Modernism on Trial: an Analysis of Historic Preservation Debates in Chicago Stephen M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brief History of Architecture in N.C. Courthouses

MONUMENTS TO DEMOCRACY Architecture Styles in North Carolina Courthouses By Ava Barlow The judicial system, as one of three branches of government, is one of the main foundations of democracy. North Carolina’s earliest courthouses, none of which survived, were simple, small, frame or log structures. Ancillary buildings, such as a jail, clerk’s offi ce, and sheriff’s offi ce were built around them. As our nation developed, however, leaders gave careful consideration to the structures that would house important institutions – how they were to be designed and built, what symbols were to be used, and what building materials were to be used. Over time, fashion and design trends have changed, but ideals have remained. To refl ect those ideals, certain styles, symbols, and motifs have appeared and reappeared in the architecture of our government buildings, especially courthouses. This article attempts to explain the history behind the making of these landmarks in communities around the state. Georgian Federal Greek Revival Victorian Neo-Classical Pre – Independence 1780s – 1820 1820s – 1860s 1870s – 1905 Revival 1880s – 1930 Colonial Revival Art Deco Modernist Eco-Sustainable 1930 - 1950 1920 – 1950 1950s – 2000 2000 – present he development of architectural styles in North Carolina leaders and merchants would seek to have their towns chosen as a courthouses and our nation’s public buildings in general county seat to increase the prosperity, commerce, and recognition, and Trefl ects the development of our culture and history. The trends would sometimes donate money or land to build the courthouse. in architecture refl ect trends in art and the statements those trends make about us as a people. -

YALE ARCHITECTURE FALL 2011 Constructs Yale Architecture

1 CONSTRUCTS YALE ARCHITECTURE FALL 2011 Constructs Yale Architecture Fall 2011 Contents “Permanent Change” symposium review by Brennan Buck 2 David Chipperfield in Conversation Anne Tyng: Inhabiting Geometry 4 Grafton Architecture: Shelley McNamara exhibition review by Alicia Imperiale and Yvonne Farrell in Conversation New Users Group at Yale by David 6 Agents of Change: Geoff Shearcroft and Sadighian and Daniel Bozhkov Daisy Froud in Conversation Machu Picchu Artifacts 7 Kevin Roche: Architecture as 18 Book Reviews: Environment exhibition review by No More Play review by Andrew Lyon Nicholas Adams Architecture in Uniform review by 8 “Thinking Big” symposium review by Jennifer Leung Jacob Reidel Neo-avant-garde and Postmodern 10 “Middle Ground/Middle East: Religious review by Enrique Ramirez Sites in Urban Contexts” symposium Pride in Modesty review by Britt Eversole review by Erene Rafik Morcos 20 Spring 2011 Lectures 11 Commentaries by Karla Britton and 22 Spring 2011 Advanced Studios Michael J. Crosbie 23 Yale School of Architecture Books 12 Yale’s MED Symposium and Fab Lab 24 Faculty News 13 Fall 2011 Exhibitions: Yale Urban Ecology and Design Lab Ceci n’est pas une reverie: In Praise of the Obsolete by Olympia Kazi The Architecture of Stanley Tigerman 26 Alumni News Gwathmey Siegel: Inspiration and New York Dozen review by John Hill Transformation See Yourself Sensing by Madeline 16 In The Field: Schwartzman Jugaad Urbanism exhibition review by Tributes to Douglas Garofalo by Stanley Cynthia Barton Tigerman and Ed Mitchell 2 CONSTRUCTS YALE ARCHITECTURE FALL 2011 David Chipperfield David Chipperfield Architects, Neues Museum, façade, Berlin, Germany 1997–2009. -

