Amended Complaint ) for Damages ) and Injunctive and V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trade Marks Journal No: 1842 , 26/03/2018 Class 31 1873621 15

Trade Marks Journal No: 1842 , 26/03/2018 Class 31 1873621 15/10/2009 VANTAGE ORGANIC FOOD PVT. LTD 13/12-A, MALVIYA NAGAR, JAIPUR-302004 RAJASTHAN NO SPECIFY A COMPANY INCORPORATED UNDER THE PROVISIONS OF COMPANIES ACT, 1956. Address for service in India/Agents address: PRATEEK KASLIWAL C-230, GYAN MARG, TILAK NAGAR, JAIPUR 302004 Used Since :01/05/2005 AHMEDABAD AGRICULTURAL, HORTICULTURAL AND FORESTRY PRODUCTS AND GRAIN NOT INCLUDED IN OTHER CLASSES; LIVE ANIMALS; FRESH FRUITS AND VEGETABLES; SEEDS, NATURAL PLANTS AND FLOWERS; FOODSTUFFS FOR ANIMALS, MALT. 5876 Trade Marks Journal No: 1842 , 26/03/2018 Class 31 UTROSTRONG 1936711 16/03/2010 AMIT KUMAR trading as ;M/S. LAKSHYA MEDICAL AGENCY DELHI ROAD RAMPUR MANIHARAN TEH RAMPUR MANI DISTT SAHARANPUR-247001. MARKETING AND TRADING Address for service in India/Attorney address: VINAY MARWAH ADV 292 MODEL TOWN, AMBALA CITY 134003 Used Since :21/01/2010 DELHI FEED SUPPLIMENTS;PROTEINS FOR VETRINARY PURPOSE;POULTRY FEED SUPPLIMENTS 5877 Trade Marks Journal No: 1842 , 26/03/2018 Class 31 1980030 15/06/2010 KRISHNA CHAURASIA A - 198, GUNJRAWALAN TOWN, PART - 1, DELHI - 110009. MANUFACTURER TRADERS AND SERVICES PROVIDER AN INDIAN NATIONAL Address for service in India/Agents address: THE ACME COMPANY B-41, NIZAMUDDIN EAST, NEW DELHI - 110013. Used Since :13/04/2002 DELHI BETAL SPICES (PAN MASALA), SCENTED & SWEET MOUTH FRESHNERS GOODS FALLING IN CLASS 31. 5878 Trade Marks Journal No: 1842 , 26/03/2018 Class 31 2126091 06/04/2011 INDIAN HERBS SPECIALITIES PRIVATE LIMITED D-21 SHOP NO 2, ACHARYA NIKETAN MAYUR VIHAR, PHASE-I, NEW DELHI-110091 MANUFACTURER AND MERCHANT Address for service in India/Attorney address: KRISHNAMURTHY & CO. -

Current Population Survey, July 2018: Tobacco Use Supplement File That Becomes Available After the File Is Released

CURRENT POPULATION SURVEY, July 2018 Tobacco Use Supplement FILE Version 2, Revised September 2020 TECHNICAL DOCUMENTATION CPS—18 This file documentation consists of the following materials: Attachment 1 Abstract Attachment 2 Overview - Current Population Survey Attachment 3a Overview – July 2018 Tobacco Use Supplement Attachment 3b Overview-Tobacco Use Supplement NCI Data Harmonization Project Attachment 4 Glossary Attachment 5 How to Use the Record Layout Attachment 6 Basic CPS Record Layout Attachment 7 Current Population Survey, July 2018 Tobacco Use Supplement Record Layout Attachment 8 Current Population Survey, July 2018 Tobacco Use Supplement Questionnaire Attachment 9 Industry Classification Codes Attachment 10 Occupation Classification Codes Attachment 11 Specific Metropolitan Identifiers Attachment 12 Topcoding of Usual Hourly Earnings Attachment 13 Tallies of Unweighted Counts Attachment 14 Countries and Areas of the World Attachment 15 Allocation Flags Attachment 16 Source and Accuracy of the July 2018 Tobacco Use Supplement Data Attachment 17 User Notes NOTE Questions about accompanying documentation should be directed to Center for New Media and Promotions Division, Promotions Branch, Bureau of the Census, Washington, D.C. 20233. Phone: (301) 763-4400. Questions about the CD-ROM should be directed to The Customer Service Center, Bureau of the Census, Washington, D.C. 20233. Phone: (301) 763-INFO (4636). Questions about the design, data collection, and CPS-specific subject matter should be directed to Tim Marshall, Demographic Surveys Division, Bureau of the Census, Washington, D.C. 20233. Phone: (301) 763-3806. Questions about the TUS subject matter should be directed to the National Cancer Institute’s Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, Behavior Research Program at [email protected] ABSTRACT The National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the U.S. -

