Family Jewels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mild to Moderately Severe

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2011 Mild To Moderately Severe J D. Valencia University of Central Florida Part of the Creative Writing Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Valencia, J D., "Mild To Moderately Severe" (2011). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 1985. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/1985 MILD TO MODERATELY SEVERE by J DANIEL VALENCIA BA University of Central Florida, 2007 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in the Department of English in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2011 © 2011 J Daniel Valencia ii ABSTRACT Mild to Moderately Severe is an episodic memoir of a boy coming of age as a latch-key kid, living with a working single mother and partly raising himself, as a hearing impaired and depressed young adult, learning to navigate the culture with a strategy of faking it, as a nomad with seven mailing addresses before turning ten. It is an examination of accidental and cultivated loneliness, a narrative of a boy and later a man who is too adept at adapting to different environments, a reflection on relationships and popularity and a need for attention and love that clashes with a need to walk through unfamiliar neighborhoods alone. -

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

{Download PDF} the Stars Are Right Ebook Free Download

THE STARS ARE RIGHT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Chaosium RPG Team | 180 pages | 14 May 2008 | CHAOSIUM INC | 9781568821771 | English | Hayward, United States The Stars are Right PDF Book Photo Courtesy: P! Natalie Dormer and Gene Tierney With HBO's massively successful fantasy series Game of Thrones finally over and a whole slew of spinoff series coming down the pipeline soon enough , many fans of the show are left wondering what star Natalie Dormer will do next. For instance, they've starred in the Ocean's film series and Burn After Reading. Here's What to Expect for the Super Bowl. It can't be denied that everyone knows her name. It can sometimes feel like society has hit a new level of boy craziness sometimes. Lea Michele and Naya Rivera The cast of Glee was riddled with as much in-house drama as a real-life glee club. When Lea Michele started gaining a massive fanbase, other characters started receiving fewer lines and less-important storylines. If more than one person in your household wants to vote, each person will need to create a personal ABC account. More than one person can use the same computer or device to vote, but each person needs to log out after voting. The achievement or service doesn't involve participation in aerial flight, and it can occur during engagement against a U. As such, it must be said that both these two stars deserve far more praise than they typically receive. As it turns out, the coffee business didn't quite work out. -

Anne Raduns Divorce Guide

(888) 740-5140 221 Northwest 4th Street, Ocala, FL 34475 [email protected] www.ocalafamilylaw.com (888) 740-5140 www.ocalafamilylaw.com Caring and Aggressive Legal Representa on “Protecting your interests and helping you make it successfully through your divorce is not just my profession — it’s my passion!” Anne E. Raduns, PA Your Skilled, Trusted and Compassionate Coach Focused on a Fair Resolution — but Ready to During Divorce Aggressively Litigate During divorce, you'll be faced with decisions that aff ect the The ideal strategy to pursue during divorce is one that rest of your life. And that's why during this stressful me, you achieves a fair and equitable se lement — and avoids me need more than a capable family lawyer — you also need consuming, stressful, and costly li ga on. Anne strives to an experienced, caring and forward-looking coach who will work with the other family lawyer to achieve an op mal help you move ahead with your life. At the Ocala, Florida se lement. However, when this approach is not in your law fi rm of Anne E. Raduns, PA, experienced Family Lawyer best interest or not possible given the circumstances of your Anne Raduns is both the skilled divorce lawyer and dedicated unique issues, be assured that Anne has the in-depth legal counsellor of law you need. Having prac ced exclusively in knowledge, confidence, and experience to aggressively rep- family law for many years, Anne will guide, mo vate, advo- resent you in court and protect your interests. cate and zealously protect you and your family's interests. -

