A BRIEF HISTORY of STAPLEHURST from ACORN to OAK by Anita Thompson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Document-0.Pdf

Country Homes 1 HILLSIDE COTTAGES KENWARD ROAD YALDING KENT ME18 6AH £495,000 FREEHOLD The Estate Office, Crampton House [email protected] High Street, Staplehurst www.radfordsestates.co.uk Kent, TN12 0AU 01580 893152 1 HILLSIDE COTTAGES, KENWARD ROAD, YALDING, KENT ME18 6AH PERCHED HIGH UP ON A HILL ON THE OUTSKIRTS OF YALDING VILLLAGE, HILLSIDE COTTAGES COMMANDS BREATHTAKING VIEWS BACK ACROSS THE VALLEY. THE PROPERTY HAS BEEN LOVINGLY REBURBISHED AND EXTENDED IN RECENT YEARS, WITH FURTHER POTENTIAL FOR A KITCHEN EXTENSION AND GARAGE (SUBJECT TO PP). LOCATED ON AN IDYLLIC, QUIET COUNTRY LANE, THIS COTTAGE MUST BE SEEN. ENTRANCE HALL, UTILITY ROOM, SITTING ROOM, INNER HALL, GROUND FLOOR CLOAKROOM, KITCHEN, FIRST FLOOR LANDING, MASTER BEDROOM, FIRST FLOOR BATHROOM, TWO FURTHER BEDROOMS, TOP FLOOR CLOAKROOM, GARDEN & OFF-ROAD PARKING VIEWINGS Strictly by appointment with the Agent as above. DIRECTIONS From the bridge over the river Beult in the centre of Yalding village, proceed along the High Street (B2010) in the direction of West Farleigh. Turn left into Kenward Road by The Walnut Tree Pub. Proceed up Kenward Road for approximately one mile, and the cottage can be found on the right-hand side. DESCRIPTION A traditional farm workers cottage in semi-rural location which has undergone complete renovation by the current owners. The attached property has been completely re-wired and re-plumbed, and extensive insulation installed in the walls and roof. The cottage had a new boiler and central heating system installed in 2017, and new wood burner completes the sitting room. The cottages offers further potential for a single storey kitchen extension to take advantage of the panoramic views, and there is space to build a detached garage (subject to pp). -

September 2020

September 2020 THIS ISSUE: Words from Father Paul Woodpeckers The Woolpack Inn Collier Street in World Ward II Ramblings Sofia’s Lockdown story Jacqui Bakes Speed watch Fibre Broadband in Collier Street Parish Council Notes Councillor retires Community Infrastructure Levy background PAPER DELIVERY There is a paper delivery service to the village at around 6am every morning. It is supplied by Jackie’s News Limited based in Tenterden, they can be contacted on 01580 763183. Cost of delivery is £3.51 a week. KENT MESSENGER VILLAGE COLUMN Rubbish, food waste and small electrical Are you organising a local charity event or items do you have any community news? 14th and 28th September If you would like it to appear in the Kent Messenger for free, please contact: Recycling, food waste and textiles Jenny Scott 01892 459041 7th and 21st September Email: [email protected] Deadline is 9.00 Monday morning Please check www.maidstone.gov.uk for more information. PCSO NICOLA MORRIS If you are worried about crime and antisocial behaviour in your area, I am the local Police Community Support Officer for Collier Street, Laddingford and Yalding. If you would like to talk to me, please ring - Mobile: 07870163411 / Non-emergency: 101 There is a very successful Neighbourhood Watch Scheme in Collier Street involving over 100 residents. However there are many more households within the Parish who are currently not involved in the scheme. If you would like to be part of the NHW scheme and receive notifications of any suspicious activity or crime then please send your email address to Barbara Grandi at: [email protected] 2 Welcome to the September edition! We hope you have all stayed safe and well in these unusual times. -

Hawkhurst the Moor Highgate and All Saints Church Iddenden Green (Sawyers Green) Hawkhurst Conservation Areas Appraisal

