search for Another Earth, quently, the search extended to about 3000 light-years. Both Resonance, Vol.21, No.7, these telescopes used the transit method in order to detect exo- pp.641–652, 2016. planets. Although Kepler’s field of view was only 105 square de- grees along the Cygnus arm of the Milky Way Galaxy, it detected a whooping 2326 exoplanets out of a total 3493 discovered till 2Kepler Telescope has a pri- date. -

CALIFORNIA's NORTH COAST: a Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors

CALIFORNIA'S NORTH COAST: A Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors. A Geographically Arranged Bibliography focused on the Regional Small Presses and Local Authors of the North Coast of California. First Edition, 2010. John Sherlock Rare Books and Special Collections Librarian University of California, Davis. 1 Table of Contents I. NORTH COAST PRESSES. pp. 3 - 90 DEL NORTE COUNTY. CITIES: Crescent City. HUMBOLDT COUNTY. CITIES: Arcata, Bayside, Blue Lake, Carlotta, Cutten, Eureka, Fortuna, Garberville Hoopa, Hydesville, Korbel, McKinleyville, Miranda, Myers Flat., Orick, Petrolia, Redway, Trinidad, Whitethorn. TRINITY COUNTY CITIES: Junction City, Weaverville LAKE COUNTY CITIES: Clearlake, Clearlake Park, Cobb, Kelseyville, Lakeport, Lower Lake, Middleton, Upper Lake, Wilbur Springs MENDOCINO COUNTY CITIES: Albion, Boonville, Calpella, Caspar, Comptche, Covelo, Elk, Fort Bragg, Gualala, Little River, Mendocino, Navarro, Philo, Point Arena, Talmage, Ukiah, Westport, Willits SONOMA COUNTY. CITIES: Bodega Bay, Boyes Hot Springs, Cazadero, Cloverdale, Cotati, Forestville Geyserville, Glen Ellen, Graton, Guerneville, Healdsburg, Kenwood, Korbel, Monte Rio, Penngrove, Petaluma, Rohnert Part, Santa Rosa, Sebastopol, Sonoma Vineburg NAPA COUNTY CITIES: Angwin, Calistoga, Deer Park, Rutherford, St. Helena, Yountville MARIN COUNTY. CITIES: Belvedere, Bolinas, Corte Madera, Fairfax, Greenbrae, Inverness, Kentfield, Larkspur, Marin City, Mill Valley, Novato, Point Reyes, Point Reyes Station, Ross, San Anselmo, San Geronimo, San Quentin, San Rafael, Sausalito, Stinson Beach, Tiburon, Tomales, Woodacre II. NORTH COAST AUTHORS. pp. 91 - 120 -- Alphabetically Arranged 2 I. NORTH COAST PRESSES DEL NORTE COUNTY. CRESCENT CITY. ARTS-IN-CORRECTIONS PROGRAM (Crescent City). The Brief Pelican: Anthology of Prison Writing, 1993. 1992 Pelikanesis: Creative Writing Anthology, 1994. 1994 Virtual Pelican: anthology of writing by inmates from Pelican Bay State Prison. -

Mariner to Mercury, Venus and Mars

NASA Facts National Aeronautics and Space Administration Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Pasadena, CA 91109 Mariner to Mercury, Venus and Mars Between 1962 and late 1973, NASA’s Jet carry a host of scientific instruments. Some of the Propulsion Laboratory designed and built 10 space- instruments, such as cameras, would need to be point- craft named Mariner to explore the inner solar system ed at the target body it was studying. Other instru- -- visiting the planets Venus, Mars and Mercury for ments were non-directional and studied phenomena the first time, and returning to Venus and Mars for such as magnetic fields and charged particles. JPL additional close observations. The final mission in the engineers proposed to make the Mariners “three-axis- series, Mariner 10, flew past Venus before going on to stabilized,” meaning that unlike other space probes encounter Mercury, after which it returned to Mercury they would not spin. for a total of three flybys. The next-to-last, Mariner Each of the Mariner projects was designed to have 9, became the first ever to orbit another planet when two spacecraft launched on separate rockets, in case it rached Mars for about a year of mapping and mea- of difficulties with the nearly untried launch vehicles. surement. Mariner 1, Mariner 3, and Mariner 8 were in fact lost The Mariners were all relatively small robotic during launch, but their backups were successful. No explorers, each launched on an Atlas rocket with Mariners were lost in later flight to their destination either an Agena or Centaur upper-stage booster, and planets or before completing their scientific missions. -

