How Quirky Is Berkeley? Eugene Tssui's Fish House, Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHSA HP2010.Pdf

The Hawai‘i Chinese: Their Experience and Identity Over Two Centuries 2 0 1 0 CHINESE AMERICA History&Perspectives thej O u r n a l O f T HE C H I n E s E H I s T O r I C a l s OCIET y O f a m E r I C a Chinese America History and PersPectives the Journal of the chinese Historical society of america 2010 Special issUe The hawai‘i Chinese Chinese Historical society of america with UCLA asian american studies center Chinese America: History & Perspectives – The Journal of the Chinese Historical Society of America The Hawai‘i Chinese chinese Historical society of america museum & learning center 965 clay street san francisco, california 94108 chsa.org copyright © 2010 chinese Historical society of america. all rights reserved. copyright of individual articles remains with the author(s). design by side By side studios, san francisco. Permission is granted for reproducing up to fifty copies of any one article for educa- tional Use as defined by thed igital millennium copyright act. to order additional copies or inquire about large-order discounts, see order form at back or email [email protected]. articles appearing in this journal are indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. about the cover image: Hawai‘i chinese student alliance. courtesy of douglas d. l. chong. Contents Preface v Franklin Ng introdUction 1 the Hawai‘i chinese: their experience and identity over two centuries David Y. H. Wu and Harry J. Lamley Hawai‘i’s nam long 13 their Background and identity as a Zhongshan subgroup Douglas D. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Conditions of the Hong Kong Section: Spatial History and Regulatory Environment of Vertically Integrated Developments Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/43t4721n Author Tan, Zheng Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Conditions of the Hong Kong Section: Spatial History and Regulatory Environment of Vertically Integrated Developments A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture by Zheng Tan 2014 © Copyright by Zheng Tan 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Conditions of the Hong Kong Section: Spatial History and Regulatory Environment of Vertically Integrated Developments by Zheng Tan Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Dana Cuff, Chair This dissertation explores the urbanism of Hong Kong between 1967 and 1997, tracing the history of Hong Kong’s vertically integrated developments. It inquires into a Hong Kong myth: How can minimum state intervention gather social resources to build collective urban form? Roughly around the MacLehose Era, Hong Kong began to consciously assume a new vertical order in urban restructuring in order to address the issue of over-crowding and social unrest. British modernist planning provided rich approaches and visions which were borrowed by Hong Kong to achieve its own planning goals. The new town plan and infrastructural development ii transformed Hong Kong from a colonial city concentrated on the Victoria Harbor to a multi-nucleated metropolitan area. The implementation of the R+P development model around 1980 deepened the intermingling between urban infrastructure and superstructure and extended the vertical urbanity to large interior spaces: the shopping centers. -

Chinese Americans in Los Angeles, 1850-1980

LOS ANGELES CITYWIDE HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT Context: Chinese Americans in Los Angeles, 1850-1980 Prepared for: City of Los Angeles Department of City Planning Office of Historic Resources October 2018 National Park Service, Department of the Interior Grant Disclaimer This material is based upon work assisted by a grant from the Historic Preservation Fund, National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior. SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Chinese Americans in Los Angeles, 1850-1980 TABLE OF CONTENTS PURPOSE AND SCOPE 1 CONTRIBUTORS 2 PREFACE 3 HISTORIC CONTEXT 11 Introduction 11 Terms and Definitions 11 Chinese Immigration to California, 1850-1870 11 Early Settlement: Los Angeles’ First Chinatown, 1870-1933 16 Agriculture and Farming, 1870-1950 28 City Market and Market Chinatown, 1900-1950 31 East Adams Boulevard, 1920-1965 33 New Chinatown and China City, 1938-1950 33 World War II 38 Greater Chinatown and Postwar Growth & Expansion, 1945-1965 40 Residential Integration, 1945-1965 47 Chinatown and Chinese Dispersion and Upward Mobility Since 1965 49 ASSOCIATED PROPERTY TYPES AND ELIGIBILITY REQUIREMENTS 55 BIBLIOGRAPHY 79 APPENDICES: Appendix A: Chinese American Known and Designated Resources Appendix B: SurveyLA’s Asian American Historic Context Statement Advisory Committee SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Chinese Americans in Los Angeles, 1850-1980 PURPOSE AND SCOPE In 2016, the City of Los Angeles Office of Historic Resources (OHR) received an Underrepresented Communities grant from the National Park Service (NPS) to develop a National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form (MPDF) and associated historic contexts for five Asian American communities in Los Angeles: Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Thai, and Filipino. -

