Sudduth Colostate 0053N 11131

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mild to Moderately Severe

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2011 Mild To Moderately Severe J D. Valencia University of Central Florida Part of the Creative Writing Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Valencia, J D., "Mild To Moderately Severe" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 1985. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/1985 MILD TO MODERATELY SEVERE by J DANIEL VALENCIA BA University of Central Florida, 2007 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Department of English in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2011 © 2011 J Daniel Valencia ii ABSTRACT Mild to Moderately Severe is an episodic memoir of a boy coming of age as a latch-key kid, living with a working single mother and partly raising himself, as a hearing impaired and depressed young adult, learning to navigate the culture with a strategy of faking it, as a nomad with seven mailing addresses before turning ten. It is an examination of accidental and cultivated loneliness, a narrative of a boy and later a man who is too adept at adapting to different environments, a reflection on relationships and popularity and a need for attention and love that clashes with a need to walk through unfamiliar neighborhoods alone. -

{Download PDF} the Stars Are Right Ebook Free Download

THE STARS ARE RIGHT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Chaosium RPG Team | 180 pages | 14 May 2008 | CHAOSIUM INC | 9781568821771 | English | Hayward, United States The Stars are Right PDF Book Photo Courtesy: P! Natalie Dormer and Gene Tierney With HBO's massively successful fantasy series Game of Thrones finally over and a whole slew of spinoff series coming down the pipeline soon enough , many fans of the show are left wondering what star Natalie Dormer will do next. For instance, they've starred in the Ocean's film series and Burn After Reading. Here's What to Expect for the Super Bowl. It can't be denied that everyone knows her name. It can sometimes feel like society has hit a new level of boy craziness sometimes. Lea Michele and Naya Rivera The cast of Glee was riddled with as much in-house drama as a real-life glee club. When Lea Michele started gaining a massive fanbase, other characters started receiving fewer lines and less-important storylines. If more than one person in your household wants to vote, each person will need to create a personal ABC account. More than one person can use the same computer or device to vote, but each person needs to log out after voting. The achievement or service doesn't involve participation in aerial flight, and it can occur during engagement against a U. As such, it must be said that both these two stars deserve far more praise than they typically receive. As it turns out, the coffee business didn't quite work out. -

Anne Raduns Divorce Guide

(888) 740-5140 221 Northwest 4th Street, Ocala, FL 34475 [email protected] www.ocalafamilylaw.com (888) 740-5140 www.ocalafamilylaw.com Caring and Aggressive Legal Representa on “Protecting your interests and helping you make it successfully through your divorce is not just my profession — it’s my passion!” Anne E. Raduns, PA Your Skilled, Trusted and Compassionate Coach Focused on a Fair Resolution — but Ready to During Divorce Aggressively Litigate During divorce, you'll be faced with decisions that aff ect the The ideal strategy to pursue during divorce is one that rest of your life. And that's why during this stressful me, you achieves a fair and equitable se lement — and avoids me need more than a capable family lawyer — you also need consuming, stressful, and costly li ga on. Anne strives to an experienced, caring and forward-looking coach who will work with the other family lawyer to achieve an op mal help you move ahead with your life. At the Ocala, Florida se lement. However, when this approach is not in your law fi rm of Anne E. Raduns, PA, experienced Family Lawyer best interest or not possible given the circumstances of your Anne Raduns is both the skilled divorce lawyer and dedicated unique issues, be assured that Anne has the in-depth legal counsellor of law you need. Having prac ced exclusively in knowledge, confidence, and experience to aggressively rep- family law for many years, Anne will guide, mo vate, advo- resent you in court and protect your interests. cate and zealously protect you and your family's interests. -

