Landscape Character Assessment 2015.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020-Polling-Scheme

SOUTH DUBLIN COUNTY COUNCIL COMHAIRLE CONTAE ÁTHA CLIATH THEAS POLLING SCHEME 2020 SCHEME OF POLLING DISTRICTS AND POLLING PLACES Local Electoral Area Boundary Committee No. 2 Report 2018 1 Scheme of Polling Districts and Polling Places 2020 This polling scheme applies to Dail, Presidential,European Parliament, Local Elections and Referendums. The scheme is made pursuant to Section 18, of the Electoral Act, 1991 as amended by Section 2 of the Electoral (Amendment) Act, 1996, and Sections 12 and 13 of the Electoral (Amendment) Act, 2001 and in accordance with the Electoral ( Polling Schemes) Regulations, 1005. (S.I. No. 108 of 2005 ). These Regulations were made by the Minister of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government under Section 28 (l) of the Electoral Act, 1992. Constituencies are as contained and described in the Constituency Commission Report 2017. Local Electoral Areas are as contained and described in the Local Electoral Area Boundary Committee No. 2 Report 2018 Electoral Divisions are as contained and described in the County Borough of Dublin (Wards) Regulations, 1986 ( S.I.No. 12 of 1986 ), as amended by the County Borough of Dublin (Wards) (Amendment) Regulations, 1994 ( S.I.No. 109 of 1994) and as amended by the County Borough of Dublin (Wards) (Amendment) Regulations 1997 ( S.I.No. 43 of 1997 ). Effective from 15th February 2020 2 Constituencies are as contained and described in the Constituency Commission Report 2017. 3 INDEX DÁIL CONSTITUENCY AREA: LOCAL ELECTORAL AREA: Dublin Mid-West Clondalkin Dublin Mid-West Lucan Dublin Mid- West Palmerstown- Fonthill Dublin South Central Rathfarnham -Templeogue Dublin South West Rathfarnham – Templeogue Dublin South West Firhouse – Bohernabreena Dublin South West Tallaght- Central Dublin South West Tallaght- South 4 POLLING SCHEME 2020 DÁIL CONSTITUENCY AREA: DUBLIN-MID WEST LOCAL ELECTORAL AREA: CLONDALKIN POLLING Book AREA CONTAINED IN POLLING DISTRICT POLLING DISTRICT / ELECTORAL DIVISIONS OF: PLACE Bawnogue 1 FR Clondalkin-Dunawley E.D. -

The Official Voice for the Communities of South Dublin County

The official voice for the Adamstown Clondalkincommunities Jobstown Lucan Newcastle Palmerstownof Rathcoole Rathfarnham Saggart Tallaght Templeogue Adamstown Clondalkin Jobstown Lucan Newcastle PalmerstownSouth Rathcoole Dublin Rathfarnham Saggart Tallaght Templeogue AdamstownCounty. Clondalkin Jobstown Lucan Newcastle Palmerstown Rathcoole Rathfarnham Saggart Tallaght Templeogue Adamstown Clondalkin Jobstown Lucan Newcastle Palmerstown Rathcoole Rathfarnham Saggart Tallaght Templeogue Adamstown Clondalkin Jobstown Lucan Newcastle Palmerstown Rathcoole Rathfarnham Saggart Tallaght Templeogue Lucan Newcastle Adamstown Clondalkin Jobstown Lucan Newcastle Palmerstown Rathcoole Rathfarnham Saggart Tallaght Templeogue Adamstown Clondalkin Jobstown Lucan Newcastle Palmerstown Rathcoole Rathfarnham Saggart Tallaght Templeogue Adamstown Clondalkin Jobstown Lucan Newcastle Palmerstown Rathcoole Rathfarnham Saggart Tallaght Templeogue Adamstown Clondalkin Jobstown Lucan Newcastle Palmerstown Rathcoole Rathfarnham Saggart Tallaght Templeogue Adamstown Clondalkin Jobstown Lucan Newcastle Palmerstown Rathcoole Rathfarnham Saggart Tallaght Templeogue Lucan Newcastle Adamstown Clondalkin Jobstown Lucan Newcastle Palmerstown Rathcoole Rathfarnham Saggart Tallaght Templeogue Adamstown Clondalkin Jobstown Lucan Newcastle Palmerstown Rathcoole Rathfarnham Saggart Tallaght Templeogue Adamstown Clondalkin Jobstown Lucan Newcastle Palmerstown Rathcoole Rathfarnham What is the South Dublin County Public Participation Network? The South Dublin County Public -

