(COVID-19) Outbreak: an Experience from Daegu, Korea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Differentiate Red Eye Disorders

Introduction DIFFERENTIATE RED EYE DISORDERS • Needs immediate treatment • Needs treatment within a few days • Does not require treatment Introduction SUBJECTIVE EYE COMPLAINTS • Decreased vision • Pain • Redness Characterize the complaint through history and exam. Introduction TYPES OF RED EYE DISORDERS • Mechanical trauma • Chemical trauma • Inflammation/infection Introduction ETIOLOGIES OF RED EYE 1. Chemical injury 2. Angle-closure glaucoma 3. Ocular foreign body 4. Corneal abrasion 5. Uveitis 6. Conjunctivitis 7. Ocular surface disease 8. Subconjunctival hemorrhage Evaluation RED EYE: POSSIBLE CAUSES • Trauma • Chemicals • Infection • Allergy • Systemic conditions Evaluation RED EYE: CAUSE AND EFFECT Symptom Cause Itching Allergy Burning Lid disorders, dry eye Foreign body sensation Foreign body, corneal abrasion Localized lid tenderness Hordeolum, chalazion Evaluation RED EYE: CAUSE AND EFFECT (Continued) Symptom Cause Deep, intense pain Corneal abrasions, scleritis, iritis, acute glaucoma, sinusitis, etc. Photophobia Corneal abrasions, iritis, acute glaucoma Halo vision Corneal edema (acute glaucoma, uveitis) Evaluation Equipment needed to evaluate red eye Evaluation Refer red eye with vision loss to ophthalmologist for evaluation Evaluation RED EYE DISORDERS: AN ANATOMIC APPROACH • Face • Adnexa – Orbital area – Lids – Ocular movements • Globe – Conjunctiva, sclera – Anterior chamber (using slit lamp if possible) – Intraocular pressure Disorders of the Ocular Adnexa Disorders of the Ocular Adnexa Hordeolum Disorders of the Ocular -

Chronic Conjunctivitis

9/8/2017 Allergan Pharmaceuticals Speaker’s Bureau Bio-Tissue BioDLogics, LLC Katena/IOP Seed Biotech COA Monterey Symposium 2017 Johnson and Johnson Vision Care, Inc. Shire Pharmaceuticals Nicholas Colatrella, OD, FAAO, Dipl AAO, ABO, ABCMO Jeffrey R. Varanelli, OD, FAAO, Dipl ABO, ABCMO Text NICHOLASCOLA090 to 22333 to join Live Text Poll Nicholas Colatrella, OD, FAAO, Dipl AAO, Jeffrey Varanelli, OD, FAAO, Dipl ABO, ABO, ABCMO ABCMO Text NICHOLASCOLA090 to 22333 once to join Then text A, B, C, D, E or write in your answer Live Immediate Accurate Chronic conjunctivitis is one of the most frustrating reasons that patients present to the office (1) Time course Often times patients will seek multiple providers searching for a solution The chronicity of their symptoms is extremely frustrating to the (2) Morphology patient and treating physician alike Some conditions can seriously affect vision and create ocular morbidity (3) Localization of disease process Many of these diseases do not respond to commonly used topical antibiotics, topical steroids, artificial tears, and other treatments for external ocular disease (4) Type of discharge or exudate Our hope during this one-hour lecture is to present a process to help aid in the diagnosis of chronic conjunctivitis help you determine the most likely etiology 1 9/8/2017 Three weeks is the dividing point as it is the upper limit for cases of viral infection and most bacterial infections to resolve without treatment. Acute Conjunctivitis Conjunctivitis that has been present for less than 3 weeks -

