River Piracy and Drainage Basin Reorganization Led by Climate-Driven Glacier Retreat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tatshenshini River Ten Year Monitoring Report Prepared

Tatshenshini River Ten Year Monitoring Report Prepared for: Yukon Parks Department of Environment Government of Yukon Whitehorse, Yukon Prepared by: Bruce K. Downie PRP Parks: Research & Planning Whitehorse, Yukon Purpose of the Report The Tatshenshini River was designated as a Canadian Heritage River in 2004. The Canadian Heritage River System requires regular monitoring of the natural, heritage and recreational values underpinning each designation. This report presents the results of the ten year review of the river values and key elements of the management strategies for the Yukon portion of the Tatshenshini watershed. The report also points out which characteristics and qualities of the designated river have been maintained as well as the activities and management actions that have been implemented to ensure the continued integrity of the river’s values. And, finally, the report also highlights issues that require further attention in order to maintain the heritage values of the designation. On the basis of these findings, the report assesses the designation status of the Tatshenshini River within the Canadian Heritage River System. Acknowledgements Thanks are due to the those individuals consulted through this analysis and especially to the dedicated individuals in Yukon and First Nations governments who continue to work towards the protection of the natural and cultural values and the wilderness recreational opportunities of the Tatshenshini River. Appreciation is also extended to Parks Canada and the Canadian Heritage Rivers Board Secretariat for their assistance and financial support of this review. All photos provided by: Government of Yukon ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PRP Parks: Research & Planning - 2 - March, 2014 Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................................ -

Literaturverweise

Literaturverweise Statt eines Vorworts: Das Corona-Experiment 1. Le Quéré, C., Jackson, R. B., Jones, M. W., Smith, A. J. P., Abernethy, S., Andrew, R. M., De-Gol, A. J., Willis, D. R., Shan, Y., Canadell, J. G., Friedlingstein, P., Creutzig, F., Peters, G. P. (2020): Temporary reduction in daily global CO2 emissions during the COVID-19 forced confinement: Nature Climate Change 10 (7), 647-653. 2. Myllyvirta, L. (2020): Coronavirus temporarily reduced China’s CO2 emissions by a quarter. Carbon Brief https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-coronavirus-has- temporarily-reduced-chinas-co2-emissions-by-a-quarter 3. Spencer, R.(2020): Why the current Economics slowdown won’t show up in the atmospheric record, https://www.drroyspencer.com/2020/05/why-the-current- economic-slowdown-wont-show-up-in-the-atmospheric-co2-record/ 4. Die Abbauzeit (Lebensdauer) des CO2 ist die Zeit , in der die Konzentration auf ein 1/e (0,3679) des Ausgangswerts gesunken ist. Sie wird berechnet als Quotient des zum Gleichgewicht von 280 ppm hinzugefügten CO2 durch die Größe des Abbaus. 1959 waren das 34 ppm : 0,64 ppm = 55 Jahre. 2019 sind das 130 ppm : 2,6 ppm =50 Jahre. Die Umrechnung in einen Abbau von 50 % (Halbwertszeit) gelingt durch Multiplikation dieser Abbauzeiten mit ln2 = 0,6931. Das sind dann 1959 38 Jahre und 2019 34,7 Jahre. 5. Haverd, V., Smith, B., Canadell, J. G., Cuntz, M., Mikaloff-Fletcher, S., Farquhar, G., Woodgate, W., Briggs, P. R., Trudinger, C. M. (2020): Higher than expected CO2 fertilization inferred from leaf to global observations: Global Change Biology 26 (4), 2390-2402. -

