CS Lewis on the Incomparable Christ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Web Version Inklings Interior.Pmd

54 Copyright © 2004 The Center for Christian Ethics at Baylor University Permanent Things BY J. DARYL CHARLES The Inklings, because they were profoundly out of step with their times, could offer a penetrating critique of contemporary culture and a lucid defense of Christian basics. The wisdom of their vantage point is what T. S. Eliot calls “the permanent things”—those features of the moral order to the cosmos that in turn hold all cultures and eras accountable. ome of the most fertile Christian thinkers in the twentieth century were profoundly out of step with their times. Indeed, their tendency Sto buck “conventional wisdom” causes writers such as the Inklings, but also Dorothy Sayers, G. K. Chesterton, T. S. Eliot, and Evelyn Waugh, to retain immense popularity among North American Christians. These lit- erary prophets offered a penetrating critique of contemporary culture and a lucid defense of Christian basics couched in imaginative and morally rich language. They had a knack for stressing “the permanent things.” While many of their contemporaries, in ways familiar to us, measured intellectual sophisti- cation by how much moral reality they could deny, these poetic apologists were devoted to seeing how much they might recover. While their contemporaries were obsessed with the politics of power, they upheld principle and were supremely sensitive to the need to align themselves with the eternal and the unchanging. C. S. Lewis distinguished between the older approach and the contemporary fashion: “For the wise men of old the cardinal problem had been how to conform the soul to reality, and the solution had been knowledge, self-discipline, and virtue. -

Surrounded! “C. S. LEWIS: SURPRISED by JOY!”

June 21, 2015 Surrounded! “C. S. LEWIS: SURPRISED BY JOY!” Rev. Gary Haller First United Methodist Church Birmingham, Michigan John 16:19-22 Jesus knew that they wanted to ask him, so he said to them, “Are you discussing among yourselves what I meant when I said, ‘A little while, and you will no longer see me, and again a little while, and you will see me’? Very truly, I tell you, you will weep and mourn, but the world will rejoice; you will have pain, but your pain will turn into joy. When a woman is in labor, she has pain, because her hour has come. But when her child is born, she no longer remembers the anguish because of the joy of having brought a human being into the world. So you have pain now; but I will see you again, and your hearts will rejoice, and no one will take your joy from you.” Matthew 13:44 “The kingdom of heaven is like treasure hidden in a field, which someone found and hid; then in his joy he goes and sells all that he has and buys that field.” “Once there were four children whose names were Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy. This story is about something that happened to them when they were sent away from London during the war because of the air-raids. They were sent to the house of an old Professor who lived in the heart of the country, ten miles from the nearest railway station and two miles from the nearest post office.” Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy soon realize that they have a lot of freedom due to the lack of supervision and decide to play a game of hide and seek in the house. -

The Face of the Materialist Magician: Lewis, Tolkien, and the Art of Crossing Perilous Streets

Volume 35 Number 1 Article 2 10-15-2016 The Face of the Materialist Magician: Lewis, Tolkien, and the Art of Crossing Perilous Streets Robert Boenig Texas A&M University in College Station, TX Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Boenig, Robert (2016) "The Face of the Materialist Magician: Lewis, Tolkien, and the Art of Crossing Perilous Streets," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 35 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol35/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Plenary address, Mythcon 47. Concerns the character of the “Materialist Magician” (Screwtape’s term) in Tolkien and Lewis—the Janus-like figure who looks backward to magic and forward to scientism, without the moral core to reconcile his liminality. -

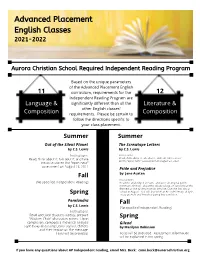

Required Independent Reading Program

Advanced Placement English Classes 2021-2022 Aurora Christian School Required Independent Reading Program Based on the unique parameters of the Advanced Placement English 11 curriculum, requirements for the 12 Independent Reading Program are Language & significantly different than all the Literature & other English classes' Composition requirements. Please be certain to Composition follow the directions specific to your class placement. Summer Summer Out of the Silent Planet The Screwtape Letters by C.S. Lewis by C.S. Lewis Instructions: Instructions: Read, think about it, talk abut it, and take Read, think about it, talk abut it, and take notes to use on the "open-note" assessment on August 23, 2021 notes to use on the "open-note" assessment on August 23, 2021 Pride and Prejudice Fall by Jane Austen Instructions: (No specified Independent Reading) Read the unabridged version, and write an original poem - minimum 30 lines - about the ideals, values, or concerns of the Bennets or the society in which they live. Due the first day of school in August. You will also write an AP style literary analysis Spring essay on Pride and Prejudice during first semester. Perelandra Fall by C.S. Lewis (No specified Independent Reading) Instructions: Read specified chapters weekly, prepare "Wisdom Chair" discussion points. Upon Spring completion, compose a rhetorical analysis Gilead style essay discussing Lewis' stylistic choices by Marilynn Robinson and their impact on the message. Texts will be provided. Texts will be provided. Assessment information will be explained in the spring. If you have any questions about AP Independent reading, email Mrs. Beck: [email protected].. -

