Introducing Android

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bootstomp: on the Security of Bootloaders in Mobile Devices

BootStomp: On the Security of Bootloaders in Mobile Devices Nilo Redini, Aravind Machiry, Dipanjan Das, Yanick Fratantonio, Antonio Bianchi, Eric Gustafson, Yan Shoshitaishvili, Christopher Kruegel, and Giovanni Vigna, UC Santa Barbara https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity17/technical-sessions/presentation/redini This paper is included in the Proceedings of the 26th USENIX Security Symposium August 16–18, 2017 • Vancouver, BC, Canada ISBN 978-1-931971-40-9 Open access to the Proceedings of the 26th USENIX Security Symposium is sponsored by USENIX BootStomp: On the Security of Bootloaders in Mobile Devices Nilo Redini, Aravind Machiry, Dipanjan Das, Yanick Fratantonio, Antonio Bianchi, Eric Gustafson, Yan Shoshitaishvili, Christopher Kruegel, and Giovanni Vigna fnredini, machiry, dipanjan, yanick, antoniob, edg, yans, chris, [email protected] University of California, Santa Barbara Abstract by proposing simple mitigation steps that can be im- plemented by manufacturers to safeguard the bootloader Modern mobile bootloaders play an important role in and OS from all of the discovered attacks, using already- both the function and the security of the device. They deployed hardware features. help ensure the Chain of Trust (CoT), where each stage of the boot process verifies the integrity and origin of 1 Introduction the following stage before executing it. This process, in theory, should be immune even to attackers gaining With the critical importance of the integrity of today’s full control over the operating system, and should pre- mobile and embedded devices, vendors have imple- vent persistent compromise of a device’s CoT. However, mented a string of inter-dependent mechanisms aimed at not only do these bootloaders necessarily need to take removing the possibility of persistent compromise from untrusted input from an attacker in control of the OS in the device. -

Top 20 Influencers

Top 20 AR/VR InfluencersWhat Fits You Best? Sanem Avcil Palmer Luckey @Sanemavcil @PalmerLuckey Founder of Coolo Games, Founder of Oculus Rift; CEO of Politehelp & And, the well known Imprezscion Yazilim Ve voice in VR. Elektronik. Chris Milk Alex Kipman @milk @akipman Maker of stuff, Key player in the launch of Co-Founder/CEO of Within. Microsoft Hololens. Creator of Focusing on innovative human the Microsoft Kinect experiences in VR. motion controller. Philip Rosedale Tony Parisi @philiprosedale @auradeluxe Founder of Head of AR and VR Strategy at 2000s MMO experience, Unity, began his VR career Second Life. co-founding VRML in 1994 with Mark Pesce. Kent Bye Clay Bavor @kentbye @claybavor Host of leading Vice President of Virtual Reality VR podcast, Voices of VR & at Google. Esoteric Voices. Rob Crasco Benjamin Lang @RoblemVR @benz145 VR Consultant at Co-founder & Executive Editor of VR/AR Consulting. Writes roadtovr.com, one of the leading monthly articles on VR for VR news sites in the world. Bright Metallic magazine. Vanessa Radd Chris Madsen @vanradd @deep_rifter Founder, XR Researcher; Director at Morph3D, President, VRAR Association. Ambassador at Edge of Discovery. VR/AR/Experiencial Technology. Helen Papagiannis Cathy Hackl @ARstories @CathyHackl PhD; Augmented Reality Founder, Latinos in VR/AR. Specialist. Author of Marketing Co-Chair at VR/AR Augmented Human. Assciation; VR/AR Speaker. Brad Waid Ambarish Mitra @Techbradwaid @rishmitra Global Speaker, Futurist, Founder & CEO at blippar, Educator, Entrepreneur. Young Global Leader at Wef, Investor in AugmentedReality, AI & Genomics. Tom Emrich Gaia Dempsey @tomemrich @fianxu VC at Super Ventures, Co-founder at DAQRI, Fonder, We Are Wearables; Augmented Reality Futurist. -

