Wharfedale and Littondale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Roman Dog from Conistone Dib, Upper Wharfedale, UK, and Its Palaeohydrological Significance

This is a repository copy of A Roman dog from Conistone Dib, Upper Wharfedale, UK, and its palaeohydrological significance.. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/161733/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Murphy, PJ and Chamberlain, AT (2020) A Roman dog from Conistone Dib, Upper Wharfedale, UK, and its palaeohydrological significance. Cave and Karst Science, 47 (1). pp. 39-40. ISSN 1356-191X This article is protected by copyright. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ A Roman dog from Conistone Dibb, Wharfedale, and its palaeohydrological significance Phillip J Murphy1 and Andrew Chamberlain2 1: School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, LS29JT, UK 2: School of Environment, University of Manchester, UK Conistone Dibb is a dry valley on the eastern flank of the glaciated trough of Wharfedale. The dry valley joins Wharfedale at the site of the hamlet of Conistone between Kettllewell and Grassington (Figure 1). -

Grassington and Conistone

THURSDAY, JUNE 18, 2015 The Northern Echo 39 Walks what’son Walks Grassington and Conistone dry valleys and outcrops all around. on, passing some barns on your Walk information From Dib Beck, a track leads down right, to reach two gates at the end to Conistone with superb views of the walled track. Head through Distance: 10.75 km (6.7 miles) towards the impressive bulk of the right-hand gate and walk Time: 3 hours Kilnsey Crag. From Conistone, straight on across the field, through a footpath leads up through the a gateway in a wall then straight on Maps: Ordnance Survey Explorer spectacular dry limestone valley of (bearing very slightly to the right) OL2 - always carry an OS map on Conistone Dib, one of the ‘natural to reach a wall-stile that leads into your walk wonders’ of the Yorkshire Dales. Grass Wood. Parking: Large pay & display This deep steep-sided gorge was car park along Hebden Road at scoured out by glacial meltwaters Grassington towards the end of the last Ice Age Cross the stile, and follow the when the permafrost prevented 2clear path straight on rising Refreshments: Plenty of choice at steadily up through the woods for Grassington.No facilities en route. the water from seeping down (triangular junction with maypole through the limestone bed-rock. In 275 metres to reach an obvious fork Terrain: Farm tracks and field and old signpost) along the road places, Conistone Dib closes in to in the path, where you follow the paths lead to Grass Wood, and then then almost immediately right little more than a narrow passage right-hand path, rising steadily up a path leads up through the woods again along a track across the beneath towering limestone crags. -

The Carboniferous Bowland Shale Gas Study: Geology and Resource Estimation

THE CARBONIFEROUS BOWLAND SHALE GAS STUDY: GEOLOGY AND RESOURCE ESTIMATION The Carboniferous Bowland Shale gas study: geology and resource estimation i © DECC 2013 THE CARBONIFEROUS BOWLAND SHALE GAS STUDY: GEOLOGY AND RESOURCE ESTIMATION Disclaimer This report is for information only. It does not constitute legal, technical or professional advice. The Department of Energy and Climate Change does not accept any liability for any direct, indirect or consequential loss or damage of any nature, however caused, which may be sustained as a result of reliance upon the information contained in this report. All material is copyright. It may be produced in whole or in part subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgement of the source, but should not be included in any commercial usage or sale. Reproduction for purposes other than those indicated above requires the written permission of the Department of Energy and Climate Change. Suggested citation: Andrews, I.J. 2013. The Carboniferous Bowland Shale gas study: geology and resource estimation. British Geological Survey for Department of Energy and Climate Change, London, UK. Requests and enquiries should be addressed to: Toni Harvey Senior Geoscientist - UK Onshore Email: [email protected] ii © DECC 2013 THE CARBONIFEROUS BOWLAND SHALE GAS STUDY: GEOLOGY AND RESOURCE ESTIMATION Foreword This report has been produced under contract by the British Geological Survey (BGS). It is based on a recent analysis, together with published data and interpretations. Additional information is available at the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) website. https://www.gov.uk/oil-and-gas-onshore-exploration-and-production. This includes licensing regulations, maps, monthly production figures, basic well data and where to view and purchase data. -

