MERCER COUNTY Act 167 Stormwater Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lawrence County

LAWRENCE COUNTY START BRIDGE SD MILES PROGRAM IMPROVEMENT TYPE TITLE DESCRIPTION COST PERIOD COUNT COUNT IMPROVED Bridge restoration on State Route 4004 (Harbor/Edinburg Road) over Shenango BASE Bridge Rehabilitation Harbor/Edinburg Bridge River in Union and Neshannock Townships 3 $ 2,500,000 1 1 0 Bridge replacement on PA 65 (Woodside Avenue ) over Squaw Run in Wayne BASE Bridge Replacement Woodside Avenue Bridge Township 1 $ 1,100,000 1 1 0 Bridge rehabilitation on PA 288 (Wampum Avenue ) over B&P Railroad in Wayne BASE Bridge Rehabilitation Wampum Avenue Bridge Township 2 $ 7,500,000 1 1 0 Bridge replacement on PA 65 (Second Street) over B & P Railroad in the City of BASE Bridge Replacement PA 65 (Second Street) Bridge Ellwood 2 $ 6,200,000 1 1 0 BASE Bridge Rehabilitation Pulaski Road Bridge Bridge rehabilitation on Pulaski Road over Deer Creek in Pulaski Township 3 $ 1,000,000 1 1 0 Bridge replacement on State Route 2001 (Savannah Road) over McKee Run in BASE Bridge Replacement Savannah Road Bridge over McKee Run Shenango Township 3 $ 1,500,000 1 1 0 Bridge replacement on State Route 3001 (South Main Street) over Branch of BASE Bridge Replacement South Main Street Bridge over Branch of Hickory Run Hickory Run in Bessemer Borough 3 $ 2,000,000 1 1 0 Bridge rehabilitation on State Route 1015 (Liberty Road) over Jamison Run Branch BASE Bridge Rehabilitation Liberty Road Bridge in Plain Grove Township 3 $ 1,100,000 1 1 0 Superstructure replacement on Hemmerle Road over Beaver River Tributary in BASE Bridge Rehabilitation Hemmerle Road -

Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021 Length County of Mouth Water Trib To Wild Trout Limits Lower Limit Lat Lower Limit Lon (miles) Adams Birch Run Long Pine Run Reservoir Headwaters to Mouth 39.950279 -77.444443 3.82 Adams Hayes Run East Branch Antietam Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.815808 -77.458243 2.18 Adams Hosack Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.914780 -77.467522 2.90 Adams Knob Run Birch Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.950970 -77.444183 1.82 Adams Latimore Creek Bermudian Creek Headwaters to Mouth 40.003613 -77.061386 7.00 Adams Little Marsh Creek Marsh Creek Headwaters dnst to T-315 39.842220 -77.372780 3.80 Adams Long Pine Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Long Pine Run Reservoir 39.942501 -77.455559 2.13 Adams Marsh Creek Out of State Headwaters dnst to SR0030 39.853802 -77.288300 11.12 Adams McDowells Run Carbaugh Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.876610 -77.448990 1.03 Adams Opossum Creek Conewago Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.931667 -77.185555 12.10 Adams Stillhouse Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.915470 -77.467575 1.28 Adams Toms Creek Out of State Headwaters to Miney Branch 39.736532 -77.369041 8.95 Adams UNT to Little Marsh Creek (RM 4.86) Little Marsh Creek Headwaters to Orchard Road 39.876125 -77.384117 1.31 Allegheny Allegheny River Ohio River Headwater dnst to conf Reed Run 41.751389 -78.107498 21.80 Allegheny Kilbuck Run Ohio River Headwaters to UNT at RM 1.25 40.516388 -80.131668 5.17 Allegheny Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Headwaters to Mouth 40.554253 -80.206802 -