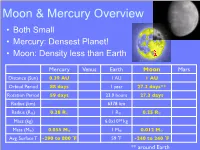

Moon & Mercury Overview

Moon & Mercury Overview • Both Small • Mercury: Densest Planet! • Moon: Density less than Earth Mercury Venus Earth Moon Mars Distance (Sun) 0.39 AU 1 AU 1 AU Orbital Period 88 days 1 year 27.3 days** Rotation Period 59 days 23.9 hours 27.3 days Radius (km) 6378 km Radius (R⊕) 0.38 R⊕ 1 R⊕ 0.25 R⊕ Mass (kg) 6.0x1024 kg Mass (M⊕) 0.055 M⊕ 1 M⊕ 0.012 M⊕ Avg. Surface T -290 to 800 F̊ 59 F̊ -240 to 240 F̊ ** around Earth Lunar Surface • Cratered – 30,000 big (> 1km) – millions of smaller craters MercurianMercury Surface - Surface Features Messenger Images Era of Heavy Bombardment Period of intense impacts in the inner S.S. by leftover planetesimals from outer S.S. 4.1-3.8 billion yrs ago affects all Terr. planets Lunar Surface • Dark Maria (“Seas”) • Lighter Highlands (“Lands”, Terrae) Lunar Surface • Maria What’s different? Why? • Highlands Apollo Lunar Surface Maria: smooth, flat, fewer craters Highlands: VERY cratered Maria have been resurfaced! Maria Formation After Heavy Bombardment Volcanic Activity caused by heat from radioactive decay flooded old craters Dating the Lunar Surface Crater Counting! Which is oldest? The Moon - Space Exploration • Luna 3 (Russia), 1959 Luna 3 farside • NASA Rangers (Impactors), 1961-1965 • Orbiters (99% mapped), 1966-1967 • Surveyors (landers), 1966-1968 • Apollo (manned), 1968-1972 • Clementine (Multi-wavel. mapping), 1994 • Prospector (polar orbiter), 1998 • SMART-1 (ESA Impactor), 2003-2006 • Kaguya (Japan), 2007- Prospector • Chang-e 1 (China), 2007- • Chandrayaan (India), 2008- Orbiter • Lunar Recon. -

The Composition of Planetary Atmospheres 1

The Composition of Planetary Atmospheres 1 All of the planets in our solar system, and some of its smaller bodies too, have an outer layer of gas we call the atmosphere. The atmosphere usually sits atop a denser, rocky crust or planetary core. Atmospheres can extend thousands of kilometers into space. The table below gives the name of the kind of gas found in each object’s atmosphere, and the total mass of the atmosphere in kilograms. The table also gives the percentage of the atmosphere composed of the gas. Object Mass Carbon Nitrogen Oxygen Argon Methane Sodium Hydrogen Helium Other (kilograms) Dioxide Sun 3.0x1030 71% 26% 3% Mercury 1000 42% 22% 22% 6% 8% Venus 4.8x1020 96% 4% Earth 1.4x1021 78% 21% 1% <1% Moon 100,000 70% 1% 29% Mars 2.5x1016 95% 2.7% 1.6% 0.7% Jupiter 1.9x1027 89.8% 10.2% Saturn 5.4x1026 96.3% 3.2% 0.5% Titan 9.1x1018 97% 2% 1% Uranus 8.6x1025 2.3% 82.5% 15.2% Neptune 1.0x1026 1.0% 80% 19% Pluto 1.3x1014 8% 90% 2% Problem 1 – Draw a pie graph (circle graph) that shows the atmosphere constituents for Mars and Earth. Problem 2 – Draw a pie graph that shows the percentage of Nitrogen for Venus, Earth, Mars, Titan and Pluto. Problem 3 – Which planet has the atmosphere with the greatest percentage of Oxygen? Problem 4 – Which planet has the atmosphere with the greatest number of kilograms of oxygen? Problem 5 – Compare and contrast the objects with the greatest percentage of hydrogen, and the least percentage of hydrogen. -

Investigating the Neutral Sodium Emissions Observed at Comets

Investigating the neutral sodium emissions observed at comets K. S. Birkett M.Sci. Physics, Imperial College London, UK (2012) Department of Space and Climate Physics University College London Mullard Space Science Laboratory, Holmbury St. Mary, Dorking, Surrey. RH5 6NT. United Kingdom THESIS Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University College London 2017 2 I, Kimberley Si^anBirkett, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Abstract Neutral sodium emission is typically very easy to detect in comets, and has been seen to form a distinct neutral sodium tail at some comets. If the source of neutral cometary sodium could be determined, it would shed light on the composition of the comet, therefore allowing deeper understanding of the conditions present in the early solar system. Detection of neutral sodium emission at other solar system objects has also been used to infer chemical and physical processes that are difficult to measure directly. Neutral cometary sodium tails were first studied in depth at comet Hale-Bopp, but to date the source of neutral sodium in comets has not been determined. Many authors considered that orbital motion may be a significant factor in conclusively identifying the source of neutral sodium, so in this work details of the development of the first fully heliocentric distance and velocity dependent orbital model, known as COMPASS, are presented. COMPASS is then applied to a range of neutral sodium observations, includ- ing spectroscopic measurements at comet Hale-Bopp, wide field images of comet Hale- Bopp, and SOHO/LASCO observations of neutral sodium tails at near-Sun comets. -