Present Challenges and Potential for Reform

THE FOREIGN INVESTMENT CLIMATE IN CHINA: PRESENT CHALLENGES AND POTENTIAL FOR REFORM HEARING BEFORE THE U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION WEDNESDAY, January 28, 2015 Printed for use of the United States-China Economic and Security Review Commission Available via the World Wide Web: www.uscc.gov UNITED STATES-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION WASHINGTON: 2015 ii U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION Hon. WILLIAM A. REINSCH, Chairman Hon. DENNIS C. SHEA, Vice Chairman Commissioners: CAROLYN BARTHOLOMEW DANIEL M. SLANE ROBIN CLEVELAND SEN. JAMES TALENT JEFFREY L. FIEDLER DR. KATHERINE C. TOBIN SEN. CARTE P. GOODWIN MICHAEL R. WESSEL MICHAEL R. DANIS, Executive Director The Commission was created on October 30, 2000 by the Floyd D. Spence National Defense Authorization Act for 2001 § 1238, Public Law No. 106-398, 114 STAT. 1654A-334 (2000) (codified at 22 U.S.C. § 7002 (2001), as amended by the Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act for 2002 § 645 (regarding employment status of staff) & § 648 (regarding changing annual report due date from March to June), Public Law No. 107-67, 115 STAT. 514 (Nov. 12, 2001); as amended by Division P of the “Consolidated Appropriations Resolution, 2003,” Pub L. No. 108-7 (Feb. 20, 2003) (regarding Commission name change, terms of Commissioners, and responsibilities of the Commission); as amended by Public Law No. 109- 108 (H.R. 2862) (Nov. 22, 2005) (regarding responsibilities of Commission and applicability of FACA); as amended by Division J of the “Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2008,” Public Law Nol. -

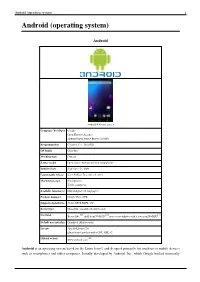

Android (Operating System) 1 Android (Operating System)

Android (operating system) 1 Android (operating system) Android Android 4.4 home screen Company / developer Google Open Handset Alliance Android Open Source Project (AOSP) Programmed in C (core), C++, Java (UI) OS family Unix-like Working state Current Source model Open source with proprietary components Initial release September 23, 2008 Latest stable release 4.4.2 KitKat / December 9, 2013 Marketing target Smartphones Tablet computers Available language(s) Multi-lingual (46 languages) Package manager Google Play, APK Supported platforms 32-bit ARM, MIPS, x86 Kernel type Monolithic (modified Linux kernel) [1] [2] [3] Userland Bionic libc, shell from NetBSD, native core utilities with a few from NetBSD Default user interface Graphical (Multi-touch) License Apache License 2.0 Linux kernel patches under GNU GPL v2 [4] Official website www.android.com Android is an operating system based on the Linux kernel, and designed primarily for touchscreen mobile devices such as smartphones and tablet computers. Initially developed by Android, Inc., which Google backed financially Android (operating system) 2 and later bought in 2005, Android was unveiled in 2007 along with the founding of the Open Handset Alliance: a consortium of hardware, software, and telecommunication companies devoted to advancing open standards for mobile devices. The first publicly available smartphone running Android, the HTC Dream, was released on October 22, 2008. The user interface of Android is based on direct manipulation, using touch inputs that loosely correspond to real-world actions, like swiping, tapping, pinching and reverse pinching to manipulate on-screen objects. Internal hardware such as accelerometers, gyroscopes and proximity sensors are used by some applications to respond to additional user actions, for example adjusting the screen from portrait to landscape depending on how the device is oriented. -

SDK Developer Reference Manual

SDK Developer Reference Manual Version 1.0 13 Aout 2019 Mobiyo Pôle Produit 94 Rue de Villiers 92832 Levallois Perret Cedex – France SAS au capital de 2 486 196€, RCS Paris 824 638 209, N° TVA Intracommunautaire : FR61 824 638 209, Code APE : 6201Z i TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of contents Overview ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1 What is the Mobiyo SDK . .1 What is an SDK ? �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������1 What is a REST Web Service? �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������1 Who may use this SDK? ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������2 Knowledge and skills . 2 How to read this documentation? . 2 Starting Guide �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 3 Basic Concept ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������3 Requests . 3 Responses ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 4 Character encoding ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 5 Dates . 5 Available formats ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

