The Fincastle Resolutions* Lim Glanville

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

X001132127.Pdf

' ' ., ,�- NONIMPORTATION AND THE SEARCH FOR ECONOMIC INDEPENDENCE IN VIRGINIA, 1765-1775 BRUCE ALLAN RAGSDALE Charlottesville, Virginia B.A., University of Virginia, 1974 M.A., University of Virginia, 1980 A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Corcoran Department of History University of Virginia May 1985 © Copyright by Bruce Allan Ragsdale All Rights Reserved May 1985 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: 1 Chapter 1: Trade and Economic Development in Virginia, 1730-1775 13 Chapter 2: The Dilemma of the Great Planters 55 Chapter 3: An Imperial Crisis and the Origins of Commercial Resistance in Virginia 84 Chapter 4: The Nonimportation Association of 1769 and 1770 117 Chapter 5: The Slave Trade and Economic Reform 180 Chapter 6: Commercial Development and the Credit Crisis of 1772 218 Chapter 7: The Revival Of Commercial Resistance 275 Chapter 8: The Continental Association in Virginia 340 Bibliography: 397 Key to Abbreviations used in Endnotes WMQ William and Mary Quarterly VMHB Virginia Magazine of History and Biography Hening William Waller Hening, ed., The Statutes at Large; Being� Collection of all the Laws Qf Virginia, from the First Session of the Legislature in the year 1619, 13 vols. Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia Rev. Va. Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence, 7 vols. LC Library of Congress PRO Public Record Office, London co Colonial Office UVA Manuscripts Department, Alderman Library, University of Virginia VHS Virginia Historical Society VSL Virginia State Library Introduction Three times in the decade before the Revolution. Vir ginians organized nonimportation associations as a protest against specific legislation from the British Parliament. -

Leedstown.Lwp

Leedstown and Fincastle Jim Glanville Copyright 2010 All rights reserved Blue links in the footnotes are clickable The Winter 2010 Newsletter of the Northern Neck of Virginia Historical Society announced a February 27th, 2010 reenactment of the 243rd anniversary of the Leedstown Resolutions1 saying: "History will come to life along the streets of Tappahannock as NNVHS and the Essex County Museum and Historical Society combine to present dramatic reenactments of the famous 1766 Tappahannock Demonstrations to enforce the Leedstown Resolutions, against the wealthy and insolent Archibald Ritchie2 and the Scotsman Stamp Collector, Archibald McCall, who was tarred and feathered for his refusal to comply." Because I am interested in, and have written about, the pre-revolutionary-period Virginia County Resolutions I decided to attend. This article tells about the 1766 Leedstown Resolutions (adopted in Westmoreland County) and their February 2010 reenactment in Tappahannock. It also tells about the role of Richard Henry Lee during the buildup to revolution in Virginia and explores the connections between Westmoreland County and Fincastle County, which existed briefly from 1772-1776. Reenacting an event of 244 years earlier, Richard Henry Lee Richard Henry Lee confronts Archibald McCall (portrayed (portrayed by Ted Borek) acting on behalf of the Westmoreland by Dan McMahon) and his wife (portrayed by Judith Association confronts Archibald Ritchie (portrayed by Bob Bailey) Harris) on the steps of the extensively restored at Ritchie's front door in Tappahannock. Samuel Washington Brockenbrough-McCall House4 that is today a part of (portrayed by John Harris) stands with a cane. Bailey as Ritchie present day St. -

October 2015 E-Newsletter in This Issue Postponements Let's Visit James Monroe!

VISITING EXHIBITS & PROGRAMS NEWS RENTALS GIVING ABOUT THE MUSEUM COLLECTIONS October 2015 E-Newsletter In This Issue Postponements Let's Visit James Monroe! Bowley Projects Postponements What's In Store? Our two events for the weekend of October 2-4 Upcoming Events have been postponed due to weather concerns: Quick Links Our website History Trivia Night - We are planning to shift our final First Friday History Trivia Newsletter Night of 2015 to the first Friday in November (the 6th). The Archive location is TBD. Keep an eye out for future updates. Become a "Music for Mr. Monroe" - A Concert of Colonial Friend of JMM! Music - Our concert featuring David and Ginger Hildebrand of The Find us on Colonial Music Institute has been rescheduled for Sunday, Social Media: December 6th, at 2:00 pm in Monroe Hall room 116. Let's Visit James Monroe! Don't miss next month's newsletter where we will announce a release date for the James Monroe Museum's new children's book, Let's Visit James Monroe! We look forward to sharing the life and legacy of James Monroe with generations of readers to come, through this lively story of history coming to life during a Upcoming family's visit to the Museum. Events Keep an eye out for details on the book release party featuring Fri., November 6: author and illustrator Julia Livi! First Friday History Trivia Spotlight: Bowley Scholar Projects Night with Quizmaster Gaye Adegbalola. The Bowley Scholars are undertaking Trivia, cash bar, several exciting projects this month. In light refreshments, addition to inventory and archive & 50/50 raffle. -

