6 Strategic Positioning and Brand Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No Man's Elizabeth: Frances A. Yates and the History of History! Deanne Williams

12 No Man's Elizabeth: Frances A. Yates and the History of History! Deanne Williams "Shall we lay the blame on the war?" Virginia Woolf, A Room arOne's Own Elizabeth I didn't like women much. She had her female cousin killed, banished married ladies-in-waiting (she had some of them killed, too), and dismissed the powers and potential of half the world's population when she famously addressed the troops at Tilbury, "I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach ~f a king."z Of course, being a woman was a disappointment from the day she was born: it made her less valuable in her parents' and her nation's eyes, it diminished the status of her mother and contributed to her downfall, and it created endless complications for Elizabeth as queen, when she was long underestim ated as the future spouse of any number of foreign princes or opportunistic aristocrats and courtiers. Elizabeth saw from a very early age the precarious path walked by her father's successive wives. Under such circumstances, who would want to be female? Feminist scholars have an easier time with figures such as Marguerite de Navarre, who enjoyed a network of female friends and believed strongly in women's education; Christine de Pisan, who addressed literary misogyny head-on; or Margaret Cavendish, who embodies all our hopes for women and the sciences.3 They allow us to imagine and establish a transhistor ical feminist sisterhood. Elizabeth I, however, forces us to acknowledge the opacity of the past and the unbridgeable distance that divides us from our historical subjects. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOURTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 . 737-4215/842-6353 EXHBITION FACT SHEET Title; THE TREASURE HOUSES OF BRITAIN: FIVE HUNDRED YEARS OF PRIVATE PATRONAGE AND ART COLLECTING Patrons: Their Royal Highnesses The Prince and Princess of Wales Dates; November 3, 1985 through March 16, 1986, exactly one week later than previously announced. (This exhibition will not travel. Loans from houses open to view are expected to remain in place until the late summer of 1985 and to be returned before many of the houses open for their visitors in the spring of 1986.) Credits; This exhibition is made possible by a generous grant from the Ford Motor Company. The exhibition was organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, in collaboration v\n.th the British Council and is supported by indemnities from Her Majesty's Treasury and the U.S. Federal Council on the Arts and Humanities. Further British assistance was supplied by the National Trust and the Historic Houses Association. History of the exhibition; The suggestion that the National Gallery of Art consider holding a major exhibition devoted to British art was made by the British Council in 1979. J. Carter Brown, Director of the National Gallery, responded with the idea of an exhibition on the British Country House as a "vessel of civilization," bringing together works of art illustrating the extraordinary achievement of collecting and patronage throughout Britain over the past five hundred years. As this concept carried with it the additional, contemporary advantage of stimulating greater interest in and support of those houses open to public viewing, it was enthusiastically endorsed by the late Lord Howard of Henderskelfe, then-Chairman of the Historic Houses Association, Julian Andrews, Director of the Fine Arts Department of the British Council, and Lord Gibson, Chairman of the National Trust. -

From Allegory to Domesticity and Informality, Elizabeth I and Elizabeth II

The Image of the Queen; From Allegory to Domesticity and Informality, Elizabeth I and Elizabeth II. By Mihail Vlasiu [Master of Philosophy Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow] Christie’s Education London Master’s Programme September 2000 © Mihail Vlasiu ProQuest Number: 13818866 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818866 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 GLASGOW 1 u n iv er sity .LIBRARY: \1S3lS Abstract This thesis focuses on issues of continuity and change in the evolution royal portraiture and examines the similarities and differences in portraying Elizabeth I in the 16th and 17th centuries and Elizabeth II in the 20th century. The thesis goes beyond the similarity of the shared name of the two monarchs; it shows the major changes not only in the way of portraying a queen but also in the way in which the public has changed its perception of the monarch and of the monarchy. Elizabeth I aimed to unite a nation by focusing the eye upon herself, while Elizabeth II triumphed through humanity and informality. -

ISSUE 2493 | Antiquestradegazette.Com | 22 May 2021 | UK £4.99 | USA $7.95 | Europe €5.50

