Chapter 4 DIVORCE and RESTITUTION UNDER HINDU

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why I Became a Hindu

Why I became a Hindu Parama Karuna Devi published by Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Copyright © 2018 Parama Karuna Devi All rights reserved Title ID: 8916295 ISBN-13: 978-1724611147 ISBN-10: 1724611143 published by: Jagannatha Vallabha Vedic Research Center Website: www.jagannathavallabha.com Anyone wishing to submit questions, observations, objections or further information, useful in improving the contents of this book, is welcome to contact the author: E-mail: [email protected] phone: +91 (India) 94373 00906 Please note: direct contact data such as email and phone numbers may change due to events of force majeure, so please keep an eye on the updated information on the website. Table of contents Preface 7 My work 9 My experience 12 Why Hinduism is better 18 Fundamental teachings of Hinduism 21 A definition of Hinduism 29 The problem of castes 31 The importance of Bhakti 34 The need for a Guru 39 Can someone become a Hindu? 43 Historical examples 45 Hinduism in the world 52 Conversions in modern times 56 Individuals who embraced Hindu beliefs 61 Hindu revival 68 Dayananda Saraswati and Arya Samaj 73 Shraddhananda Swami 75 Sarla Bedi 75 Pandurang Shastri Athavale 75 Chattampi Swamikal 76 Narayana Guru 77 Navajyothi Sree Karunakara Guru 78 Swami Bhoomananda Tirtha 79 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa 79 Sarada Devi 80 Golap Ma 81 Rama Tirtha Swami 81 Niranjanananda Swami 81 Vireshwarananda Swami 82 Rudrananda Swami 82 Swahananda Swami 82 Narayanananda Swami 83 Vivekananda Swami and Ramakrishna Math 83 Sister Nivedita -

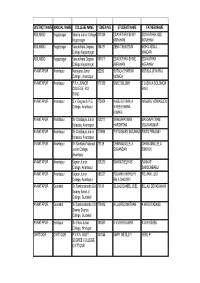

District Name Mandal Name College Name Token No

DISTRICT NAME MANDAL NAME COLLEGE NAME TOKEN NO. STUDENT NAME FATHER NAME ADILABAD Kagaznagar Manjira Junior Collage 133186 EDAVATHRA SHINY EDAVATHRA GEE Kagaznagar ABRAHAM ABRAHAM ADILABAD Kagaznagar Vasundhara Degree 194731 ZEBA TABASSUN MOHD ABDUL College Kagaznagar KHADAR ADILABAD Kagaznagar Vasundhara Degree 191011 EDAVATHRA SHINE EDAVATHRA College Kagaznagar ABRAHAM ABRAHAM ANANTAPUR Anantapur Narayana Junior 92299 KUTALA SHARON KUTALA JAYA RAJ College , Anantapur MONICA ANANTAPUR Anantapur P.R.K JUNIOR 171355 SAKE SALOMY S JASHUA SOLOMON COLLEGE, R.S RAJU ROAD ANANTAPUR Anantapur S.V. Degree & P.G. 173004 NAGURU VIMALA NAGURU VISWASUDU College, Anantapur NIREEKSHANA KUMARI ANANTAPUR Anantapur Sri Chaitanya Junior 203211 MANGAPATNAM MANGAPATNAM Kalasala, Anantapur HARSHITHA VIJAYAKUMAR ANANTAPUR Anantapur Sri Chaitanya Junior 170894 PINTO MARY MOUNIKA PINTO PRAKASH Kalasala, Anantapur ANANTAPUR Anantapur Sri Sai Baba National 72138 CHINNAMALLELA CHINNAMALLELA Junior College, SUGANDAM SIMIYUN Anantapur ANANTAPUR Anantapur Vignan Junior 128239 SANKATI ELIYAS SANKATI College, Anantapur SAMSONBABU ANANTAPUR Anantapur Vignan Junior 186227 POLANKI ANTHONY POLANKI JOJI College, Anantapur BALA SHOWRY ANANTAPUR Guntakal Sri Sankarananda Giri 73133 BILLALI DANIEL JOEL BILLALI DEVADANAM Swamy Aided Jr. College, Guntakal ANANTAPUR Guntakal Sri Sankarananda Giri 178682 A LOURDU NATHAN A AROGYADASS Swamy Degree College, Guntakal ANANTAPUR Hindupur Sri Vikas Junior 185353 K VIJAYA KUMAR K JAYA BABU College, Hindupur CHITTOOR CHITTOOR P.V.K.N. -