Tatshenshini and Alsek Rivers of Alaska

ASSESSING THE RISKOF BEAR-HUMANINTERACTION AT RIVERCAMPSITES A. GRANTMacHUTCHON, 237 CurtisRoad, Comox,BC V9M3W1, Canada, email: [email protected] DEBBIEW. WELLWOOD, P.O. Box 3217, Smithers,BC VOJ2N0, Canada,email: [email protected] Abstract: The Alsek and Tatshenshinirivers of Yukon, British Columbia, and Alaska, and the Babine River, British Columbia, are seasonally importantfor grizzly bears(Ursus arctos) and Americanblack bears(Ursus americanus). Recreationaltravelers on these rivers use riparianhabitats for camping, which could lead to bear-humaninteraction and conflict. During visits in late summer 1998-99, we used 4 qualitativeindicators to assess risk of bear-humaninteraction at river campsites: (1) seasonal habitatpotential, (2) travel concerns, (3) sensory concerns, and (4) bear sign. We then rated each campsite on a 5-class scale, relative to other campsites, for the potential to displace bears and the potential for bear-human encounters. We used these ratingsto recommendhuman use of campsites with relatively low risk. Ursus 13:293-298 (2002) Key words: Alaska,American black bear, bear-human conflict, British Columbia, grizzly bear, habitat assessment, river recreation, Ursus americanus, Ursus arctos, Yukon Riparianhabitats in manyriver valleys in westernNorth 1997). The Tatshenshiniand Alsek river valleys com- America are seasonally important for grizzly bears prise a large proportionof available bear habitatwithin (Hamilton and Archibald 1986, Reinhart and Mattson the parksthrough which they flow, and the importanceof 1990, MacHutchon et al. 1993, Schoen et al. 1994, riparianhabitats to bearsis high (Simpson 1992, Herrero McCann 1998, Titusand Beier 1999) andAmerican black et al. 1993, McCann 1998). The main period of human bears (Reinhartand Mattson 1990, MacHutchonet al. use coincides with seasonalmovement of grizzly bearsto 1998, Chi and Gilbert 1999). -

GSIS Newsletter Will Be Published Quarterly, in March, June, September, and December by the Geoscience Information Society

Number 256, December, 2012 ISSN: 0046-5801 CONTENTS Presidents Column…………………………………………………………. 1 Open access publication opportunities for geoscientists……………….. 13 Geoscience Information Society 2012 Officers……………………………. 2 Annual meeting pictures……………………………………………….. 18 Member updates……………………………………………………………. 3 GeoScienceWorld Unveils Open, Map-Based Discovery Prototype…... 20 Greetings from Australia…………………………………………………... 3 Auditor’s Report for 2010……………………………………………… 21 Geoscience journal prices………………………………………………….. 5 Issue to watch: AGU partners with Wiley-Blackwell………………….. 21 GSIS Publications List…………………………………………………. 22 President's Column By Linda Zellmer Now that we have all returned from the meeting the past year: in Charlotte and (in the case of the members in the United States) eaten our Thanksgiving • April Love and Cynthia Prosser - for setting Dinners, we are probably making our lists for up the GSIS Exhibit holiday gifts. While I do not have any gifts to • Clara McLeod - for coordinating Geoscience give out, I would like to take the opportunity to Librarianship 101 (GL 101). offer my heartfelt appreciation to all of the • Amanda Bielskas – for teaching the people who have contributed to the efforts of Collection Development portion of GL 101. Geoscience Information Society during the past • Hannah Winkler - for teaching the year and our recent meeting. Reference Services portion of GL101. • Megan Sapp-Nelson – for developing a presentation on Library Instruction for the We had 5 sponsors for our meeting who Earth Sciences that I presented for her at GL provided funding to help defray the costs of the 101. meeting. They include: American Association of • Adonna Fleming – for helping with publicity Petroleum Geologists, Geoscience World, for GL 101. Gemological Institute of America, Geological • Jan Heagy – for developing certificates of Society of London and Elsevier. -

Final Wild and Scenic River Stu8y N .. + R-E~O--L

Nf s 1-:: ~' { c" ~ 1 - final wild and scenic river stu8y N .. + R-e~o --L october 1982 ALASKA U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE FINAL WILD AND SCENIC RIVER REPORT FOR THE MELOZITNA RIVER, ALASKA Pursuant to Section S(a) of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, Public Law 90-542, as amended, the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, has prepared a report for the Melozitna Wild and Scenic River Study. This report presents an evaluation and analysis of the Melozitna River and the finding that the river does not meet the criteria of eligibility for inclusion into the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. A limited number of copies are available upon request to: Regional Director Alaska Regional Office National Park Service 2525 Gambell Street, Room 107 Anchorage, Alaska 99503-2892 (907) 271-4196 TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover Sheet i Summary of Findings and Conclusions 1 Findings 1 Conclusions 1 Introduction 1 Purpose of Study 1 Conduct of Study 2 The Melozitna River Region 2 Location and Topography 2 Climate 4 Land Ownership 4 Land Use 6 Socioeconomic Conditions 6 Population Centers 6 Economy 7 Transportation and Access 7 The Melozitna River Study Area 8 Cultural Resources 8 Fish and Wildlife 9 Geology and Mineral Resources 10 Recreation 12 Scenic Resources 13 Stream Flow Characteristics and Water Quality 14 Water Resource Developments 16 Other Possible Actions 16 Consultation and Coordination of the Draft Report 17 Comments Received 18 Abbreviations ADF&G - Alaska Department of Fish and Game ANILCA - Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act BLM - Bureau of Land Management FWS - Fish and Wildlife Service NPS - National Park Service WSR - Wild and Scenic River F. -

