Abducens Palsy, 71 Abnormal Central Nervous System (CNS) Esotropia, 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Management of Microtropia

Br J Ophthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjo.58.3.281 on 1 March 1974. Downloaded from Brit. J. Ophthal. (I974) 58, 28 I Management of microtropia J. LANG Zirich, Switzerland Microtropia or microstrabismus may be briefly described as a manifest strabismus of less than 50 with harmonious anomalous correspondence. Three forms can be distinguished: primary constant, primary decompensating, and secondary. There are three situations in which the ophthalmologist may be confronted with micro- tropia: (i) Amblyopia without strabismus; (2) Hereditary and familial strabismus; (3) Residual strabismus after surgery. This may be called secondary microtropia, for everyone will admit that in most cases of convergent strabismus perfect parallelism and bifoveal fixation are not achieved even after expert treatment. Microtropia and similar conditions were not mentioned by such well-known early copyright. practitioners as Javal, Worth, Duane, and Bielschowsky. The views of Maddox (i898), that very small angles were extremely rare, and that the natural tendency to fusion was much too strong to allow small angles to exist, appear to be typical. The first to mention small residual angles was Pugh (I936), who wrote: "A patient with monocular squint who has been trained to have equal vision in each eye and full stereoscopic vision with good amplitude of fusion may in 3 months relapse into a slight deviation http://bjo.bmj.com/ in the weaker eye and the vision retrogresses". Similar observations of small residual angles have been made by Swan, Kirschberg, Jampolsky, Gittoes-Davis, Cashell, Lyle, Broadman, and Gortz. There has been much discussion in both the British Orthoptic Journal and the American Orthoptic journal on the cause of this condition and ways of avoiding it. -

Pediatric Ophthalmology/Strabismus 2017-2019

Academy MOC Essentials® Practicing Ophthalmologists Curriculum 2017–2019 Pediatric Ophthalmology/Strabismus *** Pediatric Ophthalmology/Strabismus 2 © AAO 2017-2019 Practicing Ophthalmologists Curriculum Disclaimer and Limitation of Liability As a service to its members and American Board of Ophthalmology (ABO) diplomates, the American Academy of Ophthalmology has developed the Practicing Ophthalmologists Curriculum (POC) as a tool for members to prepare for the Maintenance of Certification (MOC) -related examinations. The Academy provides this material for educational purposes only. The POC should not be deemed inclusive of all proper methods of care or exclusive of other methods of care reasonably directed at obtaining the best results. The physician must make the ultimate judgment about the propriety of the care of a particular patient in light of all the circumstances presented by that patient. The Academy specifically disclaims any and all liability for injury or other damages of any kind, from negligence or otherwise, for any and all claims that may arise out of the use of any information contained herein. References to certain drugs, instruments, and other products in the POC are made for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to constitute an endorsement of such. Such material may include information on applications that are not considered community standard, that reflect indications not included in approved FDA labeling, or that are approved for use only in restricted research settings. The FDA has stated that it is the responsibility of the physician to determine the FDA status of each drug or device he or she wishes to use, and to use them with appropriate patient consent in compliance with applicable law. -

