University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1.10 Linear Models in Business, Science, And

May 10, 2005 10:46 l57-ch01 Sheet number 92 Page number 92 cyan magenta yellow black 92 CHAPTER 1 Linear Equations in Linear Algebra 1.10 LINEAR MODELS IN BUSINESS, SCIENCE, AND ENGINEERING The mathematical models in this section are all linear; that is, each describes a prob- lem by means of a linear equation, usually in vector or matrix form. The first model concerns nutrition but actually is representative of a general technique in linear program- ming problems. The second model comes from electrical engineering. The third model introduces the concept of a linear difference equation, a powerful mathematical tool for WEB studying dynamic processes in a wide variety of fields such as engineering, ecology, economics, telecommunications, and the management sciences. Linear models are im- portant because natural phenomena are often linear or nearly linear when the variables involved are held within reasonable bounds. Also, linear models are more easily adapted for computer calculation than are complex nonlinear models. As you read about each model, pay attention to how its linearity reflects some property of the system being modeled. May 10, 2005 10:46 l57-ch01 Sheet number 93 Page number 93 cyan magenta yellow black 1.10 Linear Models in Business, Science, and Engineering 93 Constructing a Nutritious Weight-Loss Diet WEB The formula for the Cambridge Diet, a popular diet in the 1980s, was based on years of research. A team of scientists headed by Dr. Alan H. Howard developed this diet at Cambridge University after more than eight years of clinical work with obese patients.1 The very low-calorie powdered formula diet combines a precise balance of carbohy- drate, high-quality protein, and fat, together with vitamins, minerals, trace elements, and electrolytes. -

Deception in Weight-Loss Advertising Workshop

DECEPTION IN WEIGHT-LOSS ADVERTISING WORKSHOP: Seizing Opportunities and Building Partnerships to Stop Weight-Loss Fraud A Federal Trade Commission Staff Report December 2003 Federal Trade Commission TIMOTHY J. MURIS, Chairman MOZELLE W. THOMPSON, Commissioner ORSON SWINDLE, Commissioner THOMAS B. LEARY, Commissioner PAMELA JONES HARBOUR, Commissioner This is a report of the Bureau of Consumer Protection of the Federal Trade Commission. The views expressed in this report are those of the staff and do not necessarily represent the views of the Federal Trade Commission or any individual Commissioner. The Commission has voted to authorize the staff to publish this report. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service Offi ce of the Surgeon General Rockville MD 20857 We are witnessing a growing epidemic of obesity in this country. This epidemic not only costs this nation over $117 billion a year, but it also steals 300,000 lives. Unfortunately, there is no miracle pill that can help Americans lose excess weight, so we have to rely on responsible behavior – including eating right and being physically active. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Decrease Overweight and Obesity, released in December 2001, called upon almost every segment of the public and private sectors to work together to help Americans make healthy eating and physical activity choices. By improving our nation’s “health literacy” we can ensure that Americans have the information and tools they need to make effective decisions that will improve their overall health and lead to longer, healthier lives. The media can play an important role in educating consumers by providing accurate information about weight loss programs and weight management products. -

I Did It! on the Cambridge Diet Meal-Replacement Skip Breakfast – a Sugar-Free Cereal to a Few Songs

healthywellbeing TRIED How can I diet and prepare for pregnancy? & Hannah Fox tries: teSteD... I’m 35, overweight by about for fruit mid-morning, then a lunch of GI Jane Bootcamp 4st, and have been trying to get pitta stuffed with salad and houmous. Amanda’s Crawling out in age, background and fitness level Qpregnant for over a year. My GP A yogurt and a handful of almonds make of bed at – but we were encouraged to act like says I need to lose weight, but how can a great mid-afternoon snack, and choose The golden rule with l Work out why you 5.30am to a team and drive each other on. The I do this and get my body ready for a dinner of a lean protein like tofu in a losing weight is to focus have overeaten in the the shouts PTIs were supportive, keeping us pregnancy at the same time? vegetable-rich stir-fry. Best of luck! on what you want to past. Maybe it is simply and whistles going so that we got the most out YES achieve. Try these tips because you love food of two Royal of it, but never forcing us to do Amanda says: Losing weight Nicki says: To lose weight safely and to help you get to your or perhaps something in Marine physical training instructors anything we couldn’t manage. The before trying to conceive will steadily before conceiving, your primary goal weight and, your childhood sparked (PTIs), I wondered what I’d let activities were very varied, so we A enable your body, including your goal should be to burn calories by doing crucially, stay there: it off. -