MINDSTORMS EV3 User Guide

User Guide TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction + Welcome ...................................................................................................................... 3 + How to Use This Guide .................................................................................... 4 + Help ................................................................................................................................. 5 EV3 Technology + Overview ..................................................................................................................... 6 + EV3 Brick ..................................................................................................................... 7 Overview ...................................................................................................................... 7 Installing Batteries ............................................................................................... 10 Turning On the EV3 Brick ................................................................................ 11 + EV3 Motors ................................................................................................................. 12 Large Motor ............................................................................................................... 12 Medium Motor ......................................................................................................... 12 + EV3 Sensors ............................................................................................................ -

A Comparative Analysis of Mobile Operating Systems Rina

International Journal of Computer Sciences and Engineering Open Access Research Paper Vol.-6, Issue-12, Dec 2018 E-ISSN: 2347-2693 A Comparative Analysis of mobile Operating Systems Rina Dept of IT, GGDSD College, Chandigarh ,India *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Available online at: www.ijcseonline.org Accepted: 09/Dec/2018, Published: 31/Dec/2018 Abstract: The paper is based on the review of several research studies carried out on different mobile operating systems. A mobile operating system (or mobile OS) is an operating system for phones, tablets, smart watches, or other mobile devices which acts as an interface between users and mobiles. The use of mobile devices in our life is ever increasing. Nowadays everyone is using mobile phones from a lay man to businessmen to fulfill their basic requirements of life. We cannot even imagine our life without mobile phones. Therefore, it becomes very difficult for the mobile industries to provide best features and easy to use interface to its customer. Due to rapid advancement of the technology, the mobile industry is also continuously growing. The paper attempts to give a comparative study of operating systems used in mobile phones on the basis of their features, user interface and many more factors. Keywords: Mobile Operating system, iOS, Android, Smartphone, Windows. I. INTRUDUCTION concludes research work with future use of mobile technology. Mobile operating system is the interface between user and mobile phones to communicate and it provides many more II. HISTORY features which is essential to run mobile devices. It manages all the resources to be used in an efficient way and provides The term smart phone was first described by the company a user friendly interface to the users. -

State of Mobile Linux Juha-Matti Liukkonen, Jan 5, 2011

State of Mobile Linux Juha-Matti Liukkonen, Jan 5, 2011 1 Contents • Why is this interesting in a Qt course? • Mobile devices vs. desktop/server systems • Android, Maemo, and MeeGo today • Designing software for mobile environments 2 Why is this interesting in a Qt course? 3 Rationale • Advances in technology make computers mobile • Low-power processors, displays, wireless network chipsets, … iSuppli, Dec 2008 • Laptops outsell desktop computers • High-end smartphones = mobile computers Nokia terminology • Need to know how to make software function well in a mobile device • Qt is big part of Symbian & Maemo/MeeGo API 4 Developing software for mobiles In desktop/server computing: • Android smartphones Java :== server C/C++ :== desktop • Eclipse, Java Qt was initially developed for desktop applications. • Symbian smartphones Mobile devices today are more powerful than the • NetBeans / Eclipse, Java ME desktops 10 years ago. • Qt Creator, C/C++ Of particular interest in this course. • Maemo / MeeGo smartphones • Qt Creator, C/C++ 5 The elephant in the room • In 2007, Apple change the mobile world with the iPhone • Touch user interface, excellent developer tools, seamless services integration, … • Modern operating system, shared with iPod and Mac product lines • Caught “industry regulars” with their pants down • Nokia, Google, Samsung, et al – what choice do they have? Linux! We don’t talk about the iPhone here. 6 iPad “killed the netbook” • In 2010, Apple introduced another mobile game changer • iPad = basically, a scaled-up iPhone with a -

Installation and Configuration Guide

IBM Cognos Software Development Kit Version 11.0.0 Installation and Configuration Guide IBM Note Before using this information and the product it supports, read the information in “Notices” on page 7. Product Information This document applies to IBM Cognos Software Development Kit Version 11.0.0 and may also apply to subsequent releases. Licensed Materials - Property of IBM © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 2005, 2016. US Government Users Restricted Rights – Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents Introduction.......................................................................................................... v Chapter 1. Installing and configuring the Software Development Kit....................... 1 Upgrading the Software Development Kit Software................................................................................... 1 Install the Software Development Kit on UNIX or Linux ............................................................................2 Install the Software Development Kit on Microsoft Windows ................................................................... 3 Configuring the Software Development Kit................................................................................................. 4 Uninstall the Software Development Kit from UNIX or Linux .................................................................... 5 Uninstall the Software Development Kit from Microsoft Windows .......................................................... -

