Ecosystem Modeling of the Pryor Mountain Wild Horse Range

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nature Mapping Day 5 Identifying Birds: Anatomy

Nature Mapping Day 5 Identifying Birds: Anatomy Did you see any birds during your nature observation? In Washington State, we observe birds more than any other type of wild vertebrate (animals with a backbone). Think about it. Most people see or hear a wild bird on most days of their life. That can not be said of wild mammals, reptiles, or fish. Once you start noticing birds, most people want to be able to identify what birds they are observing. Often, one of the first things a person notices about a bird is their colors and patterns. Those are called field marks. When you are using field marks, it helps if you know a little bird anatomy. Ornithologists (people who study birds) talk about parts of a bird by dividing its body into regions. The main areas are beak (or bill), head, back, throat, breast, wings, tail, and legs. Many of these regions are divided still further. Purpose: At the end of this lesson I can say with confidence . 1) I can create and use a diagram of a bird’s feathers. Directions: 1) Click on the link below to go to TheCornellLab Bird Academy to learn All About Bird Anatomy. a) https://academy.allaboutbirds.org/features/birdanatomy/ i) Click the -GO!- button to enter the interactive learning tool. ii) Turn each system on or off by using the color-coded boxes. iii) Learn about the individual parts in a system by clicking on the box. The part will be highlighted on the bird diagram. iv) Click on the highlighted section of the bird diagram to learn the function or description of each part and how to pronounce its name. -

Horse and Burro Management at Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Horse and Burro Management at Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge Environmental Assessment Before Horse Gather, August 2004 September 2002 After Horse Gather, August 2005 Front Cover: The left two photographs were taken one year apart at the same site, Big Spring Creek on Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge. The first photograph was taken in August 2004 at the time of a large horse gather on Big Spring Butte which resulted in the removal of 293 horses. These horses were placed in homes through adoption. The photograph shows the extensive damage to vegetation along the ripar- ian area caused by horses. The second photo was taken one-year later (August 2005) at the same posi- tion and angle, and shows the response of vegetation from reduced grazing pressure of horses. Woody vegetation and other responses of the ecosystem will take many years for restoration from the damage. An additional photograph on the right of the page was taken in September 2002 at Big Spring Creek. The tall vegetation was protected from grazing by the cage on the left side of the photograph. Stubble height of vegetation outside the cage was 4 cm, and 35 cm inside the cage (nearly 10 times the height). The intensity of horse grazing pressure was high until the gather in late 2004. Additional photo com- parisons are available from other riparian sites. Photo credit: FWS, David N. Johnson Department of Interior U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service revised, final Environmental Assessment for Horse and Burro Management at Sheldon National Wildlife Refuge April 2008 Prepared by: U.S. -

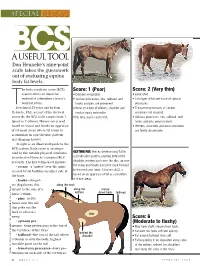

Horses Are Scored Hooks and Pins Are Prominent

SPECIAL REPORT BCS A USEFUL TOOL Don Henneke’s nine-point scale takes the guesswork out of evaluating equine body fat levels. he body condition score (BCS) Score: 1 (Poor) Score: 2 (Very thin) system offers an objective • Extreme emaciation. • Emaciated. method of estimating a horse’s • Spinous processes, ribs, tailhead, and • Thin layer of fat over base of spinous body fat levels. hooks and pins are prominent. processes. TDeveloped 25 years ago by Don • Bone structure of withers, shoulder and • Transverse processes of lumbar Henneke, PhD, as part of his doctoral neck is easily noticeable. vertebrae feel rounded. research, the BCS scale ranges from 1 • No fatty tissue can be felt. • Spinous processes, ribs, tailhead, and (poor) to 9 (obese). Horses are scored hooks and pins are prominent. based on visual and hands-on appraisal • Withers, shoulders and neck structures of six body areas where fat tends to are faintly discernable. accumulate in a predictable pattern (see diagram below). At right is an illustrated guide to the BCS system. Each score is accompa- nied by the notable physical attributes GETTING FAT: Horses develop body fat in described in Henneke’s original BCS a predictable pattern, starting behind the research. The key terms used include: shoulder, moving back over the ribs, up over • crease---a “gutter” over the spine the rump and finally along the back forward created by fat buildup on either side of to the neck and head. A horse’s BCS is the bone. based on an appraisal of fat accumulation • hooks---the pel- in these areas. -

Genetic Diversity and Origin of the Feral Horses in Theodore Roosevelt National Park