Participating Manfacturers' Brands Approved for Sale

Participating Manufacturers' Brands Brand Family Brand Code Manufacturer 1839 000270 PREMIER MANUFACTURING, INC. 1839 (RYO) 000271 PREMIER MANUFACTURING, INC. 1ST CLASS 000171 PREMIER MANUFACTURING, INC. ACE 000080 KING MAKER MARKETING INC AMERICAN BISON 000292 WIND RIVER TOBACCO COMPANY LLC AMERICAN BISON (RYO) 000293 WIND RIVER TOBACCO COMPANY LLC BALI SHAG (RYO) 000013 TOP TOBACCO LP BARON AMERICAN BLEND 000064 FARMERS TOBACCO CO OF CYNTHIANA INC BASIC 000149 PHILIP MORRIS USA INC BENSON & HEDGES 000150 PHILIP MORRIS USA INC BLACK & GOLD 000227 SHERMANS 1400 BROADWAY NYC LTD BUGLER (RYO) 000595 SCANDINAVIAN TOBACCO GROUP LANE LIMITED CAMBRIDGE 000152 PHILIP MORRIS USA INC CAMEL 000185 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY CAMEL WIDES 000186 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY CANOE (RYO) 000294 WIND RIVER TOBACCO COMPANY LLC CAPRI 000187 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY CARLTON 000188 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY CHECKERS 000081 KING MAKER MARKETING INC CHESTERFIELD 000154 PHILIP MORRIS USA INC CIGARETTELLOS 000228 SHERMANS 1400 BROADWAY NYC LTD CLASSIC 000229 SHERMANS 1400 BROADWAY NYC LTD CROWNS 000593 COMMONWEALTH BRANDS INC CUSTOM BLENDS (RYO) 000295 WIND RIVER TOBACCO COMPANY LLC DAVE'S 000620 PHILIP MORRIS USA INC DAVIDOFF 000014 COMMONWEALTH BRANDS INC DORAL 000189 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY DREAMS 000628 KRETEK INTERNATIONAL INC. July 26, 2021 Page 1 of 4 Brand Family Brand Code Manufacturer DRUM (RYO) 000260 TOP TOBACCO LP DUNHILL 000190 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY DUNHILL INTERNATIONAL 000191 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY EAGLE 20'S 000277 VECTOR TOBACCO INC D/B/A MEDALLION BRANDS ECLIPSE 000192 R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY EVE 000105 LIGGETT GROUP LLC FANTASIA 000230 SHERMANS 1400 BROADWAY NYC LTD FORTUNA 000015 COMMONWEALTH BRANDS INC GAMBLER (RYO) 000261 TOP TOBACCO LP GAULOISES 000016 COMMONWEALTH BRANDS INC GITANES 000017 COMMONWEALTH BRANDS INC GOLD CREST 000083 KING MAKER MARKETING INC GPC 000194 R.J. -

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 11/20/09

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 11/20/09 Beginning August 1, 2008, only the cigarette brands and styles listed below are allowed to be imported, stamped and/or sold in the State of Alaska. Per AS 18.74, these brands must be marked as fire safe on the packaging. The brand styles listed below have been certified as fire safe by the State Fire Marshall, bear the "FSC" marking. There is an exception to these requirements. The new fire safe law allows for the sale of cigarettes that are not fire safe and do not have the "FSC" marking as long as they were stamped and in the State of Alaska before August 1, 2008 and found on the "Directory of MSA Compliant Cigarette & RYO Brands." Filter/ Non- Brand Style Length Circ. Filter Pkg. Descr. Manufacturer 1839 Full Flavor 82.7 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 97 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 83 24.60 Non-Filter Soft Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 83 24.40 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 83 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol Light 83 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. -