Open Shan Li Master Thesis.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School School of Forest Resources AN EXAMINATION OF PETROMYZONTIDAE IN PENNSYLVANIA A Thesis in Wildlife and Fisheries Science by Shan Li 2012 Shan Li Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science May 2012 The thesis of Shan Li was reviewed and approved* by the following: Jay R. Stauffer Distinguished Professor of Ichthyology Thesis Advisor Paola C. Ferreri Associate Professor of Fisheries Management Donna J. Peuquet Professor of GIScience Jay R. Stauffer Distinguished Professor of Ichthyology Chair of Graduate Program *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT Lampreys are one of the two jawless vertebrate groups in Agnatha. The adult’s life is shorter than the larval stage which is known as “ammocoete”. They are either in parasitic forms or non-parasitic forms. Parasitic adults attach to other species, rely on the blood or flesh of the hosts, and non-parasitic adults die after spawning. There is little historical data on lampreys because ammocoetes are filter feeders who are in the sediment, and captures of adults were all by chance. The objectives I achieved in this study were included: 1) Compiled all existing PA historical data (prior to 1990s) of lampreys and created database and distribution maps for each species; 2) Sampled historical sites for native lampreys in 2011 by using backpack designed for ammocoetes, documented changes in lamprey communities at the watershed scale; 3) Conducted substrate sampling at sites where ammocoetes were present, analyzed substrate size preferred by ammocoetes; 4) Identified collections to species, compared the current data and historical data to see the presence and absence of native lamprey species and value the changes of distributions. -

Southwestern Pennsylvania Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) Permittees

Southwestern Pennsylvania Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) Permittees ALLEGHENY COUNTY Municipality Stormwater Watershed(s) River Watershed(s) Aleppo Twp. Ohio River Ohio River Avalon Borough Ohio River Ohio River Baldwin Borough Monongahela River Monongahela River Peters Creek Monongahela River Sawmill Run Ohio River Baldwin Township Sawmill Run Ohio River Bellevue Borough Ohio River Ohio River Ben Avon Borough Big Sewickley Creek Ohio River Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Bethel Park Borough Peters Creek Monongahela River Chartiers Creek Ohio River Sawmill Run Ohio River Blawnox Borough Allegheny River Allegheny River Brackenridge Borough Allegheny River Allegheny River Bull Creek Allegheny River Braddock Hills Borough Monongahela River Monongahela River Turtle Creek Monongahela River Bradford Woods Pine Run Allegheny River Borough Connoquenessing Creek Beaver River Big Sewickley Creek Ohio River Brentwood Borough Monongahela River Monongahela River Sawmill Run Ohio River Bridgeville Borough Chartiers Creek Ohio River Carnegie Borough Chartiers Creek Ohio River Castle Shannon Chartiers Creek Ohio River Borough Sawmill Run Ohio River ALLEGHENY COUNTY Municipality Stormwater Watershed(s) River Watershed(s) Cheswick Borough Allegheny River Allegheny River Churchill Borough Turtle Creek Monongahela River Clairton City Monongahela River Monongahela River Peters Creek Monongahela River Collier Township Chartiers Creek Ohio River Robinson Run Ohio River Coraopolis Borough Montour Run Ohio River Ohio River Ohio River Crescent Township -

View the Shenango River Watershed Conservation Plan

The Pennsylvania Rivers Conservation Program Shenango River Watershed Conservation Plan July 2005 Prepared for: Shenango River Watershed Community Prepared by: Western Pennsylvania Conservancy Watershed Assistance Center 246 South Walnut Street Blairsville, PA 15717 This project was financed in part by a grant from the Community Conservation Partnership Program under the administration of the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Recreation and Conservation. Shenango River Watershed Conservation Plan ii Shenango River Watershed Conservation Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Title Page……………………………………………………………………. i Letter from Nick Pinizzotto, Western Pennsylvania Conservancy ii Preface………………………………………………………………………. iii Table of Contents iv List of Tables vii List of Figures ix Acknowledgements xi Acronyms xii Watershed Definition xiv Executive Summary………………………………………………………… ES-1 Project Background ES -1 Purpose ES-1 Planning Process ES-2 Implementation ES-2 Chapter Summaries ES-4 Project Area Characteristics ES-4 Land Resources ES-4 Water Resources ES-5 Biological Resources ES-6 Cultural Resources ES-7 Issues and Concerns ES-8 Management Recommendations ES-8 Project Area Characteristics………………………………………………. 1-1 Project Area 1-1 Location 1-1 Size 1-1 Climate 1-9 Topography 1-9 Major Tributaries 1-11 Air Quality 1-11 Atmospheric Deposition 1-12 Critical Pollutants 1-12 Mercury 1-13 Impacts of Air Pollution 1-14 Socio-economic Profile 1-14 Land-Use Planning and Regulation 1-14 Demographics and Population Patterns 1-18 Infrastructure -