Department of Environmental and Forest Biology SUNY-ESF

Department of Environmental and Forest Biology SUNY-ESF Annual Report 2011-2012 Front Cover: Collage of images provided by EFB faculty, staff, and students Department of Environmental and Forest Biology Annual Report Summer 2011 Academic Year 2011-2012 Donald J. Leopold Chair, Department of Environmental and Forest Biology SUNY-ESF 1 Forestry Drive Syracuse, NY 13210 Email: [email protected]; ph: (315) 470-6760 July 18, 2012 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction . 4 People . 4 Building . 8 Teaching . 9 Summary of main courses taught by faculty members . 9 Course teaching load summary by faculty members . 12 Undergraduate student advising loads . 14 Curriculum changes . 14 Undergraduate students enrolled in each EFB major . 15 Listing of awards and recognition . 15 Research/Scholarship . .15 Summary of publications/presentations . .15 Science Citation Indices from the Web of Science and Scopus . 17 Summary of grant activity . 18 Patents and Patent Applications . .20 Listing of awards and recognition . 20 Outreach and Service . 20 Enumeration of outreach activities . 20 Summary of grant panel service . 21 Summary of journal editorial board service. 21 Number of journal manuscripts reviewed by faculty. 21 Listing of awards and recognition . 22 Service Learning . 22 Graduate Students. 24 Number of students by degree objectives . 24 Graduate student national fellowships/awards . 24 Graduate recruitment efforts . 24 Graduate student advising . 26 Courses having TA support and enrollment in each . 26 2 Governance Structure . 27 Components. 27 Supporting offices, committees, directors, and coordinators . 28 Budget . 30 State budget allocations . 30 SUNY Research Foundation research incentives funds . 31 Development funds . 32 Student Learning Outcomes Assessment . 33 Objectives 2011-2012 . -

The White House: Inside Story When to Watch from Channel 3-2 – July 2016 a to Z Listings for Channel HD3-1 Are on Pages 18 & 19 24 Frames – Sundays, 1:30 P.M

Q2 3 Program Guide KENW-TV/FM Eastern New Mexico University July 2016 The White House: Inside Story When to watch from Channel 3-2 – July 2016 A to Z listings for Channel HD3-1 are on pages 18 & 19 24 Frames – Sundays, 1:30 p.m. (ends 3rd) After You’ve Gone – Saturdays, 8:00 p.m. Report from Santa Fe – Saturdays, 6:00 p.m. American Woodshop – Saturdays, 6:30 a.m.; Thursdays, 11:00 a.m. Rough Cut – Saturdays, 7:00 a.m. America’s Heartland – Saturdays, 6:30 p.m. Scully/The World Show – Tuesdays, 5:00 p.m. America’s Test Kitchen – Saturdays, 7:30 a.m.; Mondays, 11:30 a.m. Second Opinion – Sundays, 6:30 a.m./6:00 p.m. Antiques Roadshow – Sewing with Nancy – Saturdays, 5:00 p.m. Mondays, 7:00 p.m. & 8:00 p.m. (11th only)/11:00 p.m.; Sit and Be Fit – Monday, Wednesday, Friday, 12:00 noon Sundays, 7:00 a.m. Song of the Mountains – Thursdays, 8:00 p.m. (7th, 14th only) Ask This Old House – Saturdays, 4:00 p.m. Star Gazers – Wednesdays, 10:57 p.m.; Saturdays, 10:57a.m./9:57 p.m.; Austin City Limits – Saturdays, 9:00 p.m./12:00 midnight Sundays, 2:57 p.m./10:57 p.m.; Mondays, 10:27 p.m. BBC Newsnight – Fridays, 5:00 p.m. Steven Raichlen’s Project Smoke II – Thursdays, 11:30 a.m. BBC World News – Weekdays, 6:30 a.m./4:30 p.m. This Old House – Saturdays, 3:30 p.m.; Wednesdays, 10:30 p.m. -

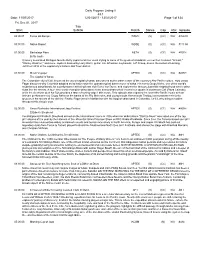

12/31/2017 Daily Program Listing II 11/07/2017 Page 1 of 124

Daily Program Listing II 43.1 Date: 11/07/2017 12/01/2017 - 12/31/2017 Page 1 of 124 Fri, Dec 01, 2017 Title Start Subtitle Distrib Stereo Cap AS2 Episode 00:00:01 Focus On Europe WNVC (S) (CC) N/A #3547H 00:30:00 Native Report WDSE (S) (CC) N/A #1113H 01:00:00 Backstage Pass NETA (S) (CC) N/A #707H Betty Joplin Grammy nominated Michigan favorite Betty Joplin lends her vocal styling to some of the greatest standards ever written. Includes "At Last," "Stormy Weather," and more. Joplin is backed by Larry Barrs, guitar; Jim Alfredson, keyboards; Jeff Shoup, drums. Recorded at Lansing JazzFest 2015 in the capital city's historic Old Town district. 01:30:00 Music Voyager APTEX (S) (CC) N/A #205H The Capital of Salsa The Colombian city of Cali, known as the world capital of salsa, also serves as the urban center of the country's Afro-Pacific culture. Host Jacob Edgar discovers why Columbia adopted as its native style the upbeat tropical dance music of salsa. He meets Grupo Niche, one of the world's most famous salsa bands, for a performance at their private club Dulce con Dulce, and explores the famous Juanchito neighborhood where salsa clubs line the streets. A four- time world champion salsa dance team demonstrates their moves in a square in downtown Cali (Plaza Caicedo), while the electronic duet No DJs provides a taste of cutting-edge Latin music. This episode also explores the local Afro-Pacific music with an intimate performance by Grupo Bahia on the banks of the Rio Melendez, and young bloods Herencia de Timbiqui demonstrate their funky grooves in the streets of the old city. -

