Distribution, Abundance, and Habitat Associations of Franklin's Ground Squirrel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Indian Chief, an English Tourist, a Doctor, a Reverend, and a Member of Ppparliament: the Journeys of Pasqua’S’S’S Pictographs and the Meaning of Treaty Four

The Journeys of Pasqua’s Pictographs 109 AN INDIAN CHIEF, AN ENGLISH TOURIST, A DOCTOR, A REVEREND, AND A MEMBER OF PPPARLIAMENT: THE JOURNEYS OF PASQUA’S’S’S PICTOGRAPHS AND THE MEANING OF TREATY FOUR Bob Beal 7204 76 Street Edmonton, Alberta Canada, T6C 2J5 [email protected] Abstract / Résumé Indian treaties of western Canada are contentious among historians, First Nations, governments, and courts. The contemporary written docu- mentation about them has come from one side of the treaty process. Historians add information from such disciplines as First Nations Tradi- tional Knowledge and Oral History to draw as complete a picture as possible. Now, we have an additional source of written contemporary information, Chief Pasqua’s recently rediscovered pictographs showing the nature of Treaty Four and its initial implementation. Pasqua’s ac- count, as contextualized here, adds significantly to our knowledge of the western numbered treaty process. The pictographs give voice to Chief Pasqua’s knowledge. Les traités conclus avec les Indiens de l’Ouest canadien demeurent liti- gieux pour les historiens, les Premières nations, les gouvernements et les tribunaux. Les documents contemporains qui discutent des traités ne proviennent que d’une seule vision du processus des traités. Les historiens ajoutent des renseignements provenant de disciplines telles que les connaissances traditionnelles et l’histoire orale des Autochto- nes. Ils bénéficient désormais d’une nouvelle source écrite contempo- raine, les pictogrammes récemment redécouverts du chef Pasqua, qui illustrent la nature du Traité n° 4 et les débuts de son application. Le compte rendu du chef, tel que replacé dans son contexte, est un ajout important à notre connaissance du processus des traités numérotés dans l’Ouest canadien. -

Lt. Aemilius Simpson's Survey from York Factory to Fort Vancouver, 1826

The Journal of the Hakluyt Society August 2014 Lt. Aemilius Simpson’s Survey from York Factory to Fort Vancouver, 1826 Edited by William Barr1 and Larry Green CONTENTS PREFACE The journal 2 Editorial practices 3 INTRODUCTION The man, the project, its background and its implementation 4 JOURNAL OF A VOYAGE ACROSS THE CONTINENT OF NORTH AMERICA IN 1826 York Factory to Norway House 11 Norway House to Carlton House 19 Carlton House to Fort Edmonton 27 Fort Edmonton to Boat Encampment, Columbia River 42 Boat Encampment to Fort Vancouver 62 AFTERWORD Aemilius Simpson and the Northwest coast 1826–1831 81 APPENDIX I Biographical sketches 90 APPENDIX II Table of distances in statute miles from York Factory 100 BIBLIOGRAPHY 101 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Fig. 1. George Simpson, 1857 3 Fig. 2. York Factory 1853 4 Fig. 3. Artist’s impression of George Simpson, approaching a post in his personal North canoe 5 Fig. 4. Fort Vancouver ca.1854 78 LIST OF MAPS Map 1. York Factory to the Forks of the Saskatchewan River 7 Map 2. Carlton House to Boat Encampment 27 Map 3. Jasper to Fort Vancouver 65 1 Senior Research Associate, Arctic Institute of North America, University of Calgary, Calgary AB T2N 1N4 Canada. 2 PREFACE The Journal The journal presented here2 is transcribed from the original manuscript written in Aemilius Simpson’s hand. It is fifty folios in length in a bound volume of ninety folios, the final forty folios being blank. Each page measures 12.8 inches by seven inches and is lined with thirty- five faint, horizontal blue-grey lines. -