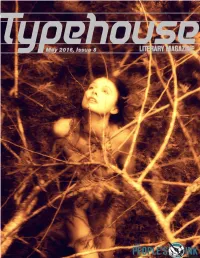

1 Typehouse Literary Magazine Issue 8, May 2016 2 Call for Submissions

1 Typehouse Literary Magazine Issue 8, May 2016 2 Call for Submissions Typehouse is a writer-run, literary magazine based out of Portland, Oregon. We publish non-fiction, genre fiction, literary fiction, poetry and visual art. We are always looking for well-crafted, previously unpublished, writing that seeks to capture an awareness of the human predicament. f you are interested in submitting fiction, poetry, or visual art, email your submission as an attachment or within the body of the email along with a short bio to: typehouse"peoples-ink.com Editors #al $ryphin %indsay &owler Michael Munkvold Cover Photo Pastoral: &ae ( by ). *iding and +. %a &ey ,+ee page -./ 0stablished (123 Published Triennially http!44typehousemagazine.com4 3 Typehouse Literary Magazine Table of Contents: Fiction: 5unky Town 5aley '. &edor 6 +tall $. ). +hepard 27 The )lpine 'all )manda McTigue 33 ) 'arvel of 'odern +cience $eorge )llen Miller 61 n the Wine-8ark 8eep +haun 9ossio 66 *eturned &ire :. 0dward ;ruft << +hampoo +amantha Pilecki -< )lchemy ;athryn %ipari -- Poetry: William Ogden 5aynes (< *achael )dams =6 +teve %uria )blon 63 *obert 9rown <- Visual Art: Tagen T. 9aker 26 >assandra +ims ;night 32 &abrice 9. Poussin =. ). *iding <( 8enny 0. Marshall 211 Issue 8, May 2016 4 Haley Fedor is a queer author from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Section 8 Magazine, The Fem, Guide to Kulchur Magazine, Literary Orphans, Crab Fat Literary Magazine, and the anthology Dispatches from Lesbian America. She was nominated for the 2014 Pushcart Prize, and is currently a graduate student at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. Hunky Town Haley M Fedor The car went ?uickly over a bump, and Michael hit his head on the lid of the trunk. -

Cedars, November 16, 2001 Cedarville University

Masthead Logo Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Cedars 11-16-2001 Cedars, November 16, 2001 Cedarville University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/cedars Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Organizational Communication Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a platform for archiving the scholarly, creative, and historical record of Cedarville University. The views, opinions, and sentiments expressed in the articles published in the university’s student newspaper, Cedars (formerly Whispering Cedars), do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The uthora s of, and those interviewed for, the articles in this paper are solely responsible for the content of those articles. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Cedarville University, "Cedars, November 16, 2001" (2001). Cedars. 55. https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/cedars/55 This Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Footer Logo DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cedars by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Cedarville University Student Publication cedars Volume 50, Issue 4 November 16, 2001 Women Runners Claim NCCAA Championship Sandra Wilhelm wanted to win, and that is ex- to nationals and see what -

Hegel 250—Too Late?

HEGEL 250—TOO LATE? Ljubljana 2020 HEGEL 250—TOO LATE? ANALECTA Publisher: Društvo za teoretsko psihoanalizo Publishing board: Miran Božovič, Mladen Dolar, Rado Riha, Alenka Zupančič (president), Slavoj Žižek Edited by Mladen Dolar Copyedited by Tanja Dominko and Eric Powell Cover Design by AOOA Layout by Klemen Ulčakar Printed by Ulčakar Grafika First Edition Circulation 200 Ljubljana 2020 This publication has been co-published in partnership with the Goethe-Institut Ljubljana. CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana 1Hegel G.W.F.(082) HEGEL 250 - too late? / [edited by Mladen Dolar]. - 1st ed. - Ljubljana : Društvo za teoretsko psihoanalizo : Goethe-Institut, 2020. - (Zbirka Analecta) (Problemi ; let. 58, 11-12) (Problemi International ; 2020, 4) ISBN 978-961-6376-94-5 (Društvo za teoretsko psihoanalizo) COBISS.SI-ID 61238531 Table of Contents Hegel Reborn: A Brief Introduction to HEGEL 250—TOO LATE? Árpád-Andreas Sölter. 5 Hegel’s Time! Ana Jovanović, Bara Kolenc, Urban Šrimpf, Goran Vranešević. 9 Nadia Bou Ali and Ray Brassier After Too Late: The Endgame of Analysis. 11 Mladen Dolar What’s the Time? On Being Too Early or Too Late in Hegel’s Philosophy. 31 Luca Illetteratti Nature’s Externality: Hegel’s Non-Naturalistic Naturalism. .51 Zdravko Kobe The Time of Philosophy: On Hegel’s Conception of Modern Philosophy . 73 Bara Kolenc Is It Too Late?. 91 Christian Krijnen “What, if Anything, Has Not Been Called Philosophizing?” On the Relevance of Hegel’s Conception of a Philosophical History of Philosophy. 119 Gregor Moder What Is To Be Done: On the Theatricality of Power. 143 Nadia Bou Ali and Ray Brassier Sebastian Rödl Thinking Nothing . -

