E Curious Case of Jewish Democracy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dina Feitelson

Dina Feitelson From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia also known as Dina ,(דינה פייטלסון :Dina Feitelson (Hebrew born 1926; died Dina Feitelson-Schur) (דינה פייטלסון-שור :Feitelson-Schur (Hebrew דינה פייטלסון-שור was an Israeli educator and scholar in the field of reading ,(1992 acquisition. Born 1926 Vienna, Austria Died 1992 (aged 65–66) Contents Israel Occupation educator 1 Biography Ethnicity Jewish 2 Awards and honours 3 Publications Citizenship Israeli 4 Further reading Notable awards Israel Prize (1953) 5 See also 6 References 7 External links Biography Feitelson was born in 1926 in Vienna, and emigrated to Mandate Palestine in 1934. She studied in the Herzliya Hebrew Gymnasium in the 32nd class, which graduated in 1944. After graduating she studied philosophy in the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Her studies were interrupted by Israel's War of Independence. During the war she suffered a severe head injury. After graduating she worked as an elementary school teacher and later as an inspector for the Ministry of Education. In parallel she also embarked upon an academic career, initially in the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Then, in 1973, she accepted a post at the University of Haifa, where she became a professor of Education. She continued to work there till her death in 1992. Awards and honours In 1953, Feitelson was awarded the Israel Prize,[1] in its inaugural year, in the field of education for her work on causes of failure in first grade children. She was the first woman to receive this prize, and also the youngest recipient ever (she was aged 27). -

The Land of Israel Symbolizes a Union Between the Most Modern Civilization and a Most Antique Culture. It Is the Place Where

The Land of Israel symbolizes a union between the most modern civilization and a most antique culture. It is the place where intellect and vision, matter and spirit meet. Erich Mendelsohn The Weizmann Institute of Science is one of Research by Institute scientists has led to the develop- the world’s leading multidisciplinary basic research ment and production of Israel’s first ethical (original) drug; institutions in the natural and exact sciences. The the solving of three-dimensional structures of a number of Institute’s five faculties – Mathematics and Computer biological molecules, including one that plays a key role in Science, Physics, Chemistry, Biochemistry and Biology Alzheimer’s disease; inventions in the field of optics that – are home to 2,600 scientists, graduate students, have become the basis of virtual head displays for pilots researchers and administrative staff. and surgeons; the discovery and identification of genes that are involved in various diseases; advanced techniques The Daniel Sieff Research Institute, as the Weizmann for transplanting tissues; and the creation of a nanobiologi- Institute was originally called, was founded in 1934 by cal computer that may, in the future, be able to act directly Israel and Rebecca Sieff of the U.K., in memory of their inside the body to identify disease and eliminate it. son. The driving force behind its establishment was the Institute’s first president, Dr. Chaim Weizmann, a Today, the Institute is a leading force in advancing sci- noted chemist who headed the Zionist movement for ence education in all parts of society. Programs offered years and later became the first president of Israel. -

Israel 2020 Human Rights Report

ISRAEL 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Israel is a multiparty parliamentary democracy. Although it has no constitution, its parliament, the unicameral 120-member Knesset, has enacted a series of “Basic Laws” that enumerate fundamental rights. Certain fundamental laws, orders, and regulations legally depend on the existence of a “state of emergency,” which has been in effect since 1948. Under the Basic Laws, the Knesset has the power to dissolve itself and mandate elections. On March 2, Israel held its third general election within a year, which resulted in a coalition government. On December 23, following the government’s failure to pass a budget, the Knesset dissolved itself, which paved the way for new elections scheduled for March 23, 2021. Under the authority of the prime minister, the Israeli Security Agency combats terrorism and espionage in Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza. The national police, including the border police and the immigration police, are under the authority of the Ministry of Public Security. The Israeli Defense Forces are responsible for external security but also have some domestic security responsibilities and report to the Ministry of Defense. Israeli Security Agency forces operating in the West Bank fall under the Israeli Defense Forces for operations and operational debriefing. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security services. The Israeli military and civilian justice systems have on occasion found members of the security forces to have committed abuses. Significant human -

