Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haiti: Developments and U.S. Policy Since 1991 and Current Congressional Concerns

Order Code RL32294 Haiti: Developments and U.S. Policy Since 1991 and Current Congressional Concerns Updated January 25, 2008 Maureen Taft-Morales Specialist in Latin American Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Clare Ribando Seelke Analyst in Latin American Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Haiti: Developments and U.S. Policy Since 1991 and Current Congressional Concerns Summary Following the first free and fair elections in Haiti’s history, Jean-Bertrand Aristide first became Haitian President in February 1991. He was overthrown by a military coup in September 1991. For over three years, the military regime resisted international demands that Aristide be restored to office. In September 1994, after a U.S. military intervention had been launched, the military regime agreed to Aristide’s return, the immediate, unopposed entry of U.S. troops, and the resignation of its leadership. President Aristide returned to Haiti in October 1994 under the protection of some 20,000 U.S. troops, and disbanded the Haitian army. U.S. aid helped train a civilian police force. Subsequently, critics charged Aristide with politicizing that force and engaging in corrupt practices. Elections held under Aristide and his successor, René Préval (1996-2000), including the one in which Aristide was reelected in 2000, were marred by alleged irregularities, low voter turnout, and opposition boycotts. Efforts to negotiate a resolution to the electoral dispute frustrated the international community for years. Tension and violence continued throughout Aristide’s second term, culminating in his departure from office in February 2004, after the opposition repeatedly refused to negotiate a political solution and armed groups took control of half the country. -

Fao/Giews Food Availability and Market Assessment Mission to Haiti

S P E C I A L R E P O R T FAO/GIEWS FOOD AVAILABILITY AND MARKET ASSESSMENT MISSION TO HAITI 23 May 2016 This report has been prepared by Felix Baquedano (FAO) under the responsibility of the FAO Secretariat with information from official and other sources. Since conditions may change rapidly, please contact the undersigned for further information if required: Paul Racionzer Economist/Team Leader, EST/GIEWS Trade and Markets Division, FAO E-mail: [email protected] Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web www.fao.org at the following URL address: http://www.fao.org/giews/ and http://www.wfp.org/food- security/reports/CFSAM. The Special Alerts/Reports can also be received automatically by E-mail as soon as they are published, by subscribing to the GIEWS/Alerts report ListServ. To do so, please send an E-mail to the FAO-Mail-Server at the following address: [email protected], leaving the subject blank, with the following message: subscribe GIEWSAlertsWorld-L To be deleted from the list, send the message: unsubscribe GIEWSAlertsWorld-L Please note that it is possible to subscribe to regional lists to only receive Special Reports/Alerts by region: Africa, Asia, Europe or Latin America (GIEWSAlertsAfrica-L, GIEWSAlertsAsia-L, GIEWSAlertsEurope-L and GIEWSAlertsLA-L). These lists can be subscribed to in the same way as the worldwide list. Acknowledgements The author would like to thank the authorities of the Ministry of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Rural Development of Haiti and in particular the Sub-structure for Agricultural Statistics and Informatics as well as the National Coordination of Food Security for their assistance and collaboration in the drafting of this report. -

Gender and Resilience

TECHNICAL BRIEF Gender and Resilience How Inclusive Participation in Cattle Management Strengthens Women’s Resilience in Northern Haiti Authored by Jennifer Plantin, with contributions from Carole Pierre and Evelyne Sylvain Photo by Djimmy Regis, November 2020. Pictured: Vital Sefina from APROLIM in Limonade Haiti This brief is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of Chemonics International Inc. and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. 1 USAID/HAITI REFORESTATION PROJECT APRIL 2021 Introduction Women in Haiti are often at social, political, and economic disadvantages compared to their male counterparts, as evidenced by Haiti's ranking in the Gender Inequality Index (152 out of 162 countries) (UNDP, 2020). The gap is especially significant and consequential for rural women who engage primarily in subsistence farming with little to no access to or control over productive assets and financial services. The patriarchal system that persists today exacerbates these entrenched disparities, especially in rural Haiti. These challenges make women more vulnerable to the many shocks Haiti continues to experience, such as food insecurity, natural disasters, climate change, political instability, and economic shocks. One emerging opportunity to improve livelihoods and bolster household resilience while mitigating climate change is inclusive livestock management. International development -