Aspects of Architectural Drawings in the Modern Era

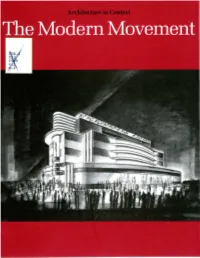

Acknowledgments Fellows of the Program (h Architecture Society 1oiLl13l I /113'1 l~~g \JI ) C,, '"l.,. This exhibition of drawings by European and American archi Darcy Bonner Exhibition tects of the Modern Movement is the fifth in The Art Institute of Laurence Booth The Modern Movement: Selections from the Chicago's Architecture in Context series. The theme of Modern William Drake, Jr. Permanent Collection April 9 - November 20, 1988 ism became a viable exhibition topic as the Department of Archi Lonn Frye Galleries 9 and 10, The Art Institute of Chicago tecture steadily strengthened over the past five years its collection Michael Glass Lectures of drawings dating from the first four decades of this century. In Joseph Gonzales Dennis P. Doordan, Assistant Professor of Architec the case of some architects, such as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Bruce Gregga tural History, University of Illinois at Chicago, "The Ludwig Hilberseimer, Paul Schweikher, William Deknatel, and Marilyn and Modern Movement in Architectural Drawin gs," James Edwin Quinn, the drawings represented in this exhibition Wilbert Hasbrouck Wednesday, April 27, 1988,at 2:30 p.m. , at The Art are only a small selection culled from the large archives of their Scott Himmel Institute of Chicago. Admission by ticket only. For reservations, telephone 443-3915. drawings that have been donated to the Art Institute. In the case Helmut Jahn of European Modernists whose drawings rarely come on the mar James L. Nagle Steven Mansbach, Acting Associate Dean of the ket, such as Eric Mendelsohn, J. J. P. Oud, and Le Corbusier, the Gordon Lee Pollock Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, Na Art Institute has acquired drawings on an individual basis as John Schlossman tional Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., "Reflections works by these renowned architects have become available. -

In Response to a Recent Outbreak of Gang Warfare Violence at the Robert

In response to a recent outbreak of gang warfare violence at the Robert Taylor Homes in Chicago that left ten people dead over a weekend, the Director of the Chicago Housing Authority, Vincent Lane, wanted to have the Chicago police conduct a warrantless sweep search of the Taylor Homes, and to require residents to agree to such searches as a condition in their housing leases. The ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union) has challenged the constitutionality of the sweep search Director Lane wanted. The ACLU also indicated that it would vigorously challenge in court any policy of the Chicago Housing Authority that makes agreement to warrantless searches a condition of living in public housing. Under the circumstances prevailing at the Robert Taylor Homes would warrantless police sweep searches of tenants' apartments be morally justifiable? ANSWER: No: This is a difficult question that requires balancing the fundamental interest of public housing residents in security from life threatening violent criminal behavior and their basic moral right to privacy in their homes. In this case it seems that the balance must be struck in favor of the right of privacy. Given the widespread possession and easy availability of guns in the United States, it is uncertain how effective warrantless sweep searches would be, even if done frequently. On the other hand, the searches would have to be very thorough and intrusive in light of the ease with which a person can hide a gun. The situation at the Robert Taylor Homes is tragic and frightening, but dispensing with a warrant requirement for searches of apartment is not an ethically appropriate response to it. -

Read This Issue

Look to the rock from which you were hewn Vol. 28, No. 1, Winter 2004 chicago jewish historical society chicago jewish history IN THIS ISSUE Martin D. Kamen— Science & Politics in the Nuclear Age From the Archives: Synagogue Project Dr. Louis D. Boshes —Memorial Essay & Oral History Excerpts “The Man with the Golden Fingers” Report: Speaker Ruth M. Rothstein at CJHS Meeting Harold Fox measures Rabbi Morris Gutstein of Congregation Shaare Tikvah for a kosher suit. Courtesy of Harold Fox. African-American (Nate Duncan), and one Save the Date—Sunday, March 21 Mexican (Hilda Portillo)—who reminisce Author Carolyn Eastwood to Present about interactions in the old neighborhood and tell of their struggles to save it and the “Maxwell Street Kaleidoscope” Maxwell Street Market that was at its core. at Society Open Meeting Near West Side Stories is the winner of a Book Achievement Award from the Midwest Dr. Carolyn Eastwood will present “Maxwell Street Independent Publishers’ Association. Kaleidoscope,” at the Society’s next open meeting, Sunday, There will be a book-signing at the March 21 in the ninth floor classroom of Spertus Institute, 618 conclusion of the program. South Michigan Avenue. A social with refreshments will begin at Carolyn Eastwood is an adjunct professor 1:00 p.m. The program will begin at 2:00 p.m. Invite your of Anthropology at the College of DuPage friends—admission is free and open to the public. and at Roosevelt University. She is a member The slide lecture is based on Dr. Eastwood’s book, Near West of the CJHS Board of Directors and serves as Side Stories: Struggles for Community in Chicago’s Maxwell Street recording secretary. -

