Tigersoftrengganu.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills As of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct

Colgate Palmolive List of Mills as of June 2018 (H1 2018) Direct Supplier Second Refiner First Refinery/Aggregator Information Load Port/ Refinery/Aggregator Address Province/ Direct Supplier Supplier Parent Company Refinery/Aggregator Name Mill Company Name Mill Name Country Latitude Longitude Location Location State AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora Agroaceite Extractora Agroaceite Finca Pensilvania Aldea Los Encuentros, Coatepeque Quetzaltenango. Coatepeque Guatemala 14°33'19.1"N 92°00'20.3"W AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora del Atlantico Guatemala Extractora del Atlantico Extractora del Atlantico km276.5, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Champona, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°35'29.70"N 88°32'40.70"O AgroAmerica Agrocaribe Guatemala Agrocaribe S.A Extractora La Francia Guatemala Extractora La Francia Extractora La Francia km. 243, carretera al Atlantico,Aldea Buena Vista, Morales, izabal Izabal Guatemala 15°28'48.42"N 88°48'6.45" O Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - ASOCIACION AGROINDUSTRIAL DE PALMICULTORES DE SABA C.V.Asociacion (ASAPALSA) Agroindustrial de Palmicutores de Saba (ASAPALSA) ALDEA DE ORICA, SABA, COLON Colon HONDURAS 15.54505 -86.180154 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - Cooperativa Agroindustrial de Productores de Palma AceiteraCoopeagropal R.L. (Coopeagropal El Robel R.L.) EL ROBLE, LAUREL, CORREDORES, PUNTARENAS, COSTA RICA Puntarenas Costa Rica 8.4358333 -82.94469444 Oleofinos Oleofinos Mexico Pasternak - - CORPORACIÓN -

ASSESSMENT REPORT Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil Certification R S

PT. MUTUAGUNG LESTARI ASSESSMENT REPORT Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil Certification R S P O [√] Reduction Scope Certification Name of Management : KERTEH Palm Oil Mill, Felda Global Ventures (M) sdn Bhd Organisation subsidiary of FELDA Plantation Name : FASSB Kerteh Estate, FGVP Semaring 01 Estate, Kerteh 01 Estate, Kerteh 02 Estate, Kerteh 03 Estate, Kerteh 04 Estate, Kerteh 05 Estate and Kerteh 06 Estate Location : District of Ketengah Jaya, State of Terengganu, Malaysia Certificate Code : MUTU-RSPO/071 Date of Certificate Issue : 1 September 2015 Date of License Issue : 1 September 2015 Date of Certificate Expiry : 31 August 2020 Date of License Expiry : 31 August 2016 Assessment PT. Mutuagung Lestari Reviewed Approved Assessment Date Auditor by by ST-1 8 August 2014 Mahaswaran Maliyapan Mohan Thavarajah, Mohd Hairimi Ganapathy Taufik ST-2 26 – 30 October 2014 Mohd Ali, Nizam Abu Bakar, Ramasamy Margani Dinesh Nadarajah Reduction of Octo HPN Tony 18 November 2015 Taufik Margani Audit Scope Nainggolan Arifiarachman Assessment Approved by MUTUAGUNG LESTARI on: ST-2 7 December 2015 PT Mutuagung Lestari • Raya Bogor Km 33,5 Number 19 • Cimanggis • Depok 16953 • Indonesia Telephone (+62) (21) 8740202 • Fax (+62) (21) 87740745/6 • Email: [email protected] • www.mutucertification.com MUTU Certification Accredited by Accreditation Services International on March 12th, 2014 with registration number RSPO-ACC-007 PT. MUTUAGUNG LESTARI ASSESSMENT REPORT TABLE OF CONTENT FIGURE Figure 1. Location Map of Kerteh Complex 2 Figure 2 Operational -

TDM Plantation Sdn Bhd Head Office: Level 3, Bangunan UMNO Terengganu Lot 3224, Jalan Masjid Abidin 20100 Kuala Terengganu Terengganu, Malaysia

