Volume 14, Number 2: Spring 2017 Volume 14, Number 2 • Spring 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Overview of Hakka Migration History: Where Are You From?

客家 My China Roots & CBA Jamaica An overview of Hakka Migration History: Where are you from? July, 2016 www.mychinaroots.com & www.cbajamaica.com 15 © My China Roots An Overview of Hakka Migration History: Where Are You From? Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................................................................................... 3 Five Key Hakka Migration Waves............................................................................................. 3 Mapping the Waves ....................................................................................................................... 3 First Wave: 4th Century, “the Five Barbarians,” Jin Dynasty......................................................... 4 Second Wave: 10th Century, Fall of the Tang Dynasty ................................................................. 6 Third Wave: Late 12th & 13th Century, Fall Northern & Southern Song Dynasties ....................... 7 Fourth Wave: 2nd Half 17th Century, Ming-Qing Cataclysm .......................................................... 8 Fifth Wave: 19th – Early 20th Century ............................................................................................. 9 Case Study: Hakka Migration to Jamaica ............................................................................ 11 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 11 Context for Early Migration: The Coolie Trade........................................................................... -

Official Report of Proceedings

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL — 5 February 1986 565 OFFICIAL REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 5 February 1986 The Council met at half-past Two o'clock PRESENT HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR (PRESIDENT) SIR EDWARD YOUDE, G.C.M.G., M.B.E. THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF SECRETARY SIR DAVID AKERS-JONES, K.B.E., C.M.G., J.P. THE HONOURABLE THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY SIR JOHN HENRY BREMRIDGE, K.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE THE ATTORNEY GENERAL MR. MICHAEL DAVID THOMAS, C.M.G., Q.C. THE HONOURABLE LYDIA DUNN, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHEN SHOU-LUM, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PETER C. WONG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ERIC PETER HO, C.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR TRADE AND INDUSTRY DR. THE HONOURABLE HO KAM-FAI, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALLEN LEE PENG-FEI, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE HU FA-KUANG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-CHUEN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JOHN JOSEPH SWAINE, O.B.E., Q.C., J.P. THE HONOURABLE STEPHEN CHEONG KAM-CHUEN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG YAN-LUNG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS. SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARIA TAM WAI-CHU, O.B.E., J.P. DR. THE HONOURABLE HENRIETTA IP MAN-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN NAI-KEONG, C.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR LANDS AND WORKS THE HONOURABLE CHAN YING-LUN, J.P. -

Polite in Public Meet the Two Irregular Joes Behind the Cameras

Polite in Public Meet the two irregular Joes behind the cameras Cosima New War: von Bonin End of democracy, An artist whose start of a monarchy creations are “Roger and Out” Melrose Avenue Where to shop and what to eat 2 BUZZ 10.04.07 daily.titan daily.titan BUZZ 10.04.07 3 URBAN OUT-LOOKERS POLITE IN Two guys, some cameras PUBLIC and a badass photobooth ROGER & OUT “CHUCK’S” ZACHARY LEVI The Buzz Editor: The Daily Titan 714.278.3373 Jennifer Caddick The Buzz Editorial 714.278.5426 [email protected] LOCKED & LOADED Executive Editor: Editorial Fax 714.278.4473 Ian Hamilton The Buzz Advertising FOR MISFIRE 714.278.3373 [email protected] Director of Advertising Fax 714.278.2702 Advertising: The Buzz , a student publication, is a supplemental Stephanie Birditt insert for the Cal State Fullerton Daily Titan. It is printed every Thursday. The Daily Titan operates independently Assistant Director of of Associated Students, College of Communications, Advertising: CSUF administration and the CSU system. The Daily Titan Sarah Oak has functioned as a public forum since inception. Unless implied by the advertising party or otherwise stated, advertising in the Daily Titan is inserted by commercial Production: activities or ventures identified in the advertisements Jennifer Caddick themselves and not by the university. Such printing is not to be construed as written or implied sponsorship, Account Executives: endorsement or investigation of such commercial Nancy Sanchez enterprises. Juliet Roberts Copyright ©2006 Daily Titan /FX4VNNFS%SJOL1SJDFTr̾BOEPWFS 2 BUZZ 10.04.07 daily.titan daily.titan BUZZ 10.04.07 3 Melrose, you should keep in mind MELROSE that most store managers allow you to bargain. -

Re-Examining the Philosophical Underpinnings of the Melting Pot Vs. Multiculturalism in the Current Immigration Debate in the United States