Ramanuja Darshanam

Table of Contents Ramanuja Darshanam Editor: Editorial 1 Sri Sridhar Srinivasan Who is the quintessential SriVaishnava Sri Kuresha - The embodiment of all 3 Associate Editor: RAMANUJA DARSHANAM Sri Vaishnava virtues Smt Harini Raghavan Kulashekhara Azhvar & 8 (Philosophy of Ramanuja) Perumal Thirumozhi Anubhavam Advisory Board: Great Saints and Teachers 18 Sri Mukundan Pattangi Sri Stavam of KooratazhvAn 24 Sri TA Varadhan Divine Places – Thirumal irum Solai 26 Sri TCA Venkatesan Gadya Trayam of Swami Ramanuja 30 Subscription: Moral story 34 Each Issue: $5 Website in focus 36 Annual: $20 Answers to Last Quiz 36 Calendar (Jan – Mar 04) 37 Email [email protected] About the Cover image The cover of this issue presents the image of Swami Ramanuja, as seen in the temple of Lord Srinivasa at Thirumala (Thirupathi). This image is very unique. Here, one can see Ramanuja with the gnyAna mudra (the sign of a teacher; see his right/left hands); usually, Swami Ramanuja’s images always present him in the anjali mudra (offering worship, both hands together in obeisance). Our elders say that Swami Ramanuja’s image at Thirumala shows the gnyAna mudra, because it is here that Swami Ramanuja gave his lectures on Vedarta Sangraha, his insightful, profound treatise on the meaning of the Upanishads. It is also said that Swami Ramanuja here is considered an Acharya to Lord Srinivasa Himself, and that is why the hundi is located right in front of swami Ramanuja at the temple (as a mark of respect to an Acharya). In Thirumala, other than Lord Srinivasa, Varaha, Narasimha and A VEDICS JOURNAL Varadaraja, the only other accepted shrine is that of Swami Ramanuja. -

Complete Volume

Sathya Sai Speaks Volume 36 (2003) INDEX 01. STRIVE FOR UNITY, PURITY, AND DIVINITY ...................................2 02. DEDICATE YOUR EVERYTHING TO GOD........................................12 03. EXPERIENCE OF UNITY IS REAL SATSANG....................................20 04. LET UNITY BE THE UNDERCURRENT EVERYWHERE ........................29 05. EXPERIENCE INNATE DIVINITY TO ATTAIN PEACE AND HAPPINESS.38 06. RISE ABOVE BODY CONSCIOUSNESS ..........................................47 07. RAMA NAVAMI DISCOURSE ........................................................57 08. CHANTING GOD'S NAME --THE ROYAL PATH TO LIBERATION .........65 09. PRACTISE AND PROPAGATE OUR SACRED CULTURE ......................73 10. LOVE AND RESPECT YOUR PARENTS AND SANCTIFY YOUR LIFE......81 11. SPIRIT OF SACRIFICE IS THE HALLMARK OF A TRUE DOCTOR .......91 12. CAST OFF BODY ATTACHMENT TO DEVELOP ATMIC CONSCIOUSNESS .....................................................................97 13. GOD’S BIRTHPLACE IS A PURE HEART ....................................... 107 14. GIVE UP DEHABHIMANA, DEVELOP ATMABHIMAN ....................... 114 15. DEVELOP THE SPIRIT OF BROTHERHOOD................................... 120 16. THE CULTURE OF BHARAT ........................................................ 125 17. THE ATMA TATTWA IS ONE IN ALL ............................................ 127 18. LOVE IS GOD – LIVE IN LOVE ................................................... 137 19. DIVINE DISCOURSE ................................................................ 145 20. -

