White House Transition Interview – Mclarty, Thomas, Chief of Staff

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

David Hume Kennerly Archive Creation Project

DAVID HUME KENNERLY ARCHIVE CREATION PROJECT 50 YEARS BEHIND THE SCENES OF HISTORY The David Hume Kennerly Archive is an extraordinary collection of images, objects and recollections created and collected by a great American photographer, journalist, artist and historian documenting 50 years of United States and world history. The goal of the DAVID HUME KENNERLY ARCHIVE CREATION PROJECT is to protect, organize and share its rare and historic objects – and to transform its half-century of images into a cutting-edge digital educational tool that is fully searchable and available to the public for research and artistic appreciation. 2 DAVID HUME KENNERLY Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist David Hume Kennerly has spent his career documenting the people and events that have defined the world. The last photographer hired by Life Magazine, he has also worked for Time, People, Newsweek, Paris Match, Der Spiegel, Politico, ABC, NBC, CNN and served as Chief White House Photographer for President Gerald R. Ford. Kennerly’s images convey a deep understanding of the forces shaping history and are a peerless repository of exclusive primary source records that will help educate future generations. His collection comprises a sweeping record of a half-century of history and culture – as if Margaret Bourke-White had continued her work through the present day. 3 HISTORICAL SIGNIFICANCE The David Hume Kennerly collection of photography, historic artifacts, letters and objects might be one of the largest and most historically significant private collections ever produced and collected by a single individual. Its 50-year span of images and objects tells the complete story of the baby boom generation. -

SHER-WOOD® Kemvar® Conversion Varnish Systems

SHER-WOOD® Kemvar® Conversion Varnish Systems COMPLETE, TOP-OF-THE-LINE SYSTEMS FOR WOOD FINISHING ✦ Tailored to fit your needs ✦ Good UV resistance ✦ High solids ✦ Fast drying ✦ Meets KCMA specifications ✦ HAPS Free ✦ UV absorber added ✦ Low VOC ✦ Low formaldehyde content PERFORMANCE AND COMPLIANCE Sher-Wood® Kemvar® Conversion Varnish Systems beautify and protect fine crafted wood products. They are designed to perform on wood products from office furniture to kitchen cabinets and many other interior wood applications. Sher-Wood Kemvar Conversion Varnish Systems feature advantages like lower VOC and HAPS levels, no reportable formaldehyde, excellent resistance to household chemicals, and excellent film build capability. Sher-Wood Kemvar Conversion Varnish Systems are fast drying formulations with high volume solids and they meet the strict test requirements of the Kitchen Cabinet Manufacturers Association (KCMA). TAKING TECHNOLOGY TO THE FINISH® SHER-WOOD® Kemvar® Conversion Varnish Systems Finishing Characteristics Production Efficiency The Sher-Wood® Kemvar® Conversion Varnish The Sher-Wood Kemvar Conversion Varnish Systems deliver durable, beautiful finishes that Systems are designed to keep your finishing line are perfectly suited to all kinds of manufactured up and running efficiently. All of the system’s wood products. In addition, they provide formulations are designed to dry fast and sand excellent toughness, moisture and mar resistance, easily. Sher-Wood Kemvar Conversion Varnish as well as great cold check resistance and good finishes can be applied with conventional, resistance to most household chemicals. airless, air-assisted airless and electrostatic spraying equipment. Performance Properties Sher-Wood Kemvar LF Water White Conversion Regulatory Compliance Varnish and Sher-Wood Kemvar Vinyl Sealer is our Sher-Wood Kemvar Conversion Varnish Systems top-of-the-line conversion varnish finishing system. -