16 Grassington 16

16 Grassington 16 Start/Finish Grassington SE 003 636 Distance 19km (12 miles) Off road 9.5km (6 miles) On road 9.5km (6 miles) 50% Ascent 396m (1,300ft) OFF ROAD Grade ▲ Time 2½hrs–3hrs Parking Large car park in Grassington Pub The Fountaine Inn, Linton Café Cobblestones Café (but bring sandwiches as well) We are revising this route to avoid the Grassington Moor area as a mistake was made in the original version of this route. There is no legal right of way for bicycles across the old mine workings above Yarnbury to Bycliffe and this revision avoids this area entirely. The revised route takes the quiet tarmac lane from the heart of Grassington, following the eastern side of the River Wharfe, to the pleasant village of Conistone, where the original route is regained. There is a right of way (Scot Gate Lane) that climbs long and steeply up to Bycliffe from just outside Conistone. It would involve descending the same way you climbed, but the descent (part of the original route) is a fun undertaking. Overview A pleasant ride up the eastern side of the River Wharfe from Grassington to the vil- lage of Conistone. The route crosses the River Wharfe and heads to Kilnsey before climbing out of the dale. A long grassy climb over sheep pasture is followed by fun bridleways and then a good rocky descent towards Threshfield. Quiet roads and easy bridleways are then linked together for the return leg to Grassington. On Scot Gate Lane above Wharfedale 116 Mountain Biking in the Yorkshire Dales 16 Grassington 117 Directions 1 Starting out from the car park at the Yorkshire Dales National Park Authority building in Grassington, turn out of the car park. -

Halton Gill Halton Gill

WALK 10 – HARD: 8 miles and 2,100 feet of climbing (approx) Starting point: Halton Gill Halton Gill – Horse Head Pass – Yockenthwaite – Beckermonds – Eller Carr – Halton Gill Refreshments: Katie’s Cuppas, Halton Gill Directions: From Halton Gill follow the road through the tiny hamlet passing the Reading Room and Katie’s Cuppas Continue to follow the road as it goes around the bend, as the road begins to straighten up take the bridleway on the right hand side signposted Yockenthwaite 3 miles & Beckermonds 2 ½ miles. The grassy path starts to climb steeply and zig-zag slightly. In front are lovely views of Foxup and Cosh Moor. Ignore the path that goes off to the left to Beckermonds, continue climbing upwards (you will be returning via this path). Make sure to look back down to see a great view of Littondale. The path continues for around a mile winding upwards to Horse Head pass. On reaching the gate at the top of Horse Head pass, Horse Head trig point can be seen on your left. At the top on a clear day, looking in a south westerly direction you should be able to make out all the Yorkshire 3 Peaks. Continue to follow the main bridleway as it starts to drop downwards towards Raisgill and Yockenthwaite . Now you should start to see views of Buckden Pike to your right and Yockenthwaite Moor directly in front of you. After crossing the small beck the path levels out for a while before dropping sharply to the road. Follow any of the tracks down to the road. -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 . -

Do Your Wurst

Issue Number 444 December 2017, January 2018 From the Rector Do your wurst In the middle of November the bakery chain Greggs launched an OUR MISSION Advent Calendar. Its publicity campaign included an image depicting A community seeking to live well with God, the three wise men gathered around a crib containing a sausage roll. gathered around Jesus Christ in prayer and fellowship, It is fair to say that reaction was mixed: the social media group and committed to welcome, worship and witness. Christians on Twitter described the advert as ‘disrespectful’; the The Church Office Freedom Association (curiously one might think, given its name) Bolton Abbey, Skipton BD23 6AL called for a boycott of what it described as a ‘sick, anti-Christian 01756 710238 calendar’. On the other hand a member of the clergy commented in [email protected] The Rector a national newspaper that ‘the ability to receive (the calendar) in The Rectory, Bolton Abbey, Skipton BD23 6AL good part is a sign of grace’. 01756 710326 Personally I was mildly amused that a bakery chain was marketing [email protected] an Advent Calendar in the first place (though I was astonished at the Curate 07495 151987 price of £24). As to being offended, I couldn’t really see what the [email protected] fuss was about: I simply do not consider a parody of a nativity scene Website a threat to my faith. A few days before Greggs launched the www.boltonpriory.church advertisement, news began to emerge of the extent and violence of SUNDAY recent attacks on Coptic Christians in Egypt. -