Conservation Areas Appraisal Hawkhurst The Moor Highgate and All Saints Church Iddenden Green (Sawyers Green) Hawkhurst Conservation Areas Appraisal The Moor Highgate and All Saints Church Iddenden Green (Sawyers Green) Tunbridge Wells Borough Council in Partnership with Hawkhurst Parish Council and other local representatives N G Eveleigh BA, MRTPI Planning and Building Control Services Manager Tunbridge Wells Borough Council Town Hall, Royal Tunbridge Wells, Kent TN1 1RS September 1999 Printed on environmentally friendly paper Acknowledgements The Borough Council would like to thank Hawkhurst Parish Council and other local representatives for their participation in the preparation of this guidance Contents Section Page 1 Introduction 1 2 Policy Background 3 3 Perceptions of Hawkhurst 10 4 The Evolution of Hawkhurst 11 5 The Evolution and Form of The Moor 12 Pre-1400 12 1400 – 1800 12 1800 – 1950’s 13 1950’s – Present Day 13 6 Character Appraisal for The Moor 14 Context 14 Approaches to the Village 14 Eastern Area 14 North Western Area 18 7 Summary of Elements that Contribute to The Moor Conservation 22 Area’s Special Character 8 Summary of Elements that Detract from The Moor Conservation 24 Area’s Special Character and Opportunities for Enhancement 9 The Evolution and Form of Highgate and All Saints Church 26 Pre-16th Century 26 1500 – 1800 26 Nineteenth Century 26 Twentieth Century 27 10 Character Appraisal for Highgate and All Saints Church 28 Context 28 Approaches to the Village 28 Eastern Approach – Rye Road 28 Western Approach -

Neighbourhood Plan

STAPLEHURST NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN FINAL PLAN 2016 — 2031 MADE 7TH DECEMBER 2016 Staplehurst Parish Council STAPLEHURST NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN FINAL PLAN Made 7th December 2016 This plan has been prepared by: Staplehurst Parish Council, The Parish Office, Village Centre, High Street, Staplehurst, Kent, TN12 0BJ. Digital copies of this document can be downloaded from: www.staplehurstvillage.org.uk www.maidstone.gov.uk / 2 Staplehurst Parish Council / December 2016 / Final Plan / 3 BUILDING A STAPLEHURST FIT FOR THE FUTURE PLAN PERIOD 2016 — 2031 / Staplehurst Parish Council / Neighbourhood Plan / 4 doc. ref: 099_Q_161207_Made-Plan Feria Urbanism is a planning and design studio that specialises in neighbourhood strategies, public participation and community engagement. Established in 2007, we have been involved in a diverse range of projects across the UK and have developed key skills in organising community engagement events to inform excellent planning and design. Contact for further information Richard Eastham | Feria Urbanism | www.feria-urbanism.eu + 44 (0) 7816 299 909 | + 44 (0) 1202 548 676 All maps within this document are reproduced from the Ordnance Survey mapping with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationary Office. © Crown Copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown Copyright and may lead to prosecution and civil proceedings. The Maidstone Borough Council Licence No. 100019636, 2011. Drawings and plans shown are preliminary design studies only and are subject to information available at the time. They are -

Appendix B: Employment and Mixed Use Site Assessments

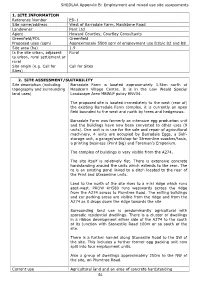

SHEDLAA Appendix B: Employment and mixed use site assessments 1. SITE INFORMATION Reference Number ED-1 Site name/address West of Barradale Farm, Maidstone Road Landowner Pent Ltd Agent Howard Courtley, Courtley Consultants Greenfield/PDL Greenfield Proposed uses (sqm) Approximately 5500 sqm of employment use B1b/c B2 and B8 Site area (ha) 1.9 Is the site urban, adjacent Rural to urban, rural settlement or rural Site origin (e.g. Call for Call for Sites Sites) 2. SITE ASSESSMENT/SUITABILITY Site description (including Barradale Farm is located approximately 1.5km north of topography and surrounding Headcorn Village Centre. It is in the Low Weald Special land uses) Landscape Area MBWLP policy ENV34. The proposed site is located immediately to the west (rear of) the existing Barradale Farm complex, it is currently an open field bounded to the west and north by trees and hedgerows. Barradale Farm was formerly an intensive egg production unit and the buildings have now been converted to other uses (9 units). One unit is in use for the sale and repair of agricultural machinery, 4 units are occupied by Barradale Eggs, a Self- storage unit, a garage/workshop for Streamline coaches/taxis, a printing business (Print Big) and Foreman’s Emporium. The complex of buildings is very visible from the A274. The site itself is relatively flat. There is extensive concrete hardstanding around the units which extends to the rear. The re is an existing pond linked to a ditch located to the rear of the Print and Streamline units. Land to the north of the site rises to a mini ridge which runs east-west. -