RESEARCH ARTICLE Genetic diversity and origin of the feral horses in Theodore Roosevelt National Park Igor V. Ovchinnikov1,2*, Taryn Dahms1, Billie Herauf1, Blake McCann3, Rytis Juras4, Caitlin Castaneda4, E. Gus Cothran4 1 Department of Biology, University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, North Dakota, United States of America, 2 Forensic Science Program, University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, North Dakota, United States of America, 3 Resource Management, Theodore Roosevelt National Park, Medora, North Dakota, United States of America, 4 Department of Veterinary Integrative Biosciences, College of Veterinary Medicine and Bioscience, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas, United States of America a1111111111 a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Feral horses in Theodore Roosevelt National Park (TRNP) represent an iconic era of the North Dakota Badlands. Their uncertain history raises management questions regarding ori- OPEN ACCESS gins, genetic diversity, and long-term genetic viability. Hair samples with follicles were col- lected from 196 horses in the Park and used to sequence the control region of mitochondrial Citation: Ovchinnikov IV, Dahms T, Herauf B, McCann B, Juras R, Castaneda C, et al. (2018) DNA (mtDNA) and to profile 12 autosomal short tandem repeat (STR) markers. Three Genetic diversity and origin of the feral horses in mtDNA haplotypes found in the TRNP horses belonged to haplogroups L and B. The control Theodore Roosevelt National Park. PLoS ONE 13 region variation was low with haplotype diversity of 0.5271, nucleotide diversity of 0.0077 (8): e0200795. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. and mean pairwise difference of 2.93. We sequenced one mitochondrial genome from each pone.0200795 haplotype determined by the control region. -

List of Horse Breeds 1 List of Horse Breeds

List of horse breeds 1 List of horse breeds This page is a list of horse and pony breeds, and also includes terms used to describe types of horse that are not breeds but are commonly mistaken for breeds. While there is no scientifically accepted definition of the term "breed,"[1] a breed is defined generally as having distinct true-breeding characteristics over a number of generations; its members may be called "purebred". In most cases, bloodlines of horse breeds are recorded with a breed registry. However, in horses, the concept is somewhat flexible, as open stud books are created for developing horse breeds that are not yet fully true-breeding. Registries also are considered the authority as to whether a given breed is listed as Light or saddle horse breeds a "horse" or a "pony". There are also a number of "color breed", sport horse, and gaited horse registries for horses with various phenotypes or other traits, which admit any animal fitting a given set of physical characteristics, even if there is little or no evidence of the trait being a true-breeding characteristic. Other recording entities or specialty organizations may recognize horses from multiple breeds, thus, for the purposes of this article, such animals are classified as a "type" rather than a "breed". The breeds and types listed here are those that already have a Wikipedia article. For a more extensive list, see the List of all horse breeds in DAD-IS. Heavy or draft horse breeds For additional information, see horse breed, horse breeding and the individual articles listed below. -

Electronic Supplementary Material - Appendices

1 Electronic Supplementary Material - Appendices 2 Appendix 1. Full breed list, listed alphabetically. Breeds searched (* denotes those identified with inherited disorders) # Breed # Breed # Breed # Breed 1 Ab Abyssinian 31 BF Black Forest 61 Dul Dülmen Pony 91 HP Highland Pony* 2 Ak Akhal Teke 32 Boe Boer 62 DD Dutch Draft 92 Hok Hokkaido 3 Al Albanian 33 Bre Breton* 63 DW Dutch Warmblood 93 Hol Holsteiner* 4 Alt Altai 34 Buc Buckskin 64 EB East Bulgarian 94 Huc Hucul 5 ACD American Cream Draft 35 Bud Budyonny 65 Egy Egyptian 95 HW Hungarian Warmblood 6 ACW American Creme and White 36 By Byelorussian Harness 66 EP Eriskay Pony 96 Ice Icelandic* 7 AWP American Walking Pony 37 Cam Camargue* 67 EN Estonian Native 97 Io Iomud 8 And Andalusian* 38 Camp Campolina 68 ExP Exmoor Pony 98 ID Irish Draught 9 Anv Andravida 39 Can Canadian 69 Fae Faeroes Pony 99 Jin Jinzhou 10 A-K Anglo-Kabarda 40 Car Carthusian 70 Fa Falabella* 100 Jut Jutland 11 Ap Appaloosa* 41 Cas Caspian 71 FP Fell Pony* 101 Kab Kabarda 12 Arp Araappaloosa 42 Cay Cayuse 72 Fin Finnhorse* 102 Kar Karabair 13 A Arabian / Arab* 43 Ch Cheju 73 Fl Fleuve 103 Kara Karabakh 14 Ard Ardennes 44 CC Chilean Corralero 74 Fo Fouta 104 Kaz Kazakh 15 AC Argentine Criollo 45 CP Chincoteague Pony 75 Fr Frederiksborg 105 KPB Kerry Bog Pony 16 Ast Asturian 46 CB Cleveland Bay 76 Fb Freiberger* 106 KM Kiger Mustang 17 AB Australian Brumby 47 Cly Clydesdale* 77 FS French Saddlebred 107 KP Kirdi Pony 18 ASH Australian Stock Horse 48 CN Cob Normand* 78 FT French Trotter 108 KF Kisber Felver 19 Az Azteca -