PF824 MSPO Public Summary Report Revision 0 (Aug 2017) MALAYSIAN SUSTAINABLE PALM OIL – ANNUAL SURVEILLANCE ASSESSMENT 1 Public Summary Report TDM Plantation Sdn Bhd Head Office: Level 3, Bangunan UMNO Terengganu Lot 3224, Jalan Masjid Abidin 20100 Kuala Terengganu Terengganu, Malaysia Certification Unit: Kemaman Palm Oil Mill & Plantations including Tebak Estate, Pelantoh Estate, Jernih Estate, Air Putih Estate, Gajah Mati Estate & MAIDAM Estate Location of Certification Unit: KM 121, Jerangau - Jabor Highway 24101 Kemaman, Terengganu, Malaysia Report prepared by: Mohamed Hidhir Zainal Abidin (Lead Auditor) Report Number: 8814293 Assessment Conducted by: BSI Services Malaysia Sdn Bhd, Unit 3, Level 10, Tower A The Vertical Business Suites, Bangsar South No. 8, Jalan Kerinchi 59200 Kuala Lumpur Tel +603 2242 4211 Fax +603 2242 4218 www.bsigroup.com Page 1 of 102 PF824 MSPO Public Summary Report Revision 0 (Aug 2017) TABLE of CONTENTS Page No Section 1: Executive Summary ........................................................................................ 3 1.1 Organizational Information and Contact Person ........................................................ 3 1.2 Certification Information ......................................................................................... 3 1.3 Location of Certification Unit ................................................................................... 4 1.4 Plantings & Cycle ................................................................................................... 4 1.6 Certified -

Mapping the Daily Rainfall Over an Ungauged Tropical Micro-Watershed: a Downscaling Algorithm Using GPM Data

water Article Mapping the Daily Rainfall over an Ungauged Tropical Micro-Watershed: A Downscaling Algorithm Using GPM Data Mohd. Rizaludin Mahmud 1,2,*, Aina Afifah Mohd Yusof 2, Md. Reba 1,2 and Mazlan Hashim 1,2 1 Geoscience & Digital Earth Centre, Research Institute for Sustainable Environment, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Johor Bharu, Johor 81310, Malaysia; [email protected] (M.N.M.R.); [email protected] (M.H.) 2 Deptartment of Geoinformation, Faculty of Built Environment & Surveying, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Johor Bharu, Johor 81310, Malaysia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 19 April 2020; Accepted: 8 June 2020; Published: 10 June 2020 Abstract: In this study, half-hourly Global Precipitation Mission (GPM) satellite precipitation data were downscaled to produce high-resolution daily rainfall data for tropical coastal micro-watersheds (100–1000 ha) without gauges or with rainfall data conflicts. Currently, daily-scale satellite rainfall downscaling techniques rely on rain gauge data as corrective and controlling factors, making them impractical for ungauged watersheds or watersheds with rainfall data conflicts. Therefore, we used high-resolution local orographic and vertical velocity data as proxies to downscale half-hourly GPM precipitation data (0.1◦) to high-resolution daily rainfall data (0.02◦). The overall quality of the downscaled product was similar to or better than the quality of the raw GPM data. The downscaled rainfall dataset improved the accuracy of rainfall estimates on the ground, with lower error relative to measured rain gauge data. The average error was reduced from 41 to 27 mm/d and from 16 to 12 mm/d during the wet and dry seasons, respectively. -