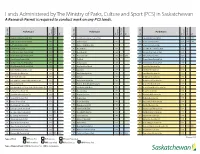

In Saskatchewan

Lands Administered by The Ministry of Parks, Culture and Sport (PCS) in Saskatchewan A Research Permit is required to conduct work on any PCS lands. Park Name Park Name Park Name Type of Park Type Year Designated Amendment Year of Park Type Year Designated Amendment Year of Park Type Year Designated Amendment Year HP Cannington Manor Provincial Park 1986 NE Saskatchewan Landing Provincial Park 1973 RP Crooked Lake Provincial Park 1986 PAA 2018 HP Cumberland House Provincial Park 1986 PR Anderson Island 1975 RP Danielson Provincial Park 1971 PAA 2018 HP Fort Carlton Provincial Park 1986 PR Bakken - Wright Bison Drive 1974 RP Echo Valley Provincial Park 1960 HP Fort Pitt Provincial Park 1986 PR Besant Midden 1974 RP Great Blue Heron Provincial Park 2013 HP Last Mountain House Provincial Park 1986 PR Brockelbank Hill 1992 RP Katepwa Point Provincial Park 1931 HP St. Victor Petroglyphs Provincial Park 1986 PR Christopher Lake 2000 PAA 2018 RP Pike Lake Provincial Park 1960 HP Steele Narrows Provincial Park 1986 PR Fort Black 1974 RP Rowan’s Ravine Provincial Park 1960 HP Touchwood Hills Post Provincial Park 1986 PR Fort Livingstone 1986 RP The Battlefords Provincial Park 1960 HP Wood Mountain Post Provincial Park 1986 PR Glen Ewen Burial Mound 1974 RS Amisk Lake Recreation Site 1986 HS Buffalo Rubbing Stone Historic Site 1986 PR Grasslands 1994 RS Arm River Recreation Site 1966 HS Chimney Coulee Historic Site 1986 PR Gray Archaeological Site 1986 RS Armit River Recreation Site 1986 HS Fort Pelly #1 Historic Site 1986 PR Gull Lake 1974 RS Beatty -

The Biological Resources of Illinois Caves and Other

I LLINOI S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. EioD THE BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES OF ILLINOIS CAVES AND OTHER SUBTERRANEAN ENVIRONMENTS Determination of the Diversity, Distribution, and Status of the Subterranean Faunas of Illinois Caves and How These Faunas are Related to Groundwater Quality Donald W. Webb, Steven J. Taylor, and Jean K. Krejca Center for Biodiversity Illinois Natural History Survey 607 East Peabody Drive Champaign, Illinois 61820 (217) 333-6846 TECHNICAL REPORT 1993 (8) ILLINOIS NATURAL HISTORY SURVEY CENTER FOR BIODIVERSITY Prepared for: The Environmental Protection Trust Fund Commission and Illinois Department of Energy and Natural Resources Office of Research and Planning 325 W. Adams, Room 300 Springfield, IL 62704-1892 Jim Edgar, Governor John Moore, Director State of Illinois Illinois Department of Energy and Natural Resources ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Funding for this project was provided through Grant EPTF23 from the Environmental Protection Trust Fund Commission, administered by the Department of Energy and Natural Resources (ENR). Our thanks to Doug Wagner and Harry Hendrickson (ENR) for their assistance. Other agencies that contributed financial support include the Shawnee National Forest (SNF) and the Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT). Many thanks to Mike Spanel (SNF) and Rich Nowack (IDOT) for their assistance. Several agencies cooperated in other ways; we are. grateful to: Illinois Department of Conservation (IDOC); Joan Bade of the Monroe-Randolph Bi- County Health Department; Russell Graham and Jim Oliver, Illinois State Museum (ISM); Dr. J. E. McPherson, Zoology Department, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale (SIUC). Further contributions were made by the National Speleological Society, Little Egypt and Mark Twain Grottoes of the National Speleological Society, and the Missouri Speleological Survey. -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

Robert Ridgway 1850-1929

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIRS VOLUME XV SECOND MEMOIR BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF ROBERT RIDGWAY 1850-1929 BY ALEXANDER WETMORE PRESENTED TO THE ACADEMY AT THE ANNUAL MEETING, 1931 ROBERT RIDGWAY 1850-1929 BY ALEXANDER WETMORE Robert Ridgway, member of the National Academy of Science, for many years Curator of Birds in the United States National Museum, was born at Mount Carmel, Illinois, on July 2, 1850. His death came on March 25, 1929, at his home in Olney, Illinois.1 The ancestry of Robert Ridgway traces back to Richard Ridg- way of Wallingford, Berkshire, England, who with his family came to America in January, 1679, as a member of William Penn's Colony, to locate at Burlington, New Jersey. In a short time he removed to Crewcorne, Falls Township, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, where he engaged in farming and cattle raising. David Ridgway, father of Robert, was born March 11, 1819, in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. During his infancy his family re- moved for a time to Mansfield, Ohio, later, about 1840, settling near Mount Carmel, Illinois, then considered the rising city of the west through its prominence as a shipping center on the Wabash River. Little is known of the maternal ancestry of Robert Ridgway except that his mother's family emigrated from New Jersey to Mansfield, Ohio, where Robert's mother, Henrietta James Reed, was born in 1833, and then removed in 1838 to Calhoun Praifle, Wabash County, Illinois. Here David Ridgway was married on August 30, 1849. Robert Ridgway was the eldest of ten children. -