Approved and Unapproved Abbreviations and Symbols For

Facility: Illinois College of Optometry and Illinois Eye Institute Policy: Approved And Unapproved Abbreviations and Symbols for Medical Records Manual: Information Management Effective: January 1999 Revised: March 2009 (M.Butz) Review Dates: March 2003 (V.Conrad) March 2008 (M.Butz) APPROVED AND UNAPPROVED ABBREVIATIONS AND SYMBOLS FOR MEDICAL RECORDS PURPOSE: To establish a database of acceptable ocular and medical abbreviations for patient medical records. To list the abbreviations that are NOT approved for use in patient medical records. POLICY: Following is the list of abbreviations that are NOT approved – never to be used – for use in patient medical records, all orders, and all medication-related documentation that is either hand-written (including free-text computer entry) or pre-printed: DO NOT USE POTENTIAL PROBLEM USE INSTEAD U (unit) Mistaken for “0” (zero), the Write “unit” number “4”, or “cc” IU (international unit) Mistaken for “IV” (intravenous) Write “international unit” or the number 10 (ten). Q.D., QD, q.d., qd (daily) Mistaken for each other Write “daily” Q.O.D., QOD, q.o.d., qod Period after the Q mistaken for Write (“every other day”) (every other day) “I” and the “O” mistaken for “I” Trailing zero (X.0 mg) ** Decimal point is missed. Write X mg Lack of leading zero (.X mg) Decimal point is missed. Write 0.X mg MS Can mean morphine sulfate or Write “morphine sulfate” or magnesium sulfate “magnesium sulfate” MSO4 and MgSO4 Confused for one another Write “morphine sulfate” or “magnesium sulfate” ** Exception: A trailing zero may be used only where required to demonstrate the level of precision of the value being reported, such as for laboratory results, imaging studies that report size of lesions, or catheter/tube sizes. -

Injections, Vaccines, and Other Physician-Administered Drugs Codes

INDIANA HEALTH COVERAGE PROGRAMS PROVIDER CODE TABLES Injections, Vaccines, and Other Physician-Administered Drugs Codes Note: Due to possible changes in Indiana Health Coverage Programs (IHCP) policy or national coding updates, inclusion of a code on the code tables does not necessarily indicate current coverage. See IHCP Banner Pages and Bulletins and the IHCP Fee Schedules for updates to coding, coverage, and benefit information. For information about using these code tables, see the Injections, Vaccines, and Other Physician-Administered Drugs provider reference module. Table 1 – Procedure Codes for Botulinum Toxin Injections Table 2 – Procedure Codes for Chemodenervation for Use with Botulinum Toxin Injections Table 3 – ICD-10 Diagnosis Codes for Medical Necessity of Botulinum Toxin Injections Table 1 – Procedure Codes for Botulinum Toxin Injections Reviewed/Updated: July 1, 2020 Procedure Code Code Description J0585 Injection, onabotulinumtoxin A, 1 unit J0586 Injection, abobotulinumtoxin A, 5 units J0587 Injection, rimabotulinumtoxin B, 100 units J0588 Injection, incobotulinumtoxin A, 1 unit Published: September 17, 2020 1 Indiana Health Coverage Programs Injections, Vaccines, and Other Physician-Administered Drugs Codes Table 2 – Procedure Codes for Chemodenervation for Use with Botulinum Toxin Injections Reviewed/Updated: July 1, 2020 Procedure Code Definition 42699 Unlisted procedure, salivary glands or ducts Esophagoscopy, flexible, transoral; with directed submucosal injection(s), 43201 any substance Esophagogastroduodenoscopy, -

Classification of Strabismus

Classification of strabismus Pr Dr Monique Cordonnier Université Libre de Bruxelles Most prominent feature to have in mind = BINOCULAR VISION potential ? Yes or No If the strabismus was present during the first 6- 8 months of life, there is no This potential means that potential for treatment (……) may restore normal binocular binocularity, warranting vision stability and avoiding recurrences Binocular vision = eyes are like wheels on the rails of a railtrack 1 What is BINOCULAR VISION ? 1. Normal - Bifoveolar fixation with normal visual acuity in each eye, no strabismus, no diplopia, normal retinal correspondence, normal fusional vergence amplitudes, normal stereopsis. 2. Subnormal (abnormal) – 1 or more of the following; anomalous retinal correspondence, suppression, deficient to no stereopsis, amblyopia, decreased fusional vergence amplitudes. 3. Absence of Binocular Vision - no simultaneous perception, no fusion, no stereopsis Besides, the classification of strabismus is based on a number of features including : . The relative position of the eyes . The time of onset (=clue for binocular vision potential), . Whether the deviation is intermittent (=clue for binocular vision potential) or constant . Whether the deviation is comitant (supranuclear cause) or incomitant (nuclear or infranuclear cause, clue for binocular vision potential if the eyes are straight in one position) . According to the associated refractive error (accommodative strabismus) 2 Most common types of strabismus in children Supranuclear causes Paralytic, muscular or -