(Sq.Mt) No of Kits Madan Kumar Karana

Name of the house owner Area available on No of S.No House number & Location Sri/Smt terrace (Sq.mt) kits Flat No:101,Plot No: 28, Sri Lakshmi Nilayam, Krishna 100 Sq.mt 1 Madan Kumar Karanam 1 kit Nagar colony, Near Gandhian School, Picket, Sec’bad 4th floor 2 K.Venkateshwar 4-7-12/46A,Macharam, Ravindranagar, Hyd 400 sft 1 kit No:102, Bhargav residency, Enadu colony, 3 N.V.Krishna Reddy 2500 sft 4th floor 1kit Kukatpally,Hyderabad 500 sft 4 Ghous Mohiuddin 5-6-180,Aghapura, Hyd 1 kit 2nd floor 5 Abdul Wahed 18-1-350/73,Yousuf bin colony,chandrayangutta,Hyd 1 kit 260, Road no: 9B,Alkapuri, 6 Cherukupalli Narasimha Rao 1200 sft 1 kit Near sai baba temple 10-5-112,Ahmed Nagar, Masab tank, 7 Ahmed Nizamuzzana Quraishi Rs.3000 sft 1 kit Hymayunangar,yderabad 9-7-121/1, Maruthi nagar, Opp:Santhosh Nagar 8 K.Vjai Kumar 100 sft 1 kit colony Saidabad, Hyd 9 B. Sugunakar 8-2-121, Behind Big Bazar, Punjagutta, Hyd 900 sft 1 kit 10 D. Narasimha Reddy 3.33.33 LV Reddi colony, Lingampally, Hyd 900 sft 1 kit 1-25-176/9/1, Rahul enclave, Shiva nagar, 11 D. Radhika 1000 sft 1 kit Kanajiguda, Trimalgherry, Secunderabad 2-3-800/5, Plot no: D-4,Road no:15,Co-op bank 12 B. Muralidhara Gupta 1600 sft 1 kit colony, Nagole, Hyderabad 13 Dr.Mazar Ali 12-2-334/B,Murad nagar, Mehdipatnam,Hyderabad 1600 sft 2 kits 14 Sukhavasi Tejorani 22-32/1, VV nagar, Dilshukhnagar, Hyd 800 sft 1 kit 15 Induri Bhaskara Reddy MIG 664, Phase I & II, KPHB colony,Kukatpally, Hyd 1000 sft 1 kit No-18, Subhodaya nagar colony, near HUDA park, 16 T.Sundary 150 yards 1 kit Opp: KPHB, Kukatpally, Hyd. -

Genesis and Growth of Saivism in Early Tamil Country

© 2020 JETIR June 2020, Volume 7, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) GENESIS AND GROWTH OF SAIVISM IN EARLY TAMIL COUNTRY N. PERUMAL Full time Ph.D., Research Scholar, Research Department of History, V.O. Chidambaram College, Thoothukudi – 8. (Affiliated to Manonmaniam Sundaranar University, Tirunelveli – 12.) ABSTRACT The aim of this article is to highlight the origin and growth of Saivism in early Tamil country. Hinduism consists of six systems namely Saivism. Vaishnavism, Ganapathiam , Kaumaram, souram and Saktham1. Saivism refers to the exclusive worship of Siva Saivam means that which has connection with Siva. Saivaites worship Siva as the supreme deity The Hinduism of Tamilagam has incorporate the Pre-Dravidian, Dravidian and Aryan religious beliefs and practices. This process of different racial practices in the sphere of religion had commenced by the Sangam age itself2. Key Words : Saivism, Lord Siva, Bhakti cult, SaivaNayanmars, Linga. Introduction: The Sangam literature contains numerous references to Siva and Thirumal worship3. Siva worship first started into fire worship, and then developed as sound subsequently as idol worship. In Tolkappiam4 in the Sutra beginning with Theivam, unevemamaram, the word Theivam indicates light. The Sangam poet Madurai Kannattanar, indicates that Sivan and Thirumal are the two great gods of ancient time5. Siva is referred as the God seated under the Banyentree6 which implies Siva, as Dakshinamurti seated under the Kallal tree. It has been said that Siva preached the message of the Vedas to the people of the world7. He is believed to have created the Panchabutas. Madurai Kanchi says that Lord with axe is the creator of water earth fire, air and the stars8. -