Outdoor Adventures

Outdoor Adventures Destination Guide (North Dakota, South Dakota, and Minnesota) 1 Outdoor Adventures – Greater Grand Forks The Greenway Website www.greenwayggf.com Phone 701-738-8746 Location Grand Forks, North Dakota and East Grand Forks, Minnesota Distance from Grand Forks Inside City Limits Map http://www.greenwayggf.com/greenway/Attachments%20&%20links/Maps/FinalGreenwayMap _April2012.pdf Grand Forks’ Parks and Facilities Website www.gfparks.org/parksfacilities.htm Phone 701-973-2711 Location Grand Forks, North Dakota Distance from Grand Forks Inside City Limits 2 East Grand Forks’ Parks and Recreation Website www.egf.mn/index.aspx?NID=210 Phone 218-773-8000 Location East Grand Forks, Minnesota Distance from Grand Forks Across the Red River 3 Outdoor Adventures – North Dakota Turtle River State Park Website www.parkrec.nd.gov/parks/trsp/trsp.html Phone 701-594-4445 Location Arvilla, North Dakota Activities Camping, Hiking, Mountain Biking, Cross Country Skiing, Fishing, Snowshoeing, and Sledding Distance from Grand Forks 22 Miles (27 Minutes) Directions and Map http://goo.gl/maps/R9Me0 Larimore Dam Recreation Area Website www.gfcounty.nd.gov/?q=node/51 Phone 701-343-2078 Location Larimore, North Dakota Activities Camping, Biking, Fishing, and Boating Distance from Grand Forks 28 Miles (34 Minutes) Directions and Map http://goo.gl/maps/npvR0 4 Grahams Island State Park Website www.parkrec.nd.gov/parks/gisp/gisp.html Phone 701-766-4015 Location Devils Lake, North Dakota Activities Camping, Boating, Fishing, Cross Country Skiing, and -

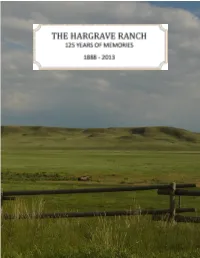

Memoir-Sneak-Peek-For-Website1.Pdf

The Hargrave Ranch: Five Generations of Change (1888 – 2013) 1 Lorna Michael Butler2 3 The story of the Hargrave Ranch, Walsh, Alberta, as portrayed in 2013, blends the backgrounds and contributions of five unique generations. While this synopsis cannot begin to do justice to the contributions and experiences of each generation, it is an attempt to paint a brief picture of the roles that each generation played in shaping the Hargrave Ranch over 125 years. In retrospect, there have been many key individuals, both women and men, who have played important roles, and not all were family members. It is apparent that it takes a dedicated team to develop and operate a southern Alberta cattle ranch for 125 years. Each generation has made unique contributions, and has faced challenges that could not have been predicted. But the JH ranch and the natural resources that are key to its resilience have been husbanded in keeping with the best knowledge and technology that was available at the time. Five generation of Hargraves, and their families, neighbors and friends must be credited with making the JH Ranch the special place that it is today. The story that follows is intended to highlight the ranching business itself, however, the story cannot be told without glimpses of the lives of the people who have been involved. 1. The Founding Family and First Generation: James (‘Jimmy’) Hargrave and Alexandra “Lexie’ Helen Sissons The Ancestors of James Hargrave James Hargrave (1846-1935) was born in Beech Ridge (one source refers to his birthplace as Chataugee), Quebec (50 mi. -

Shopping in the Late Nineteenth Century: the Hudson’S Bay Company and Its Transition from the Fur Trade to Retailing

SHOPPING IN THE LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY: THE HUDSON’S BAY COMPANY AND ITS TRANSITION FROM THE FUR TRADE TO RETAILING A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts In the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Jennifer Anne Schmidt ©Jennifer Schmidt, December, 2011. All rights reserved. Permission to Use In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying, publication, or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Archaeology and Anthropology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5B1 Canada i Abstract The South Battleford Project began in 1972 with salvage excavations in the historic town of Battleford, Saskatchewan. -