Abbot, John, 430 Abernethy, Thomas P., and Yorke-Camden Opinion

INDEX Abbot, John, 430 Alger, Orestes (Uncle Ret), 405 Abernethy, Thomas P., and Yorke-Camden Alger, Roger (J. 1812), 368 opinion (i773>> 47~48 Alger, Roger, 406 Abolition, as controversial factor (1830- Alger. Walter, 370 1845), rev«> 47^. See also Antislavery move- Allegheny College: literary societies, 272^273, ment 274; student life in (19th century),f20a, Acade*mie Royale des Sciences, 53, 55, 56 266, 267; student pledge, to observe|laws Academy of Philadelphia. See University of of, 256 Pennsylvania Allegheny County, 443 Acrobats, Japanese, 396, 398 Allen, Carlos R., Jr., rev. of Wilmerding's Adams, Charles Francis, biog. of, rev., 473- James Monroe, Public Claimant, 228-229 474 Allen, Paul, 1777* Adams, John, 22, 25; letters intercepted Allen, William, 41 gn (1775), 21 Alvord, Clarence W., 42, 45 Adams, John Quincy (1833-1894), 445 The American Historian. A Social-Intellectual Adelman, Seymour, rev. of American Literary History of the Writing of the American Past, Manuscripts . , 333*334 by Wish, rev., 463-465 Admiralty courts, 34; and Am. Rev., rev., American Hotel, Phila., 207 89-90 American House, 419W After the Civil War. A Pictorial Profile of American Immigration, by Jones, rev., 251- America from 1865 to I goo, by Blay, rev., 252 484 American Indians, by Hagan, rev., 468-470 Agassiz, Louis, biog. of, rev., 475-476 American Literary Manuscripts. A Checklist of Agriculture: decline in rural workers (1860's), Holdings in Academic, Historical and Public 440; equipment used for, 371-410 passim; Libraries in the United States, rev., 333-334 farm life, in Pa. (1890's), 367-410; study of, American Mercury, Hartford, Conn, news- in U. -

William Preston and the Revolutionary Settlement

Journal of Backcountry Studies EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the third and last installment of the author’s 1990 University of Maryland dissertation, directed by Professor Emory Evans, to be republished in JBS. Dr. Osborn is President of Pacific Union College. William Preston and the Revolutionary Settlement BY RICHARD OSBORN Patriot (1775-1778) Revolutions ultimately conclude with a large scale resolution in the major political, social, and economic issues raised by the upheaval. During the final two years of the American Revolution, William Preston struggled to anticipate and participate in the emerging American regime. For Preston, the American Revolution involved two challenges--Indians and Loyalists. The outcome of his struggles with both groups would help determine the results of the Revolution in Virginia. If Preston could keep the various Indian tribes subdued with minimal help from the rest of Virginia, then more Virginians would be free to join the American armies fighting the English. But if he was unsuccessful, Virginia would have to divert resources and manpower away from the broader colonial effort to its own protection. The other challenge represented an internal one. A large number of Loyalist neighbors continually tested Preston's abilities to forge a unified government on the frontier which could, in turn, challenge the Indians effectivel y and the British, if they brought the war to Virginia. In these struggles, he even had to prove he was a Patriot. Preston clearly placed his allegiance with the revolutionary movement when he joined with other freeholders from Fincastle County on January 20, 1775 to organize their local county committee in response to requests by the Continental Congress that such committees be established. -

William Campbell of King's Mountain David George Malgee

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 8-1983 A Frontier Biography: William Campbell of King's Mountain David George Malgee Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Malgee, David George, "A Frontier Biography: William Campbell of King's Mountain" (1983). Master's Theses. 1296. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses/1296 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Frontier Biography: William Campbell of King's Mountain by David George Malgee A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Richmond In Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in History August, 1983 A Frontier Biography: William Campbell of King's Mountain Thesis Submitted to the Department of History of the Graduate School of the University of Richmond by David George Malgee Approved: Introduction . l Chapter I: The Early Years ........................................ 3 Chapter II: Captain Campbell ...................................... 22 Chapter III: The Outbreak of the American Revolution .............. 39 Chapter IV: The Quiet Years, 1777 - 1778 .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 56 Chapter V: The Critical Months, April 1779 - June 1780 ............ 75 Chapter VI: Prelude to Fame . 97 Chapter VII: William Campbell of King's Mountain .................. 119 Chapter VIII: Between Campaigns, November - December 1780 ......... 179 Chapter IX: The Guilford Courthouse Campaign ...................... 196 Chapter X: General William Campbell, April - August 1781 ......... -