Knocklyon News Mar 2020

E - m a i l u s a t k n o c k l y o n n e w s @ g m a i l . c o m M a r c h 2 0 2 0 T o n i g h t b e f o r e f a l l i n g a s l e e p t h i n k a b o u t w h e n w e w i l l r e t u r n t o t h e s t r e e t . W h e n w e h u g a g a i n , w h e n a l l t h e s h o p p i n g t o g e t h e r w i l l s e e m l i k e a p a r t y . L e t ''s t h i n k a b o u t w h e n t h e c o f f e e s w i l l r e t u r n t o t h e b a r , t h e s m a l l t a l k , t h e p h o t o s c l o s e t o e a c h o t h e r . W e t h i n k a b o u t w h e n i t w i l l b e a l l a m e m o r y b u t n o r m a l c y w i l l s e e m a n u n e x p e c t e d a n d b e a u t i f u l g i f t . -

Whitechurch Stream Flood Alleviation Scheme

WHITECHURCH STREAM FLOOD ALLEVIATION SCHEME Environmental Report MDW0825 Environmental Report F01 06 Jul. 20 rpsgroup.com WHITECHURCH STREAM FAS-ER Document status Version Purpose of document Authored by Reviewed by Approved by Review date A01 For Approval HC PC MD 09/04/20 A02 For Approval HC PC MD 02/06/20 F01 For Issue HC PC MD 06/07/20 Approval for issue Mesfin Desta 6 July 2020 © Copyright RPS Group Limited. All rights reserved. The report has been prepared for the exclusive use of our client and unless otherwise agreed in writing by RPS Group Limited no other party may use, make use of or rely on the contents of this report. The report has been compiled using the resources agreed with the client and in accordance with the scope of work agreed with the client. No liability is accepted by RPS Group Limited for any use of this report, other than the purpose for which it was prepared. RPS Group Limited accepts no responsibility for any documents or information supplied to RPS Group Limited by others and no legal liability arising from the use by others of opinions or data contained in this report. It is expressly stated that no independent verification of any documents or information supplied by others has been made. RPS Group Limited has used reasonable skill, care and diligence in compiling this report and no warranty is provided as to the report’s accuracy. No part of this report may be copied or reproduced, by any means, without the written permission of RPS Group Limited. -

River Dodder Greenway from the Sea to the Mountains

River Dodder Greenway From the Sea to the Mountains Feasibility Study Report January 2013 Client: Consulting Engineer: South Dublin County Council Roughan & O'Donovan Civic Offices Arena House Tallaght Arena Road Dublin 24 Sandyford Dublin 18 Roughan & O'Donovan - AECOM Alliance River Dodder Greenway Consulting Engineers Feasibility Study Report River Dodder Greenway From the Sea to the Mountains Feasibility Study Report Document No: ............. 12.176.10 FSR Made: ........................... Eoin O Catháin (EOC) Checked: ...................... Seamus MacGearailt (SMG) Approved: .................... Revision Description Made Checked Approved Date Feasibility Study Report DRAFT EOC SMG November 2012 A (Implementation and Costs included) DRAFT 2 EOC SMG January 2013 B Issue 1 EOC SMG SMG January 2013 Ref: 12.176.10FSR January 2013 Page i Roughan & O'Donovan - AECOM Alliance River Dodder Greenway Consulting Engineers Feasibility Study Report River Dodder Greenway From the Sea to the Mountains Feasibility Study Report TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Background / Planning Context ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

