Submissions and Meeting Summaries Phase I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For the Ec225 Featured Articles Mexico, All Eyes on a Growing Market

ANOTHER SUCCESS FOR THE EC225 FEATURED ARTICLES MEXICO, ALL EYES ON A GROWING MARKET DAUPHIN AND EC135 ONE THOUSAND AND COUNTING WWW.EUROCOPTER.COMWWW.EUROCOPTER.COMWWWWW.EUE ROROCOPTTERR.CCOMM ROTOR91_GB_V3_CB.indd 1 10/11/11 16:25 Thinking without limits 2 TEMPS FORT A helicopter designed to meet every operational challenge. Even the future. Designed in collaboration with our customers to cope with anything from a business trip to the most advanced SAR mission, the EC175 sets a benchmark for decades to come. The largest and quietest cabin. The highest levels of comfort, accessibility and visibility. The lowest fuel cost and CO2 emissions per seat. The EC175 is first in its class for them all. When you think future-proof, think without limits. ROTOR JOURNAL - NO. 91 - OCTOBER/NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2011 new ROTOR EC175Bus indd 1 18/11/10 19:14:44 ROTOR91_GB_V3_CB.indd 2 10/11/11 16:25 EDITORIAL 03 STRENGTHENING OUR LOCAL PRESENCE TO BETTER SERVE YOU Reinforcing our proximity to under the auspices of a joint venture with customers remains one of the local manufacturer Kazakhstan En- our strategic priorities as we gineering. In addition to the assembly believe we can best support line, the new entity will also provide lo- your success by being close cally based maintenance and training © Daniel Biskup to you. With this in mind, we are con- services. We are also taking steps to tinuing to make investments to best strengthen our presence in Brazil, where meet your needs. In all the countries in a new EC725 assembly line is scheduled which we are based, our goal is to gen- to go into operation in the very near fu- erate more added value locally and to ture. -

Second Session Forty-Eighth General Assembly

PROVINCE OF NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY Second Session Forty-Eighth General Assembly Proceedings of the Standing Committee on Resources May 9, 2017 - Issue 4 Department of Advanced Education, Skills and Labour Published under the authority of the Speaker of the House of Assembly Honourable Tom Osborne, MHA RESOURCE COMMITTEE Department of Advanced Education, Skills and Labour Chair: Brian Warr, MHA Vice-Chair: Kevin Parsons, MHA Members: Derrick Bragg, MHA David Brazil, MHA Jerry Dean, MHA John Finn, MHA Lorraine Michael, MHA Pam Parsons, MHA Clerk of the Committee: Sandra Barnes Appearing: Department of Advanced Education, Skills and Labour Hon. Gerry Byrne, MHA, Minister Genevieve Dooling, Deputy Minister Glenn Branton, Chief Executive Officer, Labour Relations Board Debbie Dunphy, Assistant Deputy Minister, Corporate Services and Policy Rob Feaver, Director, Student Financial Services Bren Hanlon, Departmental Controller Gordon MacGowan, Executive Assistant Walt Mavin, Director, Employment and Training Programs Donna O’Brien, Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Services Delivery John Tompkins, Director of Communications Also Present Ivan Morgan, Researcher, Third Party Office Jenna Shelley, Student Researcher, Official Opposition Office James Sheppard, Researcher, Official Opposition Office May 9, 2017 RESOURCE COMMITTEE The Committee met at approximately 9:05 a.m. Minister Byrne, we’ll turn it over to you for your in the House of Assembly. opening remarks. You have 15 minutes, and you can ask your staff as well to introduce CHAIR (Warr): Good Morning. themselves. Welcome, I guess to the final chapter of our Thank you, Sir. Estimates Committee meetings for Resource. Before we get underway, just some MR. BYRNE: Mr. Chair, I thank you again for housekeeping duties and they are the minutes of leaving the best for last. -

