Nebraska Tractor Shows, 1913-1919, and the Beginning of Power Farming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creating Farm Foundation 47 Chapter 4: Hiring Henry C

© 2007 by Farm Foundation This book was published by Farm Foundation for nonprofit educational purposes. Farm Foundation is a non-profit organization working to improve the economic and social well being of U.S. agriculture, the food system and rural communities by serving as a catalyst to assist private- and public-sector decision makers in identifying and understanding forces that will shape the future. ISBN: 978-0-615-17375-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2007940452 Cover design by Howard Vitek Page design by Patricia Frey No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher: Farm Foundation 1301 West 22nd Street, Suite 615 Oak Brook, Illinois 60523 Web site: www.farmfoundation.org First edition. Published 2007 Table of Contents R.J. Hildreth – A Tribute v Prologue vii Chapter 1: Legge and Lowden 1 Chapter 2: Events Leading to the Founding of Farm Foundation 29 Chapter 3: Creating Farm Foundation 47 Chapter 4: Hiring Henry C. Taylor 63 Chapter 5: The Taylor Years 69 Chapter 6: The Birth and Growth of Committees 89 Chapter 7: National Public Policy Education Committee 107 Chapter 8: Farm Foundation Programming in the 1950s and 1960s 133 Chapter 9: Farm Foundation Round Table 141 Chapter 10: The Hildreth Legacy: Farm Foundation Programming in the 1970s and 1980s 153 Chapter 11: The Armbruster Era: Strategic Planning and Programming 1991-2007 169 Chapter 12: Farm Foundation’s Financial History 181 Chapter 13: The Future 197 Acknowledgments 205 Endnotes 207 Appendix 223 About the Authors 237 R.J. -

War Collectivism in World War I

WAR COLLECTIVISM Power, Business, and the Intellectual Class in World War I WAR COLLECTIVISM Power, Business, and the Intellectual Class in World War I Murray N. Rothbard MISES INSTITUTE AUBURN, ALABAMA Cover photo copyright © Imperial War Museum. Photograph by Nicholls Horace of “Munition workers in a shell warehouse at National Shell Filling Factory No.6, Chilwell, Nottinghamshire in 1917.” Copyright © 2012 by the Ludwig von Mises Institute. Permission to reprint in whole or in part is gladly granted, provided full credit is given. Ludwig von Mises Institute 518 West Magnolia Avenue Auburn, Alabama 36832 mises.org ISBN: 978-1-61016-250-0 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. War Collectivism in World War I . .7 II. World War I as Fulfillment: Power and the Intellectuals. .53 Introduction . .53 Piestism and Prohibition . .57 Women at War and at the Polls . .66 Savings Our Boys from Alcohol and Vice . .74 The New Republic Collectivists. .83 Economics in Service of the State: The Empiricism of Richard T. Ely. .94 Economics in Service of the State: Government and Statistics . .104 Index . .127 5 I War Collectivism in World War I ore than any other single period, World War I was the Mcritical watershed for the American business system. It was a “war collectivism,” a totally planned economy run largely by big-business interests through the instrumentality of the cen- tral government, which served as the model, the precedent, and the inspiration for state corporate capitalism for the remainder of the twentieth century. That inspiration and precedent emerged not only in the United States, but also in the war economies of the major com- batants of World War I. -

Producing a Past: Cyrus Mccormick's Reaper from Heritage to History

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2014 Producing a Past: Cyrus Mccormick's Reaper from Heritage to History Daniel Peter Ott Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Ott, Daniel Peter, "Producing a Past: Cyrus Mccormick's Reaper from Heritage to History" (2014). Dissertations. 1486. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1486 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2014 Daniel Peter Ott LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO PRODUCING A PAST: CYRUS MCCORMICK’S REAPER FROM HERITAGE TO HISTORY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY JOINT PROGRAM IN AMERICAN HISTORY / PUBLIC HISTORY BY DANIEL PETER OTT CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MAY 2015 Copyright by Daniel Ott, 2015 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation is the result of four years of work as a graduate student at Loyola University Chicago, but is the scholarly culmination of my love of history which began more than a decade before I moved to Chicago. At no point was I ever alone on this journey, always inspired and supported by a large cast of teachers, professors, colleagues, co-workers, friends and family. I am indebted to them all for making this dissertation possible, and for supporting my personal and scholarly growth. -