Download GHD-014 Treating Malnutrition in Haiti with RUTF

C ASES IN G LOBAL H EALTH D ELIVERY GHD-014 APRIL 2011 Treating Malnutrition in Haiti with Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Foods In June of 2008, Dr. Joseline Marhone Pierre, the director of the Coordination Unit for the National Food and Nutrition Program of Haiti’s Ministry of Health and Population (MSPP), met with representatives from a consortium of three non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The consortium had completed a six month field trial during which it treated children with severe acute malnutrition (SAM) according to a community-based care model with ready-to-use therapeutic foods (RUTF). They were meeting to draft new national protocols for the treatment of severe acute malnutrition using results from the evaluation of the field trial. Contrary to international recommendations, Marhone believed that not only should severely acutely malnourished children be given RUTF, but so should moderately acutely malnourished children. This would mean procuring and delivering RUTF for over 100,000 children. The NGOs maintained that RUTFs were not designed for this use and that Marhone’s plan was not feasible given the rates of moderate and severe acute malnutrition in the country. How could the NGO consortium and Marhone reach an agreement on how to proceed? Overview of Haiti The Republic of Haiti was located on the western third of the Island of Quisqueya, called Hispaniola by the first Spanish settlers who arrived there in 1492. The Spanish ceded the western portion of the island to the French in 1697. With the labor of hundreds of thousands of slaves—estimated at 500,000 at the peak of slavery in the late eighteenth century—the French turned Haiti into the “Jewel of the Antilles,” a leading exporter of coffee, indigo, rum, and sugar. -

Deandist Complaint

9123220 B221274 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BEFORE FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION ________________________________________ ) In the Matter of ) ) DOCKET NO. C-3755 DEAN DISTRIBUTORS, INC., ) a corporation, doing business as ) ADVANCED HEALTH CARE SYSTEMS, ) CAMBRIDGE DIRECT SALES, and ) MEDIBASE. ) ________________________________________) COMPLAINT The Federal Trade Commission, having reason to believe that Dean Distributors, Inc., a corporation, through Advanced Health Care Systems, an operating division of Dean Distributors, Inc., has violated the provisions of the Federal Trade Commission Act, and it appearing to the Commission that a proceeding by it in respect thereof would be in the public interest, alleges: PARAGRAPH ONE: Respondent Dean Distributors, Inc. (hereinafter "respondent"), is incorporated in California, with its offices and principal place of business located at 1350 Bayshore Hwy., Suite 400, Burlingame, California 94010. Advanced Health Care Systems, an operating division of Dean Distributors, Inc., has its offices and principal place of business located at 2801 Salinas Hwy., Building F, Monterey, California 93940-6420. Advanced Health Care Systems also does business as Cambridge Direct Sales and as MediBase. PARAGRAPH TWO: Respondent advertises, offers for sale and sells, and otherwise promotes throughout the United States, weight loss and weight-loss maintenance services and products, including the "Food for Life Weight Management System" and "MediBase," and makes them available to the public through a multilevel distribution system and through direct sales to physicians and medical clinics. PARAGRAPH THREE: The Food for Life Weight Management System diet programs include the "Cambridge Diet Plan," the "Food for Life" programs, the "Maintain for Life" program, and related nutritional products. Certain Food for Life Weight Management Page 1 of 9 System diet programs provide 420 calories per day, obtained by drinking three formula drinks per day, and are referred to as very-low-calorie diet ("VLCD") programs. -

Identifying Low-Carb Dieter's Characteristics and Their Diet Practices During Business Travels

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2005 Identifying low-carb dieter's characteristics and their diet practices during business travels So Jung Lee University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Lee, So Jung, "Identifying low-carb dieter's characteristics and their diet practices during business travels" (2005). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 1839. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/g3x2-yh73 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IDENTIFYING LOW-CARB DIETERS’ CHARACTERISTICS AND THEIR DIET PRACTICES DURING BUSINESS TRAVELS by So Jung Lee Bachelor of Science Yonsei University 1999 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Hotel Administration William F. Harrah College of Hotel Administration Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas August 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1429713 Copyright 2005 by Lee, So Jung All rights reserved. -

The Effect of Very Low-Calorie Diets on Renal and Hepatic Outcomes: a Systematic Review

Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article SHORT REPORT The effect of very low-calorie diets on renal and hepatic outcomes: a systematic review Catherine Rolland1 Abstract: Very low-calorie diets (VLCDs) are an effective means by which to induce Alexandra Mavroeidi2 clinically significant weight loss. However, their acceptance by health care practitioners and Kelly L Johnston3 the public is generally lower than that for other nonsurgical weight loss methods. Whilst there is John Broom1,3 currently little evidence to suggest they have any detrimental effect on hepatic and renal health, data assessing these factors remain limited. We carried out a systematic review of the literature on 1Centre for Obesity Research and Epidemiology (CORE), Faculty of randomized controlled trials that had a VLCD component and that reported outcomes for hepatic Health and Social Care, Robert and renal health, published between January 1980 and December 2012. Cochrane criteria were fol- Gordon University, Aberdeen, lowed, and eight out of 196 potential articles met the inclusion criteria. A total of 548 participants Scotland, UK; 2School of Medical Sciences, College of Life Sciences and were recruited across the eight studies. All eight studies reported significant weight loss fol- For personal use only. Medicine, University of Aberdeen, lowing the VLCD. Changes in hepatic and renal outcomes were variable but generally led 3 Aberdeen, Scotland, UK; LighterLife to either no change or improvements in either of these. Due to the heterogeneity in the quality Ltd, Harlow, Essex, UK and methodology of the studies included, the effect of VLCDs on hepatic and renal outcomes remains unclear at this stage. -

Overview of Popular Diets.Indd

An Overview of Popular Diets By Jacqueline Jacques, ND Americans seemingly have a love affair with dieting. In the year 2000, American consumers spent $34.7 Diet (v. intr.): To eat and billion out-of-pocket dollars on weight-loss products and programs – a number that experts suspect drink according to continues to climb1. On any given day if you check out the New York Times best-seller list, you will a regulated system, likely fi nd at least two diet books in the top 10 list for non-fi ction. When I looked this week, it was especially so as to lose The Volumetrics Eating Plan by Barbara Rolls, PhD and The Extreme Fat Smash Diet by Ian K. Smith. weight. Wait a month, and these will likely be replaced by something new. – American Heritage Dictionary Since roughly two-thirds of the American public is either overweight or obese, the real question is: Do any of these plans result in the desired goal back on the dieter. Naturally then, the golden ticket of getting weight off and keeping it off? After all, everyone is looking for is the perfect program that will the advice always given to those who need to lose help people both lose weight and maintain weight-loss. weight is to diet and exercise. When this fails to So, those seeking the answer invest year after year in new produce the desired result, the blame is always put diet books and programs and new hope. Benefi ts to Diets Dieting Keys to Success What will follow here is a brief overview and review of a handful of popular diet systems. -

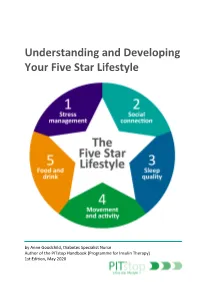

Understanding and Developing Your Five Star Lifestyle

Understanding and Developing Your Five Star Lifestyle by Anne Goodchild, Diabetes Specialist Nurse Author of the PITstop Handbook (Programme for Insulin Therapy) 1st Edition, May 2020 Dietary messages can seem confusing and conflicting. What you hear on television one week can be contradicted in a newspaper article the next. When it comes to Pre-diabetes and Type 2 diabetes, it’s important to be aware of up-to-date information and resources to help you make informed choices and set personal goals. This booklet is designed to help you consider your current lifestyle (day-to-day routine), including other aspects that may affect your health (stress management, social connection, sleep quality, movement and activity). You are encouraged to set a personal goal, but more importantly, develop a realistic action plan to help you achieve your goal. You can refer to the wide range of up-to-date advice and resources to help you develop your action plan. The 5-star lifestyle (figure1) allows us to reflect on the different aspects that can affect our health and day-to-day routine. When considering your own 5-star lifestyle it’s important to remember that the five elements are interlinked and can affect each other. Also, consider that some people may place greater importance on certain elements. For example, social connection may be important to you but a family member may be content with their own company. Joe’s example highlights how stress can affect other aspects of his daily routine, ultimately affecting his health. Figure 1: The Five Star Lifestyle Joe noticed that he felt stressed at work since moving departments last year. -