The P53 Tumour Suppressor Gene and the Tobacco Industry

Lancet Manuscript 03ART/3495 Revised 1 The p53 Tumor Suppressor Gene and the Tobacco Industry: Research, Debate, and Conflict of Interest Asaf Bitton, BA Mark D. Neuman, BA Joaquin Barnoya, MD MPH Stanton A. Glantz, PhD Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education University of California, San Francisco San Francisco, CA 94143 This work was supported by National Cancer Institute Grant CA-87472 and the American Legacy Foundation. Address for correspondence and Reprints: Stanton A. Glantz, PhD Professor of Medicine Box 1390 University of California San Francisco, CA 94143 415-476-3893 fax 415-514-9345 [email protected] Lancet Manuscript 03ART/3495 Revised 2 Summary Background: Mutations in the p53 tumor suppressor gene lead to uncontrolled cell division and are found in over 50% of all human tumors, including 60% of lung cancers. Research published in 1996 by Mikhail Denissenko et al. demonstrated patterned in vitro mutagenic effects on p53 of benzo[a]pyrene, a carcinogen present in tobacco smoke. We investigate the tobacco industry’s strategies in responding to p53 research linking smoking to cancer. Methods: We searched online tobacco document archives, including the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library and Tobacco Documents Online, and archives maintained by tobacco companies such as Philip Morris and RJ Reynolds. Documents were also obtained from the British American Tobacco Company depository near Guildford, England. Informal correspondence was carried out with scientists, lawyers, and tobacco control experts in the United States and Europe. Findings: Individuals at the highest levels of the tobacco industry anticipated and carefully monitored p53 research. Tobacco scientists conducted research intended to cast doubt on the link between smoking and p53 mutations. -

Cigarettes and Tobacco Products Removed from the California Tobacco Directory by Brand

Cigarettes and Tobacco Products Removed From The California Tobacco Directory by Brand Brand Manufacturer Date Comments Removed #117 - RYO National Tobacco Company 10/21/2011 5/6/05 Man. Change from RBJ to National Tobacco Company 10/20's (ten-twenty's) M/s Dhanraj International 2/6/2012 2/2/05 Man. Name change from Dhanraj Imports, Inc. 10/20's (ten-twenty's) - RYO M/s Dhanraj International 2/6/2012 1st Choice R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company 5/3/2010 Removed 5/2/08; Reinstated 7/11/08 32 Degrees General Tobacco 2/28/2010 4 Aces - RYO Top Tobacco, LP 11/12/2010 A Touch of Clove Sherman 1400 Broadway N.Y.C. Inc. 9/25/2009 AB Rimboche' - RYO Daughters & Ryan, Inc. 6/18/2010 Ace King Maker Marketing 5/21/2020 All American Value Philip Morris, USA 5/5/2006 All Star Liberty Brands, LLC 5/5/2006 Alpine Philip Morris, USA 8/14/2013 Removed 5/4/07; Reinstated 5/8/09 Always Save Liberty Brands, LLC 5/4/2007 American R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company 5/6/2005 American Bison Wind River Tobacco Company, LLC 9/22/2015 American Blend Mac Baren Tobacco Company 5/4/2007 American Harvest Sandia Tobacco Manufacturers, Inc. 8/31/2016 American Harvest - RYO Truth & Liberty Manufacturing 8/2/2016 American Liberty Les Tabacs Spokan 5/12/2006 Amphora - RYO Top Tobacco, LP 11/18/2011 Andron's Passion VCT 5/4/2007 Andron's Passion VCT 5/4/2007 Arango Sportsman - RYO Daughters & Ryan, Inc. 6/18/2010 Arbo - RYO VCT 5/4/2007 Ashford Von Eicken Group 5/8/2009 Ashford - RYO Von Eicken Group 12/23/2011 Athey (Old Timer's) Daughters & Ryan, Inc. -