About the Yom's

- Mourning, Joy and Hope!” and Joy Mourning, - “Not just History; Living Memory Living History; just “Not 5, 4, and 28 and 4, 5, Iyar 27, Nissan April 23, May, 1, 2, and 24 24 and 2, 1, May, 23, April Collective Responses to Recent Jewish History Jewish Recent to Responses Collective Yom Yerushaliem) Yom Yom HaAtzmaut, and HaAtzmaut, Yom HaZikaron, Yom HaShoah, (Yom The Yom’s The All about All Fun Facts The flag of Israel was selected in 1948, only 5 months after the state was established. The flag includes two blue stripes on white background with a blue Shield of David (6 pointed star) in the center. The chosen colors blue & white symbolize trust and honesty. On the afternoon of Jerusalem’s liberation, June 7, 1967, Israeli Defense Minister Moshe Dayan made the following statement from the Western Wall: We have united Jerusalem, the divided capital of Israel. We have returned to the holiest of our holy places, never to part from it again. To our Arab neighbors we extend, also at this hour — and with added emphasis at this hour — our hand in peace. And to our Christian and Muslim fellow citizens, we solemnly promise full religious freedom and rights. We did not come to Jerusalem for the sake of other peoples’ holy places, and not to interfere with the adherents of other faiths, but in order to safeguard its entirety, and to live there together with others, in unity. As long as deep within the heart a Jewish soul stirs, and forward to the ends of the East an eye looks out towards Zion, our hope is not yet lost. -

Prof. Jaacov Katan Awarded the Israel Prize in Agriculture

Phytoparasitica DOI 10.1007/s12600-014-0398-1 Prof. Jaacov Katan awarded the Israel Prize in Agriculture # Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2014 Prof. Katan’s research interests included: Soilborne pathogens causing plant disease; ecology and control; soil solarization for pest control; the fate of pesticides in soil; genetic relatedness among Fusarium fungi; and alternatives to methyl bromide. Accordingly, his re- search projects have included integrated control of soilborne pathogens with emphasis on solarization; alternative means of control to avoid application of methyl bromide; modeling the use of solarization; pes- ticides’ behavior in soil; and development of tomato lines resistant to diseases. In addition to his research, he is an outstanding teacher. He has advised more than 70 M.Sc. and Ph.D. Prof. Jaacov Katan has been awarded the Israel Prize for students, some of whom today play prominent roles Agricultural Research and Environmental Science for in research and teaching in Israel and abroad. For 2014. It will be presented by the President of the State more than 20 years, he was elected annually as an on Israel’s Independence Day. The award committee 'Outstanding Teacher' by the students of the Faculty of cited Prof. Katan for his significant contributions Agriculture. In appreciation of his role as a teacher, in and especially for the important finding and deve- 1994 he was awarded the M. Millikan Prize, for distinc- lopment of soil solarization as an environmentally tion in teaching in The Hebrew University of Jerusalem; safe and friendly method to manage soilborne pests, and in 2003 he was given the Rector’s Prize of The using solar energy. -

Israel (Includes West Bank and Gaza) 2020 International Religious Freedom Report

ISRAEL (INCLUDES WEST BANK AND GAZA) 2020 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The country’s laws and Supreme Court rulings protect the freedoms of conscience, faith, religion, and worship, regardless of an individual’s religious affiliation. The 1992 Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty describes the country as a “Jewish and democratic state.” The 2018 Basic Law: Israel – The Nation State of the Jewish People law determines, according to the government, that “the Land of Israel is the historical homeland of the Jewish people; the State of Israel is the nation state of the Jewish People, in which it realizes its natural, cultural, religious and historical right to self-determination; and exercising the right to national self- determination in the State of Israel is unique to the Jewish People.” In June, authorities charged Zion Cohen for carrying out attacks on May 17 on religious institutions in Petah Tikva, Ashdod, Tel Aviv, and Kfar Saba. According to his indictment, Cohen sought to stop religious institutions from providing services to secular individuals, thereby furthering his goal of separating religion and the state. He was awaiting trial at year’s end. In July, the Haifa District Court upheld the 2019 conviction and sentencing for incitement of Raed Salah, head of the prohibited Islamic Movement, for speaking publicly in favor an attack by the group in 2017 that killed two police officers at the Haram al-Sharif/Temple Mount. In his defense, Salah stated that his views were religious opinions rooted in the Quran and that they did not include a direct call to violence. -