The Hoosier- Shawnee Ecological Assessment Area

United States Department of Agriculture The Hoosier- Forest Service Shawnee Ecological North Central Assessment Research Station General Frank R. Thompson, III, Editor Technical Report NC-244 Thompson, Frank R., III, ed 2004. The Hoosier-Shawnee Ecological Assessment. Gen. Tech. Rep. NC-244. St. Paul, MN: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, North Central Research Station. 267 p. This report is a scientific assessment of the characteristic composition, structure, and processes of ecosystems in the southern one-third of Illinois and Indiana and a small part of western Kentucky. It includes chapters on ecological sections and soils, water resources, forest, plants and communities, aquatic animals, terrestrial animals, forest diseases and pests, and exotic animals. The information presented provides a context for land and resource management planning on the Hoosier and Shawnee National Forests. ––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Key Words: crayfish, current conditions, communities, exotics, fish, forests, Hoosier National Forest, mussels, plants, Shawnee National Forest, soils, water resources, wildlife. Cover photograph: Camel Rock in Garden of the Gods Recreation Area, with Shawnee Hills and Garden of the Gods Wilderness in the back- ground, Shawnee National Forest, Illinois. Contents Preface....................................................................................................................... II North Central Research Station USDA Forest Service Acknowledgments ................................................................................................... -

Declaration of Fort Carlton 2007

DECLARATION OF FORT CARLTON TREATIES NO. 1 -11 GATHERING JULY 22 – 27, 2007 WHEREAS the Indigenous Nations from the Treaty Territories of Treaties No. 1 - 11 have gathered in assembly in the ancestral territories of the Willow Cree at Fort Carlton, Saskatchewan on July 22 – 27, 2007 to discuss the importance of the Treaties for the benefit of all of our future generations and the protection of Mother Earth; and WHEREAS by virtue of their very existence, Indigenous Nations of Treaties No. 1 - 11 have the right to live freely in their own territories and their close relationship with Mother Earth and the spiritual realm must be recognized and understood as the basis for their cultures, spiritual life, cultural integrity and economic survival. For the Indigenous Nations of Treaties No. 1 - 11; relationship with the land is not simply one of possession and production, it is also a material and spiritual element that they should be able to enjoy freely, as well as a means of preserving their cultural heritage and transmitting it to future generations; and WHEREAS through the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples the United Nations Human Rights Council has recognized the collective rights of Indigenous Peoples. The Committee on Human Rights, monitoring agent for the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, applies the right to self determination as a right of the Indigenous Peoples of Canada and to other States as a legal obligation of the State. This same Committee on Human Rights has also recognized, in its General -

South Dakota Boating Laws and Responsibilities

the the OF SOUTH DAKOTA BOATING LAWS AND RESPONSIBILITIES 2015 Edition Copyright © 2015 Boat Ed, www.boat-ed.com Department of Game, Fish & Parks The purpose of the Department of Game, Fish & Parks is to perpetuate, conserve, manage, protect, and enhance South Dakota’s wildlife resources, parks, and outdoor recre- ational opportunities for the use, benefit, and enjoyment of the people of this state and its visitors, and to give the highest priority to the welfare of this state’s wildlife and parks, and their environment, in planning and decisions. DIVISION OF WILDLIFE manages South Dakota’s wildlife and fisheries resources and their associ- ated habitats for their sustained and equitable use, and for the benefit, welfare, and enjoyment of the citizens of this state and its visitors. 605-223-7660 DIVISION OF PARKS AND RECREATION is committed to providing diverse outdoor recreational opportunities, acting as a catalyst for a growing tourism economy, and preserving the resources with which we are entrusted. We will accomplish this through efficient, responsive, and environmentally sensitive management and constructive communication with those we serve. 605-773-3391 South Dakota Game, Fish & Parks 523 East Capitol Avenue Pierre, SD 57501 www.gfp.sd.gov Copyright © 2015 Boat Ed, www.boat-ed.com the the OF SOUTH DAKOTA BOATING LAWS AND RESPONSIBILITIES Published by Boat Ed, a division of Kalkomey Enterprises, Inc., 14086 Proton Road, Dallas, TX 75244, 214-351-0461. Printed in the U.S.A. Copyright © 2005–2015 by Kalkomey Enterprises, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any process without permission in writing from Kalkomey Enterprises, Inc.