Fairs and Festivals (Separate Book for Each District)

PRG. 179.11 (1") 750 MAHBUBNAGAR CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME II ANDHRA PRADESH PART VII-B (12) ; - (12. Mahbubnagar District) A. CHANDRA SEKHAR OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE Superintendent of Census Operations, Andhra Pradesh Price: Rs. 6·75 P. or l_5 Sh. 9 d. or $1·43c. 1961 CENSUS PUBLICATIONS, ANDHRA PRADESH (All the Census, Publications of this State will bear Vol. No. II) PART I-A Gen eral Report PART I-B Report on Vital Statistics PART J-C Subsidiary Tables PART JI-A General Population Tables PART II-B (i) Economic Tables [B-1 to B-IV] PART II-B (ii) Economic Tables [B-V to B-IX] PART II-C Cultural and Migration Tables PART III Household Economic Tables PART IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments (with Subsidiary Tables) PART IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables PART V-A Special TabJes for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes ..PART V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes PART VI Yillage_Survcy- Monograph-s (46) PART VJI-A (I) I Handicrafts Sl,Jrvey Reports (Selected Crafts) PART VII-A (2) J PART VlI-B (1 to 20) ... Fairs and Festivals (Separate Book for each District) PART VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration I (No! for sale) PART VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation J PART IX State Atlas PART X Special Report on Hyderabad City District Census H~llldbooks - (Separate Volume for each District) o "» r» 3: "C " . _... _ - ·': ~ ~ ~' , FOREWORD Although since the beginning of history, foreign travellers and historians have recorded the principal marts and entrepots of commerce in India and have even mentioned important festivals and fairs and articles of special excellence available in them, no systematic regional inventory was attempted until the time of Dr. -

Hindu Festivels Under the Vijayanagar Rul – a Case of Vellore District a Brief Historical Study

© 2019 JETIR June 2019, Volume 6, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) HINDU FESTIVELS UNDER THE VIJAYANAGAR RUL – A CASE OF VELLORE DISTRICT A BRIEF HISTORICAL STUDY G. SURESH M.A.B.Ed., M. SIDDIQUE AHMED M.A., M.Phil. M. Phil (Part -Time) Research scholar Assistant Professor P.G & Research Department of History P.G &Research Department of History Islamiah College (Autonomous) Islamiah College (Autonomous) (Re-accredited by the NAAC with “A” Grade) (Re-accredited by the NAAC with “A” Grade) Vaniyambadi. Vaniyambadi. Religion is described as “the expression of man’s belief in and reverence for a superhuman power or powers regarded as creating and governing the universe”. So it can be said that a religion is “a particular system of belief in a god or gods and the activities that are connected with this system” phenomenologist have divided the great religions into two groups: prophetic and mystic. For example Hinduism and Buddhism are mystical; Christianity and Islam are prophetic. In the primitive stage there were many former of worship such as fetishism, tokenism, ancestor worship and the like. In all these forms besides acceptance of a supreme power, the code of ethics received much importance. There comes an enlightened mental and spiritual state which made man to love and worship God. Hinduism is certainly the oldest of all the religions that practical today. It is also the most varied of all the great religions of the world. Dr. Karan Singh Calls Hinduism “a geographical term based upon the Sanskrit name for the river Sindhu”. In fact Hinduism calls itself Santana Dharma, the eternal faith, because it is based not upon the teaching of single preceptor but on the collective widow and inspiration of great seers and sages from the very down of Indian Civilization. -