Third Session Forty-Eighth General Assembly

PROVINCE OF NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY Third Session Forty-Eighth General Assembly Proceedings of the Standing Committee on Resources April 24, 2018 - Issue 3 Department of Advanced Education, Skills and Labour Published under the authority of the Speaker of the House of Assembly Honourable Perry Trimper, MHA RESOURCE COMMITTEE Department of Advanced Education, Skills and Labour Chair: Brian Warr, MHA Members: Derrick Bragg, MHA Jerry Dean, MHA John Finn, MHA Jim Lester, MHA Lorraine Michael, MHA Pam Parsons, MHA Tracey Perry, MHA Clerk of the Committee: Kimberley Hammond Appearing: Department of Advanced Education, Skills and Labour Hon. Al Hawkins, MHA, Minister Genevieve Dooling, Deputy Minister Bren Hanlon, Departmental Controller Debbie Dunphy, Assistant Deputy Minister, Corporate Services Donna O’Brien, Assistant Deputy Minister, Regional Service Delivery Walt Mavin, Director, Employment & Training Fiona Langor, Assistant Deputy Minister, Workforce Development Candice Ennis-Williams, Assistant Deputy Minister, Post-Secondary Margot Pitcher, Executive Assistant Jacquelyn Howard, Director of Communications Glenn Branton, Chief Executive Officer, Labour Relations Board Also Present Barry Petten, MHA James Sheppard, Researcher, Official Opposition Office Ivan Morgan, Researcher, Third Party April 24, 2018 RESOURCE COMMITTEE Pursuant to Standing Order 68, Barry Petten, Skills and Labour – I’ll let my staff introduce to MHA for Conception Bay South, substitutes for make sure we’re all online. Tracey Perry, MHA for Fortune Bay - Cape La Hune. MS. DOOLING: Good evening. I’m Genevieve Dooling, Deputy Minister. The Committee met at 6:03 p.m. in the Assembly Chamber. MR. HANLON: Brendan Hanlon, Departmental Controller. CHAIR (Warr): Okay, if we can get ourselves comfortable, we will begin. -

460 NYSE Non-U.S. Listed Issuers from 47 Countries (December 28, 2004)

460 NYSE Non-U.S. Listed Issuers from 47 Countries (December 28, 2004) Share Country Issuer (based on jurisdiction of incorporation) † Symbol Industry Listed Type IPO ARGENTINA (10 DR Issuers ) BBVA Banco Francés S.A. BFR Banking 11/24/93 A IPO IRSA-Inversiones y Representaciones, S.A. IRS Real Estate Development 12/20/94 G IPO MetroGas, S.A. MGS Gas Distribution 11/17/94 A IPO Nortel Inversora S.A. NTL Telecommunications 6/17/97 A IPO Petrobras Energía Participaciones S.A. PZE Holding Co./Oil/Gas Refining 1/26/00 A Quilmes Industrial (QUINSA) S.A. LQU Holding Co./Beer Production 3/28/96 A IPO Telecom Argentina S.A. TEO Telecommunications 12/9/94 A Telefónica de Argentina, S.A. TAR Telecommunications 3/8/94 A Transportadora de Gas del Sur, S.A. TGS Gas Transportation 11/17/94 A YPF Sociedad Anónima YPF Oil/Gas Exploration 6/29/93 A IPO AUSTRALIA (10 ADR Issuers ) Alumina Limited AWC Diversified Minerals 1/2/90 A Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited ANZ Banking/Financial Services 12/6/94 A BHP Billiton Limited BHP Mining/Exploration/Production 5/28/87 A IPO Coles Myer Ltd. CM Retail Operations 10/31/88 A James Hardie Industries N.V. JHX International Bldg. Materials 10/22/01 A National Australia Bank Limited NAB Banking 6/24/88 A Rinker Group Limited (Rinker) RIN Heavy Building Materials Mfg. 10/28/03 A Telstra Corporation Limited TLS Telecommunications 11/17/97 A IPO Westpac Banking Corporation WBK Banking 3/17/89 A IPO WMC Resources Ltd WMC Minerals Development/Prod. -