Quality of Vision in Eyes with Epiphora Undergoing Lacrimal Passage Intubation

Quality of Vision in Eyes With Epiphora Undergoing Lacrimal Passage Intubation SHIZUKA KOH, YASUSHI INOUE, SHINTARO OCHI, YOSHIHIRO TAKAI, NAOYUKI MAEDA, AND KOHJI NISHIDA PURPOSE: To investigate visual function and optical PIPHORA, THE MAIN COMPLAINT OF PATIENTS WITH quality in eyes with epiphora undergoing lacrimal passage lacrimal passage obstruction, causes blurred vision, intubation. discomfort, and skin eczema, and may even cause so- E DESIGN: Prospective case series. cial embarrassment. Several studies have assessed the qual- METHODS: Thirty-four eyes of 30 patients with ity of life (QoL) or vision-related QoL of patients suffering lacrimal passage obstruction were enrolled. Before and from lacrimal disorders and the impact of surgical treat- 1 month after lacrimal passage intubation, functional vi- ments on QoL, using a variety of symptom-based question- sual acuity (FVA), higher-order aberrations (HOAs), naires.1–8 According to these studies, epiphora negatively lower tear meniscus, and tear clearance were assessed. affects QoL physically and socially; however, surgical An FVA measurement system was used to examine treatment can improve QoL. Increased tear meniscus changes in continuous visual acuity (VA) over time, owing to inadequate drainage contributes to blurry and visual function parameters such as FVA, visual main- vision.9 However, quality of vision (QoV) has not been tenance ratio, and blink frequency were obtained. fully quantified in eyes with epiphora, and the effects of Sequential ocular HOAs were measured for 10 seconds lacrimal surgery on such eyes are unknown. after the blink using a wavefront sensor. Aberration Dry eye, a clinically significant multifactorial disorder of data were analyzed in the central 4 mm for coma-like, the ocular surface and tear film, may cause visual distur- spherical-like, and total HOAs. -

Eye Infections

CLINICAL Approach Taking a Look at Common Eye Infections John T. Huang, MD, FRCSC and Peter T. Huang, MD, FRCSC he acutely red eye is often seen first by the primary-care physician. The exact Tcause may be difficult to determine and may cause some concern that a serious ocular condition has been missed. Thorough history and clinical examination will help delineate the final diagnosis. When there are doubts, prompt referral to an oph- thalmologist can prevent serious consequences. Often, the most likely diagnosis of an acutely red eye is acute conjunctivitis. In the first day, an acute bacterial infection may be hard to differentiate from viral, chlamydial and noninfectious conjunctivitis and from episcleritis or scleritis. Below is a review of the most commonly seen forms of eye infections and treat- ments. Failure to improve after three to five days should lead to a re-evaluation of the patient and appropriate referral where necessary. CHRONIC BLEPHARITIS Clinical: Gritty burning sensation, mattering, lid margin swelling and/or scaly, flaky debris, mild hyperemia of conjunctiva; may have acne rosacea or hyperkeratotic dermatitis (Figure 1). Anterior: Staphylococcus aureus (follicles, accessory glands); posterior (meibomian glands). Treatment: • Lid scrubs (baby shampoo, lid-care towellettes, warm compresses). Figure 1. Chronic blepharitis. There may be localized sensitivity to the shampoo or the components of the solution in the towellettes (e.g., benzyl alcohol). • Hygiene is important for the treatment and management of chronic blepharitis. Topical antibiotic-corticosteroid combinations (e.g., tobramycin drops, tobramycin/dexamethasone or sulfacetamide sodium-prednisolone acetate). Usage of these medications is effective in providing symptomatic relief, as the inflammatory component of the problem is more effectively dealt with. -

Diagnosis and Management of Common Eye Problems

Diagnosis and Management of Common Eye Problems Review of Ocular Anatomy Picture taken from Basic Ophthalmology for Medical Students and Primary Care Residents published by the American Academy of Ophthalmology Diagnosis and Management of Common Eye Problems Fernando Vega, MD Lacrimal system and eye musculature Eyelid anatomy Picture taken from Basic Ophthalmology for Medical Students and Primary Care Residents published by the American Academy of Ophthalmology n Red Eye Disorders: An Anatomical Approach n Lids n Orbit n Lacrimal System n Conjunctivitis n Cornea n Anterior Chamber Fernando Vega, MD 1 Diagnosis and Management of Common Eye Problems Red Eye Disorders: What is not in the scope of Red Eye Possible Causes of a Red Eye n Loss of Vision n Trauma n Vitreous Floaters n Chemicals n Vitreous detatchment n Infection n Retinal detachment n Allergy n Chronic Irritation n Systemic Infections Symptoms can help determine the Symptoms Continued diagnosis Symptom Cause Symptom Cause Itching allergy Deep, intense pain Corneal abrasions, scleritis Scratchiness/ burning lid, conjunctival, corneal Iritis, acute glaucoma, sinusitis disorders, including Photophobia Corneal abrasions, iritis, acute foreign body, trichiasis, glaucoma dry eye Halo Vision corneal edema (acute glaucoma, Localized lid tenderness Hordeolum, Chalazion contact lens overwear) Diagnostic steps to evaluate the patient with Diagnostic steps continued the red eye n Check visual acuity n Estimate depth of anterior chamber n Inspect pattern of redness n Look for irregularities in pupil size or n Detect presence or absence of conjunctival reaction discharge: purulent vs serous n Look for proptosis (protrusion of the globe), n Inspect cornea for opacities or irregularities lid malfunction or limitations of eye n Stain cornea with fluorescein movement Fernando Vega, MD 2 Diagnosis and Management of Common Eye Problems How to interpret findings n Decreased visual acuity suggests a serious ocular disease. -

