The University As a Source of Reconciled Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fr. Arturo Sosa Superior General Father Arturo Sosa

Fr. Arturo Sosa SUPERIOR GENERAL Father Arturo Sosa Father Arturo Sosa was born in 31 Caracas, Venezuela on 12 Novem- ber 1948. Until his election, Fa- ther Sosa was Delegate for Inter- provincial Houses of the Society in Rome, as well as serving on the General Council as a Counsellor. He obtained a licentiate in philo- sophy from the Andrés Bello Ca- tholic University in 1972. He later obtained a doctorate in Political Science from the Central Univer- sity of Venezuela, in 1990. Father Sosa speaks Spanish, Ita- lian, English, and understands French. In 2008, during General Congregation 35, Father General Adolfo Nicolás appointed FFather Arturo Sosa as General Counsellor, based in Venezuela. In 2014, Father Sosa joi- ned the General Curia community and took on the role of Delegate for Interprovincial Roman Houses of the Society of Jesus in Rome, which include the Pontifical Gregorian University, the Pontifical Biblical Institute, the Pontifical Oriental Institute, the Vatican Observatory, Civiltà Cattolica, as well as international Jesuit colleges in Rome. Between 1996 and 2004, Father Sosa was provincial superior of the Jesuits in Venezuela. Before that, he was the province coordinator for the social apostolate, during which time he was also director of Gumilla Social Center, a center for research and social action for the Jesuits in Venezuela. Father Arturo Sosa has dedicated a large part of his life to research and teaching. He has held different positions in academia. He has been a professor and member of the Council of the Andrés Bello Catholic Foundation and Rector of the Catholic University of Táchira. -

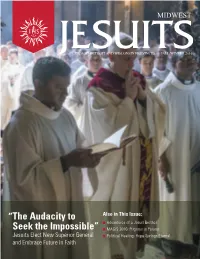

The Audacity to Seek the Impossible” “

MIDWEST CHICAGO-DETROIT AND WISCONSIN PROVINCES FALL/WINTER 2016 “The Audacity to Also in This Issue: n Adventures of a Jesuit Brother Seek the Impossible” n MAGIS 2016: Pilgrims in Poland Jesuits Elect New Superior General n Political Healing: Hope Springs Eternal and Embrace Future in Faith Dear Friends, What an extraordinary time it is to be part of the Jesuit mission! This October, we traveled to Rome with Jesuits from all over the world for the Society of Jesus’ 36th General Congregation (GC36). This historic meeting was the 36th time the global Society has come together since the first General Congregation in 1558, nearly two years after St. Ignatius died. General Congregations are always summoned upon the death or resignation of the Jesuits’ Superior General, and this year we came together to elect a Jesuit to succeed Fr. Adolfo Nicolás, SJ, who has faithfully served as Superior General since 2008. After prayerful consideration, we elected Fr. Arturo Sosa Abascal, SJ, a Jesuit priest from Venezuela. Father Sosa is warm, friendly, and down-to-earth, with a great sense of humor that puts people at ease. He has offered his many gifts to intellectual, educational, and social apostolates at all levels in service to the Gospel and the universal Church. One of his most impressive achievements came during his time as rector of la Universidad Católica del Táchira, where he helped the student body grow from 4,000 to 8,000 students and gave the university a strong social orientation to study border issues in Venezuela. The Jesuits in Venezuela have deep love and respect for Fr. -