Entire Bulletin

Volume 42 Number 44 Saturday, November 3, 2012 • Harrisburg, PA Pages 6851—6988 Agencies in this issue The Governor The Courts Department of Banking and Securities Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Department of Drug and Alcohol Programs Department of Environmental Protection Department of Health Department of Transportation Game Commission Governor’s Advisory Commission on Postsecondary Education Independent Regulatory Review Commission Insurance Department Liquor Control Board Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission Philadelphia Parking Authority State Board of Cosmetology State Board of Nursing State Board of Vehicle Manufacturers, Dealers and Salespersons State Board of Veterinary Medicine State Conservation Commission State Real Estate Commission Susquehanna River Basin Commission Detailed list of contents appears inside. Latest Pennsylvania Code Reporters (Master Transmittal Sheets): No. 456, November 2012 published weekly by Fry Communications, Inc. for the PENNSYLVANIA Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Legislative Reference Bu- BULLETIN reau, 641 Main Capitol Building, Harrisburg, Pa. 17120, (ISSN 0162-2137) under the policy supervision and direction of the Joint Committee on Documents pursuant to Part II of Title 45 of the Pennsylvania Consolidated Statutes (relating to publi- cation and effectiveness of Commonwealth Documents). Subscription rate $82.00 per year, postpaid to points in the United States. Individual copies $2.50. Checks for subscrip- tions and individual copies should be made payable to ‘‘Fry Communications, Inc.’’ Periodicals postage paid at Harris- burg, Pennsylvania. Postmaster send address changes to: Orders for subscriptions and other circulation matters FRY COMMUNICATIONS should be sent to: Attn: Pennsylvania Bulletin 800 W. Church Rd. Fry Communications, Inc. Attn: Pennsylvania Bulletin Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania 17055-3198 800 W. Church Rd. -

Left Logstown, Near the Present Site of An> Bridge, Pennsylvania, On

FROM LOGSTOWN TO VENANGO WITH GEORGE WASHINGTON1 W. WALTER BRAHAM Washington left Logstown, near the present site of An> Georgebridge, Pennsylvania, on Saturday, November 30, 1753, and arrived at Venango, now Franklin, Pennsylvania, on Tuesday, Decem- ber 4. His route between these two points has been the subject of much speculation. Washington's biographers, from John Marshall, who blandly assumes that he went up the Allegheny River, to the late Doug- las Southall Freeman, who traced his route through Branchton inButler County, all adopt without comment the theory of a journey by a direct route from Logstown to Venango by way of Murderingtown. Dr. Free- man's recent and excellent volumes on "Young Washington'' give present point to the inquiry. The first-hand evidence on the trip of Washington to Fort Le Boeuf is of course in the diaries of Washington and of his companion, Christopher Gist, and the map of western Pennsylvania and Virginia believed to have been prepared by Washington himself and now lodged in the British Museum. 2 The diary entries are brief and may be quoted in full. Washington's diary entries concerning this part of his trip are: [Nov.] 30th. We set out about 9 o-Clock with the Half-King, Jeska- kake, White Thunder, and the Hunter; and travelled on the Road to Venango, where we arrived the 4th of December, without any Thing remarkable happening but a continued Series of bad Weather. [Dec] 4£7i. This is an old Indian Town, situated at the Mouth of French Creek on Ohio; and lies near N. -