Brutalism? Some Remarks About a Polemical Name, Its Definition, and Its Use to Designate a Brazilian Architectural Trend

Published at En Blanco n.9/2012 pages 130-2 Avaliable at: http://www.tccuadernos.com/enblanco_numero.php?id=86 Brutalism? Some Remarks About a Polemical Name, its Definition, and its Use to Designate a Brazilian Architectural Trend Ruth Verde Zein [email protected] Mackenzie University São Paulo, Brazil Abstract The term Brutalism is both used and ignored in the architectural literature of the second half of the twentieth century. A thorough analysis of the term shows that it does not have a single, agreed-upon meaning. Although its definition and frequent use have not provided an unequivocal characterization of a Brutalist “essence,” to use Reyner Banham’s words, there seems to be no shortage of architecture identified as Brutalist, even if they are only superficially related. Paradoxically, instead of disregarding the term as inappropriate or vague, we might consider it adequate if we agree that what is common to all the architecture referred to as Brutalist is nothing more than their appearance. By accepting a non-essentialist definition of this movement, one may correctly apply the term to a number of different works, from different places, designed between 1950 and 1970. For the most part, what really connects these buildings is not their essence but their surface, not their inner characteristics but their extrinsic ones. Such a straightforward definition, encompassing the broad variety of Brutalist works, has the merit of providing a working definition of a broadly influential if understudied movement in modern architecture. 1 Fifty years after Brasilia’s inauguration in 1960, Brazilian architecture remains stuck in the same frozen images of a glorious moment in history. -

TOM FINKELPEARL (TF) Former Deputy Director of P.S

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART ORAL HISTORY PROGRAM INTERVIEW WITH: TOM FINKELPEARL (TF) Former Deputy Director of P.S. 1 INTERVIEWER: JEFF WEINSTEIN (JW) Arts & Culture Journalist / Editor LOCATION: THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART DATE: JUNE 15, 2010 BEGIN AUDIO FILE PART 1 of 2 JW: I‟m Jeff Weinstein and we are sitting in the Architecture and Design conference room at the education and research building of The Museum of Modern Art on Tuesday, 3:30, June 15th, and I‟m talking to… TF: 2010. JW: 2010. Is it Thomas or Tom? TF: Tom. JW: Tom Finkelpearl. And we‟re going to be talking about his relationship to P.S. 1. Hello. Could you tell me a little background: where you were born, when, something about your growing up and your education? TF: Okay. Well, I was born in 1956 in Massachusetts. My mom was an artist and my dad was an academic. So, actually, you know, I had this vision of New York City from when I was a kid, which was, going to New York City and seeing, like, abstract expressionist shows. We had a Kline in our front hall. They had a de Kooning on consignment, but they didn‟t have the three hundred and fifty dollars. And so the trajectory of my early childhood was that I always had this incredible vision of coming to New York City and working in the arts. Then actually, I went undergraduate to Princeton. I was a visual arts and art history major, so I was an artist when I started P.S. -