Jesuits West Magazine

Spring 2020 JESUITS WEST The Family Visit of Jesuit Superior General Arturo Sosa, SJ Page 13 Provincial’s Jesuit Profiles Novena Donor Profile Kino Border Seeing the Letter of Grace Initiative Opens Invisible New Shelter Page 2 Page 4 Page 8 Page 10 Page 22 Page 24 JESUITS WEST MAGAZINE PROVINCIAL OFFICE Fr. Scott Santarosa, SJ Provincial Fr. Michael Gilson, SJ Socius EDITOR Tracey Primrose Provincial Assistant for Communications DESIGN Lorina Herbst Graphic Designer ADVANCEMENT OFFICE Siobhán Lawlor Provincial Assistant for Advancement Fr. John Mossi, SJ Benefactor Relations Fr. Samuel Bellino, SJ Director of Legacy Planning Patrick Ruff Province Liaison Barbara Gunning Regional Director of Advancement Southern California and Arizona Laurie Gray Senior Philanthropy Officer Northwest Michelle Sklar Senior Philanthropy Officer San Francisco Bay Area Jesuits West is published two times a year by the Jesuits West Province P.O. Box 86010, Portland, OR 97286-0010 www.jesuitswest.org 503. 226 6977 Like us on Facebook at: www.facebook.com/jesuitswest Follow us on Twitter at: www.twitter.com/jesuitswest The comments and opinions expressed in Jesuits West Magazine are those of the authors and editors and do not necessarily reflect official positions of Jesuits West. Cover photo of Superior General Arturo Sosa, SJ, with students from Seattle Nativity School. © 2020 Jesuits West. All rights reserved. Photo credit: Fr. John Whitney, SJ IFC Jesuits West. Spring 2020 JESUITS WEST Spring 2020 Table of Contents Page 2 Provincial’s Letter Page 3 Faith Doing Justice Discernment Series The discernment work continues for Ignatian leaders across the Province. Page 4 Jesuit Profiles Fr. -

Living Tradition EN Edited 31.03.2020 Rev02

Secretariat for Secondary and Pre-secondary Education Society of Jesus Rome Jesuit Schools A Tradition in the 21st century ©Copyright Society of Jesus Secretariat for Education, General Curia, Roma Document for internal use only the right of reproduction of the contents is reserved May be used for purposes consistent with the support and improvement of Jesuit schools It may not be sold for prot by any person or institution Cover photos: Cristo Rey Jesuit College Prep School Of Houston Colégio Anchieta Colegio San Pedro Claver Jesuit Schools: A living tradition in the 21 century An ongoing Exercise of Discernment Author: ICAJE (e International Commission on the Apostolate on Jesuit Education) Rome, Italy, SEPTEMBER 2019, rst edition Version 2, March 2020 Contents 5 ................ Jesuit Schools: A Living Tradition to the whole Society 7 ................ Foreword, the conversation must continue... 10 .............. e current ICAJE Members 11 .............. INTRODUCTION 13 .............. • An Excercise in Discernment 15 .............. • Rooted in the Spiritual Excercises 17 .............. Structure of the Document 19 .............. PART 1: FOUNDATIONAL DOCUMENTS 20 .............. A) e Characteristics of Jesuit Education 1986 22 .............. B) Ignatian Pedagogy: A Practical Approach 24 .............. C) e Universal Apostolic Preferences of the Society of Jesus, 2019 28 .............. D) Other Important Documents 31 .............. PART 2: THE NEW REALITY OF THE WORLD 32 .............. 1) e Socio-Political Reality 40 .............. 2) Education 45 .............. 3) Changes in Religious Practice 47 .............. 4) Changes in the Catholic Church 49 .............. 5) Changes in the Society of Jesus 56 .............. PART 3: GLOBAL IDENTIFIERS OF JESUIT SCHOOLS 57 .............. To act as a universal body with a universal mission 59 .............. 1) Jesuit Schools are committed to being Catholic and to offer in-depth faith formation in dialogue with other religions and worldviews 62 ............. -

Voices of Faith 2017 Arturo Sosa, S.I. Stirring the Waters – Making the Impossible Possible Vatican March 8, 2017

Voices of Faith 2017 Arturo Sosa, S.I. Stirring the Waters – Making the Impossible Possible Vatican March 8, 2017 I would like to thank Voices of Faith and the Jesuit Refugee Service for inviting me to celebrate International Women’s Day with you and all of those gathered here today. I take this opportunity to show my gratitude to the women who will be speaking today, women making a difference in their families and communities, especially in the most remote corners of the world. These are difficult times in our world, and we need to stand and work together as women and men of faith. As you know, the global theme for this year’s celebration of International Women’s Day is Be Bold for Change. Here in Vatican City, physically at the center of the church, Voices of Faith and JRS seek to be Making the Impossible Possible. Especially here in Rome, that is a bold change! I would like to reflect on what making the impossible possible means to me as the leader of the Society of Jesus, as a citizen of the world, and as a member of the Catholic Church. We need to have the faith that gives the audacity to seek the impossible, as nothing is impossible for God. The faith of Mary that opened her heart as a woman to the possibility of something new: to become the Mother of God’s son. JRS: Resilience As you may be aware, I come from Latin America, a continent with millions of displaced people. With almost 7 million, Colombia has the largest number of internally displaced people in the world, and a disproportionate number of them are women and children. -