Ryan Hudson Honors Thesis-May 2021

! ! ! ! ! ! "#$%&"'%! ()*+,-,.)+,/0!,/!'*1)+,2/! &3)/!45!67892/! :,*1-+2*;!:*5!<,-=)1>!?2>13! ! ! @A1/!#)*B,1>8!=)9!2B+1/!C11/!.*191/+18!)9!)/!,/+1>>1-+7)>!2..2/1/+!2B!'5!$5! D1A,9E!C7+!+=,9!B),>9!+2!)--27/+!B2*!+=1!-2F.>1F1/+)*3!+=1F19!+=)+!)..1)*!,/!+=1!A2*G9!2B! +=191!+A2!B*,1/89E!.)*+,-7>)*>3!+=1F19!*10)*8,/0!=7F)/,+3!,/!+=1!H1A!'*1)+,2/5!@A1/! #)*B,1>8!-2/9+*7-+9!)/!)--27/+!2B!=7F)/!=,9+2*3!,/!+1*F9!2B!=7F)/,+3I9!*1>)+,2/9=,.!+2! /)+7*1E!+*)-,/0!.)++1*/9!)/8!+=1F19!+=)+!>1)8!7.!+2!)/8!+=1/!0*2A!27+!B*2F!+=1!J/-)*/)+,2/! 2B!'=*,9+5!@/!+=1!2+=1*!=)/8E!'5!$5!D1A,9!A*,+19!2B+1/!)C27+!+=1!H1A!'*1)+,2/E!C7+!=1! -2/9,9+1/+>3!1F.=)9,K19!+=1!F39+1*3!2B!A=)+!,9!+2!-2F15!#3!)..>3,/0!#)*B,1>8I9!,81)!2B! +=1!1L2>7+,2/!2B!-2/9-,279/199!+2!+=1!M719+,2/9!D1A,9!*),919!*10)*8,/0!+=1!H1A!'*1)+,2/E! +=,9!+=19,9!),F9!+2!81F2/9+*)+1!+=1!*,-=!+=1F19!+=)+!+=1!A2*G9!2B!+=191!+A2!A*,+1*9!8*)A! 27+!B*2F!2/1!)/2+=1*5!%2!+=,9!1/8E!+=1!+=19,9!A,>>!C10,/!A,+=!)/!1N.>)/)+,2/!2B!#)*B,1>8I9! !"#$%&'()*'+,,*"-"%.*/E!B2>>2A18!C3!)/!)..>,-)+,2/!2B!#)*B,1>8I9!7/81*9+)/8,/0!+2! D1A,9I9!+*1)+F1/+!2B!+=1!H1A!67F)/,+3!,/!0*-*'1)-$/($"%$(2E!,/+1*.*1+18!)--2*8,/0!+2! D1A,9I9!2+=1*!A2*G9!C2+=!,/!B,-+,2/!O3)*'1)-4%$.5*/'46'7"-%$"!)/8!3)"('8$9*4:/' !(-*%&()P!)/8!,/!/2/B,-+,2/!O0*-*'1)-$/($"%$(2')/8!0$-".5*/P5!%=,9!)..>,-)+,2/!>1)89!+2!)/! 1N.)/9,L1!)/8!,F)0,/)+,L1!7/81*9+)/8,/0!2B!+=1!H1A!'*1)+,2/!)9!C2+=!)!.*191/+!)/8!)! B7+7*1!*1)>,+35!! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! "((&@QR:!#S!:J&R'%@&!@?!6@H@&$!%6R$J$;! ! ! ! !!!!!!TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT! -