120-Day Mustang Challenge Faq's

FAQ 120-Day Mustang Challenge 120-DAY MUSTANG CHALLENGE FAQ'S Where did these six mustangs come from? These horses were the offspring of wild horses managed by the Bureau of Land Management. The mothers were captured off of BLM land and taken in by Black Hills Wild Horse Sanctuary. The six geldings were born and raised in North Dakota on the sanctuary. Mary Behrens, in partnership with the Free Rein Foundation, has adopted the Mustangs, transported them to Huntington Beach and will jointly oversee the Mustang Challenge, with the ultimate goal of finding them loving, forever homes. Where does the Mustang come from? American mustangs are descendants of horses brought by the Spanish, beginning in the 16th century. Feral populations became established, especially in the west. These interbred to varying degrees with other breeds, for example, escaped or released ranch horses, racehorses, and other thoroughbreds. Modern populations, therefore, exhibit some variability depending on their ancestry. What are the characteristics of the American Mustang? The physical traits of wild herds can vary quite a bit, and there was a time when characteristics associated with early Spanish strains -- e.g., a short back and deep girth and dun color -- were preferred. Most are small, somewhere between 13 and 15 hands. How do Mustangs live? Mustangs live in large herds. The herd consists of one stallion, around eight females and their young, though separate herds have been known to blend when they are in danger. A female horse, or mare, and a stallion that is over six years of age lead the herd. -

Anatomy of the Dog the Present Volume of Anatomy of the Dog Is Based on the 8Th Edition of the Highly Successful German Text-Atlas of Canine Anatomy

Klaus-Dieter Budras · Patrick H. McCarthy · Wolfgang Fricke · Renate Richter Anatomy of the Dog The present volume of Anatomy of the Dog is based on the 8th edition of the highly successful German text-atlas of canine anatomy. Anatomy of the Dog – Fully illustrated with color line diagrams, including unique three-dimensional cross-sectional anatomy, together with radiographs and ultrasound scans – Includes topographic and surface anatomy – Tabular appendices of relational and functional anatomy “A region with which I was very familiar from a surgical standpoint thus became more comprehensible. […] Showing the clinical rele- vance of anatomy in such a way is a powerful tool for stimulating students’ interest. […] In addition to putting anatomical structures into clinical perspective, the text provides a brief but effective guide to dissection.” vet vet The Veterinary Record “The present book-atlas offers the students clear illustrative mate- rial and at the same time an abbreviated textbook for anatomical study and for clinical coordinated study of applied anatomy. Therefore, it provides students with an excellent working know- ledge and understanding of the anatomy of the dog. Beyond this the illustrated text will help in reviewing and in the preparation for examinations. For the practising veterinarians, the book-atlas remains a current quick source of reference for anatomical infor- mation on the dog at the preclinical, diagnostic, clinical and surgical levels.” Acta Veterinaria Hungarica with Aaron Horowitz and Rolf Berg Budras (ed.) Budras ISBN 978-3-89993-018-4 9 783899 9301 84 Fifth, revised edition Klaus-Dieter Budras · Patrick H. McCarthy · Wolfgang Fricke · Renate Richter Anatomy of the Dog The present volume of Anatomy of the Dog is based on the 8th edition of the highly successful German text-atlas of canine anatomy. -

Mammals of the Nebraska Shortgrass Prairie

Shortgrass Prairie Region Mammal Viewing Tips Mammals can be difficult to see due to their secretive nature. 1. Stay quiet and calm. 2. Be discreet — wear muted clothing and limit fragrances. 3. Look for signs — tracks and scat can tell you if a mammal is in the area, even when you don’t see them. 4. Use binoculars to get a closer look. The shortgrass prairie region includes Always keep a respectful distance Mammals the southwestern corner and Panhandle of from wildlife. Nebraska. This area is made up of short- to 5. Be patient. 6. Go to where the habitat is — visit state mixedgrass prairie and the Pine Ridge. The parks and other public lands. of the shortgrass prairie is the driest and warm- 7. Do your homework — learn what est of the Great Plains grasslands. species of mammals live in the area. This region receives an average of 12 - Nebraska 17 inches of rainfall annually and consists Tracks of buffalo grass and blue grama. The Pine American Badger Ridge is found in northwestern Nebraska Length: 2.5 - 3 in. Shortgrass Width: 2.3 - 2.8 in. and is dominated by ponderosa pine. More Stride: 6 - 12 in. than 300 species of migratory and resident Coyote Prairie birds can be found in the shortgrass prairie Length: 2 - 3.2 in. region, as well as a variety of mammals, Width: 1.4 - 2.4 in. Stride: 8 - 16 in. (walking) plants and other species. Mountain Lion Length: 3 - 4.25 in. Width: 3 - 5 in. Identification Stride: 25 - 45 in. Guide Bobcat Length: 1.8 - 2.5 in. -