Eye Lid Infections Dr Simon Barnard

Eye Lid Infections Dr Simon Barnard Eye Lid Infections Dr Simon Barnard PhD BSc FCOptom FAAO DCLP DipClinOptom Director of Ocular Medicine Institute of Optometry, London Visiting Lecturer Department of Optometry & Visual Science City University, London Ocular Therapeutics – what we can treat now Dr Simon Barnard Eye lid infections Acute ulcerative/staphylococcal blepharitis Acute staphylococcal blepharitis presents with brittle crusty, yellow scales along lid margin. The patient may report that the lid margins are tender and red. A secondary keratoconjunctivitis with superficial punctuate keratitis (SPK) with sterile “island” infiltrates at the 2- 4- 8- & 10 o‟clock positions may be present as an inflammatory reaction to alpha exotoxins released by the bacteria. Treatment of acute ulcerative blepharitis Lid hygiene is very important and the first treatment to prescribe. Lid hygiene consists of scrubs and compresses. Lid scrubs should be carried out twice daily for a week and thereafter once daily using cotton wool buds dipped into a dilute solution of Baby Shampoo or using proprietary cleaning pads such as Lid Care (CIBA) or Supranettes (Alcon) In conjunction with the lid scrubs, very warm compresses should be applied by the patient four times per day for the first week tapering to once daily after resolution. Broad spectrum antibiotics (e.g., Brolene, Polyfax (bacitracin + polymyxin B) may be „prescribed‟. For SPK/infiltrates consider a steroid/antibiotic „combo‟ (e.g., framycetin + gramicidin + dexamethasone). The GP will usually co-operate in prescribing medications not currently on our list. It is advisable to follow up the patient in one to two weeks. If not resolving then consider adding oral antibiotic (e.g., oxytetracycline). -

Eyelid and Orbital Emergencies Charles D

Eyelid and Orbital Emergencies Charles D. Rice M.D. Financial Disclosure Speaker, Charles Rice, M.D. has a financial interest/agreement or affiliation with Lansing Ophthalmology, where he is a shareholder and employed as a oculoplastic surgeon. Eyelid Emergencies/Urgencies • Chalazion with localized cellulitis • Preseptal Cellulitis • Contact Dermatitis • Canaliculitis • Dacryocystitis • Eyelid/Conjunctival Foreign Body Orbital Emergencies • Orbital Cellulitis • Orbital Inflammation • Thyroid Orbital Inflammation • Orbital Hemorrhage • Orbital and Eyelid Trauma Management • History • Exam Visual Acuity Pupillary Reaction Eyelid and Lacrimal Exam Globe position and Extraocular Motility Management • Diagnosis Differential Testing • Treatment Medications Surgery Referral Chalazion Chalazion with Localized Cellulitis • May be diffuse cellulitis • Usually painful • Consider dacryocystitis, canaliculitis, orbital cellulitis • Localized swelling and redness later Chalazion with Localized Cellulitis Treatment • Oral antibiotic Cephalosporin, Cipro, Bactrim • Topical antibiotic/steroid • Hot compresses • Incision and drainage later • 45 yo female • 1 month history of progressive redness and itching of eyelid area • Started on tobramycin and erythromycin topical • Benadryl • Lid scrubs • Problem continued to worsen Contact Dermatitis • Usually acute process • Redness, edema, flaking of skin • Unilateral or bilateral • Ocular exam usually normal • Exposure to chemicals or allergens • Pesticides, make-up, nail polish, plant materials • Consider bacterial -

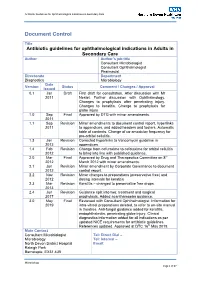

Antibiotic Guidelines for Ophthalmology V1.8 290413 Issue Date Review Date Review Cycle May 2019 May 2022 Three Years Consulted with the Following Stakeholders