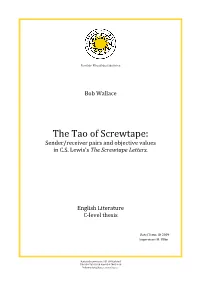

The Tao of Screwtape: Sender/Receiver Pairs and Objective Values in C.S

Estetisk- Filosofiska fakulteten Bob Wallace The Tao of Screwtape: Sender/receiver pairs and objective values in C.S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters. English Literature C-level thesis Date/Term: Ht 2009 Supervisor: M. Ullén Karlstads universitet 651 88 Karlstad Tfn 054-700 10 00 Fax 054-700 14 60 [email protected] www.kau.se Title: The Tao of Screwtape: An examination of sender/receiver pairs for awareness of and relationship to a doctrine of objective values in C.S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters. Author: Bob Wallace Eng C, HT 2009 Pages: 15 Abstract: The purpose of this essay is to identify the various sender/receiver pairs from C.S. Lewis’s novel The Screwtape Letters and, once identified, to examine these pairs within the context of the concept of a doctrine of universal values which is expressed in Lewis’s The Abolition of Man. For the sake of clarity and simplicity the essay begins with a definition of terms and concepts that will be used throughout, including basic terms used when discussing a communicative act: sender, receiver and message. I then explain the essays central concept which is taken from another one of Lewis’s works The Abolition of Man regarding a doctrine of objective value. The idea that a set of universal values exists is often central to secular writing and C.S Lewis, a Christian apologist, makes it clear that he believes that there exists an ethical way of living that is common to all men, Christian and non- Christian alike. He dubs this set of basic morals the Tao. -

{PDF} C. S. Lewis Signature Classic: Mere Christianity

C. S. LEWIS SIGNATURE CLASSIC: MERE CHRISTIANITY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK C. S. Lewis | 256 pages | 12 Apr 2012 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007461219 | English | London, United Kingdom C. S. Lewis Signature Classic: Mere Christianity PDF Book With brilliantly designed, striking new covers, this beautiful boxed collection is a Christian library essential. Overcomer Movie. Lewis related his profound loss in A Grief Observed , which he published under a pseudonym. Each worth reading in its own right. Add to Wishlist. Condition: new. Published by HarperOne Lewis Signature Classics. C S Lewis. Date of Death: November 22, But, it's not incomprehensible. They did not mean, of course, that you might not find an odd individual here and there who did not know it, just as you find a few people who are colour-blind or have no ear for a tune. C S Lewis was one of the intellectual giants of the 20th century and arguably the most influential Christian writer of his day. Lewis however approaches the theme of Mere Christianity with the eye of a storyteller. Copyright c by C. Feb 29, Linda rated it it was amazing. If everyone else became equally rich, or clever, or good-looking there would be nothing to be proud about. For centuries people have been tormented by one question above all - 'If God is good and all-powerful, why does he allow his creatures to suffer pain? You may say that the Father has forgiven us because Christ died for our sins. Brought together in one volume, here are the signature spiritual works of one of the most celebrated literary figures of our time. -

Fiction and Philosophy: the Ideas of C

Kirkwood: Fiction and Philosophy: The Ideas of C. S. Lewis Fiction and Philosophy: The Ideas of C. S. Lewis Elizabeth Kirkwood Oglethorpe University Presented at the 22nd Annual Conference of the Association of Core Texts and Courses, April 2016 It is not surprising that C. S. Lewis, the author Theof Chronicles of Narnia, would also dabble in the realm of science fiction. Lewis uses the power of narrative in the third book of his sci-fi trilogy,That Hideous Strength, to give flesh to the philosophical ideas he writes about in his non-fiction work,The Abolition of Man. Lewis confirms and critiques several philosophical ideas when he writes The Abolition of Man and That Hideous Strength, including those of Aristotle and Hobbes. InThat Hideous Strength, many of the examinations of these ideas are revealed through the character Mark Studdock, in part because he is an intellectual, and in part because his character arc is perhaps the most dramatic within the narrative. For the most part, however, Lewis uses the exploratory nature of the science fiction genre to play out the potential consequences of Hobbes’ ideas, while affirming his own position as espoused inThe Abolition of Man, and that of Aristotle. In both hisPolitics and The Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle speaks at length about life’s purpose being the instilling and pursuit of virtue (Aristotle 77). He believes that virtue is an end in and of itself. Lewis references Aristotle’s philosophy in The Abolition of Man, when he writes about the basic "doctrine of objective value” (Lewis 18) that provides the evaluation of truth. -

