Dorothy Sayer's Lord Peter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lord Peter Wimsey As Wounded Healer in the Novels of Dorothy L

Volume 14 Number 4 Article 3 Summer 7-15-1988 "All Nerves and Nose": Lord Peter Wimsey as Wounded Healer in the Novels of Dorothy L. Sayers Nancy-Lou Patterson Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Patterson, Nancy-Lou (1988) ""All Nerves and Nose": Lord Peter Wimsey as Wounded Healer in the Novels of Dorothy L. Sayers," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 14 : No. 4 , Article 3. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol14/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Finds parallels in the life of Lord Peter Wimsey (as delineated in Sayers’s novels) to the shamanistic journey. In particular, Lord Peter’s war experiences have made him a type of Wounded Healer. -

Genre and Gender in Selected Works by Detection Club Writers Dorothy L. Sayers and Agatha Christie

SEVENTY YEARS OF SWEARING UPON ERIC THE SKULL: GENRE AND GENDER IN SELECTED WORKS BY DETECTION CLUB WRITERS DOROTHY L. SAYERS AND AGATHA CHRISTIE A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Monica L. Lott May 2013 Dissertation written by Monica L. Lott B.A., The University of Akron, 2003 B.S., The University of Akron, 2003 M.A., The University of Akron, 2005 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2013 Approved by Tammy Clewell Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Vera Camden Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Robert Trogdon Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Maryann DeJulio Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Clare Stacey Member, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Accepted by Robert Trogdon Chair, English Department Raymond A. Craig Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements.................................................................................... iv Introduction..................................................................................................1 Codification of the Genre.................................................................2 The Gendered Detective in Sayers and Christie ..............................9 Chapter Synopsis............................................................................11 Dorothy L. Sayers, the Great War, and Shell-shock..................................20 Sayers and World War Two in Britain ..........................................24 Shell-shock and Treatment -

Wodehouse and the Psychology of the Individual by Tim Andrew

P lum L in es The quarterly journal of The Wodehouse Society Volume 24 Number 1 Spring 2003 Wodehouse and the Psychology of the Individual by Tim Andrew MUST begin with a disclaimer. Notwithstanding the But you can look at his correspondence if you like. For I title of this article* I am very far from being qualified example this, written to Denis Mackail in 1953: as a psychologist, except through the compulsory atten dance at the University of Life that goes with being a I find in this evening of my life that my principal school principal. I did, I must confess, pretend to study pleasure is in writing stinkers to people who attack me something called “The Psychology of Education” some in the press. I sent Nancy Spain of the Daily Express a 35 years ago, but— in sharp contrast to the formal regu beauty. No answer, so I suppose it killed her. But what lations— most of us on the course regarded it as an fun it is giving up trying to conciliate these lice. It sud optional part of the programme. When the dreaded day denly struck me that they couldn’t possibly do me any of the end-of-year examination loomed, our kindly harm, so now I am roaring like a lion. One yip out of tutor advised us that if we didn’t feel we knew the text any of the bastards and they get a beautifully phrased book answer to any of the questions, we should put our page of vitriol which will haunt them for the rest of own ideas down. -

Dorothy L. Sayers' Bloomsbury Years in Their "Spatial and Temporal Content"

Volume 19 Number 3 Article 2 Summer 7-15-1993 "A Bloomsbury Blue-Stocking": Dorothy L. Sayers' Bloomsbury Years in Their "Spatial and Temporal Content" Nancy-Lou Patterson Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Patterson, Nancy-Lou (1993) ""A Bloomsbury Blue-Stocking": Dorothy L. Sayers' Bloomsbury Years in Their "Spatial and Temporal Content"," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 19 : No. 3 , Article 2. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol19/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Contends that Sayers’s “Bloomsbury years formed a significant source for and influence upon her detective fiction.” Additional Keywords Sayers, Dorothy L.—Biography; Sayers, Dorothy L.—Detective novels—Sources This article is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. -

