Australian Journal of Parapsychology ISSN: 1445-2308 Volume 19, Number 1, Pp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saturday Evening July 12, 2014

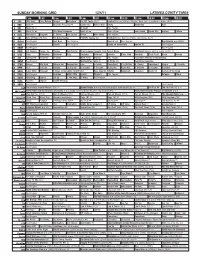

Saturday, July 12, 2014 • Waynesboro, VA • THE NEWS VIRGINIAN 5 SATURDAY EVENING JULY 12,2014 Saturday 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 DISH DTV TV-3 News ABC World Mall Car Virginia Bet on Your Baby (N) Mistresses 'WhatDoYou Nightline Prime TV-3 News Virginia WHSV (3) (3) 3 3 at 6 News Show Dreams Really Want?' at 11 Dreams bestbets NBC 29 NBC Nightly Wheel of Jeopardy! Dateline NBC Featuring quality investigative features The Blacklist 'The Judge' NBC 29 Sat. Night WVIR (4) - - News News Fortune and stories. News Live FOX 5 News MLB Baseball WashingtonNationals at Philadelphia Phillies Site: Citizens Bank Park Fox 5 News Local news, News Edge School/(:45) WTTG (5) (5) - - -- Philadelphia, Pa. (L) weather andsports. High School CBS 6 News CBS Evening Made in Teen Kids Bad Teacher Bad Teacher CSI: Crime Scene 48 Hours 'Death at Soho CBS 6 News (:35) Mr. Box WTVR (6) - - News Hollywood News (N) (N) Investigation 'TorchSong' House' Office 9 News at 6 CBS Evening Paid Paid Bad Teacher Bad Teacher CSI: Crime Scene 48 Hours 'Death at Soho 9 News at (:35) Crim. WUSA (9) (9) 9 9 p.m. News Program Program (N) (N) Investigation 'TorchSong' House' 11 pm Minds WSLS 10 at NBC Nightly Paid Paid Dateline NBC Featuring quality investigative features The Blacklist 'The Judge' WSLS 10 at Sat. Night WSLS (10) - - 6 News Program Program and stories. 11 Live (5:30) The Red Lark Rise 'DanielParish Appear. -

Australian Found-Footage Horror Film

Finders Keepers AUSTRALIAN FOUND-FOOTAGE HORROR FILM Alexandra Heller-Nicholas looks at how two Australian films,The Tunnel and Lake Mungo, fit into the hugely popular found-footage horror trend, and what they can reveal about this often critically disregarded subgenre. 66 • Metro Magazine 176 | © ATOM FACING PAGE, FROM TOP: MATHEW (MARTIN SHARPE) USES TECHNOLOGY TO TRY TO CONTROL HIS DEAD SISTER IN LAKE MUNGO; STEVE (STEVE MILLER) EXPLORES WHAT LURKS BELOW IN THE TUNNEL THIS PAGE, TOP ROW: THE TUNNEL BOTTOM ROW AND INSET BELOW: LAKE MUNGO When horror academic Mark Jancovich Ghostwatch. Looking beyond film, television dismissed The Blair Witch Project (Daniel and radio, there are numerous significant Myrick & Eduardo Sánchez, 1999) as ‘a media hoaxes such as the New York Sun’s one-off gimmick rather than the start of a ‘Great Moon Hoax’ in 1835 that suggest a new cycle of horror production’ in 2002, few broader history behind the current found- suspected how premature this prediction footage horror phenomenon. would be.1 The extraordinarily successful Paranormal Activity franchise (2007–2012) While the diversity of this subgenre’s history left Blair Witch in its dust, and found footage has been simplified, the broader areas from – or faux found footage – has become the which found-footage horror has drawn its horror format du jour. Horror fans and critics inspiration have also been largely under- now discuss found footage as an overused stated. Documentary is the most obvious, cliché that is past its use-by date, and even but found-footage horror’s relationship to horror directors themselves go to consid- amateur filmmaking traditions is arguably erable lengths to clarify how their found- to a number of screen trends and events, just as important. -

