Music Licensing in the 21St Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Pays Soundexchange: Q1 - Q3 2017

Payments received through 09/30/2017 Who Pays SoundExchange: Q1 - Q3 2017 Entity Name License Type ACTIVAIRE.COM BES AMBIANCERADIO.COM BES AURA MULTIMEDIA CORPORATION BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX MUSIC BES ELEVATEDMUSICSERVICES.COM BES GRAYV.COM BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IT'S NEVER 2 LATE BES JUKEBOXY BES MANAGEDMEDIA.COM BES MEDIATRENDS.BIZ BES MIXHITS.COM BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES MUSIC CHOICE BES MUSIC MAESTRO BES MUZAK.COM BES PRIVATE LABEL RADIO BES RFC MEDIA - BES BES RISE RADIO BES ROCKBOT, INC. BES SIRIUS XM RADIO, INC BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES STARTLE INTERNATIONAL INC. BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STORESTREAMS.COM BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES TARGET MEDIA CENTRAL INC BES Thales InFlyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES SIRIUS XM RADIO, INC CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT MUSIC CHOICE PES MUZAK.COM PES SIRIUS XM RADIO, INC SDARS 181.FM Webcasting 3ABNRADIO (Christian Music) Webcasting 3ABNRADIO (Religious) Webcasting 8TRACKS.COM Webcasting 903 NETWORK RADIO Webcasting A-1 COMMUNICATIONS Webcasting ABERCROMBIE.COM Webcasting ABUNDANT RADIO Webcasting ACAVILLE.COM Webcasting *SoundExchange accepts and distributes payments without confirming eligibility or compliance under Sections 112 or 114 of the Copyright Act, and it does not waive the rights of artists or copyright owners that receive such payments. Payments received through 09/30/2017 ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting ACRN.COM Webcasting AD ASTRA RADIO Webcasting ADAMS RADIO GROUP Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting ADORATION Webcasting AGM BAKERSFIELD Webcasting AGM CALIFORNIA - SAN LUIS OBISPO Webcasting AGM NEVADA, LLC Webcasting AGM SANTA MARIA, L.P. -

Vol. 80 Thursday, No. 185 September 24, 2015

Vol. 80 Thursday, No. 185 September 24, 2015 Pages 57509–57692 OFFICE OF THE FEDERAL REGISTER VerDate Sep 11 2014 19:01 Sep 23, 2015 Jkt 235001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\24SEWS.LOC 24SEWS tkelley on DSK3SPTVN1PROD with WS II Federal Register / Vol. 80, No. 185 / Thursday, September 24, 2015 The FEDERAL REGISTER (ISSN 0097–6326) is published daily, SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Monday through Friday, except official holidays, by the Office PUBLIC of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Register Subscriptions: Act (44 U.S.C. Ch. 15) and the regulations of the Administrative Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 Committee of the Federal Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Assistance with public subscriptions 202–512–1806 Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office, Washington, DC 20402 is the exclusive distributor of the official General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 edition. Periodicals postage is paid at Washington, DC. Single copies/back copies: The FEDERAL REGISTER provides a uniform system for making Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Assistance with public single copies 1–866–512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and (Toll-Free) Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general FEDERAL AGENCIES applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published Subscriptions: by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public interest. Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions: Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Email [email protected] Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the Phone 202–741–6000 issuing agency requests earlier filing. -

In Re Pandora Media, Inc., 6 F. Supp. 3D 317 (S.D.N.Y. 2014)