Pressed Minority, in the Diaspora

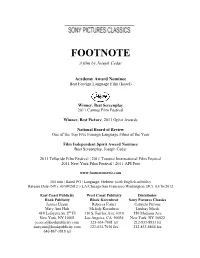

FOOTNOTE A film by Joseph Cedar Academy Award Nominee Best Foreign Language Film (Israel) Winner, Best Screenplay 2011 Cannes Film Festival Winner, Best Picture, 2011 Ophir Awards National Board of Review One of the Top Five Foreign Language Films of the Year Film Independent Spirit Award Nominee Best Screenplay, Joseph Cedar 2011 Telluride Film Festival | 2011 Toronto International Film Festival 2011 New York Film Festival | 2011 AFI Fest www.footnotemovie.com 105 min | Rated PG | Language: Hebrew (with English subtitles) Release Date (NY): 03/09/2012 | (LA/Chicago/San Francisco/Washington, DC): 03/16/2012 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Hook Publicity Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Jessica Uzzan Rebecca Fisher Carmelo Pirrone Mary Ann Hult Melody Korenbrot Lindsay Macik 419 Lafayette St, 2nd Fl 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10003 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 [email protected] 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel [email protected] 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax 646-867-3818 tel SYNOPSIS FOOTNOTE is the tale of a great rivalry between a father and son. Eliezer and Uriel Shkolnik are both eccentric professors, who have dedicated their lives to their work in Talmudic Studies. The father, Eliezer, is a stubborn purist who fears the establishment and has never been recognized for his work. Meanwhile his son, Uriel, is an up-and-coming star in the field, who appears to feed on accolades, endlessly seeking recognition. Then one day, the tables turn. When Eliezer learns that he is to be awarded the Israel Prize, the most valuable honor for scholarship in the country, his vanity and desperate need for validation are exposed. -

Israel “ a New Nation Is Born”

What we would like students to learn Included in this lesson: Each teachable lesson includes everything needed for the lesson. The teacher may need to make copies and/or supply pencils, crayons, scissors, glue, etc… Teacher will: Do some of all of the following: Read information page, copy, cut, provide scissors, paper, glue, etc… An activity to evoke student interest How to present the information included Creative ways to involve students in learning the material An opportunity to make the information meaningful to the individual student 1. Events from Biblical times to the First Zionist Congress; “From generation to generation” 2. Events during the establishment of the State of Israel “ A new nation is born” 3. Theodore Herzl “If you will it..” 4. Eliezer Ben Yehuda, Joseph Trumpeldor, Vladimer Jabotinsky: “Early Heroes of Israel” 5. Chaim Weitzmann, David Ben Gurion, Golda Meir “Profiles in Courage” 6. Rachel, Henrietta Szold, Rav Kook “Those who made a difference” 7. Mickey Marcus, Yigael Yadin, Abba Eban “Biographies of Bravery” 8. Moshe Dayan, Menachem Begin, Yitzchak Rabin “Modern Marvels” 9. Israel Geography Game “Find me on the Map” 10. Israel Heroes Bingo Game 11. Israel travel agency “Pack your bags…destination Israel” Israel: Lesson 1 To become familiar with the timeline events. Included in this lesson: Timeline Teacher will: Make a copy of the timeline for each group of students Provide scissors, string and 40 paperclips for each group How many people can we name in our history? List names on poster or board. Today we are going to see where they fit on our timeline. -

“The Man - Not the Metal”

“The Man - Not The Metal” Address by Chief of Staff Yitzhak Rabin upon receiving the Honorary Doctorate of Philosophy at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Mount Scopus, Jerusalem June 28, 1967 Your Excellency, President of the State; Mr. Prime Minister; President of the Hebrew University; Governors; teachers; ladies and gentlemen. I stand in awe before you, leaders of our generation, here in this venerable and magnificent place, overlooking Israel’s eternal capital and the birthplace of our people’s ancient history. Together with other distinguished people, who are no doubt worthy of this honor, you have chosen to do me great honor by conferring upon me the title of Doctor of Philosophy. Permit me to express to you here what is in my heart: I regard myself at this time as the representative of thousands of commanders and tens of thousands of soldiers who brought the State of Israel its victory in the Six-Day War, as a representative of the entire I.D.F. [Israel Defense Forces]. It may be asked why the university saw fit to grant the title of Honorary Doctor of Philosophy to a soldier in recognition of his martial activities. What is there in common between military activity and the academic world which represents civilization and culture? What is there in common between those whose profession is violence, and spiritual values? I, however, am honored that through me you are expressing such deep appreciation to my comrades-in-arms and to the uniqueness of the Israel Defense Forces, which is essentially an extension of the unique spirit of the entire Jewish people. -