Link.Net Chancellor General Davis Lee Wright, Esq., P.O

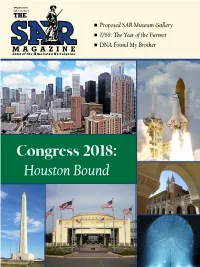

SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 n Proposed SAR Museum Gallery n 1768: The Year of the Farmer n DNA Found My Brother Congress 2018: Houston Bound SPRING 2018 Vol. 112, No. 4 6 16 6 2018 Congress to Convene 10 America’s Heritage and the 22 Newly Acquired Letters in Houston SAR Library Reveal More About the Maryland 400 7 Amendment Proposal/ 11 The Proposed SAR Museum Leadership Medical Committee Gallery 24 State Society & Chapter News 8 Nominating Committee Report/Butler Awarded 16 250th Series: 1768—The Year 38 In Our Memory/ Medal of Honor of the Farmer New Members 9 Newsletter Competitions 20 DNA Found My Brother 47 When You Are Traveling THE SAR MAGAZINE (ISSN 0161-0511) is published quarterly (February, May, August, November) and copyrighted by the National Society of the Sons of the American Revolution, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. Periodicals postage paid at Louisville, KY and additional mailing offices. Membership dues include The SAR Magazine. Subscription rate $10 for four consecutive issues. Single copies $3 with checks payable to “Treasurer General, NSSAR” mailed to the HQ in Louisville. Products and services advertised do not carry NSSAR endorsement. The National Society reserves the right to reject content of any copy. Send all news matter to Editor; send the following to NSSAR Headquarters: address changes, election of officers, new members, member deaths. Postmaster: Send address changes to The SAR Magazine, 809 West Main Street, Louisville, KY 40202. PUBLISHER: STAFF DIRECTORY President General Larry T. Guzy As indicated below, staff members have an email address and an extension number of the automated 4531 Paper Mill Road, SE telephone system to simplify reaching them. -

Charles H. Coleman Collection CONTAINER LIST EIU University Archives Booth Library

Charles H. Coleman Collection CONTAINER LIST EIU University Archives Booth Library Box 1: U.S. History Folders: 1—New France to 1748—1930-31 2—French and Indian Wars—1749-1764 3—U.S. History Bibliography—1924-1938 4—Pre-Columbian Indians Misc.—1926-1940 5—Pre-Columbian Norse—1932-1949 6—Discovery and Exploration—1926-1954 7—Colonial Architecture 8—Colonial Education and Publications—1929-30 9—Colonial Society—1925-1940 10—Quarrel with England—1753-1775—1921-1941 11—Constitutional Movement—1754-1739—1936-1953 12—Constitutional Amendments—1927-1954 13—Outbreak of the Revolution—1775-1776—1925-1956 15—Revolution through Burgoyne'a surrender—1922-1951 16—The Navy in the Revolution--1524-1951 17—Revolution—Foreign Aid—1925-1934 18—Revolution—Saratoga to Yorktown--1926-1934 19—Revolution—Conquest for the Northwest—1929 20—Peace Treaty—1782-1783—1930-31 21—The U.S. under the Articles of Confederation—1926-1936 22—The State of Franklin, 1784—1930-32 23—The Northwest Territory—1939 24—Federal Constitution—General—1926-1938 25—Social Development, 1789-1820—1927-1939 26—Washington's Administration—1930-39 27—John Adam's Administration—1931 28—Jefferson's Administration—1927-1942 29—Spanish-American Revolt—1926-1930 30—Louisiana Purchase—1926-1953 31—Quarrel with England and France—1935 32—The War of 1812—1926-1956 33—The War of 1812—Navy—1931-38 34—Administration of John Quincy Adams—1929-1931 35—Bailey's The American Pageant Map 36—Western Development, 1320-1360—1929-1933 37—Social and Economic Movements, 1820-1860—1931-1945 38—Educational & Humanitarian Development—1820-1860—1929-31 39—Monroe's Administration—1921-1949 40—The Monroe Doctrine—1928-1943 41—National Nominating Conventions—1932 42—Jackson's First Administration—1931-34 43— Jackson’s Second Administration—1929-1959 44—The Texas Revolution—1929-1949 45—Political Chronology—1845-1377 46—Thomas A. -