12 Slade Castle Wood Saggart Co. Dublin for SALE

FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY 12 Slade castle Wood Saggart Co. Dublin Three Bedroom Townhouse c.134.sq.m. /1,450sq.ft. Price: €295,000 raycooke.ie DESCRIPTION RAY COOKE AUCTIONEERS are delighted to present this absolutely stunning three bedroom townhouse to the market in the exclusive “Slade FEATURES Castle” development ideally located in the heart of Saggart Village. The location is next to none - ABSOLUTELY STUNNING PROPERTY as within arms reach you will find the N7, M50 - BER C2 Motorway and The Luas Stop. Within walking distance you have local shops, shopping centres, - Immaculate condition throughout schools, bars and restaurants. - c. 1,450 sq ft Interior living accommodation is spread over three - Split over three levels floors and spans to c. 1,450 sq ft, comprising of - - Gas fired central heating entrance hallway, guest wc, kitchen, EXTENDED - Double glazed windows lounge/dining area, all on ground level. The first floor offers two double bedrooms with one - Alarmed ensuite and main family bathroom. The upper - Fully fitted modern kitchen level boasts an extra large master bedroom with another ensuite bathroom. No. 12 is presented - Main bathroom and 2 large ensuites in showhouse condition throughout and could - Three double bedrooms very easily pass as a brand new property. The list - Additional rear extension of additional features is endless and includes gas fired central heating, double glazing throughout, a - Management fees TBC fully fitted modern kitchen, two additional ensuite - Within easy reach of M50 & N7 bathrooms and a large rear extension. - Located in the heart of Saggart Village Viewing of this magnificent property is highly - Every conceivable amenity within walking advised to appreciate its sheer quality, do not miss distance this one! Call Ray Cooke Auctioneers today.. -

Youth and Sport Development Services

Youth and Sport Development Services Socio-economic profile of area and an analysis of current provision 2018 A socio economic analysis of the six areas serviced by the DDLETB Youth Service and a detailed breakdown of the current provision. Contents Section 3: Socio-demographic Profile OVERVIEW ........................................................................................................... 7 General Health ........................................................................................................................................................... 10 Crime ......................................................................................................................................................................... 24 Deprivation Index ...................................................................................................................................................... 33 Educational attainment/Profile ................................................................................................................................. 38 Key findings from Socio Demographic Profile ........................................................................................................... 42 Socio-demographic Profile DDLETB by Areas an Overview ........................................................................................... 44 Demographic profile of young people ....................................................................................................................... 44 Pobal -

The Parishes of Mary Immaculate; St Michael's, Inchicore and Our Lady

The Parishes of Mary Immaculate; St Michael’s, Inchicore and Our Lady of the Wayside, Bluebell. Oblate Pastoral Area Newsletter Tenth Sunday in Ordinary Time 10th June 2018 The Blessed Sacrament The Pastoral Area Masses & Confessions On Sunday 3rd May 2018 we celebrated Mary Immaculate the wonderful Feast of Corpus Christi or the Body of Christ. This feast was Sundays: (Vigil) Sat 7pm, introduced by the Church to help us to 8am, 11am, 7pm reflect on and to thank Christ for this Weekdays Mon – Fri 7am great gift. The Eucharist was instituted 10am, 7pm, Sat 11am by Jesus Christ during the Last Supper Holy Days 7pm (Vigil), 7am, when He gathered with His disciples the 10am, 7pm night before He died on Calvary. During Holy Days that fall on a Saturday this meal Jesus prayed for His disciples (and us) and stressed the importance of 7pm (Vigil), 11am, 7pm them being united and supportive of Confessions Sat 10.30 - 11am & each other. He gave us the Eucharist as 6.30 - 7pm a sign of our unity with Him and with each other. However the Eucharist must St Michael’s never be seen as just a relationship between Jesus and me. It binds us into the Sundays (Vigil) Sat 6.30pm community of disciples as St Paul tells us in his letter to the 1 Corinthians Sunday 9am & 11am (Family) 10:17 “ …. we are one body, for we all share the one bread.” It is meant to Weekdays (Mon – Fri) 10am strengthen us for the journey of life and to enable us to give witness to Him by Liturgy of the Word & Communion on our daily living and active concern for others. -