IN RE PANDORA MEDIA, INC. 317 Cite as 6 F.Supp.3d 317 (S.D.N.Y. 2014) 225 F.Supp.2d 190, 213 (N.D.N.Y.2002) sonable fees and terms for through-to-the- (‘‘In order to hold an individual liable un- audience (TTTA) blanket license to per- der [the aiding and abetting provision], TTT form musical compositions in repertoire of plaintiff must also show that the individual performing-rights organization (PRO), aided or abetted a primary violation of the pursuant to consent decree. The court pro- [NYS]HRL committed by another employ- hibited PRO from withdrawing rights from ee or the business itself.’’ (alterations in petitioner to perform any compositions original) (internal quotation marks omit- over which PRO retained any licensing ted)). Because plaintiff’s underlying retal- rights, 2013 WL 5211927. iation claim under NYSHRL has been dis- missed or otherwise abandoned, any claim Holdings: After conducting a bench trial, she seeks to assert against Heifferon as an the District Court, Denise Cote, J., held aider and abettor of such alleged retaliato- that: ry conduct fails as a matter of law. (1) TTTA blanket license rate of 1.85% of Plaintiff’s claims under NYSHRL revenue was reasonable for every year against Heifferon in her individual capacity of license term and are dismissed. (2) service was not entitled to rate of IV. CONCLUSION 1.70% of revenue. For all of the foregoing reasons, Defen- Ordered accordingly. dants’ motion for summary judgment dis- missing the Amended Complaint in its en- tirety is granted. 1. Copyrights and Intellectual Property IT IS SO ORDERED. -

Get the Facts: Pandora Buys Fm Radio Station in A

GET THE FACTS: PANDORA BUYS FM RADIO STATION IN A BID TO UNDERCUT SONGWRITERS Pandora recently purchased radio station KXMZ-FM in Rapid City, South Dakota, in a bid to lower the licensing fees it pays songwriters and composers for public performances of their work. Pandora says this will help music creators and listeners, but the facts tell a much different story. SONGWRITERS DRIVE HUGE REVENUES FOR PANDORA • Pandora, a Wall Street-traded company, reported revenues of more than $920 million in FY2014 alone.1 • In contrast, ASCAP is a membership organization that operates on a not-for-profit basis to collect and distribute royalties to the more than 525,000 independent songwriters, composers and music publishers it represents.2 • Every 1,000 plays of a song on Pandora is worth about 9 cents in performance rights for its songwriters, composers and publishers ($0.00009 per stream). 3 • To put that in context, Miranda Lambert’s hit song “The House that Built Me” was streamed on Pandora nearly 22 million times, earning its songwriters and publishers roughly $1,788.48. Co-writer Allen Shamblin received only $894.14. Lady Antebellum’s 2011 Grammy-winning Song of the Year “Need You Now” was streamed nearly 72 million times on Pandora, earning its four songwriters and publishers $5,918.28. Co-writer Josh Kear received only $1,479.57. 4 • In 2014, Pandora paid all songwriters only about $36 million in total royalties, representing a mere 4% of the company’s revenue.5 PANDORA USES MORE MUSIC THAN TRADITIONAL RADIO • Internet radio and traditional AM/FM radio use music and generate revenue in very different ways. -

Exhibit 2181

Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 4 Electronically Filed Docket: 19-CRB-0005-WR (2021-2025) Filing Date: 08/24/2020 10:54:36 AM EDT NAB Trial Ex. 2181.1 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 2 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.2 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 3 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.3 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 131 Filed 03/23/20 Page 4 of 4 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.4 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 132 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 1 NAB Trial Ex. 2181.5 Exhibit 2181 Case 1:18-cv-04420-LLS Document 133 Filed 04/15/20 Page 1 of 4 ATARA MILLER Partner 55 Hudson Yards | New York, NY 10001-2163 T: 212.530.5421 [email protected] | milbank.com April 15, 2020 VIA ECF Honorable Louis L. Stanton Daniel Patrick Moynihan United States Courthouse 500 Pearl St. New York, NY 10007-1312 Re: Radio Music License Comm., Inc. v. Broad. Music, Inc., 18 Civ. 4420 (LLS) Dear Judge Stanton: We write on behalf of Respondent Broadcast Music, Inc. (“BMI”) to update the Court on the status of BMI’s efforts to implement its agreement with the Radio Music License Committee, Inc. (“RMLC”) and to request that the Court unseal the Exhibits attached to the Order (see Dkt. -