Curriculum Vitae HOWARD DAVIS Professor of Architecture

Curriculum Vitae HOWARD DAVIS Professor of Architecture Department of Architecture School of Architecture and Allied Arts University of Oregon Eugene, Oregon 97403 USA (541) 346 3665 office (541) 221 5691 cell [email protected] EDUCATION M. Arch., University of California, Berkeley, 1974 M.S. in Physics, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, 1970 B.S. in Physics, The Cooper Union, New York City, 1968 Brooklyn Technical High School, 1961-64 New York City public schools HONORS AND AWARDS Thomas F. Herman Faculty Achievement Award for Distinguished Teaching, University of Oregon, awarded 2011 ACSA Distinguished Professorship, Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture, awarded 2009 Faculty Excellence Award, University of Oregon, awarded 2008 Best Scholarly Publication in Architecture and Urban Studies, Association of American Publishers, for The Culture of Building, awarded 2000 ACADEMIC AND ADMINISTRATIVE POSITIONS 1995-present Professor of Architecture, University of Oregon. (Member of Ph.D. faculty, Department of Architecture, 2010-) (Member of Center for Housing Innovation [1988-2011]) (Member of faculty in Historic Preservation [1992-]) (Associate member of Center for Asian and Pacific Studies [1994-]) 2009- Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Architecture, University of Oregon 2002-2003 Acting Director, Historic Preservation Program, School of Architecture and Allied Arts, University of Oregon. 2001 Visiting Professor, Department of Architectural Conservation, School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi, India 1997 Visiting Professor of Architecture, University of California, Berkeley 1988-95 Associate Professor of Architecture, University of Oregon. page 1 of 53 1986-88 Assistant Professor of Architecture, University of Oregon. 1984-86 Assistant Professor of Architecture, University of Texas at Austin. 1977-82, 1983-84 Lecturer, Department of Architecture, University of California, Berkeley. -

WEDNESDAY 1 6:00 Pm 6:30 Pm 7:00 Pm 7:30 Pm 8:00 Pm 8:30 Pm 9:00 Pm 9:30 Pm 10:00 Pm 10:30 Pm 11:00 Pm 11:30 Pm Midnight

WEDNESDAY 1 6:00 pm 6:30 pm 7:00 pm 7:30 pm 8:00 pm 8:30 pm 9:00 pm 9:30 pm 10:00 pm 10:30 pm 11:00 pm 11:30 pm Midnight Nova Invisible Universe Revealed Genius By Stephen Hawking What Genius By Stephen Hawking Where Nightly Business One of the most ambitious experiments Are We? Professor Stephen Hawking Are We? Renowned scientist Stephen WCNY HD BBC World News America PBS NewsHour Charlie Rose Tavis Smiley Report in all of astronomy, the Hubble Space challenges three ordinary people to Hawking challenges three ordinary Telescope, is explored. find out what we really are. people to think like a genius. Sara's Ask This Old Rick Steves' Europe Pedal America Cat in the Hat Knows A Lidia's Kitchen Cook's Country Pati's Mexican Weeknight Lidia's Kitchen Cook's Country Curious George Up A House Doorbell, Great Swiss Cities: Women of Red Lot About That! Meet Nature Cat Playground- Ready Jet Go! Solar Crespelle Recipes Fried Chicken and Table Baked! Meals Build A Crespelle Recipes Fried Chicken and Tree/Curious George and Home Gym, Pipes Luzern, Bern, Zurich Rock - Sedona, The Beetles/Tongue Palooza/Small But Big System Bake-Off/Kid- include Celery, Grilled Peppers Baked Egg Better Burger include Celery, Grilled Peppers the Trash George tires of Tom Silva and and Lausanne Enjoy Arizona Ira David Tied The kids meet Nature Cat and his friends Kart Derby Mindy and Artichoke and Test cook Julia Collin Casserole, Salsa Sara's turkey Artichoke and Test cook Julia Collin Create table manners and house Kevin O'Connor a variety of eye- pedals his road