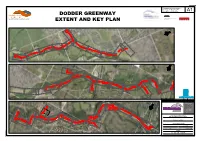

Fa-File-Pdf 13 102 00 2200 A.Pdf 15.51 MB

This drawing is produced using the Irish Transverse Mercator (ITM) Geographic Coordinate System A1 Comhairle Contae DODDER GREENWAY LEGEND: ÈWKD&OLDWK7KHDV PROPOSED SCHEME EXTENT South Dublin County Council EXTENT AND KEY PLAN KEY PLAN DWG No. 2203 LAYOUT - 6 DALEPARK ROAD FIRHOUSE ROAD WEST ELLENSBOROUGH LAYOUT - 7 LAYOUT - 5 LAYOUT - 4 LAYOUT - 8 DWG No. 2204 DWG No. 2203 LAYOUT - 3 LAYOUT - 11 KILTIPPER ROAD DWG No. 2202 LAYOUT - 9 LAYOUT - 10 LAYOUT - 2 DWG No. 2204 LAYOUT - 1 DWG No. 2206 DWG No. 2202 OLDBAWN ROAD RIVER DODDER RIVER DODDER DWG No. 2205 DWG No. 2205 DWG No. 2201 DWG No. 2201 FRIARSTOWN UPPER BOHERNABREENA ROAD LAYOUT - 19 DWG No. 2210 LAYOUT - 20 DWG No. 2210 LAYOUT - 22 LAYOUT - 27 LAYOUT - 18 DWG No. 2209 LAYOUT - 17 LAYOUT - 23 LAYOUT - 25 M50 AVONMORE ROAD RIVER DODDER DWG No. 2213 LAYOUT - 15 DODDER LINEAR PARK DWG No. 2214 DWG No. 2208 LAYOUT - 26 OLD BRIDGE ROAD DWG No. 2211 LAYOUT - 24 LAYOUT - 12 RIVER DODDER WELLINGTON LANE DWG No. 2211 No. DWG DWG No. 2209 21 - LAYOUT LAYOUT - 28 DWG No. 2212 LAYOUT - 13 LAYOUT - 14 DWG No. 2213 FIRHOUSE ROAD DWG No. 2212 DWG No. 2206 DWG No. 2214 DWG No. 2207 DWG No. 2207 LAYOUT - 16 DWG No. 2208 PARK WOODBROOK BALLYROAN ROAD BALLYCULLEN ROAD A KEY PLAN ADDED, TITLE BLOCK AMENDED KT 06/04/17 Revision Description Initials Date Clifton Scannell Emerson LAYOUT - 40 Associates Limited Consulting Engineers, LAYOUT - 41 Seafort Lodge, Castledawson Avenue, Blackrock, Co. Dublin, LAYOUT - 39 Ireland. DWG No. 2220 40 LAYOUT - 33 T. -

This Includes Dublin North Central

CHO 9 - Service Provider Resumption of Adult Day Services Portal For further information please contact your service provider directly. Last updated 2/03/21 Service Provider Organisation Location Id Day Service Location Name Address Area Telephone Number Email Address AUTISM INITIATIVES IRELAND 2760 AUTISM INITATIVES BOTANIC HORIZONS 202 Botanic Ave, Glasnevin, Dublin 9 Do9y861 DUBLIN NORTH CENTRAL 0831068092 [email protected] CENTRAL REMEDIAL CLINIC 2951 CRC - FIRHOUSE Firhouse Shopping Centre, Firhouse, Dublin 24 D24ty24 DUBLIN NORTH CENTRAL 01-4621826 [email protected] CENTRAL REMEDIAL CLINIC 3859 CRC CLONTARF LOCAL CENTRE Penny Ansley Memorial Building, Vernon Avenue, Clontarf Dublin 3 DUBLIN NORTH CENTRAL 8542290 [email protected] CENTRAL REMEDIAL CLINIC 3239 CRC COOLOCK LOCAL CENTRE Clontarf, Dublin 3, DUBLIN NORTH CENTRAL 854 2241 [email protected] CENTRAL REMEDIAL CLINIC 2928 CRC HARTSTOWN LOCAL CENTRE Hartstown Local Centre, Hartstown, Blanchardstown Dublin 15 D15t66c NORTH WEST DUBLIN 087-3690502 [email protected] CENTRAL REMEDIAL CLINIC 56 CRC RT PROGRAMME Vernon Avenue, Clontarf, Dublin 3 DUBLIN NORTH CENTRAL 01-8542396 [email protected] CENTRAL REMEDIAL CLINIC 383 CRC-TRAINING & DEV CENTRE Vernon Avenue, Clontarf, Dublin 3 D03r973 DUBLIN NORTH CENTRAL 01-8542335 [email protected] CHILD VISION 2388 CHILD VISION Grace Park Road, Drumcondra, Dublin 9 D09wkoh DUBLIN NORTH CENTRAL 01 8373635 [email protected] DAUGHTERS OF CHARITY SERVICES 2789 DOC - GLENHILL HOUSE Glenhill House, Finglas, Dublin 11 -D11r85e NORTH WEST DUBLIN 087- 1961476 [email protected] DAUGHTERS OF CHARITY SERVICES 2791 DOC - PARNELL COMMUNITY PROGRAMME 40 Parnell Drive, Parnell Estate, Dublin 15 NORTH WEST DUBLIN 087 196 1476 [email protected] DAUGHTERS OF CHARITY SERVICES 2920 DOC - ST. -