Blueprint Virginia

BLUEPRINT VIRGINIA A Business Plan for the Commonwealth Dear Community and Business Leaders: NOVEMBER 20, 2013 In Virginia, we’ve long been blessed by a strong economy and have regularly been recognized as the best state for business. While we have much to be thankful for, there are still issues that need further consideration as we continue to compete in an increasingly global economy. There are areas of the Commonwealth that are not enjoying the level of prosperity experienced by others. We must remain vigilant in our efforts to foster statewide economic development in order to maintain our ranking as the best state for business. We are pleased to share with you the executive summary for Blueprint Virginia: A Business Plan for the Commonwealth. Blueprint Virginia is a comprehensive initiative to provide business leadership, direction and long-range economic development planning for Virginia. During the past twelve months, the Blueprint process engaged business and community leaders from around the state through grassroots involvement to determine top priorities for strengthening Virginia’s economic competitiveness. Regional briefings were held in more than 30 communities where hundreds of Virginia citizens voted on priority issues for their region and the state. We collaborated with more than 300 organizations and over 7,000 participants to develop “A Business Plan for the Commonwealth” that provides our elected officials and private sector leaders with a roadmap for economic competitiveness. We would like to express our deep gratitude to the many organizations and individuals who contributed their leadership, insights and support to Blueprint Virginia. It has been our honor to provide leadership throughout the Blueprint Virginia planning process. -

Event Rental Information Packet Weddings, Bridal Showers, Baby Showers, Birthday Parties, Anniversary Parties, & More!

American Women’s Heritage Society, Inc. Historic Belmont Mansion & Underground Railroad Museum West Fairmount Park, Philadelphia, PA 19131 Call 215-878-8844 – Fax 215-878-9439 Www.belmontmansion.org [email protected] Host your Wedding & Events at The Historic Belmont Mansion & Underground Railroad Museum The Crown Jewel of Fairmount Park Event Rental Information Packet Weddings, bridal showers, baby showers, birthday parties, anniversary parties, & more! American Women’s Heritage Society, Inc. Historic Belmont Mansion & Underground Railroad Museum West Fairmount Park, Philadelphia, PA 19131 Call 215-878-8844 – Fax 215-878-9439 Www.belmontmansion.org [email protected] History of The Belmont Mansion Belmont Mansion, the 18th, 19th Century home of the Peters’ family provides the setting for telling the story of the Fairmount Park area of Philadelphia from colonization to the present. Initially a group of farms, the property was bought in 1742 by William Peters, an upper-class English lawyer who served as a land management agent for the Penn family. Peters designed and built Belmont Mansion, the finest example of Palladian architecture in America, and created extensive formal gardens surrounding the Mansion. With the coming of the American Revolution, Belmont Mansion passed to William’s son, Richard Peters, who served as the Secretary of War for the Revolutionary Army, Pennsylvania Delegate to Congress under the articles of the Confederation, Speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly, Pennsylvania State Senator, and Judge of the United States District Court of Pennsylvania. During his residence, Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Madison, Lafayette, and other “Founding Fathers” visited Belmont Mansion. As an early environmental scientist, Judge Peters converted the Belmont Estate into a working model farm to promote scientific agriculture. -

History of the Virginia Teachers Association, 1940-1965

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1981 History of the Virginia Teachers Association, 1940-1965 Alfred Kenneth Talbot Jr. College of William & Mary - School of Education Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Other Education Commons Recommended Citation Talbot, Alfred Kenneth Jr., "History of the Virginia Teachers Association, 1940-1965" (1981). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539618582. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.25774/w4-v941-v858 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

"The Rebellion's Rebellious Little Brother" : the Martial, Diplomatic

“THE REBELLION’S REBELLIOUS LITTLE BROTHER”: THE MARTIAL, DIPLOMATIC, POLITICAL, AND PERSONAL STRUGGLES OF JOHN SEVIER, FIRST GOVERNOR OF TENNESSEE A thesis presented to the faculty of the Graduate School of Western Carolina University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in History. By Meghan Nichole Essington Director: Dr. Honor Sachs Assistant Professor of History History Department Committee Members: Dr. Andrew Denson, History Dr. Alex Macaulay, History April 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people who have helped me in making this thesis a reality. It is impossible to name every individual who impacted the successful completion of this study. I must mention Dr. Kurt Piehler, who sparked my interest in Tennessee’s first governor during my last year of undergraduate study at the University of Tennessee. Dr. Piehler encouraged me to research what historians have written about John Sevier. What I found was a man whose history had largely been ignored and forgotten. Without this initial inquiry, it is likely that I would have picked a very different topic to study. I am greatly indebted to Dr. Piehler. While an undergraduate in the history program at UTK I met a number of exceptional historians who inspired and encouraged me to go to graduate school. Dr. Bob Hutton, Dr. Stephen Ash, and Dr. Nancy Schurr taught me to work harder, write better, and never give up on my dream. They have remained mentors to me throughout my graduate career, and their professional support and friendship is precious to me. Also, while at UTK, I met a number of people who have continued to be influential and incredible friends.