International Council of Ophthalmology Residency Curriculum

International Council of Ophthalmology Residency Curriculum International Council of Ophthalmology 945 Green Street San Francisco, CA 94133 United States of America www.icoph.org © 2006, 2012 by The International Council of Ophthalmology All rights reserved. First edition 2006 Second edition 2012. International Council of Ophthalmology Residency Curriculum Introduction “Teaching the Teachers” The International Council of Ophthalmology (ICO) is committed to leading efforts to improve ophthalmic education to meet the growing need for eye care worldwide. To enhance educational programs and ensure best practices are available, the ICO focuses on "Teaching the Teachers," and offers curricula, conferences, courses, and resources to those involved in ophthalmic education. By providing ophthalmic educators with the tools to become better teachers, we will have better-trained ophthalmologists and professionals throughout the world, with the ultimate result being better patient care. Launched in 2012, the ICO’s Center for Ophthalmic Educators, educators.icoph.org, offers a broad array of educational tools, resources, and guidelines for teachers of residents, medical students, subspecialty fellows, practicing ophthalmologists, and allied eye care personnel. The Center enables resources to be sorted by intended audience and guides ophthalmology teachers in the construction of web-based courses, development and use of assessment tools, and applying evidence-based strategies for enhancing adult learning. The interactive feature, “Connections,” is the Center’s dynamic focal point, where ophthalmic educators can share ideas and collaborate with peers. The Center builds on the ICO’s original interactive online educational presence: World Ophthalmology Residency Development (WORD), which was developed in 2008 by Eduardo Mayorga, MD, ICO Director for E-Learning, and Gabriela Palis, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Center for Ophthalmic Educators. -

Z-Rpt Procedure Code Published Table

ForwardHealth Diagnosis Code-Restricted Physician-Administered Drug The following table contains information on diagnosis-restricted physician administered drugs. For each drug, the corresponding HCPCS procedure code and ICD-10 diagnosis code(s) and disease description(s) are listed. When one of the drugs is billed for a disease state listed for the drug, the drug does not require prior authorization (PA). When billing one of these drugs for a disease that is not listed below, PA is required. Peer-reviewed medical literature supporting the efficacy of the drug for the disease state must be submitted with the PA request. The information above only applies to billing of these services on a professional claim. Note: This table includes Wisconsin Medicaid’s most current information and may be updated periodically. HCPCS* Description Effective: 10/1/2017 J0205 INJECTION, ALGLUCERASE, PER 10 UNITS (CEREDASE) ICD-10 Description E7522 GAUCHER DISEASE J0585 INJECTION, ONABOTULINUMTOXINA, 1 UNIT (BOTOX)** Allowable diagnosis codes for members of any age. See next section for members 18 years and older with migraines. ICD-10 Description G114 HEREDITARY SPASTIC PARAPLEGIA G2402 DRUG INDUCED ACUTE DYSTONIA G2409 OTHER DRUG INDUCED DYSTONIA G241 GENETIC TORSION DYSTONIA G242 IDIOPATHIC NONFAMILIAL DYSTONIA G243 SPASMODIC TORTICOLLIS G245 BLEPHAROSPASM G248 OTHER DYSTONIA G2589 OTHER SPECIFIED EXTRAPYRAMIDAL AND MOVEMENT DISORDERS G35 MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS G512 MELKERSSON'S SYNDROME G513 CLONIC HEMIFACIAL SPASM G514 FACIAL MYOKYMIA G518 OTHER DISORDERS -