The Election Impasse in Haiti

At a glance April 2016 The election impasse in Haiti The run-off in the 2015 presidential elections in Haiti has been suspended repeatedly, after the opposition contested the first round in October 2015. Just before the end of President Martelly´s mandate on 7 February 2016, an agreement was reached to appoint an interim President and a new Provisional Electoral Council, fixing new elections for 24 April 2016. Although most of the agreement has been respected , the second round was in the end not held on the scheduled date. Background After nearly two centuries of mainly authoritarian rule which culminated in the Duvalier family dictatorship (1957-1986), Haiti is still struggling to consolidate its own democratic institutions. A new Constitution was approved in 1987, amended in 2012, creating the conditions for a democratic government. The first truly free and fair elections were held in 1990, and won by Jean-Bertrand Aristide (Fanmi Lavalas). He was temporarily overthrown by the military in 1991, but thanks to international pressure, completed his term in office three years later. Aristide replaced the army with a civilian police force, and in 1996, when succeeded by René Préval (Inite/Unity Party), power was transferred democratically between two elected Haitian Presidents for the first time. Aristide was re-elected in 2001, but his government collapsed in 2004 and was replaced by an interim government. When new elections took place in 2006, Préval was elected President for a second term, Parliament was re-established, and a short period of democratic progress followed. A food crisis in 2008 generated violent protest, leading to the removal of the Prime Minister, and the situation worsened with the 2010 earthquake. -

Focus on Haiti

FOCUS ON HAITI CUBA 74o 73o 72o ÎLE DE LA TORTUE Palmiste ATLANTIC OCEAN 20o Canal de la Tortue 20o HAITI Pointe Jean-Rabel Port-de-Paix St. Louis de Nord International boundary Jean-Rabel Anse-à-Foleur Le Borgne Departmental boundary Monte Cap Saint-Nicolas Môle St.-Nicolas National capital Bassin-Bleu Baie de Criste NORD - OUEST Port-Margot Cap-Haïtien Mancenille Departmental seat Plaine Quartier Limbé du Nord Caracol Fort- Town, village Cap-à-Foux Bombardopolis Morin Liberté Baie de Henne Gros-Morne Pilate Acul Phaëton Main road Anse-Rouge du Nord Limonade Baie Plaisance Milot Trou-du-Nord Secondary road de Grande Terre-Neuve NORD Ferrier Dajabón Henne Pointe Grande Rivière du Nord Sainte Airport Suzanne Ouanaminthe Marmelade Dondon Perches Ennery Bahon NORD - EST Gonaïves Vallières 0 10 20 30 40 km Baie de Ranquitte la Tortue ARTIBONITE Saint- Raphaël Mont-Organisé 0 5 10 15 20 25 mi Pointe de la Grande-Pierre Saint Michel Baie de de l'Attalaye Pignon La Victoire Golfe de la Gonâve Grand-Pierre Cerca Carvajal Grande-Saline Dessalines Cerca-la-Source Petite-Rivière- Maïssade de-l'Artibonite Hinche Saint-Marc Thomassique Verrettes HAITI CENTRE Thomonde 19o Canal de 19o Saint-Marc DOMINICAN REPUBLIC Pointe Pointe de La Chapelle Ouest Montrouis Belladère Magasin Lac de ÎLE DE Mirebalais Péligre LA GONÂVE Lascahobas Pointe-à-Raquette Arcahaie Saut-d'Eau Baptiste Duvalierville Savenette Abricots Pointe Cornillon Jérémie ÎLES CAYÉMITES Fantasque Trou PRESQU'ÎLE Thomazeau PORT- É Bonbon DES BARADÈRES Canal de ta AU- Croix des ng Moron S Dame-Marie la Gonâve a Roseaux PRINCE Bouquets u Corail Gressier m Chambellan Petit Trou de Nippes â Pestel tr Carrefour Ganthier e Source Chaude Baradères Anse-à-Veau Pétion-Ville Anse d'Hainault Léogâne Fond Parisien Jimani GRANDE - ANSE NIPPES Petite Rivières Kenscoff de Nippes Miragoâne Petit-Goâve Les Irois Grand-Goâve OUEST Fonds-Verrettes L'Asile Trouin La Cahouane Maniche Camp-Perrin St. -

Haiti: Situation Snapshot in the Idps Camps (May 2013)