Calendar No. 504

Calendar No. 504 109TH CONGRESS REPORT " ! 2d Session SENATE 109–274 ENERGY AND WATER APPROPRIATIONS BILL, 2007 JUNE 29, 2006.—Ordered to be printed Mr. DOMENICI, from the Committee on Appropriations, submitted the following REPORT [To accompany H.R. 5427] The Committee on Appropriations, to which was referred the bill (H.R. 5427) making appropriations for energy and water develop- ment for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2007, and for other purposes, reports the same to the Senate with an amendment, and an amendment to the title, and recommends that the bill as amended do pass. Amount in new budget (obligational) authority, fiscal year 2007 Total of bill as reported to the Senate .................... $31,238,000,000 Amount of 2006 appropriations ............................... 1 37,299,714,000 Amount of 2007 budget estimate ............................ 29,980,227,000 Amount of House allowance .................................... 30,526,000,000 Bill as recommended to Senate compared to— 2006 appropriations .......................................... ¥6,061,714,000 2007 budget estimate ........................................ ∂1,257,773,000 House allowance ................................................ ∂712,000,000 1 Includes Emergency Appropriations of $6,600,473,000. 28–409 PDF CONTENTS Page Purpose ..................................................................................................................... 4 Summary of Estimates and Recommendations ..................................................... 4 Title I: Department -

Calendar No. 130

Calendar No. 130 109TH CONGRESS REPORT " ! 1st Session SENATE 109–84 ENERGY AND WATER APPROPRIATIONS BILL, 2006 JUNE 16, 2005.—Ordered to be printed Mr. DOMENICI, from the Committee on Appropriations, submitted the following REPORT [To accompany H.R. 2419] The Committee on Appropriations, to which was referred the bill (H.R. 2419) making appropriations for energy and water develop- ment for the fiscal year ending September 30, 2006, and for other purposes, reports the same to the Senate with an amendment and recommends that the bill as amended do pass. Amount in new budget (obligational) authority, fiscal year 2006 Total of bill as reported to the Senate .................... $31,245,000,000 Amount of 2005 appropriations ............................... 29,832,280,000 Amount of 2006 budget estimate ............................ 29,746,728,000 Amount of House allowance .................................... 29,746,000,000 Bill as recommended to Senate compared to— 2005 appropriations .......................................... ∂1,412,720,000 2006 budget estimate ........................................ ∂1,498,272,000 House allowance ................................................ ∂1,499,000,000 21–815 PDF CONTENTS Page Purpose ..................................................................................................................... 4 Summary of Estimates and Recommendations ..................................................... 4 Title I—Department of Defense—Civil: Department of the Army: Corps of Engineers—Civil: General Investigations -

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - November 2018

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - November 2018 Length County of Mouth Water Trib To Wild Trout Limits Lower Limit Lat Lower Limit Lon (miles) Adams Birch Run Long Pine Run Reservoir Headwaters dnst to mouth 39.950279 -77.444443 3.82 Adams Hosack Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 39.914780 -77.467522 2.90 Adams Latimore Creek Bermudian Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 40.003613 -77.061386 7.00 Adams Little Marsh Creek Marsh Creek Headwaters dnst to T-315 39.842220 -77.372780 3.80 Adams Marsh Creek Out of State Headwaters dnst to SR0030 39.853802 -77.288300 11.12 Adams Opossum Creek Conewago Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 39.931667 -77.185555 12.10 Adams Stillhouse Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 39.915470 -77.467575 1.28 Allegheny Allegheny River Ohio River Headwater dnst to conf Reed Run 41.751389 -78.107498 21.80 Allegheny Kilbuck Run Ohio River Headwaters to UNT at RM 1.25 40.516388 -80.131668 5.17 Allegheny Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Headwaters dnst to mouth 40.554253 -80.206802 7.91 Armstrong Birch Run Allegheny River Headwaters dnst to mouth 41.033300 -79.619414 1.10 Armstrong Bullock Run North Fork Pine Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 40.879723 -79.441391 1.81 Armstrong Cornplanter Run Buffalo Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 40.754444 -79.671944 1.76 Armstrong Cove Run Sugar Creek Headwaters dnst to mouth 40.987652 -79.634421 2.59 Armstrong Crooked Creek Allegheny River Headwaters to conf Pine Rn 40.722221 -79.102501 8.18 Armstrong Foundry Run Mahoning Creek Lake Headwaters -