SUBJECT FILES, 1933-1964 153 Linear Feet, 2 Linear Inches (350 LGA-S Boxes) Herbert Hoover Presidential Library

Stanford HERBERT HOOVER PAPERS POST PRESIDENTIAL SUBJECT FILES, 1933-1964 153 linear feet, 2 linear inches (350 LGA-S boxes) Herbert Hoover Presidential Library FOLDER LIST Box Contents 1 A General (5 folders) Academy of American Poets, 1934-1959 Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences, Hoover tribute to Ethel Barrymore, 1949 Acheson, Secretary of State Dean - Clippings, 1945-1951 Adams, John – letter to his son, Dec 17, 1800 (reproduction) Advertising Club of New York, 1939-1963 Advertising Council, 1961 Advertising Gold Medal Award of Printers' Ink Publishing Company, 1960-1963 Africa, 1957-1963 African-American Institute, 1958 2 Agricultural Hall of Fame, 1959 Agriculture General, 1934-1953 California Farm Debt Adjustment Committee, 1934-1935 Clippings, 1933-1936 (7 folders) 3 Clippings, 1936-1958, undated (7 folders) Comments and Suggestions, 1933-1935 (3 folders) 4 Comments and Suggestions, 1936-1951, undated (5 folders) Congressional Record, House and Senate Bills, 1917, 1933-1937, 1942-1943 Commodities Cotton, 1934-1943 Wheat, 1933-1943 Farmers' Independence Council of America, 1935-1936 International, 1933-1934 5 Printed Matter, 1934-1953 and undated (2 folders) Statistics, 1940-1944 Agriculture Department Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) Expenditures for 1935 by state, 1936 Printed Material 1933-1941 (2 folders) Bureau of Agricultural Economics Agricultural Finance Review, 1942-1944 6 Agricultural Prices, 1943-1945 (3 folders) Agricultural Situation, 1943-1946 Cotton Situation, 1943 Crop Production, 1942-1946 (4 -

2013-Carlisle-Ford-Nationals

OFFICIAL EVENT DIRECTORY OFFICIAL DIRECTORY PARTNER VISIT BUILDING T FOR YOUR EVENT SHIRTS AT THE CARLISLE STORE WELCOME KEN APPELL, EVENT MANAGER 1970 GRABBER ORANGE BOSS 302 — IT COMMANDS ATTENTION ’d like to personally welcome you to the 2013 edition elcome to the largest all-Ford event in the world. Iof the Carlisle Ford Nationals and want to thank each WFrom show-quality F-150s to Shelby GT350s, and every one of you for supporting us this year and from parts at the swap meet to complete cars for sale for many returning attendees. Like many of you here in the car corral, it’s all here this weekend. this weekend I’ve attended this event almost every year While the cars here represent a broad spectrum of since the early 2000s. I am particularly honored to be interests, including Lincoln/Mercury and European able to step into the role of Event Manager at a time Ford alongside First-gen Mustangs and F-series that the car market is ever-changing. trucks, everyone here shares the same passion for the Th roughout the weekend, I hope you take the time brand. And if you look back, I’m willing to bet you to to visit the unique displays and celebrations. First, can pinpoint the moment that sparked that passion for take a look at the 50th Anniversary of the HiPo 289 in you. Building G. Th ere are some really unique Mustangs, For me, that moment was in 2001, when a Grabber Fairlanes and a few other HiPo 289-powered vehicles Orange ’70 Boss 302 came into the small auto that are a real treat to see, including Milo Coleman’s repair shop where I worked. -