Newsletter the Society of Architectural Historians

NEWSLETTER THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS OCTOBER 1976 VOL. XX NO. 5 PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS 1700 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19103 • Marian C. Donnelly, President • Editor: Thomas M. Slade, 3901 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20008 • Associate Editor: Dora P. Crouch, School of Architecture RPI, Troy, New York 12181 • Assistant Editor: Richard Guy Wilson, 1318 Qxford Place, Charlottesville, Virginia22901. SAH NOTICES 1977 Annual Meeting, Los Angeles-February 2-6. Adolf K. CONTRIBUTIONS OF BACK ISSUES OF SAH Placzek, Columbia University, is general chairman and David JOURNAL REQUESTED Gebhard, University of California, Santa Barbara, is local chairman. The Board of Directors of SAH voted at their May, 1976 Sessions will be held at the Biltmore Hotel February 3, 4 and 5. meeting to request those members who have the back (For a complete listing, please refer to the April1976 issue of the issues of the SAH Journal listed below and are willing to Newsletter.) The College Art Association of America will be part with them to donate them to the central office: Vols. meeting at the Hilton Hotel (a few blocks from the Biltmore) at I-VIII (1940-1949)- all numbers; Vol. IX (1950)-nos. 1, 2, 3; Vol. X (1951) - nos. I & 3; Vol. XI (1952)-nos. I, 2, the same time. As is customary, registration with either organiza tion entitles participants to attend either SAH or CAA sessions, 4; Vol. XII (1953) - no.-2; Vol. XIII (1954) - nos. I & 2; and a fruitful scholarly exchange is anticipated. Vol. XIV (1955)- all numbers; Vol. -

11.941 Learning by Comparison: First World/Third World Cities Fall 2008

MIT OpenCourseWare http://ocw.mit.edu 11.941 Learning by Comparison: First World/Third World Cities Fall 2008 For information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms. DESIGN Principles & Practices: An International Journal Volume 3, Number 4 The Impact of Urban Design Elements on the Successes and Failures of Modern Multi-family Housing: A Comparative Study of Robert Taylor Homes, Chicago and HanGang Apart Complex, Seoul Jae Seung Lee www.design-journal.com DESIGN PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICES: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL http://www.DesignJournal.com First published in 2009 in Melbourne, Australia by Common Ground Publishing Pty Ltd www.CommonGroundPublishing.com. © 2009 (individual papers), the author(s) © 2009 (selection and editorial matter) Common Ground Authors are responsible for the accuracy of citations, quotations, diagrams, tables and maps. All rights reserved. Apart from fair use for the purposes of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act (Australia), no part of this work may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. For permissions and other inquiries, please contact <cg[email protected]>. ISSN: 18331874 Publisher Site: http://www.DesignJournal.com DESIGN PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICES: AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL is peer reviewed, supported by rigorous processes of criterionreferenced article ranking and qualitative commentary, ensuring that only intellectual work of the greatest substance and highest significance is published. Typeset in Common Ground Markup Language using CGCreator multichannel typesetting system http://www.commongroundpublishing.com/software/ The Impact of Urban Design Elements on the Successes and Failures of Modern Multi-family Housing: A Comparative Study of Robert Taylor Homes, Chicago and HanGang Apart Complex, Seoul Jae Seung Lee, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Massachusetts, USA Abstract: This study explores the role of urban design in the successes and failures of modern multi- family housing developments. -

Search for Conceptual Framework in Architectural Works of Muzharullslam .'

:/ • .. Search for Conceptual Framework in Architectural Works of Muzharullslam .' 111111111 1111111111111111111111111 1191725# Mohammad Foyez Ullah This thesis is submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture August, 1997 • Department of Architecture Bangladesh University of Engineering & Technology Dhaka. Bangladesh . II DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE BANGLADESH UNIVERSIlY OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY Dhaka 1000 On this day, the 14'h August, Thursday, 1997, the undersigned hereby recommends to the Academic Council that the thesis titled "Search for Conceptual Framework in Architectural Works of Muzharul Islam" submitted by Mohammad Foyez Ullah, Roll no. 9202, Session 1990-91-92 is acceptable in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture. Dr. M. Shahidul Ameen Associate Professor and Supervisor Department of Architecture Bangladesh University of Engineering & Technology Professor Faruque A. U. Khan Dean, Faculty of Architecture and Planning Bangladesh University of Engineering & Technology ~ Professor Khaleda Rashid Member ---------- Head, Department of Architecture Bangladesh University of Engineering & Technology ~<1 ';;5 Member~n*-/. Md. Salim Ullah Senior Research Architect (External) Housing and Building Research Institute Dar-us-Salam, Mirpur III To my Father IV Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincerest thank to Dr. M. Shahidul Ameen for supervising the thesis and for his intellectual impulses that he offered in making the thesis a true critical discourse. lowe my sincerest thank to Professor Meer Mobashsher Ali for his commitment to make the research on this eminent architect a reality. I am extremely grateful to Muzharul Islam. who even at his age of 74 showed his ultimate modesty by sharing his experiences and knowledge with me, which helped me to see his enterprises in a truer enlightened way. -