Re-examining the Philosophical Underpinnings of the Melting Pot vs. Multiculturalism in the Current Immigration Debate in the United States Daniel Woldeab College of Individualized Studies, Metropolitan State University, St. Paul, MN, USA [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8267-7570 Robert M. Yawson School of Business, Quinnipiac University Hamden, CT, USA [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6215-4345 Irina M. Woldeab Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, St. Paul, MN, USA [email protected] In: Harnessing Analytics for Enhancing Healthcare & Business. Proceedings of the 50th Northeast Decision Sciences Institute (NEDSI) Annual Meeting, Pgs. 264 - 285. Virtual Conference, March 26-27, 2021. https://doi.org/10.31124/advance.14749101.v1 Copyright ©2021 Daniel Woldeab, Robert M. Yawson, and Irina Woldeab 2 Abstract Immigration to the United States is certainly not a new phenomenon, and it is therefore natural for immigration, culture and identity to be given due attention by the public and policy makers. However, current discussion of immigration, legal and illegal, and the philosophical underpinnings is ‘lost in translation’, not necessarily on ideological lines, but on political orientation. In this paper we reexamine the philosophical underpinnings of the melting pot versus multiculturalism as antecedents and precedents of current immigration debate and how the core issues are lost in translation. We take a brief look at immigrants and the economy to situate the current immigration debate. We then discuss the two philosophical approaches to immigration and how the understanding of the philosophical foundations can help streamline the current immigration debate. Keywords: Immigration, multiculturalism, melting pot, ethnic identity, acculturation, assimilation In: Harnessing Analytics for Enhancing Healthcare & Business. -

Our Printing Services out of This World

B4 Friday, Feb. 3, 2012 | TV | www.kentuckynewera.com FRIDAY PRIMETIME FEBRUARY 3, 2012 N - NEW WAVE M - MEDIACOM S1 - DISH NETWORK S2 - DIRECTV N M 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 1 AM 1:30 S1 S2 :35 :05 :35 :35 (2) (2) WKRN [2] Nashville's Nashville's Nashville's ABC World Nashville's Wheel of Shark Tank (SP) (N) Primetime: What 20/20 News 2 at News Jimmy Kimmel Live Extra Law & Order: C.I. Paid ABC News 2 News 2 News 2 News News 2 Fortune Would You Do? (N) 10 p.m. "The Unblinking Eye" Program 2 2 :35 :35 :35 :05 (4) WSMV [4] Channel 4 Channel 4 Channel 4 NBC News Channel 4 News at 6 Think You Are "Martin Grimm "Organ Dateline NBC Channel 4 Jay Leno Debra Late Night With Carson Today Show NBC News News News 5 p.m. Sheen" (SP) (N) Grinder" (N) News Messing, Jean Dujardin Jimmy Fallon Daly 4 4 :35 :35 :35 :05 (5) (5) WTVF [5] News 5 Inside News 5 CBSNews News Channel 5 A Gifted Man "In Case CSI: NY "Brooklyn 'Til I Blue Bloods "The Job" News 5 David Letterman LateL Rachel Bilson, Frasier N.Berkus Katherine CBS Edition of Blind Spots" (N) Die" (N) (N) David Milch (N) Heigl, Sunny Anderson 5 5 :35 :35 :35 :05 (6) (6) WPSD Dr. -

9 Tokyo Standardization, Ludic Language Use and Nascent Superdiversity

9 Tokyo Standardization, ludic language use and nascent superdiversity Patrick Heinrich and Rika Yamashita The study of language in the city has never been a prominent subject in Japanese sociolinguistics. The negligence of city sociolinguistics in Japan notwithstanding, there is a wide range of issues to be found in Tokyo, which reveal the intricate ways in which language and society relate to one another.1 In this chapter, we discuss two interrelated issues. Firstly, we outline the case of language standardization, which subsequently led to various destandardization phenomena and ludic language use. Secondly, we discuss how language diversity in Tokyo has grown in recent years and how it is no longer swept under the carpet and hidden. Tokyoites, too, are diversify- ing as an effect. We shall start, though, with a brief sociolinguistic history of Tokyo. From feudal Edo to Tokyo as a global city There exists no such place as “Tokyo City”. There is “Inner Tokyo”, comprised of 23 wards; there is “Metropolitan Tokyo” made up of the 23 wards and the Tama region; and there is “Greater Tokyo”, which refers to Metropolitan Tokyo plus the surrounding prefectures of Chiba, Kanagawa and Saitama. The Tama region, rural until 1920, is now home to one third of the population of Tokyo Metropolis, while Kanagawa, Chiba and Saitama prefecture have doubled their population over the past 50 years. Greater Tokyo comprises more than 35 million inhabitants. It is the largest urban center on earth. One third of the Japanese population lives there on less than 4% of the Japanese territory – and the number of inhabitants continues to grow. -

Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture David Endresak [email protected]