Fr. General at the International Congress for Jesuit Education Delegates ©Copyright Society of Jesus Secretariat for Education, General Curia, Roma

Secretariat for Secondary and Pre-secondary Education Society of Jesus Rome Highlights of JESEDU-Rio2017 Fr. General at the International Congress for Jesuit Education Delegates ©Copyright Society of Jesus Secretariat for Education, General Curia, Roma Document for internal use only e right of reproduction of the contents is reserved May be used for purposes consistent with the support and improvement of Jesuit schools It may not be sold for prot by any person or institution Highlights of JESEDU-Rio2017 FR. GENERAL AT THE INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS FOR JESUIT EDUCATION DELEGATES Author: Secretariat for Education, Society of Jesus Editor Committee: Fr. José Alberto Mesa, SJ Fr. Johnny Go, SJ Mr. Rafael Galaz Design: Mr. Pablo Foneron Rome, Italy, May 2018, rst edition All images are property of the Society of Jesus, all rights are reserved Index 1 Presentation 2 Interview with Fr. General 3 Context 5 Discerment Paragraph 6 Homily 6 Context 9 Discerment Paragraph 10 Keynote Address 11 Context 24 Discerment Paragraph 25 Conversation 26 Context 33 Discerment Paragraph 34 Action Statement 35 Context 38 Questions 1 Presentation From October 16th to 20th, 2017, the International Congress for Jesuit Education Delegates was held in Rio de Janeiro. e Congress produced many documents: lectures, group work, conversations, reections, syntheses, etc. Among these documents, it is especially worth noting the Action Statement prepared by ICAJE (International Commission on the Apostolate of Jesuit Education) and approved by the delegates. is statement represents the consensus of the participants that emerged during the Congress, and it serves as an important roadmap to developing the global apostolic potential of our secondary and pre-secondary education. -

Jesuit Higher Education: a Journal

Jesuit Higher Education: A Journal Volume 10 Number 1 Article 1 5-2021 Editorial Kari Kloos [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://epublications.regis.edu/jhe Recommended Citation Kloos, Kari. "Editorial." Jesuit Higher Education: A Journal 10, 1 (). https://epublications.regis.edu/jhe/ vol10/iss1/1 This Editorial is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarly and Peer-Reviewed Journals at ePublications at Regis University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jesuit Higher Education: A Journal by an authorized administrator of ePublications at Regis University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kloos: Editorial Editorial Kari Kloos General Editor Professor of Religious Studies and Assistant Vice President for Mission Regis University [email protected] Some words from leaders of the Society of Jesus our work, and dream more creatively and boldly have the power to shape a generation of the for our future. people in Jesuit higher education, and beyond. The question from Fr. Pedro Arrupe, S.J., to the As a member of the Central and Southern Jesuit alumni at Valencia, Spain in 1973—“Have Province (USA) Commission on Ministries in we educated you for justice?”—resonates in Jesuit 2017-18, I witnessed the process of communal universities today as much as it did forty-eight discernment that culminated in the articulation of years ago, calling us to continual growth and the UAPs. Jesuits and their lay co-workers alike transformation.1 So, too, one of the key claims in shared what they valued most about their Jesuit the fourth decree of General Congregation 32 in identity as well as the most pressing needs in their 1975—“[t]he mission of the Society of Jesus today local settings. -