Buckden Art Group About…Kettlewell Scarecrow Festival Retelling…

www.upperwharfedalechurches.org From the Vicar About…Buckden Art Group From the Churches & Villages About…Kettlewell Scarecrow Festival Features Retelling…Adam and Eve Reflections Crossword Try…’Words in Wood’ Contact Us What’s Happening? Puzzle Church Services A Dales Prayer May the Father's grace abound in you as the flowing water of the beck. May the Son's love and hope invigorate you as the rising slopes of fell and dale. May the Spirit's companionship be with you as the glory of the golden meadows. From the (retired) Vicar… No Postcards from the Celtic Dream! grandparent’s garden, when I was a very As I’m sitting writing this letter, I am small boy in the Black Country. I could conscious of the fact that today I should see clearly it in my mind’s eye, as I was have been on a train from Inverness, kneeling down to tamp the bricks into the returning from a week on Orkney, where sand, and could remember clearly things we had planned, amongst other things, to that I hadn’t thought about in more years visit many of the remarkable than I could imagine.Perhaps it was a gift archaeological sites. to me, that I would never have received if we hadn’t been in lockdown? This was our second “COVID–related” cancellation, the first being Easter on What was also interesting, particularly in Iona, where I was supposed to be leading the first couple of months, was the the Easter retreat at Bishop’s House. realisation that everything around me felt clearer and cleaner. -

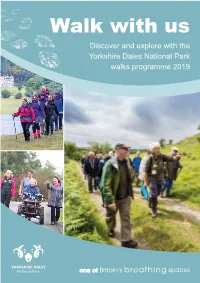

Walk with Us Discover and Explore with the Yorkshire Dales National Park Walks Programme 2019

Walk with us Discover and explore with the Yorkshire Dales National Park walks programme 2019 1 Our walks From pretty villages nestling in lush green valleys to breath taking views of windswept hills, the Yorkshire Dales National Park has it all. And what better way to explore this beautiful area than on one of our special guided walks and events. Each one is led by our experienced, friendly Dales Volunteers who will take you on a wonderful adventure. Come and discover the hidden gems of the Yorkshire Dales with us. Our walks are friendly and relaxed. We aim to provide an interesting and enjoyable introduction to the beautiful landscapes of the National Park, so your walk leader will take the time to point out features of interest along the way, and some walks will include many stopping points. All our walks are taken at a gentle pace; we walk at the speed of the slowest participant, wait for everyone to get over stiles and generally take things easy. How to book: You can book your place through our online shop at www.yorkshiredales.org.uk/ guided-walks or at the National Park Centre nearest to the start of the walk. Contact details for each Centre are: Aysgarth Falls National Park Centre 01969 662910 [email protected] Aysgarth, Leyburn DL8 3TH. Grassington National Park Centre 01756 751690 Malham National Park Centre [email protected] 01729 833200 Hebden Road, Grassington, [email protected] Skipton Malham BD23 5LB. BD23 4DA. Hawes National Park Centre Reeth National Park Centre 01969 666210 01748 884059 [email protected] [email protected] Dales Countryside Museum, Station Yard, Hudson House, Reeth, Burtersett Road, Hawes Richmond, DL8 3NT. -

Society'^Yi^ Dales Uisit of Minister Rosie Winterton to YDS QJ En Wiilson Award Bairman's Report QJ C^ Yorkshire Dales Review Ruswarp: the Paw-Print That No