Antibiotic Guidelines for Ophthalmological Indications in Secondary Care Document Control Title Antibiotic guidelines for ophthalmological indications in Adults in Secondary Care Author Author’s job title Consultant Microbiologist Consultant Ophthalmologist Pharmacist Directorate Department Diagnostics Microbiology Date Version Status Comment / Changes / Approval Issued 0.1 Jan Draft First draft for consultation. After discussion with Mr 2011 Nestel. Further discussion with Ophthalmology. Changes to prophylaxis after penetrating injury. Changes to keratitis. Change to prophylaxis for globe injury 1.0 Sep Final Approved by DTG with minor amendments. 2011 1.1 Sep Revision Minor amendments to document control report, hyperlinks 2011 to appendices, and added headers and footers. Automatic table of contents. Change of co-amoxiclav frequency for pre-orbital cellulitis. 1.3 Jan Revision Corrected hyperlinks to Vancomycin guideline in 2012 appendices. 1.4 Feb Revision Change from cefuroxime to cefotaxime for orbital cellulitis 2012 to bring into line with published guidance. 2.0 Mar Final Approved by Drug and Therapeutics Committee on 8th 2012 March 2012 with minor amendments. 2.1 Jun Revision Minor amendment by Corporate Governance to document 2012 control report. 2.2 Nov Revision Minor changes to preparations (preservative free) and 2012 dosing intervals for keratitis 2.3 Mar Revision Keratitis – changed to preservative free drops. 2013 2.4 Jun Revision Guidance split into two: treatment and surgical 2017 prophylaxis. Added acanthamoeba guidance. 3.0 May Final Reviewed with Consultant Ophthalmologist. Information for 2019 intra-vitreal preparations deleted, to refer to on-site manual in theatres. Anti-fungal guidance added for keratitis, endophthalmitis, penetrating globe injury. Clinical diagnostics information added for all indications as per updated NICE requirements for antibiotic guidelines. -

Ophthalmic Manifestations of Acute Leukaemias T Sharma Et Al 664

Eye (2004) 18, 663–672 & 2004 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-222X/04 $30.00 www.nature.com/eye 1 1 2 1 Ophthalmic T Sharma , J Grewal , S Gupta and PI Murray REVIEW manifestations of acute leukaemias: the ophthalmologist’s role Abstract neoplastic cells. Ophthalmic involvement can be classified into two major categories: (1) primary With evolving diagnostic and therapeutic or direct leukaemic infiltration, (2) secondary or advances, the survival of patients with acute indirect involvement. The direct leukaemic leukaemia has considerably improved. This infiltration can show three patterns: anterior has led to an increase in the variability of segment uveal infiltration, orbital infiltration, ocular presentations in the form of side effects and neuro-ophthalmic signs of central nervous of the treatment and the ways leukaemic system leukaemia that include optic nerve relapses are being first identified as an ocular infiltration, cranial nerve palsies, and presentation. Leukaemia may involve many papilloedema. The secondary changes are the ocular tissues either by direct infiltration, result of haematological abnormalities of haemorrhage, ischaemia, or toxicity due to leukaemia such as anaemia, thrombocytopenia, various chemotherapeutic agents. Ocular hyperviscosity, and immunosuppression. These involvement may also be seen in graft-versus- can manifest as retinal or vitreous haemorrhage, host reaction in patients undergoing infections, and as vascular occlusions. In some allogeneic bone marrow transplantation, or cases the ocular involvement may be simply as increased susceptibility to infections asymptomatic. In one prospective study, there as a result of immunosuppression that these was a high prevalence of asymptomatic ocular 1 patients undergo. This can range from simple Birmingham and Midland lesions in childhood acute leukaemia.1 In the era bacterial conjunctivitis to an endophthalmitis. -