Landscape Assessment of Kent 2004

CHILHAM: STOUR VALLEY Location map: CHILHAMCHARACTER AREA DESCRIPTION North of Bilting, the Stour Valley becomes increasingly enclosed. The rolling sides of the valley support large arable fields in the east, while sweeps of parkland belonging to Godmersham Park and Chilham Castle cover most of the western slopes. On either side of the valley, dense woodland dominate the skyline and a number of substantial shaws and plantations on the lower slopes reflect the importance of game cover in this area. On the valley bottom, the river is picked out in places by waterside alders and occasional willows. The railway line is obscured for much of its length by trees. STOUR VALLEY Chilham lies within the larger character area of the Stour Valley within the Kent Downs AONB. The Great Stour is the most easterly of the three rivers cutting through the Downs. Like the Darent and the Medway, it too provided an early access route into the heart of Kent and formed an ancient focus for settlement. Today the Stour Valley is highly valued for the quality of its landscape, especially by the considerable numbers of walkers who follow the Stour Valley Walk or the North Downs Way National Trail. Despite its proximity to both Canterbury and Ashford, the Stour Valley retains a strong rural identity. Enclosed by steep scarps on both sides, with dense woodlands on the upper slopes, the valley is dominated by intensively farmed arable fields interspersed by broad sweeps of mature parkland. Unusually, there are no electricity pylons cluttering the views across the valley. North of Bilting, the river flows through a narrow, pastoral floodplain, dotted with trees such as willow and alder and drained by small ditches. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Planning Committee, 30/11/2017 18:00

PLANNING COMMITTEE MEETING Date: Thursday 30 November 2017 Time: 6.00 p.m. Venue: Town Hall, High Street, Maidstone Membership: Councillors Boughton, Clark, Cox, English (Chairman), Harwood, Munford, Powell, Prendergast, Round (Vice-Chairman), Spooner, Mrs Stockell and Vizzard AGENDA Page No. 1. Apologies for Absence 2. Notification of Substitute Members 3. Notification of Visiting Members 4. Items withdrawn from the Agenda 5. Date of Adjourned Meeting - 7 December 2017 6. Any business the Chairman regards as urgent including the urgent update report as it relates to matters to be considered at the meeting 7. Disclosures by Members and Officers 8. Disclosures of lobbying 9. To consider whether any items should be taken in private because of the possible disclosure of exempt information. 10. Minutes of the meeting held on 9 November 2017 adjourned to 1 - 8 16 November 2017 - Minutes of the adjourned meeting to follow 11. Presentation of Petitions (if any) 12. Reference from the Policy and Resources Committee - Budget 9 Monitoring - Development Control Appeals 13. Deferred Items 10 Issued on 22 November 2017 Continued Over/: Alison Broom, Chief Executive 14. 16/505401 - Vicarage Field At Wares Farm, Linton Hill, Linton, 11 - 28 Kent 15. 16/506436 - The Green Barn, Water Lane, Hunton, Kent 29 - 39 16. 16/507035 - Gibbs Hill Farm, Grigg Lane, Headcorn, Kent 40 - 62 17. 17/500984 - Land Between Ringleside & Ringles Gate, Grigg 63 - 72 Lane, Headcorn, Kent 18. 17/502331 - Land At Woodcut Farm, Ashford Road, 73 - 115 Hollingbourne, Kent 19. 17/503043 - Land South Of Avery Lane And Land South Of 116 - 135 Sutton Road, Otham, Kent 20. -

Hawkenbury Barn Hawkenbury Kent Internal Page Single Pic Full Lifestylehawkenbury Benefit Barn, Pull out Statementhawkenbury, Can Go to Two Ortonbridge, Three Lines