Myth in CS Lewis's Perelandra

Walls 1 A Hierarchy of Love: Myth in C.S. Lewis’s Perelandra A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the School of Communication In Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in English by Joseph Robert Walls May 2012 Walls 2 Liberty University School of Communication Master of Arts in English _______________________________________________________________________ Thesis Chair Date Dr. Branson Woodard, D.A. _______________________________________________________________________ First Reader Date Dr. Carl Curtis, Ph.D. _______________________________________________________________________ Second Reader Date Dr. Mary Elizabeth Davis, Ph.D. Walls 3 For Alyson Your continual encouragement, support, and empathy are invaluable to me. Walls 4 Contents Introduction......................................................................................................................................5 Chapter 1: Understanding Symbol, Myth, and Allegory in Perelandra........................................11 Chapter 2: Myth and Sacramentalism Through Character ............................................................32 Chapter 3: On Depictions of Evil...................................................................................................59 Chapter 4: Mythical Interaction with Landscape...........................................................................74 A Conclusion Transposed..............................................................................................................91 Works Cited ...................................................................................................................................94 -

Joy Davidman Lewis: Author, Editor and Collaborator

Volume 22 Number 2 Article 3 1998 Joy Davidman Lewis: Author, Editor and Collaborator Diana Pavlac Glyer Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Glyer, Diana Pavlac (1998) "Joy Davidman Lewis: Author, Editor and Collaborator," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 22 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol22/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Biography of Joy Davidman Lewis and her influence on C.S. Lewis. Additional Keywords Davidman, Joy—Biography; Davidman, Joy—Criticism and interpretation; Davidman, Joy—Influence on C.S. Lewis; Davidman, Joy—Religion; Davidman, Joy. Smoke on the Mountain; Lewis, C.S.—Influence of Joy Davidman (Lewis); Lewis, C.S. -

An Introduction to Christian Apologetics (1948)

Christianity has never lacked articulate defenders, but many people today have forgotten their own heritage. Rob Bowman’s book offers readers of all backgrounds an easy point of entry to this deep and vibrant literature. I wish every pastor knew at least this much about the faithful thinkers of past generations! Timothy McGrew Professor of Philosophy, Western Michigan University Director, Library of Historical Apologetics This is a fantastic little book, written by the perfect person to write it. Bowman’s new Faith Thinkers offers a helpful “Who’s Who” of the great Christian apologists of history and is an excellent resource for students of apologetics! James K. Dew President, New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary Finally—an accessible introduction to many of history’s most in- fluential defenders of the Christian faith and their legacy. Always interesting (and often surprising), Robert Bowman’s Faith Thinkers will give a new generation of readers a greater appreciation for the remarkable men who laid the groundwork for today’s apologetics renaissance. Highly recommended. Paul Carden Executive Director, The Centers for Apologetics Research (CFAR) Faith Thinkers 30 Christian Apologists You Should Know Robert M. Bowman Jr. President, Faith Thinkers Inc. CONTENTS Introduction: Two Thousand Years of Faith Thinkers . 9 Part One: Before the Twentieth Century 1. Luke Acts of the Apostles (c. AD 61) . 15 2. Justin Martyr First Apology (157) . .19 3. Origen Against Celsus (248) . .22 4. Augustine The City of God (426) . 25 5. Anselm of Canterbury Proslogion (1078) . .29 6. Thomas Aquinas Summa Contra Gentiles (1263) . .33 7. John Calvin Institutes of the Christian Religion (1536) . -

Edmund Pevensie As an Example of Lewis's 'New Kind of Man'

Inklings Forever: Published Colloquium Proceedings 1997-2016 Volume 6 A Collection of Essays Presented at the Sixth Frances White Ewbank Colloquium on Article 12 C.S. Lewis & Friends 5-29-2008 A Redeemed Life: Edmund Pevensie as an Example of Lewis's 'new kind of man' Pamela L. Jordan Taylor University Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Jordan, Pamela L. (2008) "A Redeemed Life: Edmund Pevensie as an Example of Lewis's 'new kind of man'," Inklings Forever: Published Colloquium Proceedings 1997-2016: Vol. 6 , Article 12. Available at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever/vol6/iss1/12 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for the Study of C.S. Lewis & Friends at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inklings Forever: Published Colloquium Proceedings 1997-2016 by an authorized editor of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Redeemed Life: Edmund Pevensie as an Example of Lewis's 'new kind of man' Pamela L. Jordan A recurring theme in The Chronicles of excitement and eagerness to explore, likening their Narnia is that Narnia changes those who enter. The new adventure to being shipwrecked (he had read all narrator repeatedly notes the restorative power of the right books). Just as the debate about eating the Narnia and calls the reader's attention to the sandwiches brings tempers to a boil, Edmund is able difference in the children (and adults in The to diffuse the situation with his adventuresome spirit.