Haiti: Situation Snapshot in the IDPs Camps (May 2013) 320,000 people are still living in 385 camps. 86 camps (22%) are particularly vulnerable to hydro-meteorological hazards (oods, landslides). Key figures Comparative maps from 2010 to 2013 of the number of IDPs in the camps Critical needs in camps by sector Camp Management: = 2010 2011 320 051 IDPs Anse-à-Galets Arcahaie Croix des bouquets Around 230,000 could still live in the camps at the end 2013 accor- ding to the most optimistic projections. It is necessary to continue Pointe -à-Raquette Cabaret eorts to provide solutions for return. = (52%) 166 158 Cité Soleil Cornillon Tabarre Thomazeau . Distribution of transitional shelters, Delmas . Grants rental houses, = (48%) Port-au-Prince 153 893 Gressier Pétion Ville Ganthier . Provision of livelihood Petit- Grand- Léogane Carrefour . Mitigation work in the camps. Goave Goave Kenscoff Source : DTM_Report_March 2013, Eshelter-CCCM Cluster Fact sheet Vallée = 385 camps de Jacmel Bainet Jacmel WASH: According to the latest data from the DTM made in March 2013: Number of IDPs and camps under . 30% of displaced families living in camps with an organization forced eviction 2012 2013 dedicated to the management of the site . 88% of displaced households have latrines/toilets in camps. 9% of displaced households have access to safe drinking water within the camps. = 73,000 individuals . 23% of displaced households have showers in the camps. (21,000 households) Source : DTM_Report_March 2013 = 105 camps of 385 are at risk of forced eviction Health: Malnutrition According to the 2012-2013 nutrition report screening of FONDEFH in 7 camps in the metropolitan area with a population of 1675 children and 1,269 pregnant women: Number of IDPs and camps from 2010 Number of IDPs . -

Assessment of Haitian Coffee Value Chain

Assessment of Haitian Coffee Value Chain Fernando Rodríguez, Nora Patricia Castañeda, Mark Lundy A participatory assessment of coffee chain actors in southern Haiti assessment Copyright © 2011 Catholic Relief Services Catholic Relief Services 228 West Lexington Street Baltimore, MD 21201-3413 USA Cover photo: Coffee plants in Haiti. CRS staff. Download this and other CRS publications at www.crsprogramquality.org Assessment of HAitiAn Coffee VAlue Chain A participatory assessment of coffee chain actors in southern Haiti July 12–August 30, 2010 Table of Contents Abbreviations and Acronyms . iii 1 Executive Summary. IV 2 Introduction. 1 3 Relevance of Coffee in Haiti. 1 4 Markets . 4 5 Coffee Chain Analysis. 5 6 Constraints Analyses. 17 7 Recommendations . 19 Glossary . 22 References . 24 Annexes . 25 Annex 1: Problem Tree. 25 Annex 2: Production Solution Tree. 26 Annex 3: Postharvest Solution Tree . 27 Annex 4: Marketing Solution Tree. 28 Annex 5: Conclusions Obtained with Workshops Participants. 29 Figures Figure 1: Agricultural sector participation in total GDP. 1 Figure 2: Coffee production. 3 Figure 3: Haitian coffee exports. 4 Figure 4: Coffee chain in southern Haiti. 6 Figure 5: Potential high-quality coffee municipalities in Haiti. 9 Tables Table 1: Summary of chain constraints and strategic objectives to address them. IV Table 2: Principal coffee growing areas and their potential to produce quality coffee. 2 Table 3: Grassroots organizations and exporting regional networks. 3 Table 4: Land distribution by plot size . 10 Table 5: Coffee crop area per department in 1995 . 10 Table 6: Organizations in potential high-quality coffee municipalities. 12 Table 7: Current and potential washed coffee production in the region . -

DG Haiti Info Brief 11 Feb 2010

IOMIOM EmergencyEmergency OperationsOperations inin HaitiHaiti InformationInformation BriefingBriefing forfor MemberMember StatesStates Thursday,Thursday, 1111 FebruaryFebruary 20102010 INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION 1 ObjectivesObjectives InIn thethe spiritspirit ofof “Member“Member StateState Ownership”:Ownership”: •• ToTo reportreport toto youyou onon howhow youryour moneymoney isis beingbeing spent.spent. •• ToTo demonstratedemonstrate IOM’sIOM’s activityactivity inin thethe UNUN ClusterCluster System.System. •• ToTo shareshare somesome impressionsimpressions fromfrom mymy recentrecent visitvisit toto HaitiHaiti (4-8(4-8 Feb)Feb) •• ToTo appealappeal forfor sustainedsustained supportsupport ofof Haiti.Haiti. INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION 2 OutlineOutline 1.1. SituationSituation inin HaitiHaiti 2.2. IOMIOM HaitiHaiti StaffingStaffing andand CapacityCapacity 3.3. EmergencyEmergency OperationsOperations andand PartnershipsPartnerships 4.4. DevelopmentDevelopment PlanningPlanning 5.5. ResourceResource MobilizationMobilization 6.6. ChallengesChallenges andand OpportunitiesOpportunities INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION 3 I.I. SituationSituation UpdateUpdate GreatestGreatest HumanitarianHumanitarian TragedyTragedy inin thethe WesternWestern HemisphereHemisphere 212,000212,000 dead;dead; 300,000300,000 injured;injured; 1.91.9 millionmillion displaceddisplaced (incl.(incl. 450,000450,000 children);children); 1.21.2 millionmillion livingliving inin spontaneousspontaneous settlementssettlements incl.incl. 700,000700,000 -