Contrasting Perspectives in Dorothy Sayers and P

PAPER 4B1 – LAURA KASSON FISS PROCEEDINGS OF ARMISTICE & AFTERMATH: A MICHIGAN TECH SYMPOSIUM ON WWI • SEPT. 28-29 2018 Recalling the Trenches from the Club Window: Contrasting Perspectives in Dorothy Sayers and P. G. Wodehouse Laura Kasson Fiss Michigan Technological University British cultural historians often cite World War I as a pivot point in the advent of modernity and Modernism. Despite pre-war works of Modernism (and Virginia Woolf’s famous tongue-in-cheek statement that “On or about December 1910 human character changed”), World War I is a clear landmark that seems self-evidently an event after which Nothing Would Ever Be The Same. In fact, many works on the Victorian period use 1914 as a bookend when defining the period by broad-reaching political events rather than a change in monarch. (You may have noted that this makes the period longer—Victorianists like to colonize things.) The other end of this period is often the 1832 Reform Act, which began an extension of the franchise to middle-class men. In fact, universal male franchise only came to Britain at the close of the war in 1918, with the same Representation of the People Act that began enfranchising women. While it is undeniable that the First World War had a resounding impact on Britain, its effects, particularly on the literary scene, can be overstated. The Victorians did not just go away in 1914. Particularly in middlebrow culture, much stayed the same—which itself constitutes a response to the war. Take, for example, humorist Jerome K. Jerome, whose 1889 hit Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog) has never been out of print. -

Tolkien, Sayers, Sex and Gender

Volume 21 Number 2 Article 53 Winter 10-15-1996 Tolkien, Sayers, Sex and Gender David Doughan Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Doughan, David (1996) "Tolkien, Sayers, Sex and Gender," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 21 : No. 2 , Article 53. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol21/iss2/53 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Tolkien’s expressed “loathing” for Dorothy Sayers and her novels Gaudy Night and Busman’s Honeymoon is remarkable considering that Sayers is generally considered to belong to the same milieu as the Inklings. Possible reasons for this are the contrast between the orthodox Catholic Tolkien’s view of male sexuality as inherently sinful, requiring “great mortification”, and Sayers’s frankly hedonistic approach. -

Summer Reading

10th Grade Summer Reading Reading is to the mind what exercise is to the body. —Joseph Addison Incoming 10th Graders should read the following book and complete the summer reading assignment. This will prepare them for class activities at the beginning of the school year. King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table by Roger Lancelyn Green Read and Annotate: Annotating is a tool of active reading which helps you understand and ask questions of a text. Underline key information, write notes about thoughts that occur to you in the margins, ask questions, and seek out answers. Use a pencil to have a conversation with the novel as you write. Write a 4-5 paragraph essay: In ninth grade, you studied the ancient world in history and read its tragedies and epics in literature. In tenth grade, we will spend time looking into the medieval world which arose in Western Europe after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Many have argued that the medieval world was a synthesis of the Roman and Christian worlds, along with the cultures of the non-Roman tribes such as the Germanic people. For your topic, choose one of the following questions: 1. Heroism: How does the heroic ideal embodied by King Arthur and his knights compare to the heroic ideal of the ancient world? How is it similar to and in what ways is it different from Achilles or Aeneas? 2. Tragedy: The story of King Arthur is both an epic and a tragedy. How do the causes of the final tragedy (the fall of Logres) compare to the causes of tragedy in the ancient Greek plays you have read? Does the view of human nature and actions change between the ancient tragedies and the story of Arthur? Does this tragedy show a new set of influences? 3. -