Hawkenbury Barn Hawkenbury Kent Internal Page Single Pic Full LifestyleHawkenbury benefit Barn, pull out statementHawkenbury, can go to two orTonbridge, three lines. TN12 0EA. FirstA simply paragraph, stunning editorial Grade II style,listed short,newly convertedconsidered detached headline barn, benefitslocated in of a living convenient here. ruralOne or location, two sentences with beautiful that convey gardens what and yougrounds would extending say in person. to about 0.6 acres. 4XXX4 2 X Second paragraph, additional details of note about the property.Staplehurst Wording station to 2 add miles value (London and support Bridge fromimage 51 selection. minutes). Tem volum is solor si aliquation rempore puditiunto qui utatis Headcorn station 2.6 miles (London Bridge from 56 minutes). adit, animporepro experit et dolupta ssuntio mos apieturere ommostiMarden station squiati 5 milesbusdaecus (London cus Bridgedolorporum from 47volutem. minutes). M20(J8) 7 miles. Goudhurst 8.5 miles. Cranbrook 7 miles. Tunbridge Wells Third17 miles. paragraph, Ashford additional International details 16.5 of miles note (Londonabout the St property. Pancras Wordingfrom 36 minutes).to add value Ashford and support 17 miles. image Gatwick selection. airport 42Tem miles. volumCentral is London solor si 52aliquation miles. Heathrow rempore puditiuntoairport 63 miles.qui utatis (All times adit,and distancesanimporepro approximate) experit et dolupta ssuntio mos apieturere ommosti squiati busdaecus cus dolorporum volutem. SubThe HeadProperty Hawkenbury Barn is a beautifully newly converted detached barn with the balance of a 10 year Build-Zone Warranty. It offers substantial family/reception accommodation, all set within approximately 0.6 acres of lovely gardens and grounds. Upon entering the front door you are greeted by a breathtaking full Subheight glazed Head reception hall providing space to hang coats and store shoes. -

Staplehurst Tonbridge Tel: +44 (0) 1580 892 888 Kent Fax: +44 (0) 1580 892 852 TN12 0QW

Lodge Road Staplehurst Tonbridge Tel: +44 (0) 1580 892 888 Kent Fax: +44 (0) 1580 892 852 TN12 0QW Travel Information MotorwA1a0 y Map A13 M25 to M20: Dartford Tilbury LONDON Grain Take turn off at Junction 8 on the M20 onto the B2163 towards A205 A2 A20 A228 Sheerness Leeds Castle (The Great Danes Hotel will be on the right). This Gravesend Rochester Orpington route will take you past the entrance to Leeds Castle and through 5 M 20 Chatham A249 A232 M2 7 the villages of Leeds and Langley. When you reach a staggered 2 A2 A2 A225 M2 crossroads (by the Plough Public House) go straight over and Croydon A228 Sittingbourne continue towards Boughton Monchelsea/Linton on the B2163. M26 A25 Maidstone Where the B2163 crosses the A229 (the first set of traffic lights that M M25 20 A25 Sevenoaks A20 you will pass, next to the Cornwallis School) turn left onto the A229. A21 Tonbridge A27 Follow the A229 into Staplehurst (about 6 miles) You will cross a A2 3 8 2 4 2 Staplehurst hump-backed bridge over the railway as you enter Staplehurst. Turn M2 Royal A2 East A2 Ashford right immediately into Station Approach. Turn left into Lodge Road Tunbridge 2 Grinstead 9 about 200 yards along, and you will see Amethyst ahead of you. A264Wells A262 A28 Please report to Security at the gate. Tenterden A26 7 Crowborough A26 A268 The nearest train station is Staplehurst, and is a short walk to our Haywards A21 offices. For train times call 08457 484950. -

Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council Local Plan Habitat Regulations Assessment: Stage 1 (Air Quality Screening)

Appendix4 Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council Local Plan Habitat Regulations Assessment: Stage 1 (Air Quality Screening) July 2018 Tonbridge & Malling Borough Council Mott MacDonald Victory House Trafalgar Place Brighton BN1 4FY United Kingdom T +44 (0)1273 365000 F +44 (0)1273 365100 mottmac.com Tonbridge & Malling Borough Council Gibson Building Tonbridge and Malling Gibson Drive 391898 2 B Kings Hill Borough TMBC HRA StageCouncil 1 Local Plan West Malling Mott MacDonald ME19 4LZ Habitat Regulations Assessment: Stage 1 (Air Quality Screening) July 2018 Mott MacDonald Limited. Registered in England and Wales no. 1243967. Registered office: Mott MacDonald House, 8-10 Sydenham Road, Croydon CR0 2EE, Tonbridge & Malling Borough Council United Kingdom Mott MacDonald | Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council Local Plan Habitat Regulations Assessment: Stage 1 (Air Quality Screening) Issue and Revision Record Revision Date Originator Checker Approver Description A May S. Arora C. Mills C. Mills Draft for comment 2018 J. Brookes B July S. Arora J. Brookes C. Mills Second issue 2018 Document reference: 391898 | 2 | B Information class: Standard This document is issued for the party which commissioned it and for specific purposes connected with the above- captioned project only. It should not be relied upon by any other party or used for any other purpose. We accept no responsibility for the consequences of this document being relied upon by any other party, or being used for any other purpose, or containing any error or omission which is due to an error or omission in data supplied to us by other parties. This document contains confidential information and proprietary intellectual property. -