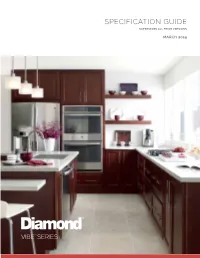

Specification Guide Supersedes All Prior Versions

SPECIFICATION GUIDE SUPERSEDES ALL PRIOR VERSIONS MARCH 2019 The basics made beautiful.™ From the dawning of the New Year comes a brand new Vibe Series. Take a look through our book – you’ll see we’ve analyzed the Diamond® Vibe™ Series inside, outside and upside down. From pricing and product to upgrades and upcharges we’ve trimmed the fat by stripping away old door styles and finishes and SKUs that just weren’t working as hard as they should be. Our new offering is leaner, cleaner, meaner and…. drumroll please…LESS EXPENSIVE!! The Diamond Vibe Series offers mainstream fashion and must-have features to suit your customer’s space with style. From all of us to all of you, warm wishes for a prosperous and fulfilling 2019. We can’t wait to see what you create! BRYANT Painted Coconut CONSTRUCTION ENHANCEMENTS We’ve improved structural integrity and enhanced upgrades all while lowering the overall average price to make your designs more competitive in the marketplace. A B C D A. Cabinet Box 1/2” Furniture board end panels; 3/8” Top and bottom B. Standard Drawer Solid wood with dovetail construction C. Standard Drawer Guides Full extension, under mount with Smart Stop™ and fast clip removal system D. Hinges Fully concealed, 6-way adjustable with Smart Stop™ PLYWOOD UPGRADE l l A. Cabinet Box Plywood Ends (PLE) u or All Plywood Construction (APW) u l Finished Ends (FB) modification available. u Unfinished ends standard. CONSTRUCTION ENHANCEMENTS KERNON Painted Icy Avalanche & Maritime MATCHING LAMINATE ENDS FOR MARITIME SPEC GUIDE PAGE 17 Automatic matching laminate ends for Maritime Painted and Maritime PureStyle™ products means fewer opportunities for error, a more streamlined ordering process, and reduced installation time in the field. -

Everything You Need to Know About Selecting Cabinets EVERYTHING YOU NEED to KNOW ABOUT SELECTING CABINETS

cabinets Everything You Need to Know About Selecting Cabinets EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT SELECTING CABINETS 2 EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT SELECTING CABINETS INTRODUCTION Cabinets set the tone for the look and feel of a kitchen. When it comes to cabinetry, there are countless options to help make your remodeling dreams a reality. While it’s great to have choic- es, it can be overwhelming without a basic understanding of the types of cabinets, doors and drawers that are available. 5 Types of Cabinets 8 Cabinet Construction 11 Cabinet Categories 12 Cabinet Doors 14 Cabinet Drawer Construction 16 Shelving Options 17 Finishes 20 Budgeting for a New Kitchen CONTACT US Cabinet-S-Top Phone : 330.239-3630 1977 Medina Road Fax : 330.239.4530 Medina, OH 44256 Email : [email protected] Web : www.cabinet-s-top.com 3 EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT SELECTING CABINETS 4 EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT SELECTING CABINETS Types of Cabinets There is almost an unlimited number of choices that can meet any style preference and budget need. Stock, custom and semi- custom refer to different production methods employed to manufacture cabinets. Stock Stock cabinets are ready-made, pre-manufactured and ship when ordered. They almost never can be altered or customized. What you see is what you get. There also is a broad range of quality differences among stock cabinets that may not be readily apparent. Pros: Short to no lead times to have your cabinets delivered. Stock cabinets can be ideal solutions for homeowners who want to increase the value of a home that they plan to sell in the near future. -