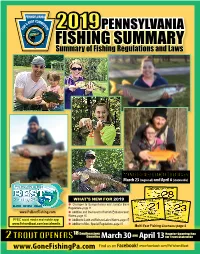

Fishing Summary Fishing Summary

2019PENNSYLVANIA FISHING SUMMARY Summary of Fishing Regulations and Laws MENTORED YOUTH TROUT DAYS March 23 (regional) and April 6 (statewide) WHAT’S NEW FOR 2019 l Changes to Susquehanna and Juniata Bass Regulations–page 11 www.PaBestFishing.com l Addition and Removal to Panfish Enhancement Waters–page 15 PFBC social media and mobile app: l Addition to Catch and Release Lakes Waters–page 15 www.fishandboat.com/socialmedia l Addition to Misc. Special Regulations–page 16 Multi-Year Fishing Licenses–page 5 18 Southeastern Regular Opening Day 2 TROUT OPENERS Counties March 30 AND April 13 for Trout Statewide www.GoneFishingPa.com Go Fishin’ in Franklin County Chambersburg Trout Derby May 4-5, 2019 Area’s #1 Trout Derby ExploreFranklinCountyPA.com Facebook.com/FCVBen | Twitter.com/FCVB 866-646-8060 | 717-552-2977 2 www.fishandboat.com 2019 Pennsylvania Fishing Summary Use the following contacts for answers to your questions or better yet, go onlinePFBC to the PFBC LOCATIONS/TABLE OF CONTENTS website (www.fishandboat.com) for a wealth of information about fishing and boating. FOR MORE INFORMATION: THANK YOU STATE HEADQUARTERS CENTRE REGION OFFICE FISHING LICENSES: for the purchase 1601 Elmerton Avenue 595 East Rolling Ridge Drive Phone: (877) 707-4085 of your fishing P.O. Box 67000 Bellefonte, PA 16823 Harrisburg, PA 17106-7000 Phone: (814) 359-5110 BOAT REGISTRATION/TITLING: Phone: (866) 262-8734 license! Phone: (717) 705-7800 Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. The mission of the Pennsylvania Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. Monday through Friday PUBLICATIONS: Fish & Boat Commission is to Monday through Friday BOATING SAFETY Phone: (717) 705-7835 protect, conserve, and enhance the PFBC WEBSITE: EDUCATION COURSES Commonwealth’s aquatic resources, www.fishandboat.com Phone: (888) 723-4741 and provide fishing and boating www.fishandboat.com/socialmedia opportunities. -

Fishes May Compete for Food Resources; Exotic Mussels May Impact Soft Substrate and Vegetation Growth

2 0 1 5 – 2 0 2 5 Species of Greatest Conservation Need Species Accounts Appendix 1.4E-Fish Fish Species of Greatest Conservation Need Maps: Physiographic Provinces and HUC Watersheds Species Accounts (Click species name below or bookmark to navigate to species account) FISH Ohio Lamprey Tonguetied Minnow Tadpole Madtom Northern Brook Lamprey Cutlip Minnow Margined Madtom Mountain Brook Lamprey Bigmouth Shiner Brindled Madtom Least Brook Lamprey Redfin Shiner Northern Madtom Shortnose Sturgeon Allegheny Pearl Dace Cisco Lake Sturgeon Hornyhead Chub Brook Trout Atlantic Sturgeon Comely Shiner Central Mudminnow Paddlefish Bridle Shiner Eastern Mudminnow Spotted Gar River Shiner Burbot Bowfin Ghost Shiner Allegheny Burbot American Eel Ironcolor Shiner Brook Stickleback Blueback Herring Blackchin Shiner Threespine Stickleback Hickory Shad Swallowtail Shiner Checkered Sculpin Alewife Longnose Sucker Banded Sunfish American Shad Bigmouth Buffalo Warmouth Northern Redbelly Dace Spotted Sucker Longear Sunfish Southern Redbelly Dace White Catfish Eastern Sand Darter Redside Dace Black Bullhead Iowa Darter Streamline Chub Blue Catfish Spotted Darter Gravel Chub Mountain Madtom Tessellated Darter FISH, CONTINUED Tippecanoe Darter Chesapeake Logperch Shield Darter Variegate Darter Longhead Darter The following Physiographic Province and HUC Watershed maps are presented here for reference with conservation actions identified in the species accounts. Species account authors identified appropriate Physiographic Provinces or HUC Watershed (Level 4, 6, 8, 10, or statewide) for specific conservation actions to address identified threats. HUC watersheds used in this document were developed from the Watershed Boundary Dataset, a joint project of the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture-Natural Resources Conservation Service, the U.S. Geological Survey, and the Environmental Protection Agency.