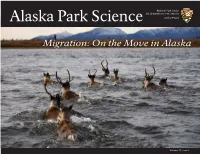

Migration: on the Move in Alaska

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Alaska Park Science Alaska Region Migration: On the Move in Alaska Volume 17, Issue 1 Alaska Park Science Volume 17, Issue 1 June 2018 Editorial Board: Leigh Welling Jim Lawler Jason J. Taylor Jennifer Pederson Weinberger Guest Editor: Laura Phillips Managing Editor: Nina Chambers Contributing Editor: Stacia Backensto Design: Nina Chambers Contact Alaska Park Science at: [email protected] Alaska Park Science is the semi-annual science journal of the National Park Service Alaska Region. Each issue highlights research and scholarship important to the stewardship of Alaska’s parks. Publication in Alaska Park Science does not signify that the contents reflect the views or policies of the National Park Service, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute National Park Service endorsement or recommendation. Alaska Park Science is found online at: www.nps.gov/subjects/alaskaparkscience/index.htm Table of Contents Migration: On the Move in Alaska ...............1 Future Challenges for Salmon and the Statewide Movements of Non-territorial Freshwater Ecosystems of Southeast Alaska Golden Eagles in Alaska During the A Survey of Human Migration in Alaska's .......................................................................41 Breeding Season: Information for National Parks through Time .......................5 Developing Effective Conservation Plans ..65 History, Purpose, and Status of Caribou Duck-billed Dinosaurs (Hadrosauridae), Movements in Northwest -

List Stranica 1 Od

list product_i ISSN Primary Scheduled Vol Single Issues Title Format ISSN print Imprint Vols Qty Open Access Option Comment d electronic Language Nos per volume Available in electronic format 3 Biotech E OA C 13205 2190-5738 Springer English 1 7 3 Fully Open Access only. Open Access. Available in electronic format 3D Printing in Medicine E OA C 41205 2365-6271 Springer English 1 3 1 Fully Open Access only. Open Access. 3D Display Research Center, Available in electronic format 3D Research E C 13319 2092-6731 English 1 8 4 Hybrid (Open Choice) co-published only. with Springer New Start, content expected in 3D-Printed Materials and Systems E OA C 40861 2363-8389 Springer English 1 2 1 Fully Open Access 2016. Available in electronic format only. Open Access. 4OR PE OF 10288 1619-4500 1614-2411 Springer English 1 15 4 Hybrid (Open Choice) Available in electronic format The AAPS Journal E OF S 12248 1550-7416 Springer English 1 19 6 Hybrid (Open Choice) only. Available in electronic format AAPS Open E OA S C 41120 2364-9534 Springer English 1 3 1 Fully Open Access only. Open Access. Available in electronic format AAPS PharmSciTech E OF S 12249 1530-9932 Springer English 1 18 8 Hybrid (Open Choice) only. Abdominal Radiology PE OF S 261 2366-004X 2366-0058 Springer English 1 42 12 Hybrid (Open Choice) Abhandlungen aus dem Mathematischen Seminar der PE OF S 12188 0025-5858 1865-8784 Springer English 1 87 2 Universität Hamburg Academic Psychiatry PE OF S 40596 1042-9670 1545-7230 Springer English 1 41 6 Hybrid (Open Choice) Academic Questions PE OF 12129 0895-4852 1936-4709 Springer English 1 30 4 Hybrid (Open Choice) Accreditation and Quality PE OF S 769 0949-1775 1432-0517 Springer English 1 22 6 Hybrid (Open Choice) Assurance MAIK Acoustical Physics PE 11441 1063-7710 1562-6865 English 1 63 6 Russian Library of Science. -