Policy and Politics by the Numbers;Аfor the President

5/12/2017 Policy and Politics by the Numbers; For the President, Polls Became a Defining Force in His Administration washingtonpost.com search nation, world… Policy and Politics by the Numbers; For the President, Polls Became a Defining Force in His Administration [FINAL Edition] The Washington Post Washington, D.C. Subjects: Series & special reports; Public opinion surveys; Policy making; Presidency Author: Harris, John F Date: Dec 31, 2000 Start Page: A.01 Section: A SECTION One night a week, a select group of White House aides and Cabinet members would file into the Yellow Oval Room in the White House residence. And Bill Clinton, the most polished and talkative politician of his era, for once would let someone else do the talking: a disheveled man who even friends say was ill at ease except when the conversation turned to numbers. The man was Clinton's pollster. The weekly residence meeting was the place where this president got his fix of the data that drove a presidency. As Clinton prepares to leave office 20 days from now, even his sharpest critics bow to his mastery of politics. This was a president who understood his times and became the dominant voice of them, who faced every conceivable adversity yet managed still to survive and prosper. What is less understood is that Clinton's political gifts were more than the magic of personality. They were a set of precise techniques that relied on constant gauging of public opinion, and constant responses to it in ways large and small. So Clinton's legacy is in many ways a story about polls. -

Granum, Deputy Press Secretary

Exit Interview with Rex Granum, Deputy Press Secretary Interviewer: Dr. Thomas Soapes of the Presidential Papers Staff December 10, 1980, in Rex Granum’s office in the White House Transcriber: Lyn Kirkland and Winnie Hoover Soapes: Let's start with a little bit of your background. Could you give me where you were born and your formal education? Granum: Born in Dayton, Ohio. My father was in Civil Service, so we did live in a number of Southern towns - Mobile, Alabama and Memphis, Tennessee. Grew up in Warner Robins, Georgia, from the third grade on went to public schools there. The University of Georgia --- journalism degree. I went--when I graduated from the University of Georgia, I went to the Atlanta Constitution, the morning paper in Atlanta, and eventually began to be a political writer there and came over and covered state government, covering Governor Jimmy Carter, his Press Secretary, Jody Powell, and his Executive Secretary, Hamilton Jordan, and then Frank Moore succeeded Hamilton when Hamilton went to--came to Washington during that change. So, that was the main point at which I became acquainted with the political beat. Soapes: How long were you on the political beat? Granum: Uh, I guess two years--two and a half years, something like that. Soapes: So the last--you say the last couple of years were--. Granum: --Yes. I covered the last six months of his time in the Governor's Office. And from March of '74--so it was longer than six months --I went over to the State Capitol in March of '74 and stayed there until early January of '76 and, of course, the President--or the Governor's term--Governor at that time, his term ended in January of '75. -

Hillary Clinton's Campaign Was Undone by a Clash of Personalities

64 Hillary Clinton’s campaign was undone by a clash of personalities more toxic than anyone imagined. E-mails and memos— published here for the first time—reveal the backstabbing and conflicting strategies that produced an epic meltdown. BY JOSHUA GREEN The Front-Runner’s Fall or all that has been written and said about Hillary Clin- e-mail feuds was handed over. (See for yourself: much of it is ton’s epic collapse in the Democratic primaries, one posted online at www.theatlantic.com/clinton.) Fissue still nags. Everybody knows what happened. But Two things struck me right away. The first was that, outward we still don’t have a clear picture of how it happened, or why. appearances notwithstanding, the campaign prepared a clear The after-battle assessments in the major newspapers and strategy and did considerable planning. It sweated the large newsweeklies generally agreed on the big picture: the cam- themes (Clinton’s late-in-the-game emergence as a blue-collar paign was not prepared for a lengthy fight; it had an insuf- champion had been the idea all along) and the small details ficient delegate operation; it squandered vast sums of money; (campaign staffers in Portland, Oregon, kept tabs on Monica and the candidate herself evinced a paralyzing schizophrenia— Lewinsky, who lived there, to avoid any surprise encounters). one day a shots-’n’-beers brawler, the next a Hallmark Channel The second was the thought: Wow, it was even worse than I’d mom. Through it all, her staff feuded and bickered, while her imagined! The anger and toxic obsessions overwhelmed even husband distracted. -

