Dorothy L. Sayers' Bloomsbury Years in Their "Spatial and Temporal Content"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AWAR of INDIVIDUALS: Bloomsbury Attitudes to the Great

2 Bloomsbury What were the anti-war feelings chiefly expressed outside ‘organised’ protest and not under political or religious banners – those attitudes which form the raison d’être for this study? As the Great War becomes more distant in time, certain actions and individuals become greyer and more obscure whilst others seem to become clearer and imbued with a dash of colour amid the sepia. One thinks particularly of the so-called Bloomsbury Group.1 Any overview of ‘alter- native’ attitudes to the war must consider the responses of Bloomsbury to the shadows of doubt and uncertainty thrown across page and canvas by the con- flict. Despite their notoriety, the reactions of the Bloomsbury individuals are important both in their own right and as a mirror to the similar reactions of obscurer individuals from differing circumstances and backgrounds. In the origins of Bloomsbury – well known as one of the foremost cultural groups of the late Victorian and Edwardian periods – is to be found the moral and aesthetic core for some of the most significant humanistic reactions to the war. The small circle of Cambridge undergraduates whose mutual appreciation of the thoughts and teachings of the academic and philosopher G.E. Moore led them to form lasting friendships, became the kernel of what would become labelled ‘the Bloomsbury Group’. It was, as one academic described, ‘a nucleus from which civilisation has spread outwards’.2 This rippling effect, though tem- porarily dammed by the keenly-felt constrictions of the war, would continue to flow outwards through the twentieth century, inspiring, as is well known, much analysis and interpretation along the way. -

Prime Bloomsbury Freehold Development Opportunity LONDON

BLOOMSBURY LONDON WC2 LONDON WC2 Prime Bloomsbury Freehold Development Opportunity BLOOMSBURY LONDON WC2 INVESTMENT SUMMARY • Prime Bloomsbury location between Shaftesbury Avenue and High Holborn, immediately to the north of Covent Garden. • Attractive period building arranged over lower ground, ground and three upper floors totalling 10,442 sq ft (970.0 sq m) Gross Internal Area. • The property benefits from detailed planning permission, subject to a Section 106 agreement, for change of use and erection of a roof extension to six residential apartments (C3 use) comprising 6,339 sq ft (589.0 sq m) Net Saleable Area and four B1/A1 units totalling 2,745 sq ft (255.0 sq m) Gross Internal Area, providing a total Gross Internal Area of 12,080 sq ft (1,122.2 sq m). • The property will be sold with vacant possession. • The building would be suitable for owner occupiers, developers or investors seeking to undertake an office refurbishment and extension, subject to planning. • Freehold. • The vendor is seeking offers in excess of £8,750,000 (Eight Million, Seven Hundred and Fifty Thousand Pounds) subject to contract and exclusive of VAT, which equates to £838 per sq ft on the existing Gross Internal Area and £724 per sq ft on the consented Gross Internal Area. BLOOMSBURY LONDON WC2 LOCATION The thriving Bloomsbury sub-market sits between Soho to the west, Covent Garden to the south and Fitzrovia to the north. The local area is internationally known for its unrivalled amenities with the restaurants and bars of Soho and theatres and retail provision of Covent Garden a short walk away. -

An Autumn Festival of Art, Knowledge and Imagination Bloomsburyfestival.Org.Uk | Follow Us: @Bloomsburyfest #Bloomsburyfest Introduction Introduction

FREE! An autumn festival of art, knowledge and imagination bloomsburyfestival.org.uk | Follow us: @bloomsburyfest #bloomsburyfest Introduction Introduction As the new Festival Director, I am proud to present the Welcome to the Bloomsbury 2013“ Bloomsbury Festival programme, created and led by the people that live, work, study and play in this small but beautiful corner of London. Bloomsbury Festival shines a light on the self Festival determination of a world-changing community of pioneers existing side- by-side across a few streets. This October the Bloomsbury Festival spills out into the area’s streets, Virginia Woolf once spoke of her sense of freedom upon arriving in Bloomsbury, and I seek shops, museums, libraries and laboratories with a truly eclectic to recapture that same spirit of vitality in every visitor this year. I welcome you into our sanctuary for line-up of unexpected, enlightening and extraordinary things to see and do. Take a the imagination to encounter brilliant minds, relaxation and pleasure, the new and the controversial. musicals masterclass from Sir Tim Rice, hear Turner Prize winner Mark Wallinger in Bloomsbury Festival is an uplifting journey of discovery that aims to inspire, delight, surprise and conversation, listen to Iain Sinclair on Bloomsbury and radicalism, and discover Sir move you. Andrew Motion’s personal literary refuges. As a registered charity we also run a year-round outreach festival for the lonely, taking the best of Bloomsbury right into the living rooms of local isolated people such as those living with dementia. We’ve extended the festival to six days, giving you more time to explore over 200 free Please donate to help continue this vital service and ensure our Festival is kept free for everyone to events across Bloomsbury. -