Lick Observatory Records: Photographs UA.036.Ser.07

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c81z4932 Online items available Lick Observatory Records: Photographs UA.036.Ser.07 Kate Dundon, Alix Norton, Maureen Carey, Christine Turk, Alex Moore University of California, Santa Cruz 2016 1156 High Street Santa Cruz 95064 [email protected] URL: http://guides.library.ucsc.edu/speccoll Lick Observatory Records: UA.036.Ser.07 1 Photographs UA.036.Ser.07 Contributing Institution: University of California, Santa Cruz Title: Lick Observatory Records: Photographs Creator: Lick Observatory Identifier/Call Number: UA.036.Ser.07 Physical Description: 101.62 Linear Feet127 boxes Date (inclusive): circa 1870-2002 Language of Material: English . https://n2t.net/ark:/38305/f19c6wg4 Conditions Governing Access Collection is open for research. Conditions Governing Use Property rights for this collection reside with the University of California. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. The publication or use of any work protected by copyright beyond that allowed by fair use for research or educational purposes requires written permission from the copyright owner. Responsibility for obtaining permissions, and for any use rests exclusively with the user. Preferred Citation Lick Observatory Records: Photographs. UA36 Ser.7. Special Collections and Archives, University Library, University of California, Santa Cruz. Alternative Format Available Images from this collection are available through UCSC Library Digital Collections. Historical note These photographs were produced or collected by Lick observatory staff and faculty, as well as UCSC Library personnel. Many of the early photographs of the major instruments and Observatory buildings were taken by Henry E. Matthews, who served as secretary to the Lick Trust during the planning and construction of the Observatory. -

Extra-Terrestrial Meteors

LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS apostolos christou Armagh Observatory and Planetarium College Hill, BT61 9DG Northern Ireland, UK jeremie vaubaillon IMCCE, Observatoire de Paris Paris 75014, France paul withers Astronomy Department, Boston University 725 Commonwealth Avenue Boston MA 02215, USA ricardo hueso Fisica Aplicada I Escuela de Ingenieria de Bilbao Plaza Ingeniero Torres Quevedo 1 48013 Bilbao, Spain rosemary killen NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center Planetary Magnetospheres, Code 695 Greenbelt MD 20771, USA arXiv:2010.14647v1 [astro-ph.EP] 27 Oct 2020 1 1 Extra-Terrestrial Meteors 1.1 Introduction cometary orbits, all-but-invisible except where the particles are packed densely enough to be detectable, typically near The beginning of the space age 60 years ago brought about the comet itself (Sykes and Walker, 1992; Reach and Sykes, a new era of discovery for the science of astronomy. Instru- 2000; Gehrz et al., 2006). Extending meteor observations ments could now be placed above the atmosphere, allowing to other planetary bodies allows us to map out these access to new regions of the electromagnetic spectrum and streams and investigate the nature of comets whose mete- unprecedented angular and spatial resolution. But the im- oroid streams do not intersect the Earth. Observations of pact of spaceflight was nowhere as important as in planetary showers corresponding to the same stream at two or more and space science, where it now became possible – and this planets will allow to study a stream’s cross-section. In ad- is still the case, uniquely among astronomical disciplines – dition, the models used to extract meteoroid parameters to physically touch, sniff and directly sample the bodies and from the meteor data are fine-tuned, to a certain degree, for particles of the solar system. -

Educator's Resource Guide

EDUCATOR’S RESOURCE GUIDE TAKE YOUr students for a walk on the moon. Table of Contents Letter to Educators . .3 Education and The IMAX Experience® . .4 Educator’s Guide to Student Activities . .5 Additional Extension Activities . .9 Student Activities Moon Myths vs. Realities . .10 Phases of the Moon . .11 Craters and Canyons . .12 Moon Mass . .13 Working for NASA . .14 Living in Space Q&A . .16 Moonology: The Geology of the Moon (Rocks) . .17 Moonology: The Geology of the Moon (Soil) . .18 Moon Map . .19 The Future of Lunar Exploration . .20 Apollo Missions Quick-Facts Reference Sheet . .21 Moon and Apollo Mission Trivia . .22 Space Glossary and Resources . .23 Dear Educator, Thank you for choosing to enrich your students’ learning experiences by supplementing your science, math, ® history and language arts curriculums with an IMAX film. Since inception, The IMAX Corporation has shown its commitment to education by producing learning-based films and providing complementary resources for teachers, such as this Educator’s Resource Guide. For many, the dream of flying to the Moon begins at a young age, and continues far into adulthood. Although space travel is not possible for most people, IMAX provides viewers their own unique opportunity to journey to the Moon through the film, Magnificent Desolation: Walking on the Moon. USING THIS GUIDE This thrilling IMAX film puts the audience right alongside the astronauts of the Apollo space missions and transports them to the Moon to experience the first This Comprehensive Educator’s Resource steps on the lunar surface and the continued adventure throughout the Moon Guide includes an Educator’s Guide to Student missions.