Going Places

Bristow Group Inc. 2007 Annual Report Going Places Bristow Group Inc. 2000 W Sam Houston Pkwy S Suite 1700, Houston, Texas 77042 t 713.267.7600 f 713.267.7620 www.bristowgroup.com 2007 Annual Report BOARD OF DIRECTORS OFFICERS CORPORATE INFORMATION Thomas C. Knudson William E. Chiles Corporate Offi ces Chairman, Bristow Group Inc.; President, Chief Executive Offi cer Bristow Group Inc. Retired Senior Vice President of and Director 2000 W Sam Houston Pkwy S ConocoPhillips Suite 1700, Houston, Texas 77042 Perry L. Elders Telephone: 713.267.7600 Thomas N. Amonett Executive Vice President and Fax: 713.267.7620 President and CEO, Chief Financial Offi cer www.bristowgroup.com Champion Technologies, Inc. Richard D. Burman Common Stock Information Charles F. Bolden, Jr. Senior Vice President, The company’s NYSE symbol is BRS. Major General Charles F. Bolden Jr., Eastern Hemisphere U.S. Marine Corps (Retired); Investor Information CEO of JACKandPANTHER L.L.C. Michael R. Suldo Additional information on the company Senior Vice President, is available at our web site Peter N. Buckley Western Hemisphere www.bristowgroup.com Chairman, Caledonia Investments plc. Michael J. Simon Transfer Agent Senior Vice President, Mellon Investor Services LLC Stephen J. Cannon Production Management 480 Washington Boulevard Retired President, Jersey City, NJ 07310 DynCorp International, L.L.C. Patrick Corr www.melloninvestor.com Senior Vice President, Jonathan H. Cartwright Global Training Auditors Finance Director, KPMG LLP Our Values Caledonia Investments plc. Mark B. Duncan Senior Vice President, William E. Chiles Global Business Development President & Chief Executive Offi cer, Bristow’s values represent our core beliefs about how we conduct our business. -

Eastern Health: a Case Study on the Need for Public Trust in Health Care Communications

Journal of Professional Communication 1(1):149-167, 2011 Journal of Professional Communication Eastern Health: A case study on the need for public trust in health care communications Heather Pullen★ Hamilton Health Sciences, Hamilton (Canada) A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article Type: The reputation of a large health care organization in Canada’s east- Case Study ernmost province, Newfoundland/Labrador, was shaken by a three-year controversy surrounding decisions made by leaders of Article History: the organization not to disclose that errors had been made in one of Received: 2011-04-10 its laboratories. For breast cancer patients, the presence or absence Revised: 2011-08-04 of hormone receptors in tissue samples is vital since it often changes Accepted: 2011-10-25 the choice of treatment — a choice that can have life-or-death impli- cations. Although Eastern Health learned of its errors in May 2005, Key Words: it was not until five months later, when media broke the story, that Health Communication the organization started informing patients. In May 2007, court Crisis Communication documents revealed that 42 percent of the test results were wrong Information openness and, in the interim, 108 of the affected patients had died. This case Newfoundland study reviews the impact on Eastern Health’s reputation and high- Public Relations lights the communication issues raised by the organization’s reluc- tance to release information. © Journal of Professional Communication, all rights reserved. etween 1997 and 2005, 383 women in Newfoundland/Labrador may not have received appropriate treatment for their breast cancer. -

Notice to Participating Organizations 2005-028

Notice to Participating Organizations --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- August 12, 2005 2005-028 Addition of Market On Close (MOC) Eligible Securities Toronto Stock Exchange will roll out MOC eligibility to the symbols of the S&P/TSX Composite Index in preparation for the quarter end index rebalancing on September 16, 2005. TSX will enable MOC eligibility in two phases: I. S&P/TSX Mid Cap Index will become MOC eligible effective September 6, 2005. II. S&P/TSX Small Cap Index will become MOC eligible effective September 12, 2005. A list of securities for each of these indices follows this notice. To ensure you are viewing the most current list of securities, please visit the Standard and Poor's website at www.standardandpoors.com prior to the above rollout dates. “S&P” is a trade-mark owned by The McGraw-Hill, Companies Inc. and “TSX” is a trade- mark owned by TSX Inc. MOC Eligible effective MOC Eligible effective September 6, 2005 September 12, 2005 S&P TSX Mid Cap S&P TSX Small Cap SYMBOL COMPANY SYMBOL COMPANY ABZ Aber Diamond Corporation AAC.NV.B Alliance Atlantis Communications Inc. ACM.NV.A Astral Media Inc. AAH Aastra Technologies Ltd. ACO.NV.X Atco Ltd. ACE.RV ACE Aviation Holdings Inc. AGE Agnico-Eagle Mines AEZ Aeterna Zentaris Inc. AGF.NV AGF Management Ltd. AGA Algoma Steel Inc. AIT Aliant Inc. ANP Angiotech Pharmaceuticals Inc. ATA ATS Automation Tooling Systems Inc. ATD.SV.B Alimentation Couche-Tard Inc. AXP Axcan Pharma Inc. AU.LV Agricore United BLD Ballard Power Systems Inc. AUR Aur Resources Inc. -