m m Si _■ ■" •-. Wil, •7'J • .1. ur new President YorkshireSociety'^yi^ Dales Uisit of Minister Rosie Winterton to YDS QJ en Wiilson Award bairman's Report QJ C^ Yorkshire Dales Review Ruswarp: The Paw-print that No. 103 ■ Summer 2008 YorksMreDales Society helped to Save a Railway Journal of the Yorkshire Dales Society In the 1980s Britain's most scenic favourite place. And life went on. railway line, the Settle to Carlisle, was Ruswarp and Graham Nuttaf/ under threat of almost certain closure. Editorial Team: Fleur Speakman with the help of Ann Harding, Bill Mitchell, in happier Garsdale station - remote and lovely - Colin Speakman, Alan Watkinson, Anne Webster and Chris Wright There were just two trains a day and no days is about to be restored to its former freight at all. Today, the line is busier glory by Network Rail. Their decision than ever in its history, open 24 hours a to do that restoration coincided with a day and about to have its capacity letter which appeared in the local Our New President doubled to cope with demand. An press suggesting that FoSCL should amazing turn around! consider a more permanent memorial Saturday May loth 2008 saw Bill Mitchell unanimously Bill from 1951 added the editorship of Cumbria, a magazine to Ruswarp - at Garsdale. elected as Yorkshire Dales Society President at the YDS AGM with its main focus in the Lake District, to his other regular The two people most widely credited at the Dalesbridge Centre in Austwick. Among Bill's many commitments. Presiding over an area from Solway to with forming the group that was to So it is that we have decided to distinctions, was the more unusual one of packing a Number, and from Tyne to Hodder. -

Corporate Branding Along The

Horse Head Moor and Deepdale walk… 5.6 miles t THE NATIONAL TRUST Upper Wharfedale, Yorkshire Dales www.nationaltrust.org.uk/walks Get away from it all and enjoy this invigorating walk up Horse Head Pass and along the remote moorland ridge, with magnificent views of the Three Peaks, returning along the beautiful River Wharfe. The River Wharfe flows some 60 miles through the Dales Start: Yockenthwaite Grid ref: SD904790 Map: OS Landranger 98; this walk requires an from its source at Camm Fell, before joining the River Ouse Ordnance Survey map and it is advisable to bring a compass near Cawood. Look out for Getting here & local facilities Kingfisher, Oystercatcher and Bike: Pennine Cycleway, signed on-road route near Kettlewell (around 5 miles from Dipper by the water’s edge. Buckden), see www.sustrans.org.uk . Off-road cycling is permitted on bridleways Bus/Train: Pride of the Dales 72, Skipton station to Buckden. Service 800/5 from Leeds station and Ilkley station (Sunday, April-October) Road: 3 miles northwest of Buckden, off the B6160. Parking on left-hand side of road, Pen Y Ghent rises steeply on between Raisgill and Yockenthwaite the far side of Littondale, with Car parks, WCs, cafés, pubs and accommodation in Buckden and Kettlewell (not NT). flat-topped Ingleborough Exhibition of the River Wharfe at Town Head Barn, Buckden (NT). Trail maps available beyond Ribblesdale. from the Yorkshire Dales National Park Centre in Grassington, or the National Trust estate Whernside, the third of the office in Malham Tarn. Three Peaks, is on the right. -

Explore Upper Wharfedale

SWALEDALE Buckden UPPER CUMBRIA UPPER WENSLEYDALE WHARFEDALE LOWER WENSLEYDALE Horton Kettlewell UPPER RIBBLESDALE WHARFEDALE Stainforth MALHAMDALE Grassington Settle LOWER WHARFEDALE Explore Upper Wharfedale History and archaeology of Upper Wharfedale Upper Wharfedale is a classic u-shaped glacial valley. When the last glacier melted it briefly left behind a lake. Even today, the valley bottom is prone to flooding and in the past, the marshy ground meant that there were limited bridging points and that roads had to run along the valley sides. The settlement pattern today consists mostly of valley based villages situated at the foot of side valleys. There are few isolated farmsteads. The earliest evidence for people in the dale are the numerous flint weapons and tools that have been collected over the years as chance finds. There is also a much-mutilated Neolithic round barrow. The valley sides and tops have been farmed extensively since at least the Bronze Age. The area is notable for the survival of vast prehistoric and Romano-British farming landscapes, from tiny square ‘Celtic’ fields for growing crops to huge co-axial field systems running in parallel lines up to the top of the valley sides, probably used for farming cattle and sheep. Bronze Age burial cairns are another feature of the landscape. There are few clues about life in the dale just after the Roman period. A 7th century AD female burial near Kettlewell and the chance find of an Anglo-Saxon reliquary shows a continuing spiritual life while Tor Dyke at the entrance to Coverdale above Kettlewell is evidence for the early establishment of territorial boundaries.