Twelfth Edition

SUPPLEMENT TO April 15, 2010 www.revoptom.com Twelfth Edition Joseph W. Sowka, O.D., FAAO, Dipl. Andrew S. Gurwood, O.D., FAAO, Dipl. Alan G. Kabat, O.D., FAAO 001_ro0410_hndbkv7.indd 1 4/5/10 8:47 AM TABLE OF CONTENTS Eyelids & Adnexa Conjunctiva & Sclera Cornea Uvea & Glaucoma Vitreous & Retina Neuro-Ophthalmic Disease Oculosystemic Disease EYELIDS & ADNEXA VITREOUS & RETINA Floppy Eyelid Syndrome ...................................... 6 Macular Hole .................................................... 35 Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus ................................ 7 Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion .............................37 Canaliculitis ........................................................ 9 Central Retinal Vein Occlusion............................. 40 Dacryocystitis .................................................... 11 Acquired Retinoschisis ........................................ 43 CONJUNCTIVA & SCLERA NEURO-OPHTHALMIC DISEASE Acute Allergic Conjunctivitis ................................ 13 Melanocytoma of the Optic Disc ..........................45 Pterygium .......................................................... 16 Demyelinating Optic Neuropathy (Optic Neuritis, Subconjunctival Hemmorrhage ............................ 18 Retrobulbar Optic Neuritis) ................................. 47 Traumatic Optic Neuropathy ...............................50 CORNEA Pseudotumor Cerebri .......................................... 52 Corneal Abrasion and Recurrent Corneal Erosion ..20 Craniopharyngioma .......................................... -

Answer to Ophthaproblem Continued from Page 55 4. Dacryocystitis

Ophthaproblem Answer to Ophthaproblem continued from page 55 conducted. It is essential to note any decrease in extra- ocular movement and any signs of proptosis, as these 4. Dacryocystitis are suggestive of orbital cellulitis, a serious ocular com- Dacryocystitis is an inflammation and infection of plication. If discharge is released upon digital palpation the lacrimal sac, usually caused by nasolacrimal duct of the punctum, it should be swabbed and sent for Gram obstruction.1-3 It can be classified as acute, subacute, or stain and blood agar culture (as well as chocolate agar chronic, and can be localized to the sac, extend to the in the pediatric population).1 There is agreement in the pericystitis, or progress further to cause orbital cellu- literature that patients should immediately be started on litis.3 Congenital lacrimal duct obstruction can carry a systemic antibiotics, with further adjustments based on higher chance of secondary infection, leading to dacryo- clinical response and culture or sensitivity results.1,2 The cystocele formation. Most congenital dacryocystoceles severity of the patient’s symptoms, as well as patient will require surgical intervention.4 age, dictates the choice of treatment. In dacryocystitis, patients often present with pain, The following describes the possible therapies for a tearing, redness, and swelling over the lacrimal sac (ie, bacterial or infectious (but currently unidentified) cause the nasal aspect of the lower eyelid) as well as mucoid of dacryocystitis: In an afebrile child with a mild case, 20 or purulent discharge when digital pressure is applied to to 40 mg/kg of oral amoxicillin-clavulanate taken daily the area.1-3 This most commonly occurs in infants and in in 3 divided doses will suffice. -

OPTOMETRIC PHYSICIAN SYMPOSIUM January 26Th, 2019

30TH Annual OPTOMETRIC PHYSICIAN SYMPOSIUM January 26th, 2019 Anterior Segment Grand Rounds Blair Lonsberry, O.D., FAAO 1/25/2019 Dendritic Ulcers Case • 20 year old male presents with a red painful eye – Started that morning when he woke up – reports a watery discharge, no itching, and is not a contact lens wearer • SLE: – See attached image with NaFl stain 3 Herpes Simplex Keratitis: Clinical Features • Characterized by primary outbreak and subsequent reactivation • Primary outbreak is typically mild or subclinical • After primary infection, the virus becomes latent in the trigeminal ganglion or cornea • Stress, UV radiation, and hormonal changes can reactivate the virus • Lesions are common in the immunocompromised (i.e. recent organ transplant or HIV patients) 1 1/25/2019 Anti‐Viral Medication Pediatric HSV Keratitis Drug Mechanism of Action Bioavailability Dosing Side Effects Acyclovir Acyclovir interferes 10‐30% gets Simplex: Overall very safe • pediatric herpes simplex keratitis has an 80% risk with DNA synthesis absorbed 400 mg Nausea, of recurrence, a 75% risk of stromal disease, and inhibiting viral Short ½ life 5x/day vomiting, a 30% rate of misdiagnosis replication *Metabolized in Zoster: headaches, kidneys 800 mg dizziness, • 80% of children with herpes simplex keratitis 5x/day confusion develop scarring, mostly in the central cornea Valacyclovir Acyclovir pro‐drug 95% converted Simplex: Same as acyclovir – results in the development of astigmatism Equivalent to acyclovir to acyclovir* 500 mg tid but better for pain Better