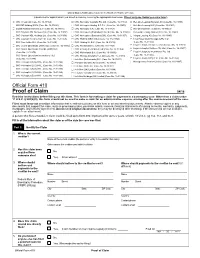

Proof of Claim 04/16 Read the Instructions Before Filling out This Form

United States Bankruptcy Court for the Northern District of Texas Indicate Debtor against which you assert a claim by checking the appropriate box below. (Check only one Debtor per claim form.) ☐ CHC Group Ltd. (Case No. 16-31854) ☐ CHC Helicopter Australia Pty. Ltd. (Case No. 16-31872) ☐ Heli-One Leasing (Norway) AS (Case No. 16-31886) ☐ 6922767 Holding SARL (Case No. 16-31855) ☐ CHC Helicopter Holding S.À R.L. (Case No. 16-31875) ☐ Heli-One Leasing ULC (Case No. 16-31891) ☐ Capital Aviation Services B.V. (Case No. 16-31856) ☐ CHC Helicopter S.A. (Case No. 16-31863) ☐ Heli-One USA Inc. (Case No. 16-31853) ☐ CHC Cayman ABL Borrower Ltd. (Case No. 16-31857) ☐ CHC Helicopters (Barbados) Limited (Case No. 16-31865) ☐ Heliworld Leasing Limited (Case No. 16-31889) ☐ CHC Cayman ABL Holdings Ltd. (Case No. 16-31858) ☐ CHC Helicopters (Barbados) SRL (Case No. 16-31867) ☐ Integra Leasing AS (Case No. 16-31885) ☐ CHC Cayman Investments I Ltd. (Case No. 16-31859) ☐ CHC Holding (UK) Limited (Case No. 16-31868) ☐ Lloyd Bass Strait Helicopters Pty. Ltd. ☐ CHC Den Helder B.V. (Case No. 16-31860) ☐ CHC Holding NL B.V. (Case No. 16-31874) (Case No. 16-31883) ☐ CHC Global Operations (2008) ULC (Case No. 16-31862) ☐ CHC Hoofddorp B.V. (Case No. 16-31861) ☐ Lloyd Helicopter Services Limited (Case No. 16-31873) ☐ CHC Global Operations Canada (2008) ULC ☐ CHC Leasing (Ireland) Limited (Case No. 16-31864) ☐ Lloyd Helicopter Services Pty. Ltd. (Case No. 16-31877) (Case No. 16-31870) ☐ CHC Netherlands B.V. (Case No. 16-31866) ☐ Lloyd Helicopters International Pty. -

Newfoundland and Labrador Studies Importance of a Sense of Place To

Newfoundland and Labrador Studies importance of a sense of place to the creative life of the province. Finally, pathways routinely intersect, and in many of these essays we witness different forms of creative activity crossing with and influencing each other, reinforcing the view of an intimate but complex cultural milieu. Herb Wyile Acadia University James McLeod. Turmoil, as Usual: Politics in Newfoundland and Labrador and the Road to the 20 15 Election. St. John’s: Creative Publishers, 2016. isbn 978-1-77103-081-6 The cottage industry of Newfoundland and Labrador political writ- ings is a very small but passionate market. Every so often, one of the local presses publishes a work that fulfills a broader purpose of being both entertaining and of historic value. The splendidly namedTurmoil, as Usual is one such book. Turmoil, as Usual is a fun, easy read while simultaneously acting as a repository of information. James McLeod is a Telegram reporter who has been covering the province’s political scene since 2011. The book, his first, is a compendium of events that transpired between2012 and 2015, a tumultuous period resulting from a leadership vacuum after populist Danny Williams retired as Progressive Conservative Party leader and Premier. The politicking that McLeod describes would be laughable if it were not such strong evidence of the elitist and anti- quated nature of Newfoundland democracy. It is only by living through the political instability of that time that one can truly appreciate its absurdity. The list of events is too long to get into here. Suffice it to say the cast of characters included multiple 216 newfoundland and labrador studies, 31, 1 (2016) 1719-1726 Book Reviews anointed pc premiers, a Liberal leader who avoids direct answers, an ndp opposition party that self-destructed, and a number of Members of the House of Assembly (mhas) who crossed the floor. -

Gendering Environmental Assessment: Women’S Participation and Employment Outcomes at Voisey’S Bay David Cox1 and Suzanne Mills1,2