British Orthoptic Journal Volume 1, 1939

Transactions of the Orthoptic Association of Australia Volume 1, 1959 Charles Rasp. Presidential address 2 Peoples M, Charles Rasp The British Orthoptic Board 3 Willoughby L, Cashell GT Two examples of the A syndrome 8 Lance PM Monocular aphakia 10 Hawkeswood H A few words on convergence deficiency 13 Balfour B Hess charts, typical and atypical 14 Mann D Convergence strabismus with a small angle 19 Willoughby L, Cashell GT Monocular stimulation in the treatment of amblyopia ex anopsia 24 Carroll M Constant strabismus in adults 26 Kirkland M Binocular dynamics (clinical examinations) 28 Mann D An Orthoptic ABC 43 Willoughby L Radio astronomy 48 Kerdel RL Transactions of the Orthoptic Association of Australia Volume 2, 1960 Pan-Asian tour. Presidential address 1 Lance PM A study of patients at the Childrens Hospital 7 MacFarlane A Eccentric fixation and pleoptics 15 Lewis M Pleoptics in Melbourne 20 Carter M Occlusion clinic 21 MacFarlane A Case history. V syndrome 21 MacFarlane A Overconvergence in intermittent divergent squint 23 Hawkeswood H Two cases of convergence spasm 25 Mann D Bifocals in accommodative squint 28 Walker A An observation 30 Peoples M Esophoria to intermittent convergent squint 32 Hawkeswood H Some problems of ocular paresis 33 O’Connor B Atypical Duane’s syndrome 38 Kunst JM Superior oblique tucking; two cases 39 Mann D Transactions of the Orthoptic Association of Australia Volume 3, 1961 Supranuclear palsies (post-graduate lecture) 3 Lance PM Convergence (postgraduate lecture) 6 Lance PM Practical aspects of convergence 10 Hawkeswood H Surgical cases of intermittent divergent strabismus 15 Kirkland M A survey of patients at the hospital for sick children, Brisbane 21 Kirby J Some observations of pleoptics at Moorfields Eye Hospital 29 Mann D Notes of pleoptic treatment 31 Syme A Heterophoria 34 Mann D V syndrome (case history) 37 Macfarlane A Paresis of medial rectus with V sign 39 Balfour B. -

Two More Causes of Diplopia

12/2/2016 Other Causes Discussed Two More Causes of • Following cataract surgery Diplopia • Convergence abnormalities Creig S Hoyt MD MA • Divergence abnormalities San Francisco • Excluded- CN palsies, thyroid orbitopathy Following cataract surgery Convergence abnormalities • Reduced but not eliminated with topical anesthesia • Convergence insufficiency is common/benign • Myotoxicity most likely cause in cases with • Convergence paralysis implies neuro problem retrobulbar or peribulbar anesthesia • Beware of the older patient who progresses • Previous strabismus/amblyopia most likely from insufficiency to paralysis cause in cases with topical anesthesia 1 12/2/2016 Divergence abnormalities Case Number One • 36 year old complains of double vision with • Divergence insufficiency in young patients slight horizontal and vertical displacement implies neuro problem- subclinical 6th nerve that overlaps the other image. The second • Divergence insufficiency in older patients with image is described as “faint”. or without myopia is usually benign • What is the diagnosis? 2 12/2/2016 Differences in Pictures • Presence or absence of cyclotorsion! • Is the second image “faint”? • Do the images overlap? • How confusing is the double vision? 3 12/2/2016 Monocular Diplopia • Second image- “faint” or “ghost” • Overlap the rule; complete separation rare • Little or no cyclotorsion • Persists with occlusion of fellow eye • Disappears with pinhole 4 12/2/2016 Monocular Diplopia • Most common cause of diplopia in general eye practice — 25% of diplopia cases -