TH Best Practices for Heritage Resources

Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Best Practices for HeritageHeading Resources Place your message here. For maximum impact, use two or three sentences. March 2011 Scope This manual provides the First Nation perspective on working with heritage resources in Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Traditional Territory. It is not intended as a legal document or to supplant any regulatory frameworks within the Yukon. This is not a comprehensive guide nor is it intended to be static. These best practices represent the best information and resources currently available. The Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Heritage Department consists of specialists in heritage sites, land-based heritage resources, language, traditional knowledge, and collections management. We are both capable and enthusiastic to work with industry to protect First Nation cultural heritage. It is the role of this department to represent and safeguard the heritage and culture of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in. The Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Heritage Department has proven that working cooperatively with proponents of the mining, development, resource, and industrial sectors is mutually beneficial and assists everyone in meeting their goals. We welcome inquiries from all project proponents. Early collaboration facilitates proper management and protection of our heritage resources. Contact: Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Heritage Department PO Box 599 Dawson City, Yukon Y0B 1G0 Phone: (867) 993-7113 Fax: (867) 993-6553 Toll-Free: 1-877-993-3400 Cover Photo: Tro’chëk, 2004. 2 Table of Contents Objectives …………………………………………………………………………………………………………..… 4 Legislative Framework ………………………………………………………………………………………… 5 Cultural Context …………………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Heritage ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 8 Protecting Heritage Resources …………………………………………………………………………… 10 Reporting …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….… 14 References: Useful Resources, Legislation, Policy, and Best Practices …………… 15 Cut stump recorded during a 2005 heritage Julia Morberg harvesting blueberries. -

A Family Float Trip Down the Yukon River by John Morton

Refuge Notebook • Vol. 10, No. 39 • October 17, 2008 A family float trip down the Yukon River by John Morton the Yukon Quest. But it’s equally challenging when young kids are involved and you’re worried about making sure they’re having fun and are SAFE. This is a tall order when they’re inhaling mosquitoes, pad- dling through water as cold as ice with big hydraulics or camping in bear country. Our “wilderness” trip got a rocky start as we passed a sign below Whitehorse that cautioned about treated effluent being discharged into the river. Sev- eral miles below town we ran into a grocery cart stick- ing out of a muddy bar in a bend on the river. As we paddled across the 30-mile long Lake Lebarge, made famous by Robert Service’s poetic celebration of the Cremation of Sam McGee, we saw abundant signs of humans everywhere: tent sites, rusted cans, old cables, and broken glass. But gradually these modern archaeological arti- facts disappear as we get into dining on grayling and wild onions further down the river. Saxifrage, blue- Straight off the water to the telephone, Mika Morton, 11, bells, cinquefoil, wild sweet pea, and fleabane are flow- reconnects with civilization in Eagle after 700 miles on ering everywhere. Ravens stick their heads into the the Yukon River. Her sister Charly, 6, is not in such a holes of cliff and bank swallows to feed on nestlings rush. The Morton family made the 4-week wilderness and eggs. As we pass one of many spectacular cliffs trip from Whitehorse, Yukon Territory to Eagle, Alaska along the river, a pair of peregrine falcons double by canoe in June. -

Northern Climate Exchange, 2013. Burwash Landing and Destruction Bay Landscape Hazards: Geological Mapping for Climate Change Adaptation Planning

Community Adaptation Project BURWASH LANDING AND DESTRUCTION BAY LANDSCAPE HAZARDS: GEOLOGICAL MAPPING FOR CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION PLANNING April 2013 COMMUNITY ADAPTATION PROJECT BURWASH LANDING AND DESTRUCTION BAY LANDSCAPE HAZARDS: GEOLOGICAL MAPPING FOR CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION PLANNING April 2013 Printed in Whitehorse, Yukon, 2013 by Integraphics Ltd, 411D Strickland St. This publication may be obtained from: Northern Climate ExChange c/o Yukon Research Centre, Yukon College 500 College Drive PO Box 2799 Whitehorse, YT Y1A 5K4 Supporting research documents that were not published with this report may also be obtained from the above address. Recommended citation: Northern Climate ExChange, 2013. Burwash Landing and Destruction Bay Landscape Hazards: Geological Mapping for Climate Change Adaptation Planning. Yukon Research Centre, Yukon College, 111 p. and 2 maps. Production by Leyla Weston, Whitehorse, Yukon. Front cover photograph: Burwash Landing, with Kluane Lake in the foreground and the Kluane Range in the background; view is looking southeast from Dalan campground. Photo courtesy of Northern Climate ExChange Foreword The Kluane First Nation is made up of strong and inspired people, who have lived in their Traditional Territory since time immemorial. Their Territory spans an area between the White River to the north, and the Slims River to the south; and from the St. Elias Mountains to the west, to the Ruby Ranges to the east. We have seen many changes on the land and in our community - from the establishment of the Alaska Highway, to the inception of the Kluane First Nation Government; all the while, we remain present with the land. Today, we are witnessing changes in our climate that are reflected on the land, and so we must take action to address the needs of our future generations. -