EVALUATION of the URBAN INITIATIVES: Anti-Crime

f U.u-(;(;L40b.+ Contract HC-5231 EVALUATION OF THE URBAN INITIATIVES ANTI-CRIME PROGRAM CHICAGO, IL, CASE STUDY 1984 Prepared for: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research Prepared by: Police Foundation John F. Kennedy School of Government The views and conclusions presented in this report are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Department of Housing and Urban Development or of the United States Government I This report is one in a series that comprises a comprehensive evaluation of the Public Housing Urban Initiatives Anti-Crime Demonstration. The Final Report provides an integrated analysis of the design, implementation and impact of the entire demonstration, and each of the 15 site-specific case studies analyzes the implementation and impact of the programs at individual partici pating local housing authorities. The complete set of reports includes: Evaluation of the Urban Initiatives Anti-Crime Program: Final Report Evaluation of the Urban Initiatives Anti-Crime Program: Baltimore, MD, Case Study Charlotte, NC, Case Study Chicago, IL, Case Study Cleveland, OH, Case Study Dade County, FL, Case Stu~ Hampton, VA, Case Study Hartford, CT, Case Stu~ Jackson,1 , Case Study Jersey City, NJ, Case Study Louisville, KY, Case Study Oxnard County, CA, Case Study San Antonio, TX, Case Study Seattle, WA, Case Study Tampa, FL, Case Study Toledo, OH, Case Study Each of the above reports is available from HUD USER for a handling charge. For information contact: HUD USER Post Office Box 280 Germantown, MD 20874 (301) 251-5154 -. II PREFACE The Urban Initiatives Anti-Crime Demonstration was created by the Public Housing Security Demonstration Act of 1978. -

The Chicago Housing Authority 10

the ,~ i J. Popkin,Victoria E. Gwiasda,Lynn M. Olson,[_) inis P. Rosenbaum,and LarryBuron FOREWORD BY REBECCA M. BLANK J The Hidden War 1£4/-7~ The Hidden War Crime and the Tragedy of Public Housing in Chicago SUSAN J. POPKIN VICTORIA E. GWIASDA LYNN M. OLSON DENNIS P. ROSENBAUM LARRY BURON .-- IPF~QRERYY ©f~ ~ation~l @iminal Justics Roi~o~c~ 8onii@ (t~¢jR8) Box 6000 Rockville, ~E) 20849o6000 RUTGERS UNIVERSITY PRESS New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The hidden war : crime and the tragedy of public housing in Chicago / Susan J. Popkin... let al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8135-2832-1 (cloth : alk. paper) -- ISBN 0-8135-2833-X (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Chicago Housing Authority. 2. Housing authorities--Illinois-- Chicago. 3. Public housing--Illinois--Chicago. I. Popkin, Susan J. HD7288.78.U52 C44 2000 363.5'85'0977311--dc21 99-056789 British Cataloging-in-Publication data for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2000 by Susan J. Popkin All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Please contact Rutgers University Press, 100 Joyce Kilmer Avenue, Piscataway, NJ 08854-8099. The only exception to this prohibition is "fair use" as defined by U.S. copyright law. Manufactured in the United States of America - Contents LIST OF PHOTOS, FIGURES, AND TABLES VII FOREWORD BY REBECCA M.