To print, your print settings should be ‘fit to page size’ or ‘fit to printable area’ or similar. Problems? See our guide: https://atg.news/2zaGmwp 7 1 -2 0 2 1 9 1 ISSUE 2493 | antiquestradegazette.com | 22 May 2021 | UK £4.99 | USA $7.95 | Europe €5.50 S E E R 50 D V years A koopman I R N T antiques trade G T H E rare art KOOPMAN (see Client Templates for issue versions) [email protected] +44 (0)20 7242 7624 THE ART M ARKET WEEKLY www.koopman.art Big hitters return to major sales by Alex Capon The latest flagship sales of Modern and Contemporary art in New York showed a return to some normality after a difficult 14 months. The sighs of relief at the auction houses were almost palpable after the supply of major works had dropped off considerably during the pandemic but recovered signifi- cantly here, with some big-ticket items coming forward for last week’s series. Continued on page 4 Auction heads become dealers Pick Newton’s homage to Dorset Two long-standing auction department of the heads launch second careers as dealers this week month. tops Gloucestershire house sale David Houlston (oak furniture and works of art) and Paul Raison (Old Masters) Duke’s sale of property from Wormington Grange near paints manufacturer Winsor & Newton, enjoyed only a both recently left senior positions at Broadway in Gloucestershire held in Dorchester from modest career and went largely unrecognised during his Bonhams and Christie’s respectively. May 12-14 included a record for the Modern British lifetime. -

Arthur Graham Reynolds 1914–2013

GRAHAM REYNOLDS Arthur Graham Reynolds 1914–2013 GRAHAM REYNOLDS (the ‘Arthur’ was firmly suppressed from an early age) was born in Highgate on 10 January 1914. His father, Arthur T. Reynolds, a monu- mental mason, made the tombstones and crosses for Highgate cemetery, priding himself on his lettering. When Graham was about ten, his father died as the result of a war wound and his mother, Eva (née Mullins), daughter of a bank clerk, married Percy Hill, a property manager, who became mayor of Holborn in the 1930s. He was, according to Reynolds, a ‘bad tempered brute’, but he had the saving grace of having acquired a collection of mezzotints which provided the beginnings of a visual education in the home. Furthermore, the family’s move to 82 Gower Street, so near to the British Museum, encouraged Graham’s early interest in art. From Grove House Lodge, a local preparatory school, he obtained a schol- arship to Highgate School. The years there were largely unmemorable, except for the fact that one of the teachers was descended from Sir George Beaumont, Constable’s patron. At school, as he later recollected, he did not suffer unduly from being known as ‘the brain’ and ‘the swot’. In 1932, he went to Cambridge on a maths scholarship at Queens’ College. After the first year he switched to English, but something of the mathematician’s precision remained with him all his life. He used to say that if there had been a faculty of art history in Cambridge at the time, he would have joined that. -

1 Boston University Study Abroad London British Painting 1500–1900

Boston University Study Abroad London British Painting 1500–1900 CAS AH 388 (Elective A) Spring 2018 Instructor Information A. Name Dr Caroline Donnellan B. BU Telephone C. Email D. Office hours By appointment Course Overview This course is an introduction to British art covering the sixteenth to the nineteenth- century. As a category, British art is outside of the mainstream of Western European art surveys which usually concentrate on France, Italy, Spain and Holland. The course offers a unique opportunity for students to study British works of art. The British and foreign artists to be discussed will include Hans Holbein the Younger, Nicholas Hilliard, Daniel Mytens, Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, William Hogarth, Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, Joseph William Mallord Turner, John Constable, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones. The learning outcomes are that students will develop a robust knowledge and analytical understanding of British Painting 1500–1900 and will be able to critically think across a broad range of cultural and historical debates. The objective is that these tools will foster better synthetic skills which can be used throughout their academic development. Teaching Pattern Teaching Sessions will be divided between classroom lectures and field trips – where it is not possible to attend as a group these will be self-guided. Students should be dressed for all weather walking. Laptops are not permitted and mobile phones must be switched off. Listening to iPods or other devices is not permitted. Attendance at full class sessions, including visits is mandatory. Assessment Method Course Work Essay: Why and how does the image of Henry VIII change? Or Why and how does the image of Elizabeth I change? The essay counts for 50% of the overall mark and is due Monday 5 February at 8.45am, by 8.45am and is to be submitted to the Student Affairs Office. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOURTH STRFFT AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 . 737-4215/842-6353 Revised: July 1985 EXHIBITION FACT SHEET Title: THE TREASURE HOUSES OF BRITAIN: FIVE HUNDRED YEARS OF PRIVATE PATRONAGE AND ART COLLECTING Patrons; Their Royal Highnesses The Prince and Princess of Wales Dates: November 3, 1985 through March. 16, 1986. (This exhibition will not travel. Most loans from houses open to view are expected to remain in place until the late suitmer of 1985 and to be returned before many of the houses open for their visitors in the spring of 1986.) Credits: This exhibition is made possible by a generous grant from the Ford Motor Company. The exhibition was organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, in collaboration with the British Council and is supported by indemnities from Her Majesty's Treasury and the U.S. Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities. Further British assistance was supplied by the National Trust and the Historic Houses Association. British Airways has been designated the official carrier of the exhibition. History of the exhibition; The idea that the National Gallery of Art consider holding a major exhibition devoted to British art evolved in discussions with the British Council in 1979. J. Carter Brown, Director of the National Gallery of Art, proposed an exhibition on the British country house as a "vessel of civilization," bringing together works of art illustrating the extraordinary achievement of collecting and patronage throughout Britain over the past five hundred years. As this concept carried with it the additional, contemporary advantage of stimulating greater interest in and support of those houses open to public viewing, it was enthusiastically endorsed by the late Lord Howard of Henderskelfe, then-Chairman of the Historic Houses Association, Julian Andrews, Director of the Fine Arts Department of the British Council, and Lord Gibson, Chairman of the National Trust. -