FCC-15-129A1.Pdf

Federal Communications Commission FCC 15-129 Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Pandora Radio LLC ) ) Petition for Declaratory Ruling Under Section ) MB Docket No. 14-109 310(b)(4) of the Communications Act of 1934, as ) Amended ) ) ) Application of Connoisseur Media Licenses, LLC ) KXMZ(FM), Box Elder, SD for Consent to Assign Station KXMZ(FM), Box ) FCC File No. BALH-20130620ABJ Elder, South Dakota, to Pandora Radio LLC ) Facility ID No. 164109 ) ORDER ON RECONSIDERATION Adopted: September 16, 2015 Released: September 17, 2015 By the Commission: I. INTRODUCTION 1. In this Order on Reconsideration, we deny the petition for reconsideration (“Declaratory Ruling Petition”) filed by the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (“ASCAP”) on June 3, 2015, seeking reconsideration of the Commission’s declaratory ruling (“Declaratory Ruling”) in the above-captioned docket, released on May 4, 2015.1 In the Declaratory Ruling, the Commission held that it would serve the public interest to permit a widely dispersed group of shareholders to hold aggregate foreign ownership in Pandora Media, Inc. (“Pandora Media”) in excess of the 25 percent benchmark set out in Section 310(b)(4) of the Communications Act of 1934, as amended (“Act”), subject to certain specified conditions.2 We also deny the petition for reconsideration (“Assignment Petition”) filed by ASCAP on July 2, 2015, of the Media Bureau’s (“Bureau”) June 2, 2015, letter decision (“Letter Decision”) granting the above-captioned application (“Assignment Application”) to assign the license of Station KXMZ(FM), Box Elder, South Dakota (“Station”), from Connoisseur Media Licenses, LLC (“Connoisseur”) to Pandora Radio LLC (“Pandora Radio”).3 The Assignment Petition was referred to the 1 Pandora Radio LLC Petition for a Declaratory Ruling Under Section 310(b)(4) of the Communications Act of 1934, as Amended, Declaratory Ruling, 30 FCC Rcd 5094 (2015). -

Nurt Nf Appeals

CTQ-20 16-00001 O!nurt nf Appeals nf tip~ ~tate nf New Vnrk ----+tt+---- FLO & EDDIE, INC., a California Corporation, individually and on behalf of all others similarly situated, Plaintiff-Respondent, -v.- SIRIUS XM RADIO, INC., a Delaware Corporation, Defendant-Appellant. ON CERTIFICATION OF QUESTION BY THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT NOTICE OF MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AS AMICI CURIAE JAMES K. LYNCH (PRO HAC VICE PENDING) BENJAMIN E. MARKS ANDREW M. GASS (PRO HAC VICE PENDING) GREGORY SILBERT LATHAM & WATKINS LLP KAMI LIZARRAGA 505 Montgomery Street, Suite 2000 WElL, GOTSHAL & MANGES LLP San Francisco, California 94111 767 Fifth Avenue Tel.: (415) 391-0600 New York, New York 10153 Fax: (415) 391-8095 Tel.: (212) 310-8000 -and- Fax: (212) 310-8007 JONATHANY. ELLIS (PRO HAC VICE PENDING) Attorneys for Amici Curiae LATHAM & WATKINS LLP Pandora Media, Inc., The Computer & 555 Eleventh Street, NW, Suite 1000 Communications Industry Association, Washington, D.C. 20004 New York State Restaurant Association Tel.: (202) 637-2145 and National Restaurant Association Fax: (202) 637-2200 Attorneys for Amicus Curiae iHeartMedia, Inc. COURT OF APPEALS OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK FLo & EDDIE, INC., A CALIFORNIA CORPORATION, INDIVIDUALLY AND ON BEHALF OF ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY Case No. CTQ-2016-00001 SITUATED, Plaintiff-Respondent, NOTICE OF MOTION FOR -against- LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AS AMICI CURIAE SIRIUS XM RADIO, INC., ADELAWARE CORPORATION, Defendant-Appellant. PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that, upon the annexed Affirmation of Benjamin -

Services Who Have Paid 2016 Annual Minimum Fees Payments Received As of 07/31/2016