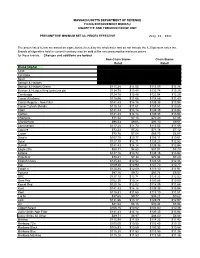

Cigarette Minimum Retail Price List

MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE FILING ENFORCEMENT BUREAU CIGARETTE AND TOBACCO EXCISE UNIT PRESUMPTIVE MINIMUM RETAIL PRICES EFFECTIVE July 26, 2021 The prices listed below are based on cigarettes delivered by the wholesaler and do not include the 6.25 percent sales tax. Brands of cigarettes held in current inventory may be sold at the new presumptive minimum prices for those brands. Changes and additions are bolded. Non-Chain Stores Chain Stores Retail Retail Brand (Alpha) Carton Pack Carton Pack 1839 $86.64 $8.66 $85.38 $8.54 1st Class $71.49 $7.15 $70.44 $7.04 Basic $122.21 $12.22 $120.41 $12.04 Benson & Hedges $136.55 $13.66 $134.54 $13.45 Benson & Hedges Green $115.28 $11.53 $113.59 $11.36 Benson & Hedges King (princess pk) $134.75 $13.48 $132.78 $13.28 Cambridge $124.78 $12.48 $122.94 $12.29 Camel All others $116.56 $11.66 $114.85 $11.49 Camel Regular - Non Filter $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Camel Turkish Blends $110.14 $11.01 $108.51 $10.85 Capri $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Carlton $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Checkers $71.54 $7.15 $70.49 $7.05 Chesterfield $96.53 $9.65 $95.10 $9.51 Commander $117.28 $11.73 $115.55 $11.56 Couture $72.23 $7.22 $71.16 $7.12 Crown $70.76 $7.08 $69.73 $6.97 Dave's $107.70 $10.77 $106.11 $10.61 Doral $127.10 $12.71 $125.23 $12.52 Dunhill $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Eagle 20's $88.31 $8.83 $87.01 $8.70 Eclipse $137.16 $13.72 $135.15 $13.52 Edgefield $73.41 $7.34 $72.34 $7.23 English Ovals $125.44 $12.54 $123.59 $12.36 Eve $109.30 $10.93 $107.70 $10.77 Export A $120.88 $12.09 $119.10 $11.91 -

A Frank Statement to Cigarette Smokers 1

1 A FRANK STATEMENT TO CIGARETTE SMOKERS Recent reports on experiments with mice have given wide publicity to the theory that cigarette smoking is in some way linked with lung cancer in human beings. Although conducted by doctors of professional standing, these experiments are not regarded as conclusive in the field of cancer research. However, we do not believe that any serious medical research, even though its results are inconclusive, should be disregarded or lightly dismissed. At the same time, we feel it is in the public interest to call attention to the fact that eminent doctors and research scientists have publicly questioned the claimed significance of these experiments. Distinguished authorities point out: 1. That medical research of recent years indicates many possible causes of lung cancer. 2. That there is no agreement among the authorities regarding what the cause is. 3. That there is no proof that cigarette smoking is one of the causes. 4. That statistics purporting to link cigarette smoking with the disease could apply with equal force to any one of many other aspects of modern life. Indeed, the validity of the statistics themselves is questioned by numerous scientists. We accept an interest in people’s health as a basic responsibility, paramount to every other consideration in our business. We believe the products we make are not injurious to health. We always have and always will cooperate closely with those whose task it is to safeguard the public health. For more than 300 years tobacco has given solace, relaxation and enjoyment to mankind. At one time or another during those years critics have held it responsible for practically every disease of the human body. -

A Comparison of Smoking Cessation Methods in Normal Smokers and Smokers with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Mary Beth Mueller University of Nebraska-Lincoln

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Open-Access* Master's Theses from the University Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln of Nebraska-Lincoln 5-1990 A Comparison of Smoking Cessation Methods in Normal Smokers and Smokers with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Mary Beth Mueller University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/opentheses Part of the Health and Physical Education Commons, Medical Education Commons, and the Public Health Education and Promotion Commons Mueller, Mary Beth, "A Comparison of Smoking Cessation Methods in Normal Smokers and Smokers with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease" (1990). Open-Access* Master's Theses from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. 12. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/opentheses/12 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open-Access* Master's Theses from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. A COMPARISON OF SMOKING CESSATION METHODS IN NORMAL SMOKERS AND SMOKERS WITH CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE by Mary Beth Mueller A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College in the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for the Degree of Master of Education Major: Health, Physical Education and Recreation Under the Supervision of Professor Gary L. Martin Lincoln, Nebraska May 1990 A COMPARISON OF THREE SMOKING CESSATION TREATMENT METHODS IN NORMAL SMOKERS AND CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE Mary Beth Mueller, M.Ed. University of Nebraska, 1990 Adviser: Gary L. -