A History of Kingship and the British Monarchy by Sir Roy Strong Harper Collins, London, 2005 ISBN 0-00-716054-2 £25

Coronation: A History of Kingship and the British Monarchy by Sir Roy Strong Harper Collins, London, 2005 ISBN 0-00-716054-2 £25 (Summer 2006) Church and King , the magazine of The Society of King Charles the Martyr 17-26 Sir Roy, one time director of the Victoria and Albert Museum, and of the National Portrait Gallery in London, is one of the foremost British arts critics, writers and broadcasters. He has now brought us what can, with some justification, be called the definitive history of the coronation. There have been many works on coronations – usually written in time for one – varying from the comprehensive 1937 history by the German scholar Percy Schramm, and the early twentieth century researches of father and son John and Leopold Wickham Legg, to more popular works. These latter have included books by Randolph Churchill (son of Sir Winston), Brian Barker and others who were personally involved (though in a relatively minor role) in a coronation. But although there has been a considerable amount of writing on some aspects of the coronation (usually highly technical) there has not, until now, been a major book which brings up to date the scholarship of the past century or so. Strong takes us through the history of the coronation (the subject is the coronation in Westminster Abbey, so Scottish coronations receive slight and only peripheral attention). This coverage is always with an eye to the contemporary context, but at the same time emphasising continuity. Indeed the coronation service shows remarkable resilience, with the form of the coronation of King Edgar in 973 (one of the earliest for which comprehensive details are available, and also one of the most important) being clearly recognisable as the forerunner of The Queen’s coronation in 1953. -

The William Shipley Group for Rsa History

THE WILLIAM SHIPLEY GROUP FOR RSA HISTORY Newsletter 41: 2014 FORTHCOMING MEETINGS 28 June 2014 at 2.30pm. Caleb Whitefoord – The Man Who Made Peace with America by Dr David Allan, FSA, Honorary President, WSG for RSA History. TwiCkenham Library, Garfield Road, TwiCkenham TW1 3JT. Admission £2 at door. Wine MerChant, Diplomat and Art Patron Caleb Whitefoord FRS. FSA (1734-1810) was eleCted a member of the SoCiety of Arts in 1762 on the proposal of his next-door neighbour and friend, Benjamin Franklin. He was aCtive in the SoCiety’s affairs serving first as a Committee member then as Chairman. In reCognition of his long serviCe in the Society’s affairs he was eleCted ViCe- President in 1800. This talk will Consider the role Whitefoord played in the peaCe negotiations between Great Britain and AmeriCa. 4 July 2014 from 9.30am to 1.00pm. Fellowship Centenary Symposium to Commemorate the centenary of the adoption of the style ‘Fellow’ by members of the RSA. Vikki Heywood, Chair of the RSA Trustees, will kindly welCome delegates and speakers, who inClude Professor John Mee and Dr Georgiana Green, University of York; Joanne Corden, ArChivist, Royal SoCiety; Dr Elizabeth Eger, King’s College London; Julian Pooley, FSA, The NiChols ArChive; Dr David Allan, FSA, FRSA, Honorary President WSG and Honorary Historian, RSA and Susan Bennett, WSG Honorary SeCretary. Full programme details will follow shortly. The Durham Street Auditorium at RSA, 8 John Adam Street, London WC2N 6EZ has been made available for this meeting thanks to Matthew Taylor, CEO, RSA. 5 July 2014 from 1.30 to 4.00pm. -