To View Or Download a List of Available Manuals, Please Click Here

Branch 15 Library Items For Checkout Item MfgName Year Pages Document Type 56 Army & Air Force crane shovel 1955 329 User & Maintenance Original 19 Belting, Notes & Rules 1913 3 User & Maintenance Computer Printout 16 P10 Pump - Pressure Tank 4 Sales Information Original 1 Advance-Rumely Universal Steam Engine 15 Sales Information Reprint 11 Allis Chalmers AC letter about buhr stone mill 1927 1 Sales Information Original 5 Allis Chalmers HD14 32 User & Maintenance Original 6 Allis Chalmers HD14 103 Parts Listing Original 7 Allis Chalmers HD7 62 User & Maintenance Original 3 Allis Chalmers HD7 1948 128 Parts Listing Original 162 Allis Chalmers Model C - Instruction/Parts 78 User & Maintenance Original 12 Allis Chalmers Nordyke & Marmon catalog 1927 23 Sales Information Original 9 American Bosch Fuel Injection Equipment 1952 49 User & Maintenance Original 8 Anderson Oil Engines Sales brouchure 26 Sales Information Reprint 10 Arcade Flour Mill No. 9084 2 User & Maintenance Original 4 Auction Flyer Pat Gallagher estate auction 1988 12 Sales Information Photo Copy 146 Aultman & Taylor Tractors, Machinery, and Steam 1922 64 Sales Information Reprint 145 Avery Company Avery tractor manual 1920 110 User & Maintenance Original 149 Avery Company Tractors, Trucks, Motor Cultivators, Threshers, 1922 96 Sales Information Reprint Plows, etc. 5/24/2021 Page 1 of 10 Item MfgName Year Pages Document Type 17 Bay City Shovels Model 30 shovel 1949 60+ User & Maintenance Original 14 Briggs & Stratton 18" lawn mower 1950? 4 User & Maintenance Original 152 Briggs & Stratton Illustrated Parts List Model "U" - "UR" 4 Parts Listing Photo Copy 13 Briggs & Stratton Model 5S Engine 1950? 30 User & Maintenance Original 20 Brown-Cochran Gas Engine Catalog 31 Sales Information Photo Copy 21 Bullseye (Montgomery Ward) Engine Stripping 1 Miscellaneous paper Photo Copy 18 Byers Model 61-71 shovel 60+ User & Maintenance Original 28 C. -

National 4-H Congress Chicago, Illinois

National 4-H Congress in Chicago DRAFT COPY – November 2017 National 4-H Congress Chicago, Illinois 4-H Congress in Chicago DRAFT COPY Page 1 of 178 November 2017 National 4-H Congress in Chicago DRAFT COPY – November 2017 Table of Contents Introduction 5 In the Beginning 6 First Annual Club Tour 7 1920 Junior Club Tour 9 Let =s Start a Committee 12 The 1921 Junior Club Tour 13 Rally at the 'Y' 16 Visit to the Packing Plants 17 Swift & Company 17 Morris & Company 18 The Wilson Banquet 18 Mr. Wilson's Address 19 Wednesday BLoop Day 20 National 4-H Club Congress - The 1920s 20 1922 20 1923 22 1924 23 1925 24 1926 27 1927 29 1928 31 1929 34 National 4-H Club Congress - The 1930s 35 1930 35 1931 36 1932 39 1933 43 1934 44 1935 46 1936 46 1937 47 1938 48 1939 49 National 4-H Congress - the 1940s 50 1940 and 1941 51 1942 51 1943 53 1944 54 1945 55 1946 58 1947 60 1948 61 1949 62 National 4-H Congress - the 1950s 62 1950 63 1951 64 1952 67 1953 70 1954 71 1955 74 1956 76 1957 77 1958 78 1959 79 National 4-H Congress - the 1960s 81 1960 81 1961 82 1962 83 1963 85 4-H Congress in Chicago DRAFT COPY Page 2 of 178 November 2017 National 4-H Congress in Chicago DRAFT COPY – November 2017 1964 86 1965 86 1966 88 1967 89 1968 90 1969 92 National 4-H Congress - the 1970s 96 1970 96 1971 98 1972 102 1973 105 1974 107 1975 108 1976 109 1977 110 1978 112 1979 114 National 4-H Congress - The 1980s 115 1980 115 1981 116 1982 119 1983 121 1984 123 1985 124 1986 125 1987 126 1988 127 1989 128 National 4-H Congress - The 1990s 129 1990 129 1991 129 1992 130 1993 130 1994 130 Congress Traditions and Highlights 130 Opening Assembly 130 Sunday Evening Club/Central Church Special 4-H Services 131 Firestone Breakfast 131 National Live Stock Exposition Parade 132 National 4-H Dress Revue 132 National Awards Donor Banquets and Events 132 "Pop" Concert with the Chicago Symphony 134 Auditorium Theater Concerts 135 Congress Tours 136 Thomas E. -