Terengganu Bilangan Pelajar Bilangan Pekerja Luas Kaw. Sekolah

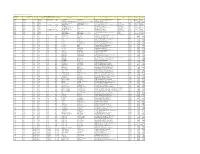

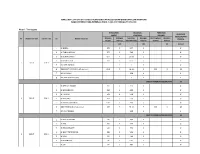

MAKLUMAT ZON UNTUK TENDER PERKHIDMATAN KEBERSIHAN BANGUNAN DAN KAWASAN BAGI KONTRAK YANG BERMULA PADA 1 JAN 2016 HINGGA 31 DIS 2018 Negeri : Terengganu ENROLMEN KELUASAN PENGHUNI BILANGAN MURID KAWASAN ASRAMA KESELURUHAN Bilangan Bilangan Luas Kaw. Bilangan Bil. Penghuni Bilangan BIL NAMA DAERAH NAMA ZON BIL NAMA SEKOLAH PEKERJA Pelajar Pekerja Sekolah (Ekar) Pekerja Asrama Pekerja (a) (b) (c) (a+b+c) 1 SK DARAU 372 3 2.97 2 5 2 SK TANAH MERAH 377 3 7.98 2 5 3 SK LUBUK KAWAH 654 4 10.50 2 6 4 SK ALOR KELADI 354 3 6.72 2 5 1 BESUT ZON 1 5 PKG SERI PAYONG 1 1 1 2 6 SMK BUKIT PAYONG (Sek & Asrama) 1315 8 16.16 3 300 2 13 7 KIP SK DARAU 1.00 1 1 8 KIP SMK BUKIT PAYONG 2 1 1 JUMLAH PEKERJA KESELURUHAN 38 1 SK BETING LINTANG 211 2 2.13 1 3 2 SK GONG BAYOR 553 4 4.98 1 5 3 SK TEMBILA 503 4 5.19 2 6 2 BESUT ZON 2 4 SK KELUANG 462 3 5.36 2 5 5 SK TENGKU MAHMUD 1043 6 7.61 2 8 6 SMK TEMBILA (Sek & Asrama) 495 3 35.10 5 200 2 10 7 KIP SMK TEMBILA 2.00 1 1 JUMLAH PEKERJA KESELURUHAN 38 1 SK KUALA KUBANG 115 2 4.94 1 3 2 SK JABI 514 4 4.94 1 5 3 SK FELDA SELASIH 110 2 7.91 2 4 4 SK BUKIT TEMPURONG 336 3 5.24 2 5 3 BESUT ZON 3 5 SK APAL 376 3 7.91 2 5 6 SK KERANDANG 545 4 6.92 2 6 7 SK OH 151 2 7.83 2 4 ENROLMEN KELUASAN PENGHUNI 3 BESUT ZON 3 BILANGAN MURID KAWASAN ASRAMA KESELURUHAN Bilangan Bilangan Luas Kaw. -

Public Summary Report Revision 8 (Mar /2019)

PF441 RSPO Public Summary Report Revision 8 (Mar /2019) RSPO PRINCIPLE AND CRITERIA – 1st Annual Surveillance Assessment (ASA1_1) Public Summary Report TDM Plantation Sdn Bhd Client company Address: Level 3, Bangunan UMNO Terengganu Lot 3224, Jalan Masjid Abidin 21000 Kuala Terengganu Terengganu, Malaysia Certification Unit: Kemaman Palm Oil Mill Location of Certification Unit: KM 121, Jerangau-Jabor Highway 24101 Kemaman Terengganu, Malaysia Page 1 of 119 PF441 RSPO Public Summary Report Revision 8 (Mar /2019) TABLE of CONTENTS Page No Section 1: Scope of the Certification Assessment ....................................................................... 4 1. Company Details ............................................................................................................... 4 2. Certification Information .................................................................................................... 4 3. Other Certifications ............................................................................................................ 4 4. Location(s) of Mill & Supply Bases ...................................................................................... 5 5. Description of Supply Base ................................................................................................. 5 6. Plantings & Cycle ............................................................................................................... 5 7. Certified Tonnage of FFB (Own Certified Scope) ................................................................. -

Retailers List - PETRON

Retailers List - PETRON RETAILER ADDRESS Esso - Abdul Majid Service Station Esso Jalan Sultan Ibrahim, 15050 Kota Bharu, Kelantan. 15050 Esso - ACS Petrol Station Lot 37009 KM 7, Jalan Sg Buloh, Bukit Cherakah, 40150 Shah Alam, 40150 Esso - Aktif Makmur Sdn Bhd No.11, Batu 1, Jalan Buloh Kasap, 85000 Segamat, Johor. 85000 Esso - Ambience Development Sdn Bhd Lot 11665, 11 3/4 Miles, Jln Kuala Kangsar, 31200 Kanthan, 31200 Esso - Anis Maju Enterprise Esso Durian Burung, KM 3 1/4, Durian Burung, 20050 Kuala Terengganu, 20050 Esso - ANZ Properties Sdn Bhd Jln Lada Hitam, Tmn Makmur, 86000 Kluang, 86000 Esso - Atlantic Express Sdn Bhd Lot 15536, Batu 59, Jln Kuantan, Mukim Pedah, 27000 Jerantut, 27000 Esso - Banting Petrol Service Station 183, Jalan Besar Banting, Kuala Langat, 42700 Selangor. 42700 Esso - BP Sin Huat Motor Car & Crane S/B 143, Jalan Tanjung Labuh, 83000 Batu Pahat. Johor. 83000 Esso - Bundusan SS Jln Bundusan, Penampang, 88300 Kota Kinabalu, Sabah. 88300 Esso - Carimin Enterprise Esso Service Station, Lt 35640, Jln Bt Unjur, Mukim Kelang, 41200 Esso - Cheong Yuen Service Station Jalan Besar, 35500 Bidor, Perak. 35500 Esso - Chin Chern Auto Services Sdn Bhd 127 BT 3 1/2, Jalan Klang Lama, 58000 KL. 58000 Esso - Chop Chin Leong 86, Jalan Kapar, 41400 Klang, Selangor. 41400 Esso - Chop Eng Huat 2, Main Road, Parit Raja, 86400 Batu Pahat, Johor. 86400 Esso - Chop Ghee Huat Sdn. Bhd. Esso Pusing S.S. Jalan Lahat, 31550 Pusing, 31550 Esso - Chop Kwong Sang Choy Esso Service Station Jalan Ketari, 28700 Bentong Pahang 28700 Esso - Chop Man Lee Loong 53, Jalan Pasar, 34000 Taiping, Perak. -