Speaking Through Grey Area: the Inter

DEDICATION To my mother and my teachers who brought me up in a world of books so that, as in the case of C.S. Lewis, “You can never get a cup of tea large enough or a book big enough to suit me.” SPEAKING THROUGH GREY AREA: THE INTER WORLD WAR WRITINGS OF T.S. ELIOT AND DOROTHY L. SAYERS BY Hannah a.m. Oliver ABSTRACT The goal of this project is to investigate the relationship of 1930’s British modernism and the popular return to classical western traditions. The project of modernism had many variants depending on the practitioner and a broader reach than the avant-garde realm we have placed it in to allow post-modernism to grow in linear success from modernism. During its time of composition, modernist work was being created in reaction to a period of radical uncertainty. The goal of this essay is not refutation of high modernism, or to idealize the dreaming spires of Oxford, but to bring the conversation between the two as it existed between them at the time. By examining key works of T.S. Eliot and Dorothy L. Sayers we can begin to see where these classical ideals occur and begin building an argument as to why in this era of turmoil perceived by scholars as defeatist, projects of hope and cyclic history flourished. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My eternal gratitude is owed to Mandy Berry, who listened to my enthusiastic rambling and guided it kicking and screaming into an actual argument. Thank you for accompanying me as I built my theoretical house and then discovered what was living inside. -

Whose Body?: BBC Radio 4 Full-Cast Dramatisation PDF Book

WHOSE BODY?: BBC RADIO 4 FULL-CAST DRAMATISATION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dorothy L. Sayers | 2 pages | 12 Oct 2010 | BBC Audio, A Division Of Random House | 9780563529095 | English | London, United Kingdom Whose Body?: BBC Radio 4 Full-cast Dramatisation PDF Book Home Episodes. Stephen Thorne Narrator ,. BBC Programmes. Refresh and try again. It's an interesting enough mystery -- and there was enough of a gap between me reading the book and hearing the radioplay that meant I was puzzling over the exact way Peter would figure things out, which kept me even more entertained. Ian Carmichael Narrator ,. Debonair sleuth Lord Peter Wimsey investigates. I read the book itself a while ago, but this is the BBC radioplay. Paul Lazenby rated it it was ok Apr 27, Community Reviews. In the sharp-witted spinster sleuth Miss Marple made her first appearance in Murder at the Vicarage. Shelley rated it it was amazing Apr 05, Dec 02, The Book Loving Monkey rated it it was amazing Shelves: audiobooks , crime-thriller , the-best. First, we found some gaping holes in Sayers' plots. The Five Red Herrings. However, Sayers herself considered her translation of Dante's Divina Commedia to be her best work. Dorothy Sayer's style is unmistakable. From December She is also known for her plays and essays. Read more Classy and sharp-witted, aristocratic amateur sleuth Lord Peter Bredon Wimsey was born in and educated at Eton and Oxford, before serving in the military during the First World War. Whose Body? Add links. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Sat 11 Nov Ian Carmichael had just played the part on television and they wanted him to reprise the character on radio. -

WHOSE BODY?, the First Lord Peter Wimsey Novel, Published in 1923

As My Wimsey Takes Me, Episode 1 transcript [THEME MUSIC: jaunty Bach-esque piano notes played in counterpoint gradually fading in] CHARIS: Hello, and thank you for joining us for the first episode of As My Wimsey Takes Me. I'm Charis Ellison-- SHARON: --And I'm Sharon Hsu. We're two friends sleuthing our way through the Peter Wimsey mystery novels by Dorothy L. Sayers, and today we're starting our investigation at the very beginning, with WHOSE BODY?, the first Lord Peter Wimsey novel, published in 1923. In the early 1920s, Sayers was struggling with financial uncertainty and, looking for income, asked herself what people were interested in. She decided that everyone liked detectives and the aristocracy. So she wrote about an aristocratic detective. CHARIS: In his first case, Lord Peter encounters two mysteries--one is an unidentified dead body, found in a bathtub that doesn't belong to him, and unseasonably dressed in a pair of pince-nez. The other is a middle-aged financier who appears to have vanished into the night without his clothes, without his glasses, and without a trace. If you haven't read WHOSE BODY? before, don't worry--we won't give away the whodunnit today, but we do hope that, after listening to this episode, you'll read the book and join us again in two weeks for our second episode, where we'll discuss the solution of the case. SHARON: But for now, let's go back to a rainy night 1920s London, and dig into WHOSE BODY? [The sound of heavy rain, and the crunch of footsteps on wet gravel, as if someone is walking past us] CHARIS: So, Sharon, we're coming in on page one of WHOSE BODY? and we're being introduced to a character who's described as having "a long amiable face that looked as if it had generated spontaneously from his tophat, as white maggots breed from Gorgonzola." And this is our introduction to Lord Peter Wimsey. -