Linda Davis to Matt King

Sound Extreme Entertainment Karaoke Show with Host 828-551-3519 [email protected] www.SoundExtreme.net In The Style Of Title Genre Linda Davis From The Inside Out Country Linda Davis I Took The Torch Out Of His Old Flame Country Linda Davis I Wanna Remember This Country Linda Davis I'm Yours Country Linda Ronstadt Blue Bayou Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt Different Drum Pop Linda Ronstadt Heartbeats Accelerating Country Linda Ronstadt How Do I Make You Pop Linda Ronstadt It's So Easy Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt I've Got A Crush On You Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt Love Is A Rose Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt Silver Threads & Golden Needles Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt That'll Be The Day Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt What's New Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt When Will I Be Loved Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt You're No Good Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville All My Life Pop / Rock Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville Don't Know Much Country & Pop Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville When Something Is Wrong With My Baby Pop Linda Ronstadt & James Ingram Somewhere Out There Pop / Rock Lindsay Lohan Over Pop Lindsay Lohan Rumors Pop / Rock Lindsey Haun Broken Country Lionel Cartwright Like Father Like Son Country Lionel Cartwright Miles & Years Country Lionel Richie All Night Long (All Night) Pop Lionel Richie Angel Pop Lionel Richie Dancing On The Ceiling Country & Pop Lionel Richie Deep River Woman Country & Pop Lionel Richie Do It To Me Pop / Rock Lionel Richie Hello Country & Pop Lionel Richie I Call It Love Pop Sound Extreme Entertainment www.SoundExtreme.net www.SoundExtremeWeddings.com www.CrocodileSmile.net 360 King Rd. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

Contractors Continue KY-121 Construction CCHS Earns Highest

THEOur Vision: “Successful-LAKER Now and Beyond” REVIEWOur Mission: “Learners for Life” Volume 36 Calloway County High School Issue 2 2108 College Farm Road, Murray, Ky. 42071 November 4, 2016 Homecoming Queen CCHS earns highest rank in testing Braxton Bogard vested interest in students’ lives of the distinguished rating. Wil- Editor in Chief that goes beyond the classroom. murth also reported that a district- “We’re pleased and excited wide ranking of distinguished was CCHS was named a progress- because our students had to do a earned, which it has held for the ing distinguished school based on good job, but the biggest challenge past three years. test results from the Kentucky is just continuing to have good “CCHS is once again one of Performance Rating for Educa- staff members like we have. What the top schools, not only in West tional Progress (K-PREP). I have found, generally, is that our Kentucky, but also the entire Principal Randy McCallon staff members are also interested Commonwealth,” he said. spoke about the recent success. in helping and sponsoring clubs CCHS English teacher Steve “We surpassed our goal as far that are motivating, taking kids Smith commented on CCHS as the minimum goal we needed to competitions, volunteering to sophomores’ and juniors’ success to put us in the category in or- help with prom and homecoming on the on-demand writing portion der to be a school of distinction, dances, and helping sponsor the of the exam. but, secondly, we met what they various things we do.” “I can say that the state of Ken- call annual measurable objectives, McCallon said that the qual- tucky has placed an enormous which generally are subgroups of ity of instruction from teachers, emphasis on writing over the past populations of students and how good student relations and parents 25 years. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P.