The Objectification of Women in Comics Kyra Nelson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magazines V17N9.Qxd

Feb COF C1:Customer 1/6/2012 2:54 PM Page 1 ORDERS DUE th 18FEB 2012 FEB E COMIC H T SHOP’S CATALOG 02 FEBRUARY COF Apparel Shirt Ad:Layout 1 1/11/2012 1:45 PM Page 1 DC HEROES: “SUPER POWERS” Available only TURQUOISE T-SHIRT from your local comic shop! PREORDER NOW! SPIDER-MAN: DEADPOOL: “POOL SHOT” PLASTIC MAN: “DOUBLE VISION” BLACK T-SHIRT “ALL TIED UP” BURGUNDY T-SHIRT PREORDER NOW! CHARCOAL T-SHIRT PREORDER NOW! PREORDER NOW! COF Gem Page February:gem page v18n1.qxd 1/11/2012 1:29 PM Page 1 STAR WARS: MASS EFFECT: BLOOD TIES— HOMEWORLDS #1 BOBA FETT IS DEAD #1 DARK HORSE COMICS (OF 4) DARK HORSE COMICS WONDER WOMAN #8 DC COMICS RICHARD STARK’S PARKER: STIEG LARSSON’S THE SCORE HC THE GIRL WITH THE DRAGON IDW PUBLISHING TATTOO SPECIAL #1 DC COMICS / VERTIGO SECRET #1 IMAGE COMICS AMERICA’S GOT POWERS #1 (OF 6) AVENGERS VS. X-MEN: IMAGE COMICS VS. #1 (OF 6) MARVEL COMICS COF FI page:FI 1/12/2012 10:00 AM Page 1 FEATURED ITEMS COMICS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Girl Genius Volume 11: Agatha Heterodyne and the Hammerless Bell TP/HC G AIRSHIP ENTERTAINMENT Strawberry Shortcake Volume 1: Berry Fun TP G APE ENTERTAINMENT Bart Simpson‘s Pal, Milhouse #1 G BONGO COMICS Fanboys Vs. Zombies #1 G BOOM! STUDIOS 1 1 Roger Langridge‘s Snarked! Volume 1 TP G BOOM! STUDIOS/KABOOM! Lady Death Origins: Cursed #1 G BOUNDLESS COMICS The Shadow #1 G D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT The Shadow: Blood & Judgment TP G D. -

Katie Wackett Honours Final Draft to Publish (FILM).Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Female Subjectivity, Film Form, and Weimar Aesthetics: The Noir Films of Robert Siodmak by Kathleen Natasha Wackett A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ARTS IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF BA HONOURS IN FILM STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION, MEDIA, AND FILM CALGARY, ALBERTA APRIL, 2017 © Kathleen Natasha Wackett 2017 Abstract This thesis concerns the way complex female perspectives are realized through the 1940s noir films of director Robert Siodmak, a factor that has been largely overseen in existing literature on his work. My thesis analyzes the presentation of female characters in Phantom Lady, The Spiral Staircase, and The Killers, reading them as a re-articulation of the Weimar New Woman through the vernacular of Hollywood cinema. These films provide a representation of female subjectivity that is intrinsically connected to film as a medium, as they deploy specific cinematic techniques and artistic influences to communicate a female viewpoint. I argue Siodmak’s iterations of German Expressionist aesthetics gives way to a feminized reading of this style, communicating the inner, subjective experience of a female character in a visual manner. ii Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without my supervisor Dr. Lee Carruthers, whose boundless guidance and enthusiasm is not only the reason I love film noir but why I am in film studies in the first place. I’d like to extend this grateful appreciation to Dr. Charles Tepperman, for his generous co-supervision and assistance in finishing this thesis, and committee member Dr. Murray Leeder for taking the time to engage with my project. -