The Spanish Mustang and the Long Way Home by Callie Heacock and Ernesto Valdés

The Spanish Mustang and the Long Way Home by Callie Heacock and Ernesto Valdés The evolutionary history and preservation of the Spanish the runner of aboriginal wildness, I had to trace the Age of Horse Mustang is complex; its historical importance to the Spanish- Culture that he brought not only to Western tribes but to white Mexican settlements of Texas and, ultimately, to the colonization men who took their ranges. My chief pleasure has been in telling of the American West, cannot be overstated. J. Frank Dobie, who the tales, legendary as well as factual, of Mustangs and of rides spent years researching The Mustangs and is credited with the on horses of the Mustang breed—but historical business had to best chronicles of the horses ever written, estimated that, at their come before pleasure.”2 The Mustang history in the Americas is height, over a million Mustangs ran free in Texas. In The Mus- believed to begin with the arrival of the first Europeans; how- tangs, he wrote: “To comprehend the stallions that bore conquis- ever, an intriguing twist in its evolutionary path reveals that for tadores across the Americas, I had to go back to mares beside the horses, it was a homecoming. black tents in Arabian deserts. Before I could release myself with In 1493, on Christopher Columbus’ second voyage, twenty 16 Volume 7 • Number 1 • Fall 2009 Spanish horses stepped off the ships onto the Caribbean island to the Americas. As a result, historians cited the arrival of the of Santo Domingo and within a decade, this small band had horse with Columbus as the introduction of a new species into multiplied to over sixty horses. -

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area Jeremy Beaulieu Lisa Andreano Michael Walgren Introduction The following is a guide to the common birds of the Estero Bay Area. Brief descriptions are provided as well as active months and status listings. Photos are primarily courtesy of Greg Smith. Species are arranged by family according to the Sibley Guide to Birds (2000). Gaviidae Red-throated Loon Gavia stellata Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: A small loon seldom seen far from salt water. In the non-breeding season they have a grey face and red throat. They have a long slender dark bill and white speckling on their dark back. Information: These birds are winter residents to the Central Coast. Wintering Red- throated Loons can gather in large numbers in Morro Bay if food is abundant. They are common on salt water of all depths but frequently forage in shallow bays and estuaries rather than far out at sea. Because their legs are located so far back, loons have difficulty walking on land and are rarely found far from water. Most loons must paddle furiously across the surface of the water before becoming airborne, but these small loons can practically spring directly into the air from land, a useful ability on its artic tundra breeding grounds. Pacific Loon Gavia pacifica Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: The Pacific Loon has a shorter neck than the Red-throated Loon. The bill is very straight and the head is very smoothly rounded. -

Wild Horse DNA Report

! ! LEGAL COVENANT FROM THE XENI GWET'IN GOVERNMENT !!!!!!!!!!!!!! in the lands described in , 2013 SC C 44, and their Aboriginal rights to hunt and trap throughout the area claimed in Nation v. British Columbia rights to hunt and trap birds and animals for the purposes of securing animals for work and transportation, food, clothing, shelter, mats, blankets, and crafts, as well as for spiritual, ceremonial, and cultural uses throughout the Brittany T riangle ( This right is inclusive of a right to capture and use horses for transportation and work. The Claim A rea is within the m A rea. Nothing said in our meetings or documents shall abrogate or derogate from Tsilh Del, esqox. ! 2! Characteristic*wild*horse*pocket/wetland*sedge/grassland*habitat*of*the*Brittany*Triangle*Plateau.*This*is*one*of*the*most*remote*and* harsh*wild*horse*areas*left*in*Canada.*This*is*an*unusually*large*group*of*wild*horses,*as*bands*in*the*Brittany*Triangle*usually*number*10@ 14*horses.*Chris*Harris*photo.* * ! 3! Thanks are expressed for financial support from The Vancouver Foundation, Friends of Nemaiah Valley (FONV), Valhalla Wilderness Society (VWS), anonymous donors, and others. Thanks are also extended to the genetics lab at the Department of Veterinary Integrative Bioscience, Texas A&M University, for doing the genetic analysis at nominal costs. research in their Caretaker and Rights Area. Special thanks to Chief Roger William and former Chief Marilyn Baptiste for their ongoing advice and support. BC Parks is thanked for providing research permits for our main sample area, Nunsti Provincial Park. David Williams and Pat Swift of FONV are particularly thanked for their tireless support, enduring faith in the Nemiah People and their horse culture, and for holding so many things together that make things work, as well as for their generosity in providing a comfortable and always interesting research station at Far Meadow.