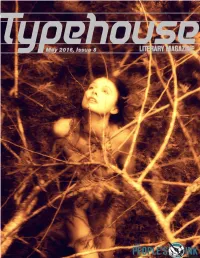

1 Typehouse Literary Magazine Issue 8, May 2016 2 Call for Submissions

1 Typehouse Literary Magazine Issue 8, May 2016 2 Call for Submissions Typehouse is a writer-run, literary magazine based out of Portland, Oregon. We publish non-fiction, genre fiction, literary fiction, poetry and visual art. We are always looking for well-crafted, previously unpublished, writing that seeks to capture an awareness of the human predicament. f you are interested in submitting fiction, poetry, or visual art, email your submission as an attachment or within the body of the email along with a short bio to: typehouse"peoples-ink.com Editors #al $ryphin %indsay &owler Michael Munkvold Cover Photo Pastoral: &ae ( by ). *iding and +. %a &ey ,+ee page -./ 0stablished (123 Published Triennially http!44typehousemagazine.com4 3 Typehouse Literary Magazine Table of Contents: Fiction: 5unky Town 5aley '. &edor 6 +tall $. ). +hepard 27 The )lpine 'all )manda McTigue 33 ) 'arvel of 'odern +cience $eorge )llen Miller 61 n the Wine-8ark 8eep +haun 9ossio 66 *eturned &ire :. 0dward ;ruft << +hampoo +amantha Pilecki -< )lchemy ;athryn %ipari -- Poetry: William Ogden 5aynes (< *achael )dams =6 +teve %uria )blon 63 *obert 9rown <- Visual Art: Tagen T. 9aker 26 >assandra +ims ;night 32 &abrice 9. Poussin =. ). *iding <( 8enny 0. Marshall 211 Issue 8, May 2016 4 Haley Fedor is a queer author from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Section 8 Magazine, The Fem, Guide to Kulchur Magazine, Literary Orphans, Crab Fat Literary Magazine, and the anthology Dispatches from Lesbian America. She was nominated for the 2014 Pushcart Prize, and is currently a graduate student at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. Hunky Town Haley M Fedor The car went ?uickly over a bump, and Michael hit his head on the lid of the trunk. -

Cedars, November 16, 2001 Cedarville University

Masthead Logo Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Cedars 11-16-2001 Cedars, November 16, 2001 Cedarville University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/cedars Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Organizational Communication Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a platform for archiving the scholarly, creative, and historical record of Cedarville University. The views, opinions, and sentiments expressed in the articles published in the university’s student newspaper, Cedars (formerly Whispering Cedars), do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The uthora s of, and those interviewed for, the articles in this paper are solely responsible for the content of those articles. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Cedarville University, "Cedars, November 16, 2001" (2001). Cedars. 55. https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/cedars/55 This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Footer Logo DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cedars by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Cedarville University Student Publication cedars Volume 50, Issue 4 November 16, 2001 Women Runners Claim NCCAA Championship Sandra Wilhelm wanted to win, and that is ex- to nationals and see what -

Hegel 250—Too Late?

HEGEL 250—TOO LATE? Ljubljana 2020 HEGEL 250—TOO LATE? ANALECTA Publisher: Društvo za teoretsko psihoanalizo Publishing board: Miran Božovič, Mladen Dolar, Rado Riha, Alenka Zupančič (president), Slavoj Žižek Edited by Mladen Dolar Copyedited by Tanja Dominko and Eric Powell Cover Design by AOOA Layout by Klemen Ulčakar Printed by Ulčakar Grafika First Edition Circulation 200 Ljubljana 2020 This publication has been co-published in partnership with the Goethe-Institut Ljubljana. CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 1Hegel G.W.F.(082) HEGEL 250 - too late? / [edited by Mladen Dolar]. - 1st ed. - Ljubljana : Društvo za teoretsko psihoanalizo : Goethe-Institut, 2020. - (Zbirka Analecta) (Problemi ; let. 58, 11-12) (Problemi International ; 2020, 4) ISBN 978-961-6376-94-5 (Društvo za teoretsko psihoanalizo) COBISS.SI-ID 61238531 Table of Contents Hegel Reborn: A Brief Introduction to HEGEL 250—TOO LATE? Árpád-Andreas Sölter. 5 Hegel’s Time! Ana Jovanović, Bara Kolenc, Urban Šrimpf, Goran Vranešević. 9 Nadia Bou Ali and Ray Brassier After Too Late: The Endgame of Analysis. 11 Mladen Dolar What’s the Time? On Being Too Early or Too Late in Hegel’s Philosophy. 31 Luca Illetteratti Nature’s Externality: Hegel’s Non-Naturalistic Naturalism. .51 Zdravko Kobe The Time of Philosophy: On Hegel’s Conception of Modern Philosophy . 73 Bara Kolenc Is It Too Late?. 91 Christian Krijnen “What, if Anything, Has Not Been Called Philosophizing?” On the Relevance of Hegel’s Conception of a Philosophical History of Philosophy. 119 Gregor Moder What Is To Be Done: On the Theatricality of Power. 143 Nadia Bou Ali and Ray Brassier Sebastian Rödl Thinking Nothing . -