Sri Srinivasa Vaibhavam.Pub

Special Thanks To: Archakam SrI Ramakrishna DIkshitulu, Archaka Mirasidar, Srivari Temple, Thirumala Hills for his insightful and elaborate FOREWARD on the VaikhAnasa Agama and details of the practices at the garbha-gruham of the SrI sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org SrInivAsar thirukkoil at Tirumala. C O N T E N T S Introduction to VaikhAnasa Agama and worship i Mudal AzhwArs' anubhavam - Introduction 1 Mudal AzhwArs's Paasurams and Commentaries 3 Poigai azhwAr's paasurams on SrI SrInivAsar 5 BhUtattAzhwAr's paasurams on SrI SrInivAsar 41 PeyAzhwAr's paasurams on SrI SrInivAsar 80 nigamanam 135 sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org appendix Complete list of Sundarasimham-Ahobilavalli eBooks 137 sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org Malayappa Swamy in Sesha vAhanam SrI: INTRODUCTION TO VAIKHANASA AGAMA AND WORSHIP by Archakam SrI Ramakrsna Deekshitulu Archakam Mirasidar Srivari Temple, Tirumala Hills VAIKHANASA WORSHIP Om devarAja dayApAtram dIbhaktyAdi gunArnavam sadagopan.org sadagopan.org sadagopan.org bhrugvAdi munaya: putrA tasmai sri vikhanasE namaha|| nArAyanam sakamalam sakAlAmarEndram vaikhAnasam mam gurum nigamAgamEndram bhrugvathrikAsyapamarIchi mukhAn munIdrAn sarvAnaham kulagurum pranamAmi mUrdnA|| Amongst the Indian Communities of Priests, committed to the promotion of temple-culture, the Vaikhanasas occupy a significant position. The oldest such priestly communities, they even to this day largely function as temple priests. They find mention in Vedic corpus, the epics (Mahabharatha and Ramayana), the puranas -

High Court for the State of Telangana

COURT NO. 1 HONOURABLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE THE HONOURABLE SRI JUSTICE B.VIJAYSEN REDDY To be Heard on Thursday The 11th day of February 2021 - VIRTUAL MODE ( AT 10:30 AM ) (DAILY LIST) SNO CASE PETITIONER ADV. RESPONDENT ADV. DISTRICT FOR ADMISSION 1 WP(PIL)/14/2021 DR D V RAO ( SC FOR GAREEB GUIDE GP FOR GENERAL ADMINISTRATION HYDERABAD IA 1/2021 INTL ) (TG) NAMAVARAPU RAJESHWAR RAO(ASSGI) GP FOR EDUCATION (TG) 2 WP(PIL)/15/2021 Mamidala Thirumal Rao(PARTY IN GP FOR GENERAL ADMINISTRATION HYDERABAD IA 1/2021 PERSON) (TG) PASHAMKRISHNAREDDY(SC FOR GHMC 1 2 3 4) Y RAMA RAO GP FOR HOME (TG) NAMAVARAPU RAJESHWAR RAO(ASSGI) GP FOR MCPL ADMN URBAN DEV (TG) GP FOR ROADS BUILDINGS (TG) 3 WP(PIL)/16/2021 RAJASRI MANCHE GP FOR GENERAL ADMINISTRATION RANGA REDDY IA 1/2020 (TG) IA 2/2020 GP FOR MEDICAL HEALTH FW (TG) IA 3/2020 M/S INDUS LAW FIRM GP FOR HOME (TG) NAMAVARAPU RAJESHWAR RAO(ASSGI) 4 WP(PIL)/17/2021 NARESH REDDY CHINNOLLA GP FOR MCPL ADMN URBAN DEV (TG) HYDERABAD IA 1/2021 P SUDHEER RAO ADMISSION 5 WP/935/2017 V RAJAGOPAL REDDY GP FOR INDUSTRIES & COMMERCE (TG) RANGA REDDY IA 1/2017(WPMP CHALLA GUNARANJAN 1035/2017) P SHIV KUMAR (SC FOR TSPCB) IA 1/2018 6 WP/1366/2017 V V ANIL KUMAR GP FOR FORESTS (TG) KHAMMAM IA 1/2017(WPMP T V RAMANA RAO (SC FOR TSPCB) 1546/2017) R VINOD REDDY 7 WP/1506/2017 S SRINIVAS REDDY T V RAMANA RAO RANGA REDDY IA 1/2017(WPMP R VINOD REDDY 1715/2017) IA 4/2017(WPMP 7315/2017) 8 WP/1970/2017 T SUJAN KUMAR GP FOR FORESTS (TG) NIZAMABAD IA 1/2017(WPMP GP FOR PANCHAYAT RAJ RURAL DEV 2267/2017) (TG) GP FOR REVENUE -