Tobacco Control

TOBACCO CONTROL Playbook World Health Organization ABSTRACT Tobacco control is difficult and complex and obstructed by the tactics of the tobacco industry and its allies to oppose effective tobacco control measures. This document was developed by the WHO Regional Office for Europe by collecting numerous evidence-based arguments from different thematic areas, reflecting the challenges that tobacco control leaders have faced while implementing various articles of the WHO FCTC and highlighting arguments they have developed in order to counter and succeed against the tobacco industry. KEY WORDS TOBACCO CONTROL WHO FCTC HEALTH EFFECTS TOBACCO INDUSTRY ARGUMENTS © World Health Organization 2019 All rights reserved. The Regional Office for Europe of the World Health Organization welcomes requests for permission to reproduce or translate its publications, in part or in full. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. -

Amicus Curiae Public Health Advocacy Institute in Support of Appellants

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS SUPREME JUDICIAL COURT FOR THE COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS No. SJC-11641 ___________________________ STEVEN P. ABDOW, STEPHANIE C. CRIMMONS, JOSEPH A. CURATONE, GERI EDDINS, MARK A. GOTTLIEB, CELESTE B. MEYERS, KRISTIAN M. MINEAU, KATHLEEN CONLEY NORBUT, JOHN F. RIBEIRO, and SUSAN C. TUCKER, Plaintiffs/Appellants v. GEORGE DUCHARME, ET AL., DANIEL RIZZO, ET AL., and DOMENIC J. SARNO, ET AL., Interveners/Appellants, v. ATTORNEY GENERAL and SECRETARY OF THE COMMONWEALTH, Defendants/Appellees. ___________________________ BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE PUBLIC HEALTH ADVOCACY INSTITUTE IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS ___________________________ Edward L. Sweda, Jr. BBO #489820 Public Health Advocacy Institute 360 Huntington Ave., 117 CU Boston, MA 02115 (617) 373-2026 Counsel for the Public Health Advocacy Institute TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES................................ ii CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT....................... 1 STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF THE AMICI CURIAE............ 1 INTRODUCTION......................................... 2 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.................................. 4 ARGUMENT............................................. 6 CONCLUSION.......................................... 42 CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE WITH MASS. R. APP. P. 16(k) .................................................... 44 i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Cases Aspinall v. Philip Morris Cos., Inc., 2014 Mass. Super. LEXIS 26 (Mass. 2014) ....................................................... 15 Donovan v. Philip Morris USA, Inc., -

Brand Families Approved for Stamping Or Sale in Montana As of June 25, 2012

MONTANA DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE Brand Families Approved for Stamping or Sale in Montana as of June 25, 2012 You may not sell cigarettes listed in this Tobacco Directory unless a minimum price has been established by the Department of Revenue. PM: Participating Manufacturer NPM: Non-Participating Manufacturer # A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z BRAND FAMILY MANUFACTURER PM or NPM # Top 1839 U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. PM 1839 RYO U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. PM A Top Ace King Maker Marketing Inc. PM Alpine Philip Morris USA Inc. PM American Bison Wind River Tobacco Company, LLC PM American Bison RYO Wind River Tobacco Company, LLC PM American Harvest RYO Truth and Liberty Manufacturing Co. NPM Austin R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company PM B Top Bali Shag RYO Imperial Tobacco Limited (United Kingdom) PM Baron American Blend Farmer’s Tobacco Company of Cynthiana, Inc. PM Basic Philip Morris USA Inc. PM Benson & Hedges Philip Morris USA Inc. PM Black & Gold Sherman’s 1400 Broadway NYC Ltd. PM Bo Browning RYO Top Tobacco, L.P. PM Bristol Philip Morris USA Inc. PM Bugler RYO Scandinavian Tobacco Group Lane Limited PM C Top Cambridge Philip Morris USA Inc. PM Camel R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company PM Camel Wides R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company PM Canoe RYO Wind River Tobacco Company, LLC PM Capri R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company PM Montana Department of Justice Brand Families Approved for Stamping Page 1 of 6 or Sale in Montana as of June 25, 2012 BRAND FAMILY MANUFACTURER PM or NPM Carlton R.J.