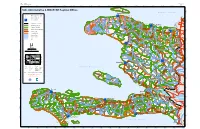

")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un ")Un

HAITI: 1:900,000 Map No: ADM 012 Stock No: M9K0ADMV0712HAT22R Edition: 2 30' 74°20'0"W 74°10'0"W 74°0'0"W 73°50'0"W 73°40'0"W 73°30'0"W 73°20'0"W 73°10'0"W 73°0'0"W 72°50'0"W 72°40'0"W 72°30'0"W 72°20'0"W 72°10'0"W 72°0'0"W 71°50'0"W 71°40'0"W N o r d O u e s t N " 0 Haiti: Administrative & MINUSTAH Regional Offices ' 0 La Tortue ! ° 0 N 2 " (! 0 ' A t l a n t i c O c e a n 0 ° 0 2 Port de Paix \ Saint Louis du Nord !( BED & Department Capital UN ! )"(!\ (! Paroli !(! Commune Capital (!! ! ! Chansolme (! ! Anse-a-Foleur N ( " Regional Offices 0 UN Le Borgne ' 0 " ! 5 ) ! ° N Jean Rabel " ! (! ( 9 1 0 ' 0 5 ° Mole St Nicolas Bas Limbe 9 International Boundary 1 (!! N o r d O u e s t (!! (!! Department Boundary Bassin Bleu UN Cap Haitian Port Margot!! )"!\ Commune Boundary ( ( Quartier Morin ! N Commune Section Boundary Limbe(! ! ! Fort Liberte " (! Caracol 0 (! ' ! Plaine 0 Bombardopolis ! ! 4 Pilate ° N (! ! ! " ! ( UN ( ! ! Acul du Nord du Nord (! 9 1 0 Primary Road Terrier Rouge ' (! (! \ Baie de Henne Gros Morne Limonade 0 )"(! ! 4 ! ° (! (! 9 Palo Blanco 1 Secondary Road Anse Rouge N o r d ! ! ! Grande ! (! (! (! ! Riviere (! Ferrier ! Milot (! Trou du Nord Perennial River ! (! ! du Nord (! La Branle (!Plaisance ! !! Terre Neuve (! ( Intermittent River Sainte Suzanne (!! Los Arroyos Perches Ouanaminte (!! N Lake ! Dondon ! " 0 (! (! ' ! 0 (! 3 ° N " Marmelade 9 1 0 ! ' 0 Ernnery (!Santiag o \ 3 ! (! ° (! ! Bahon N o r d E s t de la Cruz 9 (! 1 ! LOMA DE UN Gonaives Capotille(! )" ! Vallieres!! CABRERA (!\ (! Saint Raphael ( \ ! Mont -

Hti Irma Snapshot 20170911 En.Pdf (English)

HAITI: Hurricane Irma – Humanitarian snapshot (as of 11 September 2017) Hurricane Irma, a category 5 hurricane hit Haiti on Thursday, September 7, 2017. On HAITI the night of the hurricane, 12,539 persons Injured people Bridge collapsed were evacuated to 81 shelters. To date, Capital: Port-au-Prince Severe flooding 6,494 persons remain in the 21 centers still Population: 10.9 M Damaged crops active. One life was lost and a person was recorded missing in the Centre Department Partially Flooded Communes while 17 people were injured in the Artibonite Damaged houses Injured people 6,494 Lachapelle departments of Nord, Nord-Ouest and Ouest. Damaged crops Grande Saline persons in River runoff or flooding of rivers caused Dessalines Injured people Saint-Marc 1 dead partial flooding in 22 communes in the temporary shelters Centre 1 missing person departments of Artibonite, Centre, Nord, Hinche Port de Paix out of 12,539 evacuated Cerca Cavajal Damaged crops Nord-Est, Nord-Ouest and Ouest. 4,903 Mole-St-Nicolas houses were flooded, 2,646 houses were Nord Limonade NORD-OUEST Cap-Haitien badly damaged, while 466 houses were Grande Rivière du Nord severely destroyed. Significant losses were Pilate Gros-Morne also recorded in the agricultural sector in the Nord-Est Bombardopolis Ouanaminthe Ouanaminthe (severe) NORD departments of Centre, Nord-Est and Fort-Liberté Gonaive Nord-Ouest. Caracol NORD-EST Ferrier Terrier-Rouge 21 The Haitian Government, with the support of Trou-du-Nord ARTIBONITE humanitarian partners, is already responding Nord-Ouest active Hinche in the relevant departments to help the Anse-à-Foleur Port-de-Paix affected population. -