Middlebrow Feminism in Classic British Detective Fiction

Crime Files Series General Editor: Clive Bloom Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fiction has never been more popular. In novels, short stories, films, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, prim poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fiction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fiction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. Published titles include: Maurizio Ascari A COUNTER-HISTORY OF CRIME FICTION Supernatural, Gothic, Sensational Hans Bertens and Theo D’haen CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CRIME FICTION Anita Biressi CRIME, FEAR AND THE LAW IN TRUE CRIME STORIES Ed Christian (editor) THE POST-COLONIAL DETECTIVE Paul Cobley THE AMERICAN THRILLER Generic Innovation and Social Change in the 1970s Michael Cook NARRATIVES OF ENCLOSURE IN DETECTIVE FICTION The Locked Room Mystery Barry Forshaw DEATH IN A COLD CLIMATE A Guide to Scandinavian Crime Fiction Barry Forshaw BRITISH CRIME FILM Subverting the Social Order Emelyne Godfrey MASCULINITY, CRIME AND SELF-DEFENCE IN VICTORIAN LITERATURE Emelyne Godfrey FEMININITY, CRIME AND SELF-DEFENCE -

A Guide to Camden's Parks and Open Spaces

A Guide to Camden’s Parks and Open Spaces Contents Kilburn, West Hampstead, Swiss Cottage and Primrose Hill 2 Gospel Oak, Hampstead, Highgate and Kentish Town 7 Camden Town, Somers Town, Bloomsbury, Holborn and Fitzrovia 12 Useful contacts and how to get involved 21 Alphabetical list of parks, addresses, features and travel details 27 Index 32 1 Introduction Camden Council manages nearly 70 parks and open spaces. They range from small neighbourhood playgrounds to grand city squares, historic graveyards to allotments. These oases dotted throughout the Borough, complement the bigger and somewhat better known areas that the Council does not manage, such as Hampstead Heath, Primrose Hill and Regents Park. In recent years Camden has spent a good deal of money improving its parks and open spaces. In addition, supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund, over £5 million has been spent on restoring five historic parks (Hampstead Cemetery, Russell Square, St George’s Gardens, St Pancras’ Gardens and Waterlow Park). We have increased the numbers of gardeners and attendants in parks – please let them know what you think of our service, you can identify them by their uniforms. In addition we have Parks Officers on duty every day of the year, backed up by a mobile security patrol. As well as managing public parks, the Parks and Open Spaces Service looks after the Borough’s trees, runs the allotment service and manages a number of large grounds maintenance contracts for other Council departments. We also lead on the Camden Biodiversity Action Plan. We would like you to think of this Guide as a welcoming invitation to Camden’s parks and open spaces. -

Reason and Values in Bloomsbury Fiction

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. REASON AND VALUES m BLOOMS BJRY FICTION A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for t he degree of Master of Arts in English at Massey University. Diane Wendy Wills 1970 "From these primary qualities, Reasonabl eness and a Sense of' Values, may spring a host of secondaries: a tast e for truth and beauty, tol erance, intellectual honesty, fastidiousness, a sense of humour, good manners, curiosity, a dislike of vulgarity, brutality, and over-emphasis, freedom f'rom superstition and prudery, a fearless acceptance of the good things of life, a desire for complete sel.1' expression and for a liberal education, a contempt for utilitarian ism and philistinism, in two ords • sweetness and light. " { Clive Bell. ) iii, PREPACE When I f'irat began looking at the fiction of the Bloomsbury Group I had 11ttle idea of hat my final argum :t would be. Ne, .,, I find my• aelt measuring the values implicit 1n the novel against t h·· l. ,Jl' sfe of Bloom.sbury a.a erated by outside co tators am. by me;i1)Jl·--= •)f Bloan bury itaelf, and ree.ttirm1ng not on13 th indep dence of mind which indiv- idual m ber retained but th ftwlty jU.UJ?J111C11ts ct oh m outsider he.v b guilty• Thi the 1a to be emaustiv cover- age ot Bloomsbul7 ideas in fiction. -