Trade Catalogs in Degolyer Library

TRADE CATALOGS IN DEGOLYER LIBRARY 1. AGRICULTURE. A. Buch's Sons Co. ILLUSTRATED CATALOGUE AND PRICE LIST. LAND ROLLERS, LAWN ROLLERS, CORN SHELLERS, WHEELBARROWS, CORN MARKERS, STRAW AND FEED CUTTERS, STEEL AND CAST TROUGHS FOR STOCK, CELLAR GRATES, AND A FULL LINE OF SMALL IMPLEMENTS. (Elizabethtown PA, 1903). 64pp. 2. AGRICULTURE. A. W. Coates & Co. CENTENNIAL DESCRIPTIVE CIRCULAR OF THE COATES LOCK-LEVER HAY AND GRAIN RAKE. (Alliance OH, 1876). 3. AGRICULTURE. Abeneque Machine Works. GAS & GASOLENE ENGINES. TRACTION ENGINES, WOOD SAWING OUTFITS, PUMPING PLANTS, PNEUMATIC WATER SYSTEMS, HAY PRESSES, HAY HOISTS, GRINDERS, ENSILAGE CUTTERS, SAW MILLS, THRESHING MACHINES, GENERAL FARM MACHINERY. (Westminster Station VT, 1908)., 24pp. 4. AGRICULTURE. Albion Mfg. Co. Gale Sulky Harrow Mfg. Co. GALE SULKY HARROW CULTIVATOR & SEEDER. (Detroit & Albion MI, [1882]). 5. AGRICULTURE. American Harrow Company. AMERICAN. THE MAKING AND SELLING OF AMERICAN MANURE SPREADERS. (Detroit MI, 1907). 6. AGRICULTURE. American Seeding Machine Co. Empire Drill Co. AMERICAN SEEDING MACHINE CO. ALMANAC AND HOUSEHOLD ENCYCLOPEDIA. (Springfield OH, 1905). 7. AGRICULTURE. Avery Company Manufacturers. AVERY TRACTORS, PLOWS, SEPARATORS, AND STEAM ENGINES. (Peoria IL, 1916). 8. AGRICULTURE. Avery Power Machinery Co. AVERY STEEL THRESHERS. BETTER AND SIMPLER. (Peoria IL, circa 1930). 9. AGRICULTURE. B - L - K Milker Company. B - L - K MILKER. (Little Falls NY, circa 1930, 8pp.. 1O. AGRICULTURE. Bateman Bros. Inc. CATALOGUE No. 28. FARM IMPLEMENTS AND SUPPLIES. (Philadelphia PA, 1928); 171pp. 11. AGRICULTURE. Bateman Manufacturing Company. IRON AGE FARM, GARDEN AND ORCHARD IMPLEMENTS. HOME, FARM AND MARKET GARDENING WITH MODERN TOOLS. (Grenloch NJ, 1918). 12. AGRICULTURE. [Bees]. A.I.Root Company. ROOT QUALITY BEE SUPPLIES. -