Contractors Continue KY-121 Construction CCHS Earns Highest

THEOur Vision: “Successful-LAKER Now and Beyond” REVIEWOur Mission: “Learners for Life” Volume 36 Calloway County High School Issue 2 2108 College Farm Road, Murray, Ky. 42071 November 4, 2016 Homecoming Queen CCHS earns highest rank in testing Braxton Bogard vested interest in students’ lives of the distinguished rating. Wil- Editor in Chief that goes beyond the classroom. murth also reported that a district- “We’re pleased and excited wide ranking of distinguished was CCHS was named a progress- because our students had to do a earned, which it has held for the ing distinguished school based on good job, but the biggest challenge past three years. test results from the Kentucky is just continuing to have good “CCHS is once again one of Performance Rating for Educa- staff members like we have. What the top schools, not only in West tional Progress (K-PREP). I have found, generally, is that our Kentucky, but also the entire Principal Randy McCallon staff members are also interested Commonwealth,” he said. spoke about the recent success. in helping and sponsoring clubs CCHS English teacher Steve “We surpassed our goal as far that are motivating, taking kids Smith commented on CCHS as the minimum goal we needed to competitions, volunteering to sophomores’ and juniors’ success to put us in the category in or- help with prom and homecoming on the on-demand writing portion der to be a school of distinction, dances, and helping sponsor the of the exam. but, secondly, we met what they various things we do.” “I can say that the state of Ken- call annual measurable objectives, McCallon said that the qual- tucky has placed an enormous which generally are subgroups of ity of instruction from teachers, emphasis on writing over the past populations of students and how good student relations and parents 25 years. -

Tale of the Tape Wright State Vs. Manhattan

WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STATE RAIDERS • WRIGHT STAT Game 33 Wright State vs. Manhattan Wright State Nutter Center March 20, 2011 2010-11 SCHEDULE/RESULTS November (2-2, 0-0 HL) 12 at IUPUI W 64-45 Overall Record 20-12 23-9 14 at Ball State L 63-64 Conference Record 11-7 13-5 21 at Delaware State W 58-52 Points Per Game 67.9 56.8 Opponent Points Per Game 67.0 49.8 29 DAYTON L 61-91 Rebounds Per Game 43.0 32.4 Opponent Rebounds Per Game 38.1 35.7 December (6-2, 1-0 HL) Field Goal Percentage .403 .379 Opponent Field Goal Percentage .378 .361 1 MIAMI L 57-62 Three-Point Percentage .301 .346 4 at Akron W 71-64 Opponent Three-Point Percentage .333 .310 9 at Ohio W 70-57 Free Throw Percentage .687 .725 11 at Longwood L 70-74 Tale of the Tape Fouls 462 428 Opponent Fouls 507 480 14 at Southern Illinois W 75-53 Assists 403 382 18 at Cincinnati W 65-50 Turnovers 554 491 22 CENTRAL FLORIDA W 73-65 Blocked Shots 58 86 Wright State vs. Manhattan 31 at Milwaukee * W 77-73 Steals 199 365 January (5-3, 5-3 HL) (projected starters) Tippin’ Off 2 at #21 Green Bay * L 57-75 #3 LaShawna Thomas 5-6 Sr. -

Parenting After Separation (PAS) Parent's Guide

Parenting After Separation (PAS) Parent’s Guide Family Justice Services Parenting After Separation Program page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Parenting Plan Outline . 9 Section 1 — Relationship Building Blocks Attachment and Relationships . 11 Healthy Parenting . 12 Healthy Co-parenting . 14 Keeping Both Parents Involved . 16 FAQs about Relationship Building . 17 Handout — Recognizing High Conflict Coparental Relationships . 21 Handout — Recognizing Abusive Relationships . 22 Parenting Plan Reflective Questions — Relationships . 24 Section 2 — Children Can Cope with Separation and Divorce Effects of Parental Separation or Divorce on Children . 25 Ways to Promote Positive Coping . 28 FAQs about Promoting Coping . 31 Handout — Recognizing your Child’s Temperament . 35 Handout — Age-by-Age Guideline: Children’s Reactions and How to Help . 38 Parenting Plan Reflective Questions — Children . 46 Section 3 — Learning your Way Around the Legal System The Divorce Process and Legal Terminology . 47 Dispute Resolution Process . 50 FAQs about Legal Process . 51 Handout — Steps in the Court Process . 55 Handout — Dispute Resolution Processes . 56 Parenting Plan Reflective Questions- Legal Issues . 59 Contents Contents Section 4 — Parenting Plans that Work for Your Family What is a Parenting Plan . 61 Parts of a Parenting Plan . 61 One Way to Develop a Parenting Plan . 63 Parenting Arrangements . 64 Giving Children a Say . 65 FAQs — Parenting Plans . 66 Parenting Plan Reflective Questions — parenting plans . 71 Handout — Preparing For Your Parenting Plan . 72 Handout — Parenting Plan Worksheet . 81 Important Information Whom to Call . 98 Telling Your child about the Separation or Divorce . 102 Building Resilience in Children . 104 Building Better Brains . 107 Court Process Flow Chart . 108 You and Your Family Law Lawyer . -