Brilliant Corners: Approaches to Jazz and Comics

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pillai, N. and Priego, E. (2016). Brilliant Corners: Approaches to Jazz and Comics. The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship, 6(1), 12.. doi: 10.16995/cg.92 This is the published version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/15255/ Link to published version: 10.16995/cg.92 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Nicolas Pillai and Ernesto Priego, ‘Brilliant Corners: THE COMICS GRID Approaches to Jazz and Comics’ (2016) 6(1): 12 Journal of comics scholarship The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.16995/cg.92 EDITORIAL Brilliant Corners: Approaches to Jazz and Comics Nicolas Pillai1 and Ernesto Priego2 1 Birmingham City University, UK 2 City University London, UK Corresponding author: Nicolas Pillai ([email protected]) The call for papers Brilliant Corners: Approaches to Jazz and Comics was published on 30 July 2015. -

En 2016, De La Mano De La Actriz Margot Robbie Y De La Película

EDITORIAL n 2016, de la mano de la actriz Margot Joker, tendrá un papel destacado en la línea DC Robbie y de la película Escuadrón Suicida, Black Label durante el primer semestre del año, EHarley Quinn, que para muchos lectores ya mediante varios proyectos entre los que destaca era uno de los personajes más especiales del Harleen, de Stjepan Šejić, una reimaginación del Universo DC, traspasaba el mundo de las viñetas origen del personaje, ideal para nuevos lectores. para convertirse en un icono pop que poco a poco se ha instalado en el imaginario popular, Aves de Presa ocupa gran parte de los marcando a toda una generación. La película contenidos que veréis en las siguientes páginas, Aves de presa (y la fantabulosa emancipación pero hay más. En 2020 iniciamos una nueva de Harley Quinn), dirigida por Cathy Yan, que se etapa en lo que se refiere a títulos inéditos de DC ha estrenado este mes de febrero en nuestro Comics que se publican en la revista. A partir de país, supone un paso más en la meteórica este número encontraréis dos series limitadas carrera de Robbie y de la doctora Harleen muy esperadas: Superman: Arriba, en el cielo, de Quinzel. Por supuesto, nosotros no somos Tom King y Andy Kubert, y Universo Batman, de ajenos al fenómeno. Repasamos las claves del Brian Michael Bendis y Nick Derington. Los iconos film y hablamos de sus protagonistas y de sus más conocidos. Los autores del momento. Todos versiones comiqueras, con recomendaciones reunidos para hacer de ECC Cómics algo todavía de aventuras que podéis encontrar ya mismo más especial, una cita mensual imprescindible en vuestra tienda favorita. -

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman

Department of Political Science Chair of Gender Politics Wonder Woman and Captain Marvel as Representation of Women in Media Sara Mecatti Prof. Emiliana De Blasio Matr. 082252 SUPERVISOR CANDIDATE Academic Year 2018/2019 1 Index 1. History of Comic Books and Feminism 1.1 The Golden Age and the First Feminist Wave………………………………………………...…...3 1.2 The Early Feminist Second Wave and the Silver Age of Comic Books…………………………....5 1.3 Late Feminist Second Wave and the Bronze Age of Comic Books….……………………………. 9 1.4 The Third and Fourth Feminist Waves and the Modern Age of Comic Books…………...………11 2. Analysis of the Changes in Women’s Representation throughout the Ages of Comic Books…..........................................................................................................................................................15 2.1. Main Measures of Women’s Representation in Media………………………………………….15 2.2. Changing Gender Roles in Marvel Comic Books and Society from the Silver Age to the Modern Age……………………………………………………………………………………………………17 2.3. Letter Columns in DC Comics as a Measure of Female Representation………………………..23 2.3.1 DC Comics Letter Columns from 1960 to 1969………………………………………...26 2.3.2. Letter Columns from 1979 to 1979 ……………………………………………………27 2.3.3. Letter Columns from 1980 to 1989…………………………………………………….28 2.3.4. Letter Columns from 19090 to 1999…………………………………………………...29 2.4 Final Data Regarding Levels of Gender Equality in Comic Books………………………………31 3. Analyzing and Comparing Wonder Woman (2017) and Captain Marvel (2019) in a Framework of Media Representation of Female Superheroes…………………………………….33 3.1 Introduction…………………………….…………………………………………………………33 3.2. Wonder Woman…………………………………………………………………………………..34 3.2.1. Movie Summary………………………………………………………………………...34 3.2.2.Analysis of the Movie Based on the Seven Categories by Katherine J. -