Detox & Weight Loss Tips

DETOX & WEIGHT LOSS TIPS E-BOOK PROUDLY SUPPORTING AUSTRALIANS SINCE 1947 03 CONTENT Introduction 03 Common Causes of Weight Gain 04 Say No to Toxins 06 Pros and Cons of Popular Diets 09 Are all Sugars Bad? 14 Junk Food Cycle 18 Diet Tips for Detox and Weight Loss 19 The New Food Pyramid? 22 Recipes 23 Exercise Tips 28 Yoga for Detox and Weight Loss 30 Growing Herbs at Home for Detox and Weight Loss 31 Weight Loss and Detox Supplements 33 Online Links 36 PROUDLY SUPPORTING AUSTRALIANS SINCE 1947 03 INTRODUCTION There comes a moment when your clothes seem a bit too tight (how did that happen?), you feel a bit sluggish or bloated, and it’s time to make some changes. You just know it! But, where to start? With a multitude of fad diets, meal replacements, products and detoxes being touted as the answer you’re looking for, it can be hard to sort fact from fiction, and decide what to do. In this e-book we aim to help clarify some common questions, debunk some myths and arm you with a number of simple tips you can choose from to help support whatever your goal is. Be it weight loss, detoxification or just boosting your level of health up a notch or two. After all, every little change can make a big difference over time and the changes you make help not only improve your quality of life and wellbeing, but helps those around you as you have more energy and enthusiasm and are less likely to get sick. -

International Registration Designating India Trade Marks Journal No: 1807 , 24/07/2017 Class 1

International Registration designating India Trade Marks Journal No: 1807 , 24/07/2017 Class 1 Priority claimed from 07/12/2016; Application No. : VA 2016 02949 ;Denmark 3563384 15/02/2017 [International Registration No. : 1345901] Novozymes A/S Krogshøjvej 36 DK-2880 Bagsværd Denmark Proposed to be Used IR DIVISION Enzymes for use in the fats and oils industries. 7575 Trade Marks Journal No: 1807 , 24/07/2017 Class 1 3564207 27/02/2017 [International Registration No. : 1346830] WANHUA CHEMICAL GROUP CO., LTD. No. 17, Tianshan Road, Yeda, Yantai City 264006 Shandong Province China Proposed to be Used IR DIVISION Dressing and finishing preparations for textiles; textile-brightening chemicals; stain-preventing chemicals for use on fabrics; textile-waterproofing chemicals; epoxy resins, unprocessed; synthetic resins, unprocessed; polyurethane. 7576 Trade Marks Journal No: 1807 , 24/07/2017 Class 1 Priority claimed from 23/11/2016; Application No. : 016076374 ;European Union 3565425 01/03/2017 [International Registration No. : 1345865] Italmatch Chemicals S.p.A. Via Magazzini del Cotone, 17 Modulo 4 I-16128 Genova Italy Proposed to be Used IR DIVISION Chemical additives used in industry, in particular chemical additives used in the production of plastics, coatings, paints and ink; chemical additives used in the production of lubricating oils, greases and adhesives. 7577 Trade Marks Journal No: 1807 , 24/07/2017 Class 1 Priority claimed from 13/09/2016; Application No. : 87169830 ;United States of America 3568169 13/03/2017 [International Registration No. : 1347597] Life Technologies Corporation 5781 Van Allen Way Carlsbad CA 92008 United States of America Proposed to be Used IR DIVISION Reagents, cell media, enzymes and assays for research. -

Crowdsourcing Personalized Weight Loss Diets

Crowdsourcing Personalized Weight Loss Diets Simo Hosio1, Niels van Berkel2, Jonas Oppenlaender1, Jorge Goncalves2 1University of Oulu, Finland 2The University of Melbourne, Australia ABSTRACT. Diet is a key aspect in losing weight. Yet choosing a suitable diet among the practically unlimited options out there remains a daunting task. To this end, we contribute The Diet Explorer: a lightweight system usable with an intuitive graphical user interface, that relies on aggregated human insights for assessing and recommending suitable weight loss diets. We compared the system’s performance against the de-facto online search engine, Google, in discovering personalised diets. Our results suggest that the system, bootstrapped using a public crowdsourcing platform, provides results comparable to those of Google in terms of overall satisfaction, relevance, and trustworthiness. However, The Diet Explorer was perceived as significantly faster than Google for discovering diets. Finally, this paper contributes an open-source version of the system, re-implemented as a WordPress plugin for the scientific community to use and modify for their own purposes. Keywords: Crowdsourcing, Health-Information, Personalised Recommendations, Systems Evaluation INTRODUCTION Obesity is a growing health problem around the world and is described as a global epidemic by the World Health Organization (WHO). Not only is being overweight a psychologically sensitive issue, but it has been shown to negatively affect health in a plethora of ways, such as accelerating ageing or increasing the risk of diabetes and heart conditions. Examining the issue strictly through the academic lens, two aspects matter in losing weight: diet and exercise. However, previous work has shown that the former is substantially more important [1].