Appendix 2 Itemised Completions 2019-20.Xlsx

APPENDIX 2: Itemised Completions Site ReferenceSite Application No Address Address2 Decision Date Percentage of onSite PDL Previous / Existing Use AreaSite (net) Eastings Northings Ward Parish Completed (gain) Completed (loss) GainNet Land to the East of, 13/1749 16/503641 Hermitage Lane, Maidstone, Kent, 21-Dec-16 0 F1 33.02573385 156335 Heath 154 154 Land North Of Bicknor Downswood 17/501449 17/501449 Wood, Sutton Road Maidstone, Kent 19-Mar-18 0 14.77579241 152678 And Otham Otham CP 88 88 Land At Stanley Farms, Plain Marden, Kent, Marden And 13/1585 15/508756 Road, TN12 9EH 29-Apr-16 0 F1 5.44574592 144180 Yalding Yalding CP 85 85 Wren's Cross, Upper Stone Maidstone, Kent, 16/505425 16/505425 Street ME15 6HJ 15-Feb-17 100 E 0.4011576264 155370 High Street 75 75 (Fishers Farm) Land North Staplehurst, Kent, Staplehurst 14/505432 14/505432 of, Headcorn Road, TN12 0DT 20-Oct-17 0 F1 17.74578838 143924 Staplehurst CP 57 57 Springfield site, Moncktons Royal Engineers Rd 16/507471 17/502432 Lane, MAIDSTONE 08-Jun-18 100 1.55575568 156885 North 56 56 Boughton Land At Langley Park, Sutton Monchelsea 13/1149 17/501904 Road Maidstone, Kent 01-Nov-17 0 V3 31.63579313 151785 Park Wood CP 54 54 Land West Of, Hermitage 13/1702 15/506324 Lane, Maidstone, Kent 17-May-16 0 F1 9.65573059 155612 Heath 45 45 Sutton Road, Sutton Valence 13/1149 17/504524 Land At Langley Park, Maidstone, Kent 27-Nov-18 0 V3 31.63579313 151785 And Langley 37 37 Land At Cripple Street, Maidstone, Kent, 14/503167 14/503167 Cripple Street ME15 6BA 03-Nov-15 0 N2 2.16576049 153582 -

20161222 Interim Findings on Maidstone Borough Local Plan

INTERIM FINDINGS FROM THE EXAMINATION OF THE MAIDSTONE BOROUGH LOCAL PLAN 22 December 2016 Robert Mellor BSc DipTRP DipDesBEnv DMS MRICS MRTPI An Inspector appointed by the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government The scope of these findings This paper has been produced to address a number of main matters which have been discussed at examination hearings to indicate where main modifications may or may not be required to make the Plan sound. It does not cover every matter but it provides a broad overview. It is also intended to assist in identifying where further work may be needed to support an update of the proposed changes that have already been prepared by the Council and which will form the basis of draft main modifications to the Plan (to be supported by revised sustainability appraisal) which would then be subject to public consultation. Such main modifications are also likely to include additional and typically more detailed matters which have previously been the subject of changes proposed by Maidstone Borough Council. These have been the subject of discussion at Examination hearings. These are interim findings only. Final and fuller conclusions on the matters and issues referred to below will be set out in the Final Report at the end of the Examination process. Matter 1: Duty to Cooperate Issue – Whether the Local Planning Authority and other relevant persons have complied with the Duty to Cooperate? 1. S33A of the P&CPA sets out a statutory ‘Duty to Cooperate’ (DtC) which here applies to Maidstone BC and other local planning authorities, to Kent County Council, and to other persons prescribed by Regulation 4 of the Town and Country Planning (Local Planning) England Regulations 2012 (the Regulations).