Services who have paid 2016 annual minimum fees payments received as of 07/31/2016 License Type Service Name Webcasting 181.FM Webcasting 3ABNRADIO (Christian Music) Webcasting 3ABNRADIO (Religious) Webcasting 70'S PRESERVATION SOCIETY Webcasting 8TRACKS.COM Webcasting A-1 COMMUNICATIONS Webcasting ABERCROMBIE.COM Webcasting ACAVILLE.COM Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting AD ASTRA RADIO Webcasting AD VENTURE MARKETING DBA TOWN TALK RADIO Webcasting ADAMS RADIO GROUP Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting AGM BAKERSFIELD Webcasting AGM NEVADA, LLC Webcasting AGM SANTA MARIA, L.P. *SoundExchange accepts and distributes payments without confirming eligibility or compliance under Sections 112 or 114 of the Copyright Act, and it does not waive the rights of artists or copyright owners that receive such payments. Services who have paid 2016 annual minimum fees payments received as of 07/31/2016 Webcasting AIBONZ Webcasting AIR ALUMNI Webcasting AIR1.COM Webcasting AIR1.COM (CHRISTMAS) Webcasting AJG CORPORATION Webcasting ALL MY PRAISE Webcasting ALLWEBRADIO.COM Webcasting ALLWORSHIP.COM Webcasting ALLWORSHIP.COM (CONTEMPORARY) Webcasting ALLWORSHIP.COM (INSTRUMENTAL) Webcasting ALLWORSHIP.COM (SPANISH) Webcasting ALOHA STATION TRUST Webcasting ALPHA MEDIA - ALASKA Webcasting ALPHA MEDIA - AMARILLO Webcasting ALPHA MEDIA - AURORA Webcasting ALPHA MEDIA - AUSTIN-ALBERT LEA Webcasting ALPHA MEDIA - BAKERSFIELD *SoundExchange accepts and distributes payments without confirming eligibility or compliance under Sections 112 or 114 of the Copyright -

800.275.2840 MORE NEWS» Insideradio.Com

800.275.2840 MORE NEWS» insideradio.com THE MOST TRUSTED NEWS IN RADIO TUESDAY, MAY 5, 2015 Radio experiments with online customization. With web pureplays capturing the lion’s share of online audio listening, some broadcasters are experimenting with reduced online spotloads and giving listeners the ability to customize what they hear. Preliminary data suggests it’s having a positive impact on digital listening. Federated Media’s new “My” personalized streaming audio player allows listeners to tweak the music mix and skip songs, while still hearing the station personalities. The players start with the same music library as the broadcast simulcast. Registered users can skip six songs an hour (three for unregistered listeners) and rate the songs, which affects how often they’re played in that user’s stream. But the custom streams aren’t just online jukeboxes. There are brief voicetracked jock drop-ins and produced branding elements. And though they’re commercial- free for now, the company plans to add a limited number of spots. An auto dealer has signed on as the sponsor for the players in one of its markets. Some Federated stations offer streaming brand extensions — country “K-105”WQHK-FM, Ft. Wayne, IN has separate streams for southern rock, alt country and specific decades. So which stream do listeners prefer? Based on seven weeks of data, 49.8% of listening was to the customizable versions of the stations, compared to 11.2% for the live station streams. Offshoot channels added up to 36.2% of listening. Keep in mind that when a listener hits the “Listen Live” button, it takes them directly to the live station simulcast. -

Broadcast Applications 12/5/2012

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 27878 Broadcast Applications 12/5/2012 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR AMENDMENT RECEIVED WI BR-20120801ABX WTMJ 74096 JOURNAL BROADCAST Amendment filed 11/30/2012 CORPORATION E 620 KHZ WI , MILWAUKEE FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR AMENDMENT RECEIVED ND BRED-20121123ACO KLBF 91457 EDUCATIONAL MEDIA Amendment filed 11/30/2012 FOUNDATION E 89.1 MHZ ND , LINCOLN MN BRED-20121129AIA KBEM-FM 4275 BOARD OF EDUCATION, SPECIAL Amendment filed 11/30/2012 SCHOOL DISTRICT #1 E 88.5 MHZ MN , MINNEAPOLIS AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING TX BAL-20121130AUM KDOK 48950 TOWNSQUARE MEDIA TYLER Voluntary Assignment of License LICENSE, LLC E 1240 KHZ From: TOWNSQUARE MEDIA TYLER LICENSE, LLC TX , KILGORE To: CHALK HILL COMMUNICATIONS, LLC Form 314 Page 1 of 97 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 27878 Broadcast Applications 12/5/2012 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING IL BAL-20121130AYE WIRL 13040 MONTEREY LICENSES, LLC Voluntary Assignment of License E -