The Late Scholar

The Late Scholar 99871444760866871444760866 TheThe LateLate ScholarScholar (820h).indd(820h).indd i 009/10/20139/10/2013 115:01:235:01:23 By Jill Paton Walsh The Attenbury Emeralds By Jill Paton Walsh and Dorothy L. Sayers A Presumption of Death By Dorothy L. Sayers and Jill Paton Walsh Thrones, Dominations Imogen Quy detective stories by Jill Paton Walsh The Wyndham Case A Piece of Justice Debts of Dishonour The Bad Quarto Detective stories by Dorothy L. Sayers Busman’s Honeymoon Clouds of Witness The Documents in the Case (with Robert Eustace) Five Red Herrings Gaudy Night Hangman’s Holiday Have His Carcase In the Teeth of the Evidence Lord Peter Views the Body Murder Must Advertise The Nine Tailors Striding Folly Strong Poison Unnatural Death The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club Whose Body? 99871444760866871444760866 TheThe LateLate ScholarScholar (820h).indd(820h).indd iiii 009/10/20139/10/2013 115:01:235:01:23 JILL PATON WALSH The Late Scholar Based on the characters of Dorothy L. Sayers 99871444760866871444760866 TheThe LateLate ScholarScholar (820h).indd(820h).indd iiiiii 009/10/20139/10/2013 115:01:235:01:23 First published in 2013 by Hodder & Stoughton An Hachette UK company 1 Copyright © 2013 by Jill Paton Walsh and the Trustees of Anthony Fleming, deceased The right of Jill Paton Walsh to be identifi ed as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

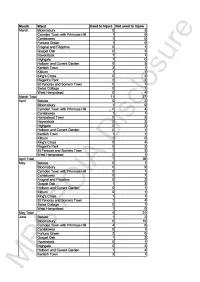

Month Ward Used to Injure Not Used to Injure March Bloomsbury 0 3

Month Ward Used to Injure Not used to injure March Bloomsbury 0 3 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 1 5 Cantelowes 1 0 Fortune Green 1 0 Frognal and Fitz'ohns 0 1 Gospel Oak 0 2 Haverstock 1 1 Highgate 1 0 Holborn and Covent Garden 0 3 Kentish Town 3 1 Kilburn 1 1 King's Cross 0 2 Regent's Park 2 2 St Pancras and Somers Town 0 1 Swiss Cottage 0 1 West Hampstead 0 4 March Total 11 27 April Belsize 0 2 Bloomsbury 1 9 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 0 4 Cantelowes 1 1 Hampstead Town 0 2 Haverstock 2 3 Highgate 0 3 Holborn and Covent Garden 0 1 Kentish Town 1 1 Kilburn 1 0 King's Cross 0 4 Regent's Park 0 2 St Pancras and Somers Town 1 3 West Hampstead 0 1 April Total 7 36 May Belsize 0 1 Bloomsbury 0 9 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 0 1 Cantelowes 0 7 Frognal and Fitzjohns 0 2 Gospel Oak 1 3 Holborn and Covent Garden 0 1 Kilburn 0 1 King's Cross 1 1 St Pancras and Somers Town 1 4 Swiss Cottage 0 1 West Hampstead 1 0 May Total 4 31 June Belsize 1 2 Bloomsbury 0 1 0 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 4 6 Cantelowes 0 1 Fortune Green 2 0 Gospel Oak 1 3 Haverstock 0 1 Highgate 0 2 Holborn and Covent Garden 1 4 Kentish Town 3 1 MPS FOIA Disclosure Kilburn 2 1 King's Cross 1 1 Regent's Park 2 1 St Pancras and Somers Town 1 3 Swiss Cottage 0 2 West Hampstead 0 1 June Total 18 39 July Bloomsbury 0 6 Camden Town with P rimrose Hill 5 1 Cantelowes 1 3 Frognal and Fitz'ohns 0 2 Gospel Oak 2 0 Haverstock 0 1 Highgate 0 4 Holborn and Covent Garden 0 3 Kentish Town 1 0 King's Cross 0 3 Regent's Park 1 2 St Pancras and Somers Town 1 0 Swiss Cottage 1 2 West -