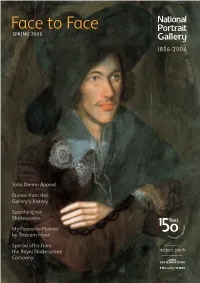

Face to Face SPRING 2006

Face to Face SPRING 2006 John Donne Appeal Stories from the Gallery’s history Searching for Shakespeare My Favourite Portrait by Tristram Hunt Special offer from the Royal Shakespeare Company From the Director ‘Often I have found a Portrait superior in real instruction to half-a-dozen written “Biographies”… or rather I have found that the Portrait was a small lighted candle by which Biographies could for the first t ime be read.’ RIGHT FROMLEFT Marjorie ‘Mo’ Mowlam by John Keane, 2001 Dame (Jean) Iris Murdoch by Tom Phillips, 1984–86 Sir Tim Berners-Lee by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, 2005 These portraits can be seen in Icons and Idols: Commissioning Contemporary Portraits from 2 March 2006 in the Porter Gallery So wrote Thomas Carlyle in 1854 in the years leading up to the founding of the National Exhibition supported by the Patrons of the National Portrail Gallery Portrait Gallery in 1856. Carlyle, with Lord Stanhope and Lord Macaulay, was one of the founding fathers of the Gallery, and his mix of admiration for the subject and interest in the character portrayed remains a strong thread through our work to this day. Much else has changed over the years since the first director, Sir George Scharf, took up his Very sadly John Hayes, Director of the National Portrait Gallery role, and as well as celebrating his achievements in a special display, we have created a from 1974 to 1994, died on timeline which outlines all the key events throughout the Gallery’s history. Our first Christmas Day aged seventy-six. -

Portraits of Queen Elizabeth I of England: Representations of Gender, Influence, and Power Nichole Lindquist-Kleissler [email protected]

University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas Summer Research Summer 2014 Portraits of Queen Elizabeth I of England: Representations of Gender, Influence, and Power Nichole Lindquist-Kleissler [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Lindquist-Kleissler, Nichole, "Portraits of Queen Elizabeth I of England: Representations of Gender, Influence, and Power" (2014). Summer Research. Paper 218. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research/218 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Summer Research by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lindquist-Kleissler 1 Introduction Queen Elizabeth I began her reign as the young, determined woman seen in her Coronation Robes at the age of twenty-five. [Figure 1] Progressively, she transformed into the deity Gloriana, immersed in layers of imperial promise and legend that is illustrated in the Ditchley Portrait rendered thirty three years later. [Figure 2] The remarkable development of Elizabeth’s person from human to divine, from woman to icon, was executed primarily through visual presentation. Portraiture was a powerful and unique tool for Elizabeth I of England who reigned from 1558 to1603. It allowed her not only to manipulate her image, but to embellish and perfect the way she wished to be perceived. Portraiture provided Elizabeth with the chance to communicate layers of significance, and meaning. 1 What was the portrayal of the Queen intended to accomplish? How did Elizabeth deal with gender norms and why? The precision and subtleties of an image were invaluable for a woman trying to prove her worth—particularly a woman in the extraordinary position that Elizabeth held: an unmarried monarch who ruled the British Isles. -

{Download PDF} V&A Pattern: Box-Set IV Kindle

V&A PATTERN: BOX-SET IV PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mary Schoeser,Anna Buruma,Samantha Erin Safer | 320 pages | 02 Apr 2012 | V & A Publishing | 9781851776832 | English | London, United Kingdom V&A Pattern: box-set IV To look through these images is to understand how we have collectively fantasized about the future of mobility for more than years. One common motif across all these images is that technology — primarily in the form of a car — will bring us a new way of getting around: one that is fast, frictionless and free, without a traffic jam in sight. From steampunk fantasies to afrofuturism, Hollywood blockbusters to concept-car extravaganzas, speed has figured at the heart of our mobile dreams. A view of the test track on top of the Fiat Lingotto factory in Turin. Raw materials were delivered to the ground floor with the assembly line going up through the building. The finished cars would then emerge at rooftop level and drive onto the track. This factory was built as a result of a collaboration between the Soviet Union and Ford to create an assembly plant to produce the Model A. New York is redrawn as a series of elevated walkways and train tracks with flying taxis and hovering past food drive-ins. Harley J. The Firebird 1 featured a gas turbo powered engine and a bubbletop single seat cockpit. Delegations of engineers and factory workers travelled to Stalingrad to help with the start of operations, training the Soviets in the processes of assembly-line production. Molino imagining the transport of the future in which commuters travel in selfcontained pods.