Eastern Michigan University DigitalCommons@EMU Senior Honors Theses Honors College 2006 Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture David Endresak [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.emich.edu/honors Recommended Citation Endresak, David, "Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture" (2006). Senior Honors Theses. 322. http://commons.emich.edu/honors/322 This Open Access Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at DigitalCommons@EMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@EMU. For more information, please contact lib- [email protected]. Girl Power: Feminine Motifs in Japanese Popular Culture Degree Type Open Access Senior Honors Thesis Department Women's and Gender Studies First Advisor Dr. Gary Evans Second Advisor Dr. Kate Mehuron Third Advisor Dr. Linda Schott This open access senior honors thesis is available at DigitalCommons@EMU: http://commons.emich.edu/honors/322 GIRL POWER: FEMININE MOTIFS IN JAPANESE POPULAR CULTURE By David Endresak A Senior Thesis Submitted to the Eastern Michigan University Honors Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors in Women's and Gender Studies Approved at Ypsilanti, Michigan, on this date _______________________ Dr. Gary Evans___________________________ Supervising Instructor (Print Name and have signed) Dr. Kate Mehuron_________________________ Honors Advisor (Print Name and have signed) Dr. Linda Schott__________________________ Dennis Beagan__________________________ Department Head (Print Name and have signed) Department Head (Print Name and have signed) Dr. Heather L. S. Holmes___________________ Honors Director (Print Name and have signed) 1 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Printed Media.................................................................................................. -

Identity Under Japanese Occupation

1 “BECOMING JAPANESE:” IDENTITY UNDER JAPANESE OCCUPATION GRADES: 9-12 AUTHOR: Katherine Murphy TOPIC/THEME: Japanese Occupation, World War II, Korean Culture, Identity TIME REQUIRED: Two 60-minute periods BACKGROUND: The lesson is based on the impact of the Japanese occupation of Korea during World War II on Korean culture and identity. In particular, the lesson focuses on the Japanese campaign in 1940 to encourage Koreans to abandon their Korean names and adopt Japanese names. This campaign was known as “sōshi-kaimei." The purpose of this campaign, along with campaigns requiring Koreans to recite an oath to the Japanese Emperor and bow at Shinto shrines, were to make the Korean people “Japanese” and hopefully, loyal subjects of the Japanese Empire by abandoning their Korean identity and loyalties. These cultural policies and campaigns were key to the Japanese war effort during World War II. The lesson draws from the students’ lives as well as two books: Lost Names: Scenes from a Korean Boyhood by Richard E. Kim and Under the Black Umbrella: Voices from Colonial Korea 1910-1945 by Hildi Kang. CURRICULUM CONNECTION: The lesson is intended to use the major themes from the summer reading book Lost Names: Scenes from a Korean Boyhood to introduce students to one of the five essential questions of the World History II course: How is identity constructed? How does identity impact human experience? In first investigating the origin of their own names and the meaning of Korean names, students can begin to explore the question “How is identity constructed?’ In examining how and why the Japanese sought to change the Korean people’s names, religion, etc during World War II, students will understand how global events such as World War II can impact an individual. -

The Paradigm of Hakka Women in History

DOI: 10.4312/as.2021.9.1.31-64 31 The Paradigm of Hakka Women in History Sabrina ARDIZZONI* Abstract Hakka studies rely strongly on history and historiography. However, despite the fact that in rural Hakka communities women play a central role, in the main historical sources women are almost absent. They do not appear in genealogy books, if not for their being mothers or wives, although they do appear in some legends, as founders of villages or heroines who distinguished themselves in defending the villages in the absence of men. They appear in modern Hakka historiography—Hakka historiography is a very recent discipline, beginning at the end of the 19th century—for their moral value, not only for adhering to Confucian traditional values, but also for their endorsement of specifically Hakka cultural values. In this paper we will analyse the cultural paradigm that allows women to become part of Hakka history. We will show how ethical values are reflected in Hakka historiography through the reading of the earliest Hakka historians as they depict- ed Hakka women. Grounded on these sources, we will see how the narration of women in Hakka history has developed until the present day. In doing so, it is necessary to deal with some relevant historical features in the construc- tion of Hakka group awareness, namely migration, education, and women narratives, as a pivotal foundation of Hakka collective social and individual consciousness. Keywords: Hakka studies, Hakka woman, women practices, West Fujian Paradigma žensk Hakka v zgodovini Izvleček Študije skupnosti Hakka se močno opirajo na zgodovino in zgodovinopisje. -