La Dama Que Se Transformó En Zorro

PERIFÉRICA HOJA DE PROMOCIÓN PARA LIBREROS LA OBRA ESTARÁ EN LIBRERÍAS EL 14 DE ABRIL Una mujer que se convierte en un zorro: se trata de un terrible revés de la fortuna, pero de una extraña belleza. Pero el verdadero tema de esta fascinante novela es qué sucederá luego. Y no deberíamos dejarnos engañar por el título, pues hay más de una transformación en ella. David Garnett LA DAMA QUE SE TRANSFORMÓ EN ZORRO COLECCIÓN «LA RGO RECORRIDO » TRADUCCIÓN DE LAURA SALAS Nº DE PÁGINAS: 128 PVP INCLUIDO IVA : 15,75 € ISBN: 978-84-92865-91-8 Silvia, la protagonista de esta novela tan singular como sabiamente alejada de la cursilería, se casa con el terrateniente Richard Tebrick, tras un breve noviazgo, y después de la luna de miel se instalan en la hermosa finca de Rylands, en el condado de Oxfordshire; la casa de los Tebrick es la única mansión en kilómetros a la redonda. Pocos meses después, una tarde, salen a pasear por el bosquecillo de la colina cercana. Aún se comportan como enamorados: van a todas partes juntos y pasean de la mano. Ese día se oye a lo lejos una jauría de perros y, a continuación, la trompa de los cazadores; así que Richard acelera el paso hasta llegar a la linde del bosque, para no perderse el espectáculo. Desde allí dispondrán de una buena panorámica si los zorros aparecen. Su esposa se queda atrás, y él, tomándola de la mano, casi la arrastra. Antes de que alcancen la linde, ella da un violento tirón acompañado de un alarido y, de inmediato, él vuelve la cabeza… Las historias de transformaciones son una manera de dotar de sentido al mundo, de ver las conexiones que el materialismo de nuestra era pasa por alto, y que pertenecen a un universo ordenado no sólo por la razón, sino también por la imaginación, un universo en el que el cambio es la única constante. -

Lord Peter Wimsey As Wounded Healer in the Novels of Dorothy L

Volume 14 Number 4 Article 3 Summer 7-15-1988 "All Nerves and Nose": Lord Peter Wimsey as Wounded Healer in the Novels of Dorothy L. Sayers Nancy-Lou Patterson Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Patterson, Nancy-Lou (1988) ""All Nerves and Nose": Lord Peter Wimsey as Wounded Healer in the Novels of Dorothy L. Sayers," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 14 : No. 4 , Article 3. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol14/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Finds parallels in the life of Lord Peter Wimsey (as delineated in Sayers’s novels) to the shamanistic journey. In particular, Lord Peter’s war experiences have made him a type of Wounded Healer. -

The Bloomsbury Handbook of Global Education and Learning Edited by Douglas Bourn

The Bloomsbury Handbook of Global Education and Learning Edited by Douglas Bourn "A comprehensive introduction to the complexity of Global Education from multiple perspectives, bringing the reader through a journey that highlights the potential but also the deepness of the debates around Global Education." Sara Franch, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, Italy "Due to the plurality of ‘voices’ presented, this book is a must read for scholars and students interested in ensuring that education and active citizenship play a relevant part in promoting global justice." La Salete Coelho, University of Porto, Portugal "The Bloomsbury Handbook of Global Education and Learning is a landmark text in the field of global education. This truly international publication reflects the mainstreaming of global education and learning in solving global challenges for social justice. The preeminent researchers, policy makers and practitioners featured here offer insightful and current analyses with a strong sense of implications for practice.” Philip Bamber, Liverpool Hope University, UK 35% off with this flyer! Hardback | 488 pp | February 2020 | 9781350108738 | £130.00 £84.50 Learning about global issues and themes has become an increasingly recognised element of education in many countries around the world. Terms such as global learning, global citizenship and global education can be seen within national education policies and international initiatives led by the UN, UNESCO, European Commission and OECD. The Bloomsbury Handbook of Global Education and Learning brings together the main elements of the debates, provides analysis of policies, and suggests new directions for research in these areas. Written by internationally renowned scholars from Brazil, Canada, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Pakistan, Poland, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Taiwan, UK and the USA, the handbook offers a much needed resource for academics, researchers, policy-makers and practitioners who need a clear picture of global learning. -

Bloomsbury Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Strategy

Bloomsbury Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Strategy Adopted 18 April 2011 i) CONTENTS PART 1: CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 0 Purpose of the Appraisal ............................................................................................................ 2 Designation................................................................................................................................. 3 2.0 PLANNING POLICY CONTEXT ................................................................................................ 4 3.0 SUMMARY OF SPECIAL INTEREST........................................................................................ 5 Context and Evolution................................................................................................................ 5 Spatial Character and Views ...................................................................................................... 6 Building Typology and Form....................................................................................................... 8 Prevalent and Traditional Building Materials ............................................................................ 10 Characteristic Details................................................................................................................ 10 Landscape and Public Realm..................................................................................................