Cast Biographies Chris Mann

CAST BIOGRAPHIES CHRIS MANN (The Phantom) rose to fame as Christina Aguilera’s finalist on NBC’s The Voice. Since then, his debut album, Roads, hit #1 on Billboard's Heatseekers Chart and he starred in his own PBS television special: A Mann For All Seasons. Chris has performed with the National Symphony for President Obama, at Christmas in Rockefeller Center and headlined his own symphony tour across the country. From Wichita, KS, Mann holds a Vocal Performance degree from Vanderbilt University and is honored to join this cast in his dream role. Love to the fam, friends and Laura. TV: Ellen, Today, Conan, Jay Leno, Glee. ChrisMannMusic.com. Twitter: @iamchrismann Facebook.com/ChrisMannMusic KATIE TRAVIS (Christine Daaé) is honored to be a member of this company in a role she has always dreamed of playing. Previous theater credits: The Most Happy Fella (Rosabella), Titanic (Kate McGowan), The Mikado (Yum- Yum), Jekyll and Hyde (Emma Carew), Wonderful Town (Eileen Sherwood). She recently performed the role of Cosette in Les Misérables at the St. Louis MUNY alongside Norm Lewis and Hugh Panero. Katie is a recent winner of the Lys Symonette award for her performance at the 2014 Lotte Lenya Competition. Thanks to her family, friends, The Mine and Tara Rubin Casting. katietravis.com STORM LINEBERGER (Raoul, Vicomte de Chagny) is honored to be joining this new spectacular production of The Phantom of the Opera. His favorite credits include: Lyric Theatre of Oklahoma: Disney’s The Little Mermaid (Prince Eric), Les Misérables (Feuilly). New London Barn Playhouse: Les Misérables (Enjolras), Singin’ in the Rain (Roscoe Dexter), The Music Man (Jacey Squires, Quartet), The Student Prince (Karl Franz u/s). -

Postfeminism in Female Team Superhero Comic Books by Showing the Opposite of The

POSTFEMINISM IN FEMALE TEAM SUPERHERO COMIC BOOKS by Elliott Alexander Sawyer A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Communication The University of Utah August 2014 Copyright © Elliott Alexander Sawyer 2014 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF THESIS APPROVAL The following faculty members served as the supervisory committee chair and members for the thesis of________Elliott Alexander Sawyer__________. Dates at right indicate the members’ approval of the thesis. __________Robin E. Jensen_________________, Chair ____5/5/2014____ Date Approved _________Sarah Projansky__________________, Member ____5/5/2014____ Date Approved _________Marouf Hasian, Jr.________________, Member ____5/5/2014____ Date Approved The thesis has also been approved by_____Kent A. Ono_______________________ Chair of the Department/School/College of_____Communication _______ and by David B. Kieda, Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT Comic books are beginning to be recognized for their impact on society because they inform, channel, and critique cultural norms. This thesis investigates how comic books interact and forward postfeminism. Specifically, this thesis explores the ways postfeminism interjects itself into female superhero team comic books. These comics, with their rosters of only women, provide unique perspectives on how women are represented in comic books. Additionally, the comics give insight into how women bond with one another in a popular culture text. The comics critiqued herein focus on transferring postfeminist ideals in a team format to readers, where the possibilities for representing powerful connections between women are lost. Postfeminist characteristics of consumption, sexual freedom, and sexual objectification are forwarded in the comic books, while also promoting aspects of racism. -

The Portrayal of Women in American Superhero Comics By: Esmé Smith Junior Research Project Seminar