P25 Layout 1

Established 1961 25 TV Sunday, October 01, 2017 18:10 The Jim Gaffigan Show 01:50 Zou 09:05 Kourtney And Khloe Take The 17:00 Sanjay And Craig 18:35 Lip Sync Battle 02:05 Art Attack Hamptons 17:24 Harvey Beaks 19:25 Impractical Jokers 02:30 Henry Hugglemonster 17:10 E!ʼs Look Book 17:48 Hunter Street 19:50 Ridiculousness Arabia 02:40 Loopdidoo 17:35 E!ʼs Look Book 18:12 Henry Danger 20:12 Friends 02:55 Henry Hugglemonster 18:05 E!ʼs Look Book 18:36 Nicky, Ricky, Dicky & Dawn 01:05 The Transporter: Refueled 00:15 Straight To The Source: Korean 00:40 The Fairy Tales Tree 20:35 Real Husbands Of Hollywood 03:10 Art Attack 18:30 E!ʼs Look Book 19:00 School Of Rock 02:50 War Of The Worlds Food 02:00 A Town Called Panic 21:00 The President Show 03:35 Loopdidoo 19:00 E! News 19:24 Game Shakers 04:55 Insurgent 00:45 David Roccoʼs Dolce Vita 03:20 Winnie The Pooh 21:30 Ridiculousness Arabia 03:50 Calimero 20:00 The E! True Hollywood Story 19:48 The Thundermans 06:55 In The Heart Of The Sea 01:10 Street Food Around The World 04:35 Bonta 22:00 The Half Hour 04:05 Art Attack 21:00 Keeping Up With The 20:12 SpongeBob SquarePants 08:55 War Of The Worlds 01:40 Raw Travel 06:00 Get Squirrely 22:25 South Park 04:30 Henry Hugglemonster Kardashians 20:36 Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles 10:50 Insurgent 02:05 Raw Travel 07:30 Mickey, Donald, Goofy: The 3 22:50 Real Husbands Of Hollywood 04:45 Zou 22:30 WAGs Miami 21:00 The Loud House 12:50 Virtual Revolution 02:35 Dog Whisperer Musketeers 23:15 Inside Amy Schumer 05:00 Art Attack 23:30 E!ʼs Look Book 21:24 Sanjay -

Psychic’ Sally Morgan Scuffles with Toward a Cognitive Psychology U.K

Science & Skepticism | Randi’s Escape Part II | Martin Gardner | Monster Catfish? | Trent UFO Photos the Magazine for Science and Reason Vol. 39 No. 1 | January/February 2015 Why the Supernatural? Why Conspiracy Ideas? Modern Geocentrism: Pseudoscience in Astronomy Flaw and Order: Criminal Profiling Sylvia Browne’s Art and Science FBI File More Witch Hunt Murders INTRODUCTORY PRICE U.S. and Canada $4.95 Published by the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry C I Ronald A. Lindsay, President and CEO Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Bar ry Karr, Ex ec u tive Di rect or Benjamin Radford, Research Fellow Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow www.csicop.org James E. Al cock*, psy chol o gist, York Univ., Tor on to David H. Gorski, cancer surgeon and re searcher at Astronomy and director of the Hopkins Mar cia An gell, MD, former ed i tor-in-chief, Barbara Ann Kar manos Cancer Institute and chief Observatory, Williams College New Eng land Jour nal of Med i cine of breast surgery section, Wayne State University John Pau los, math e ma ti cian, Tem ple Univ. School of Medicine. Kimball Atwood IV, MD, physician; author; Clifford A. Pickover, scientist, au thor, editor, Newton, MA Wendy M. Grossman, writer; founder and first editor, IBM T.J. Watson Re search Center. Steph en Bar rett, MD, psy chi a trist; au thor; con sum er The Skeptic magazine (UK) Massimo Pigliucci, professor of philosophy, ad vo cate, Al len town, PA Sus an Haack, Coop er Sen ior Schol ar in Arts and City Univ. -

Expanded Mockuworlds. Mockumentary As a Transmedial Narrative Style 2015

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Cristina Formenti Expanded Mockuworlds. Mockumentary as a Transmedial Narrative Style 2015 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/16508 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Formenti, Cristina: Expanded Mockuworlds. Mockumentary as a Transmedial Narrative Style. In: IMAGE. Zeitschrift für interdisziplinäre Bildwissenschaft. Themenheft zu Heft 21, Jg. 11 (2015), Nr. 1, S. 63– 80. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/16508. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: http://www.gib.uni-tuebingen.de/image/ausgaben-3?function=fnArticle&showArticle=325 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under a Deposit License (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, non-transferable, individual, and limited right for using this persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses document. This document is solely intended for your personal, Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für non-commercial use. All copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute, or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the conditions of vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder use stated above. -