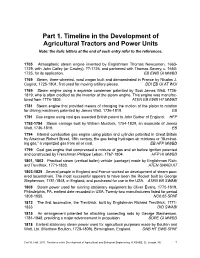

Part 1. Timeline in the Development of Agricultural Tractors and Power Units Note: the Italic Letters at the End of Each Entry Refer to the References

Part 1. Timeline in the Development of Agricultural Tractors and Power Units Note: the italic letters at the end of each entry refer to the references. 1705 Atmospheric steam engine invented by Englishmen Thomas Newcomen, 1663- 1729, with John Calley (or Cawley), ??-1725, and partnered with Thomas Savery, c. 1650- 1725, for its application. EB EWB GI MWBD 1769 Steam, three-wheeled, road wagon built and demonstrated in France by Nicolas J. Cugnot, 1725-1804, first used for moving artillery pieces. DDI EB GI AT WOI 1769 Steam engine using a separate condenser patented by Scot James Watt, 1736- 1819, who is often credited as the inventor of the steam engine. This engine was manufac- tured from 1774-1806. ATEN EB EWB HT MWBD 1781 Steam engine that provided means of changing the motion of the piston to rotation for driving machinery patented by James Watt, 1736-1819. EB 1791 Gas engine using coal gas awarded British patent to John Barber of England. HFP 1792-1794 Steam carriage built by William Murdock, 1754-1839, an associate of James Watt, 1736-1819. EB 1794 Internal combustion gas engine using piston and cylinder patented in Great Britain by American Robert Street, 18th century, the gas being hydrogen-air mixtures or “illuminat- ing gas,” a vaporized gas from oil or coal. EB HFP MWBD 1799 Coal gas engine that compressed a mixture of gas and air before ignition patented and constructed by Frenchman Philippe Lebon, 1767-1804. HFP HI MWBD 1801, 1802 Practical steam (vertical boiler) vehicle (carriage) made by Englishman Rich- ard Trevithick, 1771-1833. -

January 18, 1908

Tiit• financial erct31 I de INCLUDING 8ank and Quotation Section (Monthly) State and City Section(semi-Annuetzi ..aailwav and Industrial section (Quarterly) Street Railway Section (Thre ThEov VOL. 86. SATURDAY, JANUARY 18 1908. NO. 2221. Week ending January 11. Whe Thronicle• Clearings at Inc. or PUBLISHED WEEKLY. • 1908. 1907. • Dec. 1906. 1905. Terms of Subscription-Payable in Advance -v0.0 Boston 144,558,510 Per 206,504,566 187,418,084 152,681,191 One Year $10 00 Providence 7,091,300 9,011,100 -21.3 8,875,300 8,226.000 For Six Months 6 0(1 Hartford 4,400,060 New II 4,824-158 -8.8 3,997.318 3,487.838 European Subscription (including postage) 173 5000 'iv e n _ _ _ _ 3.083,304 2,957 460 +4.3 2,670,369 2,490.538 European Subscription six months (including postage) Springfield 2,004,685 2.114,262 -5.2 2,204,308 1,630,335 Annual Portland 2.123,517 1,985,169 +7.0 Subscription in London (including ft stage) £2 148. Worcester 2,172.627 1,613,772 Six Months Subscription in London (including postage) £1 118. 1,338 060 1,633,952 -18.1 1,623,004 1.490,804 Fall River 999,552 1.172.454 Canadian Subscription (including postage) $11 50 New -14.8 1,030,947 638.512 Bedford_ __.. 743,660 888,727 -16.3 753.408 635,405 Subscription includes following Holyoke 541,674 623,215 Supplements-- Lowell -13.2 460.367 547.359 526,390 577.783 -8.9 663,030 545.643 II INK AND QUOTATION (monthly) STATE AND CITY (semi-annually) Total New Eng 167,410,712 232,292,846 -27.9 RAILWAY AND INDUSTRIAL (quarterly) STREET RAILWAY(3 times yearly) 211,869,162 174,168,197 Chicago -