Senarai Pakar/Pegawai Perubatan Yang Mempunyai

SENARAI PAKAR/PEGAWAI PERUBATAN YANG MEMPUNYAI NOMBOR PENDAFTAARAN PEMERIKSAAN KESIHATAN BAKAL HAJI BAGI MUSIM HAJI 1439H / 2018M HOSPITAL & KLINIK KERAJAAN NEGERI TERENGGANU BIL NAMA DOKTOR ALAMAT TEMPAT BERTUGAS DAERAH 1. DR. MAIRA BT HASSAN KLINIK KESIHATAN MANIR KUALA TERENGGANU 2. DR. AZLIN BT AMAT KLINIK KESIHATAN HILIRAN KUALA TERENGGANU 3. DR. RAHIDA BT ABDUL RAZAK KLINIK KESIHATAN HILIRAN KUALA TERENGGANU 4. DR. MAZLINA BT ALIAS KLINIK KESIHATAN HILIRAN KUALA TERENGGANU 5. DR. JULIA BT MUSTAFFA KLINIK KESIHATAN HILIRAN KUALA TERENGGANU 6. DR. UMMI SABIQAH BT MOHD KLINIK KESIHATAN HILIRAN KUALA TAHAR TERENGGANU SENARAI PAKAR/PEGAWAI PERUBATAN YANG MEMPUNYAI NOMBOR PENDAFTAARAN PEMERIKSAAN KESIHATAN BAKAL HAJI BAGI MUSIM HAJI 1439H / 2018M HOSPITAL & KLINIK KERAJAAN NEGERI TERENGGANU BIL NAMA DOKTOR ALAMAT TEMPAT BERTUGAS DAERAH 7. DR. SITI TAHIRAH BINTI KLINIK KESIHATAN HILIRAN KUALA MAHMUD TERENGGANU 8. DR. NOOR AMIRA BT MOHD KLINIK KESIHATAN HILIRAN KUALA ADNAN TERENGGANU 9. DR. 'ATHIRAH AZ-ZAHRA BT ABU KLINIK KESIHATAN HILIRAN KUALA BAKAR TERENGGANU 10. DR. SITI MARAHAINI BT KLINIK KESIHATAN MANIR KUALA MAHAMED RUSDI TERENGGANU 11. DR. AZHAN BIN HAMDAN KLINIK KESIHATAN MANIR KUALA TERENGGANU 12. DR. MOHD AZHAR BIN ABD AZIZ KLINIK KESIHATAN MANIR KUALA TERENGGANU SENARAI PAKAR/PEGAWAI PERUBATAN YANG MEMPUNYAI NOMBOR PENDAFTAARAN PEMERIKSAAN KESIHATAN BAKAL HAJI BAGI MUSIM HAJI 1439H / 2018M HOSPITAL & KLINIK KERAJAAN NEGERI TERENGGANU BIL NAMA DOKTOR ALAMAT TEMPAT BERTUGAS DAERAH 13. DR. NORFAHIDA BT CHE MAT KLINIK KESIHATAN MANIR KUALA TERENGGANU 14. DR. NOR AFIDAH BT MAT KLINIK KESIHATAN IBU & ANAK KUALA YAACOB AIR JERNIH TERENGGANU 15. DR. ZALEHA BINTI JUSOH KLINIK KESIHATAN MARANG MARANG 16. DR. MAZLINAH BINTI MUDA KLINIK KESIHATAN MARANG MARANG 17. -