Foreign Policy/Domestic Politics Memo, HJ Memo, 6/77 Container: 34A

Collection: Office of the Chief of Staff Files Series: Hamilton Jordan's Confidential Files Folder: Foreign Policy/Domestic Politics Memo, HJ Memo, 6/77 Container: 34a Folder Citation: Office of the Chief of Staff Files, Hamilton Jordan's Confidential Files, Foreign Policy/Domestic Politics Memo, HJ Memo, 6/77, Container 34a Subject Terms: Foreign Policy Jimmy Carter Library 441 Freedom Parkway Atlanta GA 30307-1 ARCHIVAL NOTE~ The pages of this memo were originally unnumbered, then became out of order. The correct order and page numbers were then determined by comparison with an early photocopy of the document which retained the original correct order. The pencilled in numbers in brackets at the bottom of the pages represents the correct original order. During the time the pages were out of order, the page numbers were off by as much as 10 pages. The correct order was restored in September, 2008 ADN A Presidential Library Administered by the National Arcbtves and Records Administmtion ." ~#f" ! i~,". \ .. rI~,' Ill; ~f'f~ /? »7 1~l J~ i'· iit );'! ~j,:. ~£t~ <:O.?:FIDEWFIAL,LEYESONLY ~hi· ~t~' i f~ ~.:i- ~: i•.i.. H t. i· ~~: .TO: PRESIDENT CARTER ,~ t~ FROM: HAMILTON JORDAN~)( ·p"'·.··.··· f."r,.;.. L t·~ ~:;, F I have attempted in this memorandum to measure the ft -~ ~. domestic political implications of your foreign policy .~ t~•l~:.. I) and outline a comprehensive approach for winning public :kl~ ~~ and Congressional support for specific foreign policy ~t~.; :.¥ initiatives •... ~!~ ~ .I!-i ;~ 'r'n As this is highly sensitive subject matter, I typed ltit~. (.,~. this memorandum myself and the one other copy is in ;;i r~f.~ my office safe. -

White House Staffs: a Study

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work 5-1997 White House Staffs: A Study Eric Jackson Stansell University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Stansell, Eric Jackson, "White House Staffs: A Study" (1997). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/241 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM SENIOR PROJECT - APPROVAL Name: _Er~ __ ~t~~~g.Jl ____________________________________ _ College: J:..t"j.§_~ __~=i.~~~,=-~___ Department: _Cc:.ti~:a-t:;..-_~~_~~l~!:"~ __ - Faculty Mentor: __Q~!.. ___ M~~69&-1 ___ f~j"k%~.r~ld _________________ _ PROJECT TITLE: __~_\i.hik_H<?.~&_~t",-{:f~~ __ ~__ ~jM-/_: ________ _ I have reviewed this completed senior honors thesis with this student and certify that it is a project commensurate with honors level undergraduate research in this field. Signed: ~~#_~::t~~ Faculty Mentor ______________ , Date: ~/l7.t-~EL ______ --- Comments (Optional): "White House Staffs: A Study" by Eric Stansell August 11, 1997 "White House StatTs: A Study" by Eric Stansell Abstract In its current form, the modem presidency consists of much more than just a single individual elected to serve as the head of government. -