Haiti Earthquake Response Five Year Update

HAITI EARTHQUAKE RESPONSE FIVE-YEAR UPDATE | JANUARY 2015 A Message From the President and CEO Five years after the deadly earthquake devastated Haiti, It’s also important to know that we do this work in millions of Haitians are safer, healthier, more resilient, partnership with the Haitian Red Cross and local Haitian and better prepared for future disasters, thanks to organizations, in order to support and sustain a permanent generous donations to the American Red Cross. culture of preparedness. These donations have provided lifesaving services, Five years is a long time, so it may be hard for some to repaired and constructed homes, built and supported remember the devastation and tremendous needs in Haiti. hospitals, established cholera prevention and treatment I can assure you the Red Cross hasn’t forgotten—and, programs, and helped people and communities rebuild thanks to your help, we have worked with Haitians to and recover since the 2010 Haiti earthquake. These build a better future. donations gave people help—and they gave people hope. Our generous donors—which included major corporations, customers who gave at the cash register, people who donated $10 by text and school children who took Gail McGovern up collections—contributed a total of $488 million to the American Red Cross for our Haiti work. Throughout the past five years, the American Red Cross has pledged to spend the donations for Haiti wisely and Total Funds Spent efficiently, and we believe we have done that. We have and Committed spent or made commitments to spend all $488 million of these donations for the Haiti earthquake for projects and 5% programs impacting more than 4.5 million Haitians. -

UNHAS Haiti Flights Serve Santo Domingo and Port-Au-Prince

United Nations Humanitarian Air Service - Haiti UNHAS Haiti flights serve Santo Domingo and Port-au-Prince, Jacmel, Les Cayes, Jeremie, Cap Haitien, Hinche, Gonaive and Port-de-Paix, Dofour and Petit Goave Flight Schedule - effective, 21st June 2010 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday ETA Morning ETD ETA Morning ETD ETA Morning ETD ETA Morning ETD ETA Morning ETD ETA Morning ETD Santo Domingo 08:00 Santo Domingo 08:00 Santo Domingo 08:00 Santo Domingo 08:00 Santo Domingo 08:00 08:55 Port-au-Prince 09:30 08:55 Port-au-Prince 09:30 08:55 Port-au-Prince 09:30 No Scheduled Flights 08:55 Port-au-Prince 09:30 08:55 Port-au-Prince 09:30 10:25 Santo Domingo 10:25 Santo Domingo 10:25 Santo Domingo 10:25 Santo Domingo 10:25 Santo Domingo ETA Afternoon ETD ETA Afternoon ETD ETA Afternoon ETD ETA Afternoon ETD ETA Afternoon ETD ETA Afternoon ETD Santo Domingo 12:00 Santo Domingo 12:00 Santo Domingo 12:00 Santo Domingo 12:00 Santo Domingo 12:00 12:55 Port-au-Prince 13:30 12:55 Port-au-Prince 13:30 No Scheduled Flights 12:55 Port-au-Prince 13:30 12:55 Port-au-Prince 13:30 12:55 Port-au-Prince 13:30 14:25 Santo Domingo 14:25 Santo Domingo 14:25 Santo Domingo 14:25 Santo Domingo 14:25 Santo Domingo Southern Sector Northern Secotor Southern Sector Northern Sector Southern Sector Special Requests Jacmel Cap Haitien Jacmel Cap Haitien Jacmel Les Cayes Hinche Les Cayes Hinche Les Cayes Jeremie Gonaive Jeremie Gonaive Jeremie Unscheduled Locations & Petit Goave Port-dePaix Port-dePaix Special Requests Dofour Petit Goave Dofour Please take a