City Research Online

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by City Research Online Giachetti, C. & Lanzolla, G. (2016). Product Technology Imitation Over the Product Diffusion Cycle: Which Companies and Product Innovations do Competitors Imitate More Quickly?. Long Range Planning, 49(2), pp. 250-264. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2015.05.001 City Research Online Original citation: Giachetti, C. & Lanzolla, G. (2016). Product Technology Imitation Over the Product Diffusion Cycle: Which Companies and Product Innovations do Competitors Imitate More Quickly?. Long Range Planning, 49(2), pp. 250-264. doi: 10.1016/j.lrp.2015.05.001 Permanent City Research Online URL: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/15192/ Copyright & reuse City University London has developed City Research Online so that its users may access the research outputs of City University London's staff. Copyright © and Moral Rights for this paper are retained by the individual author(s) and/ or other copyright holders. All material in City Research Online is checked for eligibility for copyright before being made available in the live archive. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to from other web pages. Versions of research The version in City Research Online may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check the Permanent City Research Online URL above for the status of the paper. Enquiries If you have any enquiries about any aspect of City Research Online, or if you wish to make contact with the author(s) of this paper, please email the team at [email protected]. -

Digitalpersona® Biometric SDK for Android®

EXTENDED ACCESS TECHNOLOGIES DigitalPersona® Biometric SDK for Android® The DIgitalPersona Biometric FINGERPRINT MATCHING ENGINE DigitalPersona Biometric SDKs Software Development Kit (SDK) The DigitalPersona FingerJet provide tools for developers for Android enables integrators matching engine, combined to create a new generation and developers to quickly add with DigitalPersona Fingerprint of commercial and internal fingerprint-based authentication Readers, offers accurate fingerprint applications delivering the to their Android applications. HID recognition, low false accept Global offers powerful SDKs which and false reject rates (FAR/FRR) convenience, security and feature accurate, high-performing coupled with fast execution time. biometric assurance of fingerprint authentication fingerprint authentication. STANDARDS SUPPORT algorithms. The DigitalPersona Biometric From time and attendance to EASY TO USE TOOLKITS SDK for Android fully embraces process control, point-of-sale In only a few hours, developers image, template, and compression and business applications, can easily integrate fingerprint standards. This provides developers DigitalPersona Biometric authentication into their Android with the flexibility to make SDKs allow developers to applications. Sample code is unfettered choices of matching quickly integrate fingerprint included to help programmers algorithms and the ability to authentication into their quickly understand how to capture comply with a growing customer software and hardware designs. a fingerprint, extract -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,068,604 B2 Leeds Et Al

USOO8068604B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,068,604 B2 Leeds et al. (45) Date of Patent: Nov. 29, 2011 (54) METHOD AND SYSTEM FOR EVENT 2004, OO67751 A1 4/2004 Vandermeijden et al. NOTIFICATIONS 2004/O120505 A1 6/2004 Kotzin et al. 2004/0235520 A1 11/2004 Cadiz et al. 2006,0003814 A1 1/2006 Moody et al. (75) Inventors: Richard Leeds, Bellevue, WA (US); 2006/0111085 A1 5, 2006 Lee Elon Gasper, Bellevue, WA (US) 2006/0148459 A1 7/2006 Wolfman et al. 2006/01995.75 A1 9, 2006 Moore et al. (73) Assignee: Computer Product Introductions 2006/0215827 A1 9/2006 Pleging et al. 2007, OO64921 A1 3/2007 Albukerk et al. Corporation, Bellevue, WA (US) 2007/0117554 A1 5/2007 Armos (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 2007/0264978 A1 1 1/2007 Stoops patent is extended or adjusted under 35 FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS U.S.C. 154(b) by 257 days. EP O 802 661 A2 10, 1997 EP 1098 SO3 A2 5, 2001 (21) Appl. No.: 12/339,429 EP 1814, 296 A1 8, 2007 * cited by examiner (22) Filed: Dec. 19, 2008 Primary Examiner — Md S. Elahee (65) Prior Publication Data (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm — LaRiviere, Grubman & US 2010/O161683 A1 Jun. 24, 2010 Payne, LLP (51) Int. Cl. (57) ABSTRACT H04M 3/00 (2006.01) (52) U.S. Cl. ................ 379/373.04; 379/76; 379/167.08; A method for generating a ring tone for a given caller based on 455/567 a prior conversation with that caller.