White House Compliance with Committee Subpoenas Hearings

WHITE HOUSE COMPLIANCE WITH COMMITTEE SUBPOENAS HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM AND OVERSIGHT HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 6 AND 7, 1997 Serial No. 105–61 Printed for the use of the Committee on Government Reform and Oversight ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 45–405 CC WASHINGTON : 1998 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Jan 31 2003 08:13 May 28, 2003 Jkt 085679 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 E:\HEARINGS\45405 45405 COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM AND OVERSIGHT DAN BURTON, Indiana, Chairman BENJAMIN A. GILMAN, New York HENRY A. WAXMAN, California J. DENNIS HASTERT, Illinois TOM LANTOS, California CONSTANCE A. MORELLA, Maryland ROBERT E. WISE, JR., West Virginia CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut MAJOR R. OWENS, New York STEVEN SCHIFF, New Mexico EDOLPHUS TOWNS, New York CHRISTOPHER COX, California PAUL E. KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida GARY A. CONDIT, California JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York STEPHEN HORN, California THOMAS M. BARRETT, Wisconsin JOHN L. MICA, Florida ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, Washington, THOMAS M. DAVIS, Virginia DC DAVID M. MCINTOSH, Indiana CHAKA FATTAH, Pennsylvania MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland JOE SCARBOROUGH, Florida DENNIS J. KUCINICH, Ohio JOHN B. SHADEGG, Arizona ROD R. BLAGOJEVICH, Illinois STEVEN C. LATOURETTE, Ohio DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois MARSHALL ‘‘MARK’’ SANFORD, South JOHN F. TIERNEY, Massachusetts Carolina JIM TURNER, Texas JOHN E. -

Transforming Marketing Forward Looking Information & Other Information

TRANSFORMING MARKETING FORWARD LOOKING INFORMATION & OTHER INFORMATION Cautionary Statement Regarding Forward-Looking Statements This communication may contain certain forward-looking statements (collectively, “forward-looking statements”) within the meaning of Section 27A of the U.S. Securities Act of 1933, as amended and Section 21E of the U.S. Exchange Act and the United States Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995, as amended, and “forward-looking information” under applicable Canadian securities laws. Statements in this document that are not historical facts, including statements about MDC’s or Stagwell’s beliefs and expectations and recent business and economic trends, constitute forward-looking statements. Words such as “estimate,” “project,” “target,” “predict,” “believe,” “expect,” “anticipate,” “potential,” “create,” “intend,” “could,” “should,” “would,” “may,” “foresee,” “plan,” “will,” “guidance,” “look,” “outlook,” “future,” “assume,” “forecast,” “focus,” “continue,” or the negative of such terms or other variations thereof and terms of similar substance used in connection with any discussion of current plans, estimates and projections are subject to change based on a number of factors, including those outlined in this section. Such forward-looking statements may include, but are not limited to, statements related to: future financial performance and the future prospects of the respective businesses and operations of MDC, Stagwell and the combined company; information concerning the proposed business combination -

Part C Webster L. Hubbell's Billing Practices and Tax Filings

PART C WEBSTER L. HUBBELL'S BILLING PRACTICES AND TAX FILINGS I. INTRODUCTION Shortly after their former partner Webster L. Hubbell became Associate Attorney General of the United States in January 1993, Rose Law Firm members in Little Rock found irregularities in Hubbell's billings for 1989-92. In March 1994, regulatory Independent Counsel Robert Fiske, received information that Hubbell may have violated federal criminal laws through his billing activities. Mr. Fiske then opened a criminal investigation. In the wake of these inquiries, Hubbell announced his resignation as the Associate Attorney General on March 14, 1994, saying this would allow him to settle the matter. Upon his appointment in August 1994, Independent Counsel Starr continued the investigation already started by Mr. Fiske. This resulted in Hubbell pleading guilty to one felony count of mail fraud and one felony count of tax evasion in December 1994, admitting that he defrauded his former partners and clients out of at least $394,000.1 On June 28, 1995, Judge George Howard sentenced Hubbell to twenty-one months' imprisonment.2 Sometime after Hubbell's sentencing, the Independent Counsel learned that a meeting had been held at the White House the day before Hubbell announced his resignation, where Hubbell's problems and resignation were discussed. Senior White House officials, including the President, 1 Plea Agreement, United States v. Webster Lee Hubbell, No. 94-241 (E.D. Ark. Dec. 6, 1994). Hubbell's attorney later agreed that Hubbell "obtained $482,410.83 by fraudulent means from the Rose Law Firm and its clients." Pre-sentence Investigation Report (Final Draft), United States v.