ARCTIC VOL. 68, NO. 2 (JUNE 2015) P. 246 – 260 http://dx.doi.org/10.14430/arctic4478 Gendering Environmental Assessment: Women’s Participation and Employment Outcomes at Voisey’s Bay David Cox1 and Suzanne Mills1,2 (Received 12 February 2014; accepted in revised form 3 September 2014) ABSTRACT. This paper examines the effect of Inuit and Innu women’s participation in environmental assessment (EA) processes on EA recommendations, impact benefit agreement (IBA) negotiations, and women’s employment experiences at Voisey’s Bay Mine, Labrador. The literature on Indigenous participation in EAs has been critiqued for being overly process oriented and for neglecting to examine how power influences EA decision making. In this regard, two issues have emerged as critical to participation in EAs: how EA processes are influenced by other institutions that may help or hinder participation and whether EAs enable marginalized groups within Indigenous communities to influence development outcomes. To address these issues we examine the case of the Voisey’s Bay Nickel Mine in Labrador, in which Indigenous women’s groups made several collective submissions pertaining to employment throughout the EA process. We compare the submissions that Inuit and Innu women’s groups made to the EA panel in the late 1990s to the final EA recommendations and then compare these recommendations to employment-related provisions in the IBA. Finally we compare IBA provisions to workers’ perceptions of gender relations at the mine in 2010. Semi-structured interviews revealed that, notwithstanding the recommendations by women’s groups concerning employment throughout the EA process, women working at the site experienced gendered employment barriers similar to those experienced by women in mining elsewhere. -

Issuer Report

Alberta Securities Commission Page 1 of 2 Reporting Issuer List - Cover Page Reporting Issuers Default When a reporting issuer is noted as in default, standardized code symbols (disclosed in the legend below) will be appear in the column 'Nature of Default'. Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this list. A reporting issuer that does not appear on this list or that has inappropriately been noted in default should contact the Alberta Securities Commission promptly. A reporting issuer may be in default and be subject to a Management and Insider Cease Trade Order, but that order will NOT be shown on the list. Legend 1. The reporting issuer has failed to file the following continuous disclosure prescribed by Alberta securities laws: (a) annual financial statements; (b) interim financial statements; (c) an annual or interim management's discussion and analysis (MD&A) or an annual or interim management report of fund performance (MRFP); (d) an annual information form; (AIF); (e) a certification of annual or interim filings under Multilateral Instrument 52-109 Certification of Disclosure in Issuers' Annual and Interim Filings (MI 52-109) ; (f) proxy materials or a required information circular; (g) an issuer profile supplement on the System for Electronic Disclosure By Insiders (SEDI); (h) material change reports; (i) a written update as required after filing a confidential report of a material change; (j) a business acquisition report; (k) the annual oil and gas disclosure prescribed by National Instrument 51-101 Standards of Disclosure -

Printmgr File

™ Scotia Private Pools and Pinnacle Portfolios For more information about Scotia Private Pools and Pinnacle Portfolios: Semi-Annual Report visit: www.scotiabank.com/scotiaprivatepools June 30, 2012 www.scotiabank.com/pinnacleportfolios Money Market Fund call: Scotia Private Short Term Income Pool 1-800-268-9269 (English) Bond Funds 1-800-387-5004 (French) Scotia Private Income Pool Scotia Private High Yield Income Pool Scotia Private American Core-Plus Bond Pool write: Balanced Fund Scotia Asset Management L.P. Scotia Private Strategic Balanced Pool Scotia Plaza Canadian Equity Funds Scotia Private Canadian Value Pool 52nd Floor Scotia Private Canadian Mid Cap Pool 40 King Street West Scotia Private Canadian Growth Pool Toronto, Ontario Scotia Private Canadian Small Cap Pool M5H 1H1 Foreign Equity Funds Scotia Private U.S. Value Pool Scotia Private U.S. Mid Cap Value Pool Scotia Private U.S. Large Cap Growth Pool Scotia Private U.S. Mid Cap Growth Pool Scotia Private International Equity Pool Scotia Private International Small to Mid Cap Value Pool Scotia Private Emerging Markets Pool Scotia Private Global Equity Pool Scotia Private Global Real Estate Pool Pinnacle Portfolios Pinnacle Balanced Income Portfolio Pinnacle Conservative Balanced Growth Portfolio Pinnacle Balanced Growth Portfolio Pinnacle Conservative Growth Portfolio Pinnacle Growth Portfolio ™ Trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia, used under licence. Scotia Private Pools and Pinnacle Portfolios are managed by Scotia Asset Management L.P., a limited partnership wholly-owned directly and indirectly by The Bank of Nova Scotia, and are available through Scotia McLeod. Scotia McLeod is a division of Scotia Capital Inc., a corporate entity separate from, although wholly-owned by, The Bank of Nova Scotia.