The Winston Churchill Memorial Trust of Australia

THE WINSTON CHURCHILL MEMORIAL TRUST OF AUSTRALIA 2015 Churchill Fellowship Report by Ms Bronnie Mackintosh PROJECT: This Churchill Fellowship was to research the recruitment strategies used by overseas fire agencies to increase their numbers of female and ethnically diverse firefighters. The study focuses on the three most widely adopted recruitment strategies: quotas, targeted recruitment and social change programs. DISCLAIMER I understand that the Churchill Trust may publish this report, either in hard copy or on the internet, or both, and consent to such publication. I indemnify the Churchill Trust against loss, costs or damages it may suffer arising out of any claim or proceedings made against the Trust in respect for arising out of the publication of any report submitted to the Trust and which the Trust places on a website for access over the internet. I also warrant that my Final Report is original and does not infringe on copyright of any person, or contain anything which is, or the incorporation of which into the Final Report is, actionable for defamation, a breach of any privacy law or obligation, breach of confidence, contempt of court, passing-off or contravention of any other private right or of any law. Date: 16th April 2017 1 | P a g e Winston Churchill Fellowship Report 2015. Bronnie Mackintosh. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 PROGRAMME 6 JAPAN 9 HONG KONG 17 INDIA 21 UNITED KINGDOM 30 STAFFORDSHIRE 40 CAMBRIDGE 43 FRANCE 44 SWEDEN 46 CANADA 47 LONDON, ONTARIO 47 MONTREAL, QUEBEC 50 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 52 NEW YORK CITY 52 GIRLS FIRE CAMPS 62 LOS ANGELES 66 SAN FRANCISCO 69 ATLANTA 71 CONCLUSIONS 72 RECOMMENDATIONS 73 IMPLEMENTATION AND DISSEMINATION 74 2 | P a g e Winston Churchill Fellowship Report 2015. -

Drug Trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle

Drug trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy To cite this version: Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy. Drug trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle. An Atlas of Trafficking in Southeast Asia. The Illegal Trade in Arms, Drugs, People, Counterfeit Goods and Natural Resources in Mainland, IB Tauris, p. 1-32, 2013. hal-01050968 HAL Id: hal-01050968 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01050968 Submitted on 25 Jul 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Atlas of Trafficking in Mainland Southeast Asia Drug trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy CNRS-Prodig (Maps 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 25, 31) The Golden Triangle is the name given to the area of mainland Southeast Asia where most of the world‟s illicit opium has originated since the early 1950s and until 1990, before Afghanistan‟s opium production surpassed that of Burma. It is located in the highlands of the fan-shaped relief of the Indochinese peninsula, where the international borders of Burma, Laos, and Thailand, run. However, if opium poppy cultivation has taken place in the border region shared by the three countries ever since the mid-nineteenth century, it has largely receded in the 1990s and is now confined to the Kachin and Shan States of northern and northeastern Burma along the borders of China, Laos, and Thailand. -

INSIDE and Coerced to Change Statement 10D Editorials Cartoons Opinions Letters

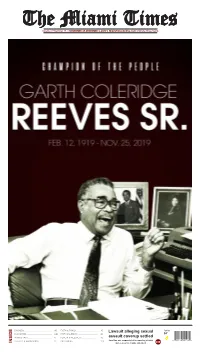

Volume 97 Number 15 | NOVEMBER 27-DECEMBER 3, 2019 | MiamiTimesOnline.com | Ninety-Three Cents BUSINESS ................................................. 8B FAITH & FAMILY ...................................... 7D Lawsuit alleging sexual Today CLASSIFIED ............................................. 11B FAITH CALENDAR ................................... 8D 84° IN GOOD TASTE ......................................... 1C HEALTH & WELLNESS ............................. 9D assault coverup settled LIFESTYLE HAPPENINGS ....................... 5C OBITUARIES ............................................. 12D Jane Doe was suspended after reporting attacks 8 90158 00100 0 INSIDE and coerced to change statement 10D Editorials Cartoons Opinions Letters VIEWPOINT BLACKS MUST CONTROL THEIR OWN DESTINY | NOVEMBER 27-DECEMBER 3, 2019 | MiamiTimesOnline.com MEMBER: National Newspaper Periodicals Postage Credo Of The Black Press Publisher Association paid at Miami, Florida Four Florida outrages: (ISSN 0739-0319) The Black Press believes that America MEMBER: The Newspaper POSTMASTER: Published Weekly at 900 NW 54th Street, can best lead the world from racial and Association of America Send address changes to Miami, Florida 33127-1818 national antagonism when it accords Subscription Rates: One Year THE MIAMI TIMES, The wealthy flourish, Post Office Box 270200 to every person, regardless of race, $65.00 – Two Year $120.00 P.O. Box 270200 Buena Vista Station, Miami, Florida 33127 creed or color, his or her human and Foreign $75.00 Buena Vista Station, Miami, FL Phone 305-694-6210 legal rights. Hating no person, fearing 7 percent sales tax for Florida residents 33127-0200 • 305-694-6210 the poor die H.E. SIGISMUND REEVES Founder, 1923-1968 no person, the Black Press strives to GARTH C. REEVES JR. Editor, 1972-1982 help every person in the firm belief that ith President Trump’s impeachment hearing domi- GARTH C. REEVES SR.