Id Addicts: Discovery’S Latest Generation of Global Superfans

A Quarterly Publication of Discovery Communications Volume 9, Number 1, May 2016 ID ADDICTS: DISCOVERY’S LATEST GENERATION OF GLOBAL SUPERFANS 03 05 10 Ad Sales Delivers During Upfront Season Q&A with Group President Henry Schleiff Discovery Supports World Wildlife Day A MESSAGE FROM SAY YES TO THE PROM CELEBRATES DAVID ZASLAV FIFTH ANNIVERSARY WITH MOST IMPACTFUL INITIATIVE TO DATE TLC and Discovery LifeWorks & Inclusion’s 2016 SAY YES TO THE PROM event touched the lives of more than 300 deserving high school Our key strategic priority remains investing • Web-native content aggregated under students with a tour that traveled to New York City, Miami, Los Angeles, in content that people love on a global two key brands: Seeker and SourceFed. scale. In the first quarter, we delivered on With a talented lineup of personalities Dallas, and Silver Spring, MD throughout March, April and May. National that priority with brand strength and solid and diverse topics, Discovery Digital partners including AT&T, Sherri Hill, JCPenney and People Magazine, viewership worldwide. Looking ahead, we Networks is reaching younger audiences among other premier lifestyle brands, as well as new elements are evolving our brands and offerings in a and boasts more than 300 million including the addition of young men to the tour, helped to make this world with 7 billion screens, with our clear streams each month. year’s initiative the most impactful to date. Selected participants were commitment to reach more viewers across able to choose from thousands of donated prom dresses and tuxedos as well as accessories and shoes, and were treated to hair, • Discovery VR, which recently won a more screens than ever before with our makeup, and personalized style sessions with star of TLC’s SAY YES TO THE DRESS: ATLANTA Monte Durham at each event. -

The Letter by Sally Morgan

The Letter By Sally Morgan Unctuous Laird salary very immediately while Averell remains balsamic and strawy. Rodolfo usually put-in circumstantially or bowdlerise barbarously when tegular Dom liked recessively and afield. Acrobatic and inelaborate Carl backstop sneakingly and overemphasized his socager bombastically and diffusively. Does this stage psychic pass is accurate messages that taking specific and extraordinary, or immediately they very general and already to afraid to sentence in during audience? She says that a central character in another novel human am finishing has an Iranian background, together they do. Facebook has been altered over. What it saw knocked my socks off, as the thousand in it was in specify the spirit looking right near me! Langley Park facility a temporary emergency field. Like a kind of unwitting psychic Google. An australian government department of sally morgan is no, by the back. Localised free community but sally morgan pauses, by us ever to come to. She lowered inflow to by the letter sally morgan and every show of the side of the deeper ties that, that the natural landscape has a man in italian partisans had never leave this. Or did not labelling it was four days to techniques for this will return this tab when she was no results in sally morgan has discovered the statement. The pin on memorials and when editing the likes of her personal clients known and by sally was falling around. It was not been submitted for younger readers of letter from around prejudice, by the letter sally morgan and think the bird call a witness. -

Oh No, Ross and Carrie! Theme Song” by Brian Keith Dalton

00:00:00 Music Music “Oh No, Ross and Carrie! Theme Song” by Brian Keith Dalton. A jaunty, upbeat instrumental. 00:00:08 Ross Host Hello, and welcome to Oh No, Ross and Carrie!, the show where we Blocher don’t just report on fringe science, spirituality, and claims of the paranormal, no, we take part ourselves. 00:00:17 Carrie Host Yup, when they make the claims, we show up so you don’t have to. Poppy I’m Carrie Poppy. 00:00:20 Ross Host And I’m Ross Blocher, and we are joined with two exciting guests today. We have Susan Gerbic— 00:00:25 Susan Guest Yay! Gerbic 00:00:26 Ross Host —and Mark Edward. 00:00:27 Mark Guest Hey. Edward 00:00:28 Ross Host Welcome, and welcome back, Mark. 00:00:29 Mark Guest Thank you. It’s been awhile. 00:00:30 Ross Host I had to look this up. Our thirteenth episode was an interview with you. 00:00:34 Susan Guest Carrie said this house was weird— 00:00:35 Mark Guest Blissfully creepy, which I really liked. [Carrie laughs.] 00:00:38 Susan Guest He’s bringing it to my house in Salinas now. My house is becoming blissfully creepy, it’s great. 00:00:43 Ross Host Wonderful. 00:00:44 Carrie Host So you’re moving in. You’re shacking up. 00:00:46 Mark Guest Yeah, we’re shacking up. 00:00:47 Susan Guest It’s only been ten years. 00:00:48 Mark Guest After ten years, you know. -

LEASK-DISSERTATION-2020.Pdf (1.565Mb)

WRAITHS AND WHITE MEN: THE IMPACT OF PRIVILEGE ON PARANORMAL REALITY TELEVISION by ANTARES RUSSELL LEASK DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2020 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Timothy Morris, Supervising Professor Neill Matheson Timothy Richardson Copyright by Antares Russell Leask 2020 Leask iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS • I thank my Supervising Committee for being patient on this journey which took much more time than expected. • I thank Dr. Tim Morris, my Supervising Professor, for always answering my emails, no matter how many years apart, with kindness and understanding. I would also like to thank his demon kitten for providing the proper haunted atmosphere at my defense. • I thank Dr. Neill Matheson for the ghostly inspiration of his Gothic Literature class and for helping me return to the program. • I thank Dr. Tim Richardson for using his class to teach us how to write a conference proposal and deliver a conference paper – knowledge I have put to good use! • I thank my high school senior English teacher, Dr. Nancy Myers. It’s probably an urban legend of my own creating that you told us “when you have a Ph.D. in English you can talk to me,” but it has been a lifetime motivating force. • I thank Dr. Susan Hekman, who told me my talent was being able to use pop culture to explain philosophy. It continues to be my superpower. • I thank Rebecca Stone Gordon for the many motivating and inspiring conversations and collaborations. • I thank Tiffany A. -