Family Jewels

Family Jewels Kate Christie Copyright © 2012 by Kate Christie Second Growth Books Seattle, WA All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, without permission in writing from the author. Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper First published 2012 Cover Design: Kate Christie ISBN: 0985367717 ISBN-13: 978-0985367718 DEDICATION To our newest players to be named later: We’re all waiting to meet you! No pressure. Really. Love, Mama, Mimi, Alex, Maggie, & Corona CHAPTER ONE The year everything changed seemed to start out happily enough. I rang in the new year with Dez, my best friend since Women’s Studies 101 freshman year at University of Michigan, and Maddie, my girlfriend of two and a half years who I was thinking of asking to move in with me on Valentine’s Day. We stood together on the deck at another friend’s party in downtown Ann Arbor, my arms looped around each of their necks, humming along to “Auld Lang Syne” and shivering as we watched fireworks light up the clear, unusually snow- free sky. None of us knew the words to the penultimate New Year’s Eve tune, but that didn’t matter. Sure, I was another year closer to thirty without having accomplished much that other people—my family, specifically—would consider significant. But I had a pair of jobs that I liked, my best buddy at my side, and a future planned with the woman I loved. -

Glee Cast Dont Speak

Glee cast dont speak click here to download Don't Speak Lyrics: You and me / We used to be together / Everyday together / Always / I really feel / That I'm losing my best friend / I can't believe this could be. Lyrics to "Don't Speak" song by Glee Cast: You and me We used to be together Everyday together Always I really feel That I'm losing my be. Lyrics to 'Don't Speak' by Glee Cast. You and me / We used to be together / Everyday together always / I really feel / That I'm losing my best friend / I can't. This week's episode of Glee is called “The Break-Up” and in it, the cast takes on a host of split-up songs. One is the No Doubt hit “Don't Speak,”. Don't Speak Songtext von Glee Cast mit Lyrics, deutscher Übersetzung, Musik- Videos und Liedtexten kostenlos auf www.doorway.ru When Glee aired its first episode in May , the TV show only attracted a fraction of the viewers who tuned in for American Idol, which was. Don't Speak (Glee Cast Version). By Glee Cast. • 1 song. Play on Spotify. 1. Don't Speak (Glee Cast Version). Check out Don't Speak (Glee Cast Version) by Glee Cast on Amazon Music. Stream ad-free or purchase CD's and MP3s now on www.doorway.ru Stream Don't Speak - Glee cast by Jesse Camron from desktop or your mobile device. Finn: You and me. We used to be together. Everyday together. Always Blaine: I really feel. -

Henryviii Program FINAL Lores.Pdf

b1737_HENR_Program.indd 1 4/23/13 5:22 PM —The Two Gentlemen of Verona, Act I, Scene iii b1737_HENR_Program.indd 2 4/23/13 5:22 PM HENRY VIII Contents Chicago Shakespeare Theater 800 E. Grand on Navy Pier On the Boards 8 Chicago, Illinois 60611 A selection of notable CST 312.595.5600 events, plays and players www.chicagoshakes.com ©2013 Chicago Shakespeare Theater Point of View 12 All rights reserved. Artistic Director Barbara Gaines discusses her first staging of ARTISTIC DIRECTOR: Barbara Gaines EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Criss Henderson Shakespeare’s late play PICTURED, COVER AND ABOVE: Gregory Wooddell and Christina Pumariega, Cast 19 photos by Bill Burlingham Playgoer’s Guide 20 Profiles 22 Scholar’s Notes 32 Scholar Stuart Sherman explores the elasticity of truth in Shakespeare’s Henry VIII www.chicagoshakes.com 3 b1737_HENR_Program.indd 3 4/23/13 5:22 PM unforgettable . Hyatt is proud to sponsor Chicago Shakespeare Theater. We’ve supported the theater since its inception and believe one unforgettable performance deserves another. Experience distinctive design, extraordinary service and award-winning cuisine at every Hyatt worldwide. For reservations, call or visit hyatt.com. HYATT name, design and related marks are trademarks of Hyatt Corporation. ©2012 Hyatt Corporation. All rights reserved. HCM29411.01.a_Shakespeare_Ad.indd 1 1/26/12 10:24 AM b1737_HENR_Program.indd 4 4/23/13 5:22 PM A MESSAGE FROM Barbara Gaines Criss Henderson Raymond F. McCaskey Artistic Director Executive Director Chair, Board of Directors DEAR FRIENDS Henry VIII was certainly a notorious king, but ironically Shakespeare’s work bearing his name is not often produced.