Eye Health 115 27

CURRICULUM, STATUTES & REGULATIONS FOR MS OPHTHALMOLOGY RAWALPINDI MEDICAL UNIVERSITY I PREFACE The horizons of Medical Education are widening & there has been a steady rise of global interest in Post Graduate Medical Education, an increased awareness of the necessity for experience in education skills for all healthcare professionals and the need for some formal recognition of postgraduate training in Ophthalmology. We are seeing a rise in the uptake of places on postgraduate courses in medical education, more frequent issues of medical education journals and the further development of e-journals and other new online resources. There is therefore a need to provide active support in Post Graduate Medical Education for a larger, national group of colleagues in all specialties and at all stages of their personal professional development. If we were to formulate a statement of intent to explain the purpose of this log book, we might simply say that our aim is to help clinical colleagues to teach and to help students to learn in a better and advanced way. This book is a state of the art log book with representation of all activities of the MS Ophthalmology program at RMU.A summary of the curriculum is incorporated in the logbook for convenience of supervisors and residents. MS curriculum is based on six Core Competencies of ACGME (Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education) including Patient Care, Medical Knowledge, System Based Practice, Practice Based Learning, Professionalism, Interpersonal and Communication Skills. A perfect monitoring system of a training program including monitoring of teaching and learning strategies, assessment and Research Activities cannot be denied so we at RMU have incorporated evaluation by Quality Assurance Cell and its comments in the logbook in addition to evaluation by University Training Monitoring Cell (URTMC). -

Suppression in Strabismus an Update

Br J Ophthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjo.68.3.174 on 1 March 1984. Downloaded from British Journal ofOphthalmology, 1984, 68, 174-178 Suppression in strabismus an update J. A. PRATT-JOHNSON AND G. TILLSON From the Department ofOphthalmology, University ofBritish Columbia, Vancouver, and the Department ofOphthalmology, Children's Hospital, Vancouver, BC, Canada SUMMARY Previous reports have described suppression scotomas, suppression varying with the type of strabismus and suppression confined to one halfofthe retina (hemiretinal suppression). Our findings show that suppression in all varieties of strabismus, with the exception of the monofixation syndrome, involves the whole of the visual field of the deviating eye except for its monocular temporal crescent. In the monofixation syndrome our findings show a small central suppression scotoma involving the fovea but leaving the rest ofthe visual field of the deviating eye unsuppressed. We could find no evidence to support the concept of hemiretinal suppression but found evidence to support the presence of a trigger mechanism for suppression which operates on a hemiretinal basis. The sensory adaptations of suppression, anomalous demonstrate the presence of a trigger mechanism for retinal correspondence (ARC), and amblyopia which suppression. As a result of our experiments we have occur in strabismus with onset during visual been able to look again at the literature on immaturity have been extensively studied by a variety suppression and realise the differences between our ofmethods. The investigation of all these adaptations findings and those of previous researchers result from has been limited by the difficulty of providing test the various testing methods used. A detailed situations which are close to the patient's normal description of the methods we used to explore and http://bjo.bmj.com/ seeing conditions and yet allow the function of each map the binocular field of vision in strabismic and eye, individually, to be assessed. -

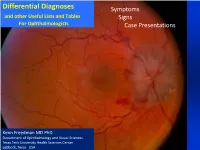

Differential Diagnoses Symptoms and Other Useful Lists and Tables Signs for Ophthalmologists Case Presentations

Differential Diagnoses Symptoms and other Useful Lists and Tables Signs For Ophthalmologists Case Presentations Kenn Freedman MD PhD Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center Lubbock, Texas USA Acknowledgments and Disclaimer The differential diagnoses and lists contained herein are not meant to be exhaustive, but are to give in most cases the most common causes of many ocular / visual symptoms, signs and situations. Included also in these lists are also some less common, but serious conditions that must be “ruled-out”. These lists have been based on years of experience, and I am grateful for God’s help in developing them. I also owe gratitude to several sources* including Roy’s classic text on Ocular Differential Diagnosis. * Please see references at end of document This presentation, of course, will continue to be a work in progress and any concerns or suggestions as to errors or omissions or picture copyrights will be considered. Please feel free to contact me at [email protected] Kenn Freedman Lubbock, Texas - October 2018 Disclaimer: The diagnostic algorithm for the diagnosis and management of Ocular or Neurological Conditions contained in this presentation is not intended to replace the independent medical or professional judgment of the physician or other health care providers in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine a patient’s care. Use of this Presentation The lists are divided into three main areas 1. Symptoms 2. Signs from the Eight Point Eye Exam 3. Common Situations and Case Presentations The index for all of the lists is given on the following 3 pages.