Hidden Heroines: The Portrayal of Women in American Superhero Comics By: Esmé Smith Junior Research Project Seminar Introduction The first comic books came out in the 1930s. Superhero comics quickly became one of the most popular genres. Today, they remain incredibly popular and influential. I have been interested in superhero comics for several years now, but one thing I often noticed was that women generally had much smaller roles than men and were also usually not as powerful. Female characters got significantly less time in the story devoted to them than men, and most superhero teams only had one woman, if they had any at all. Because there were so few female characters it was harder for me to find a way to relate to these stories and characters. If I wanted to read a comic that centered around a female hero I had to spend a lot more time looking for it than if I wanted to read about a male hero. Another thing that I noticed was that when people talk about the history of superhero comics, and the most important and influential superheroes, they almost only talk about male heroes. Wonder Woman was the only exception to this. This made me curious about other influential women in comics and their stories. Whenever I read about the history of comics I got plenty of information on how the portrayal of superheroes changed over time, but it always focused on male heroes, so I was interested in learning how women were portrayed in comics and how that has changed. -

Ebook Download Garth Ennis Red Team: Volume 1

GARTH ENNIS RED TEAM: VOLUME 1 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Garth Ennis,Craig Cermak | 152 pages | 08 Apr 2014 | Dynamic Forces Inc | 9781606904435 | English | Runnemede, United States Garth Ennis Red Team: Volume 1 PDF Book Weekly Auction ends Monday October 26! That is, until Trudy, in a fit of rage combined with panic, accidentally kills a man who was forcing himself on his girlfriend. Ennis shortly after began to write for Crisis' parent publication, AD. Learn more or Continue. This is what. Available Stock Add to want list This item is not in stock. From Batman onward, the comic world has been over saturated not just with capes taking justice into their own hands but, innumerable fictional policemen too struggling with harsh criminal dilemmas than only seem to beg for an itchy trigger finger. Unfortunately, they get blindsighted, with Duke and George being killed first. May 16, Adrian Bloxham rated it liked it. This story of a team of detectives is gripping. Told after the fact, the story focuses on the why's and the how's, as the Red Team takes it upon themselves to take down select individuals to make the world better. Really enjoyed this book. It spawned a sequel, For a Few Troubles More, a broad Belfast-based comedy featuring two supporting characters from Troubled Souls, Dougie and Ivor, who would later get their own American comics series, Dicks, from Caliber in , and several follow-ups from Avatar. Took you long enough, Garth! Garth Ennis writes a typically bloody tale of an elite anti- narcotics unit that, seeing one too many scumbags get out from under indictment, decides to kill a particularly egregious felon. -

SUPERGIRLS and WONDER WOMEN: FEMALE REPRESENTATION in WARTIME COMIC BOOKS By

SUPERGIRLS AND WONDER WOMEN: FEMALE REPRESENTATION IN WARTIME COMIC BOOKS by Skyler E. Marker A Master's paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina May, 2017 Approved by: ________________________ Rebecca Vargha Skyler E. Marker. Supergirls and Wonder Women: Female Representation in Wartime Comics. A Master's paper for the M.S. in L.S. degree. May, 2017. 70 pages. Advisor: Rebecca Vargha This paper analyzes the representation of women in wartime era comics during World War Two (1941-1945) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (2001-2010). The questions addressed are: In what ways are women represented in WWII era comic books? What ways are they represented in Post 9/11 comic books? How are the representations similar or different? In what ways did the outside war environment influence the depiction of women in these comic books? In what ways did the comic books influence the women in the war outside the comic pages? This research will closely examine two vital periods in the publications of comic books. The World War II era includes the genesis and development to the first war-themed comics. In addition many classic comic characters were introduced during this time period. In the post-9/11 and Operation Iraqi Freedom time period war-themed comics reemerged as the dominant format of comics. Headings: women in popular culture-- United States-- History-- 20th Century Superhero comic books, strips, etc.-- History and criticism World War, 1939-1945-- Women-- United States Iraq war (2003-2011)-- Women-- United States 1 I. -