Templeogue/Walkinstown/Rathfarnham/Firhouse

Population Growth & Housing 27,596 28% total of outh Dulins ational and egional planning 28% households housing stock policy emphasises compact of outh (98,387) growth in the Dublin Metropolitan Dulins Area, particularly within the M50 Population in the case of this neighourhood 78,244 living in this all lands to the east. The ational 91% neighourhood Planning ramework emphasises bungalows/ the importance of placemaking houses through the development of 183 lder than 9% fats ounty average attractive places supported y oneoff apartments Population eisting and planned transport houses 19% infrastructure now and into the 15% renters future. The challenge for this plan Healthy 59% in facilitating increased Population 3% rent free 22% TEMPLEOGUE/WALKINSTOWN/RATHFARNHAM/FIRHOUSE population and housing in this 90% not stated area will e to identify appropriate are in very good nfed nd inf deeent High Home good health opportunities which protect Ownership 1% Q What are the Issues and Opportunities in YOUR Area? existing amenities, underpin 82% are are in advery eisting physical and community homeowners ad health infrastructure and epand this Q How might compact growth affect you? where necessary. Introduction & Context includes bus transportation links to development potential in this Community Services The Development Plan presents an Built Environment & Dulin ity entre and to Tallaght to neighourhood. s these areas opportunity to assess the provision Place Making The Templeogue alkinstown the west. develop, it is vital that they do so ustainale neighourhoods are of services in this area and to plan athfarnham irhouse with the necessary supporting supported y a range of for future needs in a strategic and ey to providing great places in neighourhood is located km trong neighourhoods eist in this facilities and services to facilitate the community facilities that are ft for evidenced ased manner. -

For Sale Saggart, Co

1, 2 & 3 GARTERS LANE, FOR SAGGART, CO. DUBLIN SALE PRIVATE GATED DEVELOPMENT INCORPORATING 3 LARGE FAMILY BY PRIVATE TREATY HOMES AND AN ADDITIONAL SITE EXTENDING TO APPROX. 0.3 ACRES CITYWEST HOTEL & GOLF CLUB SAGGART ROAD CITYWEST HOTEL ENTRANCE For illustrative purposes only. GATED DEVELOPMENT SWORDS MALAHIDE M1 N2 DUNBOYNE M3 DUBLIN AIRPORT 1, 2 & 3 GARTERS LANE, PORTMARNOCK FOR SALE SAGGART, CO. DUBLIN M50 BY PRIVATE TREATY SANTRY PRIVATE GATED DEVELOPMENT INCORPORATING 3 LARGE FAMILY M1 HOMES AND AN ADDITIONAL SITE EXTENDING TO APPROX. 0.3 ACRES M3 M50 BEAUMONT BLANCHARDSTOWN TRAIN LINE N1 EXPRESS PORT TUNNEL DRUMCONDRA LOCATION CLONTARF N4 PHOENIX LUCAN PARK DUBLIN PORT The offering is prominently positioned on Garters Lane, on the M50 DUBLIN outskirts of Saggart Village, adjacent to the popular City West Hotel CITY CENTRE DUBLIN and Golf Club. BAY Saggart has being recognised as Ireland’s fastest growing town in LUAS RED LINE BALLSBRIDGE census 2016, it also earned the title in the preceding 2011 census. CLONDALKIN CRUMLIN Located approx. 18 km from Dublin City Centre the town offers the advantages of being closely located to the Ireland’s capital city yet M50 N7 LUAS GREEN LINE presents a tranquil setting on the edge of the Dublin Mountains. RATHFARNHAM N31 Retail facilities are growing along with the population in the area. GARTERS N11 BLACKROCK DUN LAOGHAIRE Citywest Village Shopping Centre is situated 1.3km from the LANE TALLAGHT DUNDRUM properties. The village of Saggart offers Dunnes Stores and Insomnia N7 N81 along with a host of eateries and pubs. Award winning store, Avoca, SANDYFORD MARLEY IND.