Derrida and Contemporary Media Understanding P. Thirumal

4 Derrida and Contemporary Media Understanding P. Thirumal Department of Communication, The University of Hyderabad This intervention on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Jacques Derrida’s ‘Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences’ (1966) seeks to explore Derrida’s less widely circulated meditation on varied cultural, political, aesthetic and ethical practices relating to contemporary media technologies. Derrida’s thoughts on communication, I propose, straddle the hermeneutic of suspicion and also the hermeneutics of recovery. This article has five different parts to it and all of them seek to read Derrida not merely in relation to his philosophy of deconstruction but foreground his thoughts on media technology quite independently of his overarching explanatory framework. The first section deals with the near absence of Derrida in the discipline of Communication Studies, the second deals with Derrida as a media theorist, the third with Derrida as a fellow poststructuralist alongside Jean Baudrillard and Paul Virilio, the fourth with Derrida’s pronouncements on teletechnologies, and the last section with the conversation that Derrida had with the philosopher Bernard Stiegler on technology, including media technologies, at large. Communication Studies I hope to provide a particular genealogy of Communication Studies. In the US, it arose as an inter-war discipline and came to address the rapid deterioration of public space alongside technological advances in industrial production and circulation of cultural- economic goods. Prior to the war years, there was a split between Mass Communications Departments and Speech Departments in American Universities. In some sense, the split between Media Studies and Rhetorics was not of the philosophical kind. -

Excluding Patients Consultancy) Including Clinical Trials (Last Five Years

Revenue generated from consultancy projects (excluding Patients consultancy) including Clinical trials (Last five years) S. No. Name of the consultant Name of consultancy/clinical trial project Consulting/Sponsoring Year Revenue agency with contact details generated 1 Dr.J. DAMODHARAN A Randomized, open label, multicentre, comparative clinical trial Lambda Therapeutic 2014 232000 of IN-SUPR-002 in comparison with fixed dose combination (FDC) Research Ltd, Ahmedabad. of fenofibrate and rosuvastatin in patients with mixed Dyslipidemia. 2 Dr.ANITA RAMESH Open label randomized bioequivalence study to evaluate the Cliantha Research Ltd. 2014 1900000 pharmacokinetic (PK) and safety profile of Bevacizumab Biosimilar (BEVZ92) in combination with FOLFOX or FOLFIRI versus Bevacizumab (AVASTIN®) in combination with FOLFOX or FOLFIRI as first-line treatment in patients with metastatic ColoRectal Cancer (mCRC) 3 Dr.S.ANANDAN A Prospective, Open-Label, Multicenter, Randomized, Active- Max Neeman Medical 2014 1430400 Controlled Study to Compare the Efficacy of Alpecin Liquid Anti International Limited. Hair Loss Treatment to Minoxidil 5% Solution in the Management of Androgenetic Alopecia 4 Dr.SHANTHI A multicentric study, to assess the immunogenicity and the PROSPER CHANNEL 2014 300000 VIJAYARAGHAVAN safety of ‘Inactivated Hepatitis A Vaccine (Healive®)’ Lifescience India Pvt. Ltd. administered to healthy adults. 5 Dr. M.Manickavasagam Protocol No.: PEGF/USV/P3/001 A Phase III, Randomized, GVK Biosciences Pvt. Ltd. 2014 70000 Multicentric, Open-label, Equivalence Design Study to Compare the Safety and Efficacy of USV Pegfilgrastim and Neulasta® in Patients Receiving Doxorubicin and Docetaxel as a Combination Chemotherapy for Breast Cancer 6 Dr.A.J.HEMAMALINI Effect of Omega 3 fatty acid (Fish Oil / Algal Oil) enriched Tamilnadu Dairy 2014 75000 functional dairy foods on the lipid profile of borderline high Development hyperlipidemic adults.