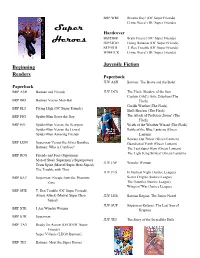

Super Heroes

BRP WRE Bizarro Day! (DC Super Friends) Crime Wave! (DC Super Friends) Super Hardcover B8555BR Brain Freeze! (DC Super Friends) Heroes H2934GO Going Bananas (DC Super Friends) S5395TR T. Rex Trouble (DC Super Friends) W9441CR Crime Wave! (DC Super Friends) Juvenile Fiction Beginning Readers Paperback JUV ASH Batman: The Brave and the Bold Paperback BRP ASH Batman and Friends JUV DCS The Flash: Shadow of the Sun Captain Cold’s Artic Eruption (The BRP BRI Batman Versus Man-Bat Flash) Gorilla Warfare (The Flash) BRP ELI Flying High (DC Super Friends) Shell Shocker (The Flash) BRP FIG Spider-Man Saves the Day The Attack of Professor Zoom! (The Flash) BRP HIL Spider-Man Versus the Scorpion Wrath of the Weather Wizard (The Flash) Spider-Man Versus the Lizard Battle of the Blue Lanterns (Green Spider-Man Amazing Friends Lantern) Beware Our Power (Green Lantern) BRP LEM Superman Versus the Silver Banshee Guardian of Earth (Green Lantern) Batman: Who is Clayface? The Last Super Hero (Green Lantern) The Light King Strikes! (Green Lantern) BRP ROS Friends and Foes (Superman) Man of Steel: Superman’s Superpowers JUV JAF Wonder Woman Team Spirit (Marvel Super Hero Squad) The Trouble with Thor JUV JUS In Darkest Night (Justice League) BRP SAZ Superman: Escape from the Phantom Secret Origins (Justice League) Zone The Gauntlet (Justice League) Wings of War (Justice League) BRP SHE T. Rex Trouble (DC Super Friends) Aliens Attack (Marvel Super Hero JUV LER Batman Begins: The Junior Novel Squad) JUV SUP Superman Returns: The Last Son of BRP STE I Am Wonder -

“Justice League Detroit”!

THE RETRO COMICS EXPERIENCE! t 201 2 A ugus o.58 N . 9 5 $ 8 . d e v r e s e R s t h ® g i R l l A . s c i m o C C IN THE BRONZE AGE! D © & THE SATELLITE YEARS M T a c i r e INJUSTICE GANG m A f o e MARVEL’s JLA, u g a e L SQUADRON SUPREME e c i t s u J UNOFFICIAL JLA/AVENGERS CROSSOVERS 7 A SALUTE TO DICK DILLIN 0 8 2 “PRO2PRO” WITH GERRY 6 7 7 CONWAY & DAN JURGENS 2 8 5 6 And the team fans 2 8 love to hate — 1 “JUSTICE LEAGUE DETROIT”! The Retro Comics Experience! Volume 1, Number 58 August 2012 Celebrating the Best Comics of the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR Michael “Superman”Eury PUBLISHER John “T.O.” Morrow GUEST DESIGNER Michael “BaTman” Kronenberg COVER ARTIST ISSUE! Luke McDonnell and Bill Wray . s c i m COVER COLORIST o C BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury .........................................................2 Glenn “Green LanTern” WhiTmore C D © PROOFREADER & Whoever was sTuck on MoniTor DuTy FLASHBACK: 22,300 Miles Above the Earth .............................................................3 M T . A look back at the JLA’s “Satellite Years,” with an all-star squadron of creators a c i r SPECIAL THANKS e m Jerry Boyd A Rob Kelly f o Michael Browning EllioT S! Maggin GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Unofficial JLA/Avengers Crossovers ................29 e u Rich Buckler g Luke McDonnell Never heard of these? Most folks haven’t, even though you might’ve read the stories… a e L Russ Burlingame Brad MelTzer e c i T Snapper Carr Mi ke’s Amazing s u J Dewey Cassell World of DC INTERVIEW: More Than Marvel’s JLA: Squadron Supreme ....................................33 e h T ComicBook.com Comics SS editor Ralph Macchio discusses Mark Gruenwald’s dictatorial do-gooders g n i r Gerry Conway Eri c Nolen- r a T s DC Comics WeaThingTon , ) 6 J.