America's Great Depression

America’s Great Depression Fifth Edition America’s Great Depression Fifth Edition Murray N. Rothbard MISES INSTITUTE Copyright © 1963, 1972 by Murray N. Rothbard Introduction to the Third Edition Copyright © 1975 by Murray N. Rothbard Introduction to the Fourth Edition Copyright © 1983 by Murray N. Rothbard Introduction to the Fifth Edition Copyright © 2000 by The Ludwig von Mises Institute Copyright © 2000 by The Ludwig von Mises Institute All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of reprints in the context of reviews. For information write The Ludwig von Mises Institute, 518 West Magnolia Avenue, Auburn, Alabama 36832. ISBN No.: 0-945466-05-6 TO JOEY, the indispensable framework The Ludwig von Mises Institute dedicates this volume to all of its generous donors, and in particular wishes to thank these Patrons: Dr. Gary G. Schlarbaum – George N. Gallagher (In Memoriam), Mary Jacob, Hugh E. Ledbetter – Mark M. Adamo, Lloyd Alaback, Robert Blumen, Philip G. Brumder, Anthony Deden (Sage Capital Management, Inc.), Mr. and Mrs. Willard Fischer, Larry R. Gies, Mr. and Mrs. W.R. Hogan, Jr., Mr. and Mrs. William W. Massey, Jr., Ellice McDonald, Jr., MBE, Rosa Hayward McDonald, MBE, Richard McInnis, Mr. and Mrs. Roger Milliken (Milliken and Company), James M. Rodney, Sheldon Rose, Mr. and Mrs. Edward Schoppe, Jr., Mr. and Mrs. Robert E. Urie, Dr. Thomas L. Wenck – Algernon Land Co., L.L.C., J. Terry Anderson (Anderson Chemical Company), G. Douglas Collins, Jr., George Crispin, Lee A. -

NEWSLETTER HOWARD COUNTY FARM BUREAU Volume 25, Issue 2 March 2015

NEWSLETTER HOWARD COUNTY FARM BUREAU Volume 25, Issue 2 March 2015 ~Contacts~ The Mulch Task Force has wrapped up their Howie Feaga, President (410) 531-2360 meetings and it will be up to Planning and Zoning ay Rhine, Vice-President (410) 442-2445 to hopefully write the new law, so that it will be Leslie Bauer, Secretary (410) 531-6261 favorable to everyone. The members of the Task Donald Bandel, Treasurer (410) 531-7918 Mandy Ackman, Newsletter Editor (240) 638-6174 Force put a ton of time and energy into working on both safe and economically stable recommendations WEBSITE: www.howardfarmbureau.org that should work for everyone. The Ag people on the task force were Lynn Moore, Cathy Hudson, Kathy Zimmerman, Martha Ann Clark, Brent Message to Members Rutley, Bob Ensor, Bob Orndorff, Keith Ohlinger, Justin Brendel, and the Co-Chair Zack Brendel. I By: Howie Feaga, President Howard County want to thank them for all their time and efforts. Farm Bureau We will all need your help when the time comes to get into law what the Council will be voting on We made it to March; wow did it get cold in when the final bill is written, so that we can once February or what? I can only imagine how bad it again have Composting and small Mulching back was in the upper northeast with 7 feet of snow. into our RR and RC areas as well as in our Ag Hopefully all the farmers and their families did OK Preservation Parcels. Stay tuned and we will do our up there, and are beginning to thaw out and get best to keep you up to date.