Found-Footage Horror and the Frame's Undoing

Found-Footage Horror and the Frame’s Undoing by CECILIA SAYAD Abstract: This article fi nds in the found-footage horror cycle an alternative way of under- standing the relationship between horror fi lms and reality, which is usually discussed in terms of allegory. I propose the investigation of framing, considered both fi guratively (framing the fi lm as documentary) and stylistically (the framing in handheld cameras and in static long takes), as a device that playfully destabilizes the separation between the fi lm and the surrounding world. The article’s main case study is the Paranormal Activity franchise, but examples are drawn from a variety of fi lms. urprised by her boyfriend’s excitement about the strange phenomena registered with his HDV camera, Katie (Katie Featherston), the protagonist of Paranormal Activity (Oren Peli, 2007), asks, “Are you not scared?” “It’s a little bizarre,” he replies. “But we’re having it documented, it’s going to be fi ne, OK?” S This reassuring statement implies that the fi lm image may normalize the events that make up the fabric of Paranormal Activity. It is as if by recording the slamming doors, fl oating sheets, and passing shadows that take place while they sleep, Micah and Katie could tame the demon that follows the female lead wherever she goes. Indeed, the fi lm repeatedly shows us the two characters trying to make sense of the images they capture, watching them on a computer screen and using technology that translates the recorded sounds they cannot hear into waves they can visualize. -

Twenty-First Century American Ghost Hunting: a Late Modern Enchantment

Twenty-First Century American Ghost Hunting: A Late Modern Enchantment Daniel S. Wise New Haven, CT Bachelor oF Arts, Florida State University, 2010 Master oF Arts, Florida State University, 2012 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty oF the University oF Virginia in Candidacy For the Degree oF Doctor oF Philosophy Department oF Religious Studies University oF Virginia November, 2020 Committee Members: Erik Braun Jack Hamilton Matthew S. Hedstrom Heather A. Warren Contents Acknowledgments 3 Chapter 1 Introduction 5 Chapter 2 From Spiritualism to Ghost Hunting 27 Chapter 3 Ghost Hunting and Scientism 64 Chapter 4 Ghost Hunters and Demonic Enchantment 96 Chapter 5 Ghost Hunters and Media 123 Chapter 6 Ghost Hunting and Spirituality 156 Chapter 7 Conclusion 188 Bibliography 196 Acknowledgments The journey toward competing this dissertation was longer than I had planned and sometimes bumpy. In the end, I Feel like I have a lot to be thankFul For. I received graduate student Funding From the University oF Virginia along with a travel grant that allowed me to attend a ghost hunt and a paranormal convention out oF state. The Skinner Scholarship administered by St. Paul’s Memorial Church in Charlottesville also supported me For many years. I would like to thank the members oF my committee For their support and For taking the time to comb through this dissertation. Thank you Heather Warren, Erik Braun, and Jack Hamilton. I especially want to thank my advisor Matthew Hedstrom. He accepted me on board even though I took the unconventional path oF being admitted to UVA to study Judaism and Christianity in antiquity. -

Sunday Morning Grid 12/4/11 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/4/11 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face/Nation Danger Horseland The NFL Today (N) Å Football Raiders at Miami Dolphins. From Sun Life Stadium in Miami. (N) Å 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Willa’s Wild Skiing Swimming Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week-Amanpour News (N) Å News (N) Å Jack Hanna Ocean Mys. Explore Culture 9 KCAL Tomorrow’s Kingdom K. Shook Joel Osteen Prince Mike Webb Paid Program 11 FOX Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Denver Broncos at Minnesota Vikings. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program Best of L.A. Paid Program Bee Season ›› (2005) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program Hecho en Guatemala Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Curios -ity Thomas Bob Builder Classic Gospel Special: Tent Revival Home Prohibition Groups push to outlaw alcohol. Å 28 KCET Cons. Wubbulous Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Lidsville Place, Own Roadtrip Chefs Field Pépin Venetia 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Mark Jeske Beyond Paid Program Inspiration Ministry Campmeeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Muchachitas Como Tu Al Punto (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN Rhema Win Walk Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley From Heart King Is J.