Codonoboea (Gesneriaceae) in Terengganu, Peninsular Malaysia, Including Three New Species

A peer-reviewed open-access journal PhytoKeys 131: 1–26 (2019) Codonoboea in Terengganu 1 doi: 10.3897/phytokeys.131.35944 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://phytokeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Codonoboea (Gesneriaceae) in Terengganu, Peninsular Malaysia, including three new species Ruth Kiew1, Chung-Lu Lim1 1 Forest Research Institute Malaysia, 52109 Kepong, Selangor, Malaysia Corresponding author: Ruth Kiew ([email protected]) Academic editor: Eric Roalson | Received 6 May 2019 | Accepted 29 July 2019 | Published 2 September 2019 Citation: Kiew R, Lim C-L (2019) Codonoboea (Gesneriaceae) in Terengganu, Peninsular Malaysia, including three new species. PhytoKeys 131: 1–26. https://doi.org/10.3897/phytokeys.131.35944 Abstract Of the 92 Codonoboea species that occur in Peninsular Malaysia, 20 are recorded from the state of Tereng- ganu, of which 9 are endemic to Terengganu including three new species, C. norakhirrudiniana Kiew, C. rheophytica Kiew and C. sallehuddiniana C.L.Lim, that are here described and illustrated. A key and checklist to all the Terengganu species are provided. The majority of species grow in lowland rain forest, amongst which C. densifolia and C. rheophytica are rheophytic. Only four grow in montane forest. The flora of Terengganu is still incompletely known, especially in the northern part of the state and in moun- tainous areas and so, with botanical exploration, more new species can be expected in this speciose genus. Keywords Checklist, key, new species, Codonoboea norakhirrudiniana, Codonoboea rheophytica and Codonoboea salle- huddiniana, endemism Introduction The centre of diversity of the genusCodonoboea (Gesneriaceae) is Peninsular Malaysia from where at least 92 species of the 140 named species are known (Lim and Kiew 2014). -

Research Pamphlet No. 131 PENINSULAR MALAYSIA Botanical Gazetteer for PENINSULAR MALAYSIA

RP 131 Research Pamphlet No. 131 PENINSULAR MALAYSIA Botanical Gazetteer for PENINSULAR MALAYSIA PENINSULAR MALAYSIA This botanical gazetteer provides standardised locality names and their coordinates for plants that have been collected in Peninsular Malaysia in the last 150 years. The more than 2,800 localities listed in the Gazetteer are derived from herbarium specimens lodged in the Herbarium of the Forest Research Institute Malaysia (KEP), the Singapore Herbarium (SING) and botanical literature. M. Hamidah, L.S.L. Chua, M. Suhaida, W.S.Y. Yong & R. Kiew ISBN 978-967-5221-72-9 9 789675 221729 New pg i-v cip page.pmd 1 12/19/2011, 11:22 AM Produced with the financial support of MINISTRY OF SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION GOVERNMENT OF MALAYSIA New pg i-v cip page.pmd 2 12/19/2011, 11:22 AM Research Pamphlet No. 131 M. Hamidah L.S.L. Chua M. Suhaida W.S.Y. Yong R. Kiew Forest Research Institute Malaysia Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, Malaysia 2011 New pg i-v cip page.pmd 3 12/19/2011, 11:22 AM © Forest Research Institute Malaysia 2011 Date of Publication: 28th December 2011 All enquiries should be forwarded to: Director-General Forest Research Institute Malaysia 52109 Kepong Selangor Darul Ehsan Malaysia Tel: 603-6279 7000 Fax: 603-6273 1314 Homepage: http://www.frim.gov.my Perpustakaan Negara Malaysia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Botanical gazetteer for Peninsular Malaysia / M. Hamidah ... [et al.] Research pamphlet ; no. 131 ISBN 978-967-5221-72-9 1. Phytogeography--Malaysia. 2. Malaysia--Gazetteers. I. M. Hamidah. -