Jesuitas En Venezuela

JESUITASDE VENEZUELA 2 Editorial Arturo Peraza SJ El esfuerzo educativo de los jesuitas en los 100 años 4 de trabajo en Venezuela Francisco Javier Duplá SJ 9 El apostolado seductor de los jesuitas en comunicación Jesús María Aguirre SJ 12 Jesuitas y gobiernos en Venezuela Luis Ugalde SJ Jesuitas y laicos en la Parroquia San Ignacio de Loyola 16 de la ciudad de Maturín Mariano Fuente SJ Edita 18 Jesuitas y laicos en Guayana: la historia de un compromiso Provincia de Venezuela de la José Carlos Blanco Rodríguez Compañía de Jesús Dirección 19 La Red Ignaciana de Lara: un espacio de encuentro Francisco Javier Duplá SJ Piero Trepiccione Coordinación 20 Colaboración de jesuitas y laicos en Mérida Fátima Arévalo González Mireya Escalante Diseño y Diagramación Reyna Contreras M. 24 La CG 36ª: el cuerpo apostólico universal en discernimiento Impresión Arturo Sosa SJ Impresos Miniprés, C.A. 28 “Me enseñó a mirar a Dios en los pobres” Correspondencia Arturo Peraza SJ Oficina Provincia Jesuita 32 IN PACE CHRISTI Apatado Postal 20.182 Gustavo Alberto Sucre Eduardo SJ Caracas 1060-A José María Lasarte Aldama SJ Isidro Gurruchaga Segurola SJ Teléfonos (0212) 2644784/2647864 [email protected] www.jesuitasvenezuela.com Publicación anual Depósito legal: PP198302DC2154 ISSN: 1856-4372 EDITORIAL GRADECIDOS CON EL IOS DE A D Todo este año 2016 nos ha servido para agradecerle al MISERICORDIA INFINITA Señor estos 100 años de presencia de la Compañía de Je- sús en Venezuela luego de la restauración de la misma. La Arturo Peraza SJ llegada en octubre de 1916 de tres jesuitas (dos sacerdotes y un hermano), con la misión de colaborar con la Iglesia venezolana en su reconstitución a través de la formación de su clero, abrió un camino en el cual queremos recono- cer la misericordia de Dios a lo largo del mismo. -

The Scene from Rome: Four Questions with José Mesa, S.J

The scene from Rome: Four questions with José Mesa, S.J. José Mesa, S.J., a visiting professor in Loyola’s School of Education, is in Rome to take part in the Jesuits’ 36th General Congregation. Here, he talks about the election process, the atmosphere in the Italian capital, and how be believes the new Superior General—Father Arturo Sosa Abascal, S.J.—will lead the Society of Jesus. What made the new Superior General stand out from the other Jesuits who were considered for the position? The process of an election of a new Superior General is really very different from any other democratic process or election. There are no candidates or campaigns. Instead we have a period of murmuratio that is actually a process of discernment (looking for God’s will) in which electors have the chance to talk to each other about the kind of leadership needed for the Society of Jesus and possible candidates. This is done in private one-on-one conversations. Campaigns or public conversations are strictly forbidden; members of the congregation can only answer the questions they are asked—volunteering information is prohibited. After four days of murmuratio, the electors gather for the election. Electors clearly saw that Father Sosa brings a broad and a particular experience of being Jesuit in a region of the world in which faith and social justice have been at the center of the Church concerns and debates. “A faith that does justice” summarizes well the mission of the Jesuits today, and Father Sosa has a broad experience in this area as a Jesuit working in social ministries in his native Venezuela. -

From Caracas to Rome: the Story of Arturo Sosa an Interview with the New Superior General of the Society of Jesus Rome, October 16, 2016

1 From Caracas to Rome: The Story of Arturo Sosa An interview with the new Superior General of the Society of Jesus Rome, October 16, 2016. Two days after his election, the communications team of General Congregation 36 sat down with Father General Arturo Sosa to discuss his life and thought. The conversation introduces the new Superior General in a way that is more personal, to Jesuits and the wider Ignatian family around the world. On being elected General of the Society Like all the electors, I arrived at the congregation asking myself who would be the best candidates for the job of General, and obviously, I did not have myself on the list. The first day of murmuratio1, I began to gather information about the delegates I thought were good candidates. The second day I began to sense that some delegates were asking about me or had asked about me. The third day I began to worry because the hints were much more direct, and the fourth even more so. In the final three days I spoke with 60 persons, and many were already asking me about my health. So I began to get the idea, though I was still