1 Assessment of 2020 Mixed-Stock Fisheries for Coho Salmon in Northern and Central British

1 1 Assessment of 2020 mixed-stock fisheries for coho salmon in northern and central British 2 Columbia, Canada via parentage-based tagging and genetic stock identification 3 4 Terry D. Beacham and Eric B. Rondeau 5 6 7 Fisheries and Oceans Canada, 8 Pacific Biological Station, 9 3190 Hammond Bay Road, Nanaimo, B. C. 10 Canada V9T 6N7 11 12 Final Report, May 2021 13 14 15 16 A project funded by the Northern Boundary Restoration and Enhancement Fund 2020-2021. 17 2 18 Abstract 19 Genetic stock identification (GSI) and parentage-based tagging (PBT) are being 20 increasingly applied to salmon fisheries and hatchery broodstock management and assessment in 21 Canada. GSI and PBT were applied to assessment of 2019 coho salmon fisheries northern and 22 central British Columbia (BC), Canada. The catch from northern freezer troll (Area F) and ice 23 boat troll (Area F), recreational catch in Statistical Areas 3/4, the lower Skeena River test fishery 24 at Tyee, and the Heiltsuk First Nation food, social, and ceremonial fishery near Bella Bella on 25 the central coast of BC were sampled. There were 1,223 individuals successfully genotyped 26 from fishery samples and 4 parentage-based tagging identifications made. The large majority of 27 the catch in the northern troll fishery was derived from northern and central coast Conservation 28 Units. 3 29 Introduction 30 Coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) are caught in commercial, recreational, and First 31 Nations fisheries in British Columbia, and determination of the impact of these fisheries is of 32 fundamental importance to status assessment for wild populations and management of large- 33 scale hatchery production. -

Geographic Names

GEOGRAPHIC NAMES CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES ? REVISED TO JANUARY, 1911 WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1911 PREPARED FOR USE IN THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE BY THE UNITED STATES GEOGRAPHIC BOARD WASHINGTON, D. C, JANUARY, 1911 ) CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES. The following list of geographic names includes all decisions on spelling rendered by the United States Geographic Board to and including December 7, 1910. Adopted forms are shown by bold-face type, rejected forms by italic, and revisions of previous decisions by an asterisk (*). Aalplaus ; see Alplaus. Acoma; township, McLeod County, Minn. Abagadasset; point, Kennebec River, Saga- (Not Aconia.) dahoc County, Me. (Not Abagadusset. AQores ; see Azores. Abatan; river, southwest part of Bohol, Acquasco; see Aquaseo. discharging into Maribojoc Bay. (Not Acquia; see Aquia. Abalan nor Abalon.) Acworth; railroad station and town, Cobb Aberjona; river, IVIiddlesex County, Mass. County, Ga. (Not Ackworth.) (Not Abbajona.) Adam; island, Chesapeake Bay, Dorchester Abino; point, in Canada, near east end of County, Md. (Not Adam's nor Adams.) Lake Erie. (Not Abineau nor Albino.) Adams; creek, Chatham County, Ga. (Not Aboite; railroad station, Allen County, Adams's.) Ind. (Not Aboit.) Adams; township. Warren County, Ind. AJjoo-shehr ; see Bushire. (Not J. Q. Adams.) Abookeer; AhouJcir; see Abukir. Adam's Creek; see Cunningham. Ahou Hamad; see Abu Hamed. Adams Fall; ledge in New Haven Harbor, Fall.) Abram ; creek in Grant and Mineral Coun- Conn. (Not Adam's ties, W. Va. (Not Abraham.) Adel; see Somali. Abram; see Shimmo. Adelina; town, Calvert County, Md. (Not Abruad ; see Riad. Adalina.) Absaroka; range of mountains in and near Aderhold; ferry over Chattahoochee River, Yellowstone National Park.