Toponymic Guidelines for Map and Other Editors

TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS For International Use GARIS PANDUAN TOPONIMI BAGI EDITOR PETA DAN LAIN-LAIN Untuk Kegunaan Antarabangsa MALAYSIA Malaysian National Committee on Geographical Names Jawatankuasa Kebangsaan Nama Geografi First Edition, 2017 Edisi Pertama, 2017 Table of Content Isi Kandungan 1. Introduction 5 1. Pengenalan 5 2. Language 6 2. Bahasa 6 2.1 General statement 6 2.1 Kenyataan umum 6 2.2 National and official language 6 2.2 Bahasa kebangsaan dan bahasa 6 2.3 A brief history of the Malay 6 rasmi language 2.3 Sejarah ringkas Bahasa Melayu 6 2.4 History of Malay as the national 6 2.4 Sejarah Bahasa Melayu sebagai 6 language Bahasa kebangsaan 3. Spelling and Pronunciation 8 3. Ejaan dan Sebutan 8 3.1 Spelling 8 3.1 Ejaan 8 3.1.1 Roman 8 3.1.1 Rumi 3.1.1a) Alphabet 8 3.1.1a) Abjad 8 3.1.1b) Vowels 9 3.1.1b) Huruf vokal 9 3.1.1c) Diphtongs 9 3.1.1c) Huruf diftong 9 3.1.1d) Consonants 10 3.1.1d) Huruf konsonan 10 3.1.1e) Spelling of geographical names 11 3.1.1e) Pengejaan nama geografi 11 3.1.2 Jawi 11 3.1.2 Jawi 11 3.1.2a) Writing, spelling and alphabet 12 3.1.2a) Tulisan, ejaan dan abjad 12 3.2 Pronunciation 14 3.2 Sebutan 14 3.2a) Pronunciation of proper names 14 3.2a) Sebutan nama khas 14 4. Dialects 16 4. Dialek 16 4.1 Johor Dialect 16 4.1 Dialek Johor 16 4.2 Kedah Dialect 16 4.2 Dialek Kedah 16 4.3 Perak Dialect 17 4.3 Dialek Perak 17 4.4 Pahang Dialect 17 4.4 Dialek Pahang 17 4.5 Kelantan Dialect 17 4.5 Dialek Kelantan 17 4.6 Terengganu Dialect 18 4.6 Dialek Terengganu 18 4.7 Negeri Sembilan Dialect 18 4.7 Dialek Negeri Sembilan 18 4.8 Sarawak Malay Dialect 19 4.8 Dialek Melayu Sarawak 19 4.9 Malay Languange in Sabah 19 4.9 Bahasa Melayu di Sabah 19 4.10 Dialect Kedayan 20 4.10 Dialek Kedayan 20 4.11 Brunei Malay Dialect 20 4.11 Dialek Melayu Brunei 20 4.12 Other languages 20 4.12 Bahasa-bahasa lain 20 5. -

TDM Plantation Sdn Bhd Head Office: Level 3, Bangunan UMNO Terengganu Lot 3224, Jalan Masjid Abidin 20100 Kuala Terengganu Terengganu, Malaysia

PF824 MSPO Public Summary Report Revision 0 (Aug 2017) MALAYSIAN SUSTAINABLE PALM OIL – ANNUAL SURVEILLANCE ASSESSMENT 1 Public Summary Report TDM Plantation Sdn Bhd Head Office: Level 3, Bangunan UMNO Terengganu Lot 3224, Jalan Masjid Abidin 20100 Kuala Terengganu Terengganu, Malaysia Certification Unit: Sungai Tong Palm Oil Mill & Plantations: Jaya Estate, Fikri Estate, Tayor Estate, Pelung Estate, Jerangau Estate and Pinang Emas Estate Location of Certification Unit: Kilang Kelapa Sawit Sungai Tong, Lot 7663, Batu 23, Jalan Kuala Terengganu-Kota Bharu, 21500 Setiu, Terengganu, Malaysia Report prepared by: Hafriazhar Mohd Mokhtar (Lead Auditor) Report Number: Assessment Conducted by: BSI Services Malaysia Sdn Bhd, Unit 3, Level 10, Tower A The Vertical Business Suites, Bangsar South No. 8, Jalan Kerinchi 59200 Kuala Lumpur Tel +603 2242 4211 Fax +603 2242 4218 www.bsigroup.com Page 1 of 90 PF824 MSPO Public Summary Report Revision 0 (Aug 2017) TABLE of CONTENTS Page No Section 1: Executive Summary ........................................................................................ 3 1.1 Organizational Information and Contact Person ........................................................ 3 1.2 Certification Information ......................................................................................... 3 1.3 Location of Certification Unit ................................................................................... 4 1.4 Plantings & Cycle ..................................................................................................