Empire and Englishness in the Detective Fiction of Dorothy L. Sayers and PD James

The Imperial Detective: Empire and Englishness in the Detective Fiction of Dorothy L. Sayers and P. D. James. Lynette Gaye Field Bachelor of Arts with First Class Honours in English. Graduate Diploma in English. This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia, School of Social and Cultural Studies, Discipline of English and Cultural Studies. 2011 ii iii TABLE OF CONTENTS STATEMENT OF CONTRIBUTION v ABSTRACT vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ix INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER ONE 27 This England CHAPTER TWO 70 At War CHAPTER THREE 110 Imperial Adventures CHAPTER FOUR 151 At Home AFTERWORD 194 WORKS CITED 199 iv v STATEMENT OF CANDIDATE CONTRIBUTION I declare that the thesis is my own composition with all sources acknowledged and my contribution clearly identified. The thesis has been completed during the course of enrolment in this degree at The University of Western Australia and has not previously been accepted for a degree at this or any other institution. This bibliographical style for this thesis is MLA (Parenthetical). vi vii ABSTRACT Dorothy L. Sayers and P. D. James are writers of classical detective fiction whose work is firmly anchored to a recognisably English culture, yet little attention has been given to this aspect of their work. I seek to redress this. Using Simon Gikandi’s concept of “the incomplete project of colonisation” ( Maps of Englishness 9) I argue that within the works of Sayers and James the British Empire informs and complicates notions of Englishness. Sayers’s Lord Peter Wimsey and James’s Adam Dalgliesh share, with Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, both detecting expertise and the character of the “imperial detective”. -

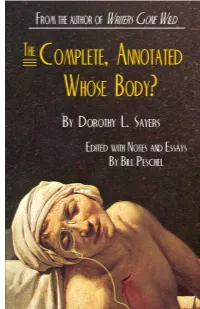

The Complete, Annotated Whose Body?

EXCERPT FROM The Complete, Annotated Whose Body? BY DOROTHY L. SAYERS With Notes, Essays and Chronologies by BILL PESCHEL AUTHOR OF ‘WRITERS GONE WILD’ Peschel Press ~ Hershey, Pa. Available in Trade Paperback, Kindle and other e-reader versions. EXCERPT FROM THE COMPLETE, ANNOTATED WHOSE BODY? Author’s Note This excerpt contains Chapter One, the essays and chronologies of Dorothy L. Sayers‘ life and Lord Peter Wimsey‘s cases. This is what you‘ll see if you buy the trade paperback book (minus this Author‘s Note, of course). The Wimsey Annotations project (at www.planet peschel.com) has been in the works for nearly 15 years and is not yet finished. With the rise in self-publishing, combined with the fact that Sayers‘ first two novels are in the public domain, the time was right for an annotated edition. Researching Sayers‘ life and that of her most famous creation provided fascinating insights into the history of England and its peoples in the 1920s. Sayers was also a well- educated woman, at a time when few women were, and her learning is reflected in Lord Peter‘s aphorisms, witty sayings and direct quotations of everything from classic literature, to Gilbert and Sullivan, to catchphrases of the day. I hope you‘ll find reading ―The Complete, Annotated Whose Body?‖ as enjoyable as I had researching it. Cheers, Bill Peschel THE COMPLETE, ANNOTATED WHOSE BODY? A novel by Dorothy L. Sayers in the public domain in the United States. Notes and Essays Copyright © 2011 Bill Peschel. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America.