Miriam Peretz – Curriculum Vitae

Miriam Peretz – Curriculum Vitae Miriam Peretz is a devoted educational leader. She is a teacher and educator to her very core. Over the last decade, Miriam has been involved in extensive diplomatic activity to reinforce ties with the Jewish Diaspora and strengthen Israel’s relations with world leaders. Miriam made Aliyah from Morocco and lived in a transit camp in Beer Sheva. She then moved to Sharm El-Sheikh in the Sinai Peninsula and then to Pisgat Ze’ev. Since then, Miriam has dedicated her life to enhancing the Jewish spirit in education and in the community. Miriam Peretz resides in Givat Ze’ev. She is the widow of Eliezer and mother to the late Uriel and Eliraz, as well as to Hadas, Avichai, Elyasaf, and Bat El. Education 1974–1979 B.A. in History of the Jewish People and Hebrew Literature Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Teaching Diploma Ben-Gurion University of the Negev 1989–1991 Executive Training Course The Hebrew University of Jerusalem 1994–1997 M.Ed. in Educational Administration The Hebrew University of Jerusalem 1995–1996 Studies in Advertising, Marketing, and Public Relations College of Management Academic Studies 1997–1998 Graduate of Elka, the Joint’s interdisciplinary program for the development of senior staff at the Ministry of Education 2000–2001 TALI Educational Leadership Course Schechter Institute Formal and Informal Training Executive training, a community activists course at the Hebrew University, a training development course at the Hebrew University, a course on evaluating and monitoring in education at the School for Senior Education Professionals, and multiple administrative and pedagogical training programs over the years. -

Arab-Jewish Relations in Israel: Alienation and Rapprochement

[PEACEW RKS [ ARAB-JEWISH RELATIONS IN ISRAEL ALIENATION AND RAPPROCHEMENT Sammy Smooha ABOUT THE REPO R T This report is a result of a Jennings Randolph Fellow- ship at the U.S. Institute of Peace. The author would like to thank Chantal de Jonge Oudraat, Pierre van den Berge, Andreas Wimmer, and Shibley Telhami for their helpful comments and other assistance in preparing this report. Any errors or factual inaccuracies in the report are solely the responsibility of the author. ABOUT THE AUTHO R Sammy Smooha was a 2009–10 Jennings Randolph Senior Fellow at the U.S. Institute of Peace in Washington, D.C. He is professor of sociology at the University of Haifa and specializes in ethnic relations and in the study of Israeli society in comparative perspective. Widely published and an Israel Prize laureate for sociology in 2008, he was president of the Israeli Sociological Society from 2008 to 2010. Photo: iStock The views expressed in this report are those of the authors alone. They do not necessarily reflect views of the United States Institute of Peace. United States Institute of Peace 1200 17th Street NW, Suite 200 Washington, DC 20036-3011 Phone: 202.457.1700 Fax: 202.429.6063 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.usip.org Peaceworks No. 67. First published 2010. © 2010 by the United States Institute of Peace CONTENTS PEACEWORKS • DECEMBER 2010 • NO. 67 Summary ... 3 Introduction ... 5 Arab-Jewish Relations ... 5 Alienation or Rapprochement? ... 6 The Lost Decade ... 9 The Index of Relations ... 13 Public Opinion ... 15 Drivers of Coexistence ... 24 Policy Implications .. -

Israel's Basic Questions Revisited

PAGE 2 p Spring 2015 PRESIDENT'S MEMO Zionism: The Unfinished Task PAGE 15 ELECTION SEASON, AGAIN Israel’s electoral structure helps explain frequent returns ISRAEL to the voting booth PAGE 21 INSTITUTE ECHOES OF REVISIONISM MAGAZINE The history and legacy of Menachem Begin IN THIS ISSUE: Israel’s Basic Questions Revisited Experts discuss Zionism and Jewish statehood KOLDIRECTOR'SSPOTLIGHT: HAMACHON LETTER ACADEMIA It is a great pleasure to be able to offer this second issue of Israel Institute Magazine. We are very excited to be able to share with you insights from the work of the Institute over the last several months. In this issue of the magazine, you will be able to read about our ongo- ing discussion on Zionism, a topic that has been the focus of many of the Institute’s recent activities and the research of many of its affiliated scholars. The subject of our annual conference, held this past fall, was the continuing relevance of Zionism as an organizing concept. It is no secret that Israel is undergoing a period of signif- icant change. The founding generation is dwindling and the second generation of state lead- ers – those who were children when the state was created but who turned Zionism from a revolution into an established, enduring and functioning state – are themselves passing on the reins to a generation that was born after the state was created. The Zionism that powered the transformation of the Jewish people from a diaspora nation into a sovereign nation-state must, naturally, evolve. In this issue of Israel Insti- tute Magazine, we report on our annual conference and the ideas that it raised in relation to the meaning of modern Zionism for today’s Israelis and for diaspora Jews.