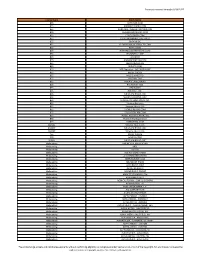

Payments Received Through 09/30/2017 License Type Entity

Payments received through 09/30/2017 License Type Entity Name BES ACTIVAIRE.COM BES AMBIANCERADIO.COM BES AURA MULTIMEDIA CORPORATION BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX MUSIC BES ELEVATEDMUSICSERVICES.COM BES GRAYV.COM BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IT'S NEVER 2 LATE BES JUKEBOXY BES MANAGEDMEDIA.COM BES MEDIATRENDS.BIZ BES MIXHITS.COM BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES MUSIC CHOICE BES MUSIC MAESTRO BES MUZAK.COM BES PRIVATE LABEL RADIO BES RFC MEDIA - BES BES RISE RADIO BES ROCKBOT, INC. BES SIRIUS XM RADIO, INC BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES STARTLE INTERNATIONAL INC. BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STORESTREAMS.COM BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES TARGET MEDIA CENTRAL INC BES Thales InFlyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT SIRIUS XM RADIO, INC CABSAT Stingray Music USA PES MUSIC CHOICE PES MUZAK.COM SDARS SIRIUS XM RADIO, INC Webcasting AMERICANA BREAKDOWN Webcasting KRSL Webcasting 181.FM Webcasting 903 NETWORK RADIO Webcasting A-1 COMMUNICATIONS Webcasting ABERCROMBIE.COM Webcasting ABUNDANT RADIO Webcasting ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting AD ASTRA RADIO Webcasting ADAMS RADIO GROUP Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting AGM BAKERSFIELD Webcasting AGM CALIFORNIA - SAN LUIS OBISPO Webcasting AGM NEVADA, LLC Webcasting AGM SANTA MARIA, L.P. Webcasting AJG CORPORATION Webcasting ALOHA STATION TRUST Webcasting ALPHA MEDIA - ALASKA Webcasting ALPHA MEDIA - AMARILLO Webcasting ALPHA MEDIA - AURORA Webcasting ALPHA MEDIA - AUSTIN-ALBERT LEA Webcasting ALPHA -

Internet Killed the Radio Star

Journal of Intellectual Property Law Volume 23 | Issue 2 Article 6 April 2016 Internet Killed the Radio Star: Preventing Digital Broadcasters from Exploiting the Radio Music License Committee Rate to the Detriment of Songwriters Alexander Reed Speer Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/jipl Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Alexander Reed Speer, Internet Killed the Radio Star: Preventing Digital Broadcasters from Exploiting the Radio Music License Committee Rate to the Detriment of Songwriters, 23 J. Intell. Prop. L. 357 (2016). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uga.edu/jipl/vol23/iss2/6 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Georgia Law. Please share how you have benefited from this access For more information, please contact [email protected]. : Internet Killed the Radio Star: Preventing Digital Broadcasters f INTERNET KILLED THE RADIO STAR: PREVENTING DIGITAL BROADCASTERS FROM EXPLOITING THE RADIO MUSIC LICENSE COMMITTEE RATE TO THE DETRIMENT OF SONGWRITERS Alexander Reed Speer' TABLE OF CONTENTS I. IN TRO DUCTIO N .......................................................................................... 358 II. BA CKG RO UN D ............................................................................................. 361 A. SONGWRITER PUBLIC PERFORMANCE RIGHTS AND PERFORMING RIGHTS ORGANIZATIONS ......................................... 362 B. PANDORA'S ACQUISITION OF KXMZ-FM AND ITS STRATEGY TO ADJUST PUBLIC PERFORMANCE ROYALTAY RATES .................... 365 IH . AN ALYSIS ...................................................................................................... 367 A. THE DANGER OF ALLOWING DIGITAL BROADCASTERS' PURCHASES OF TERRESTRIAL RADIO STATIONS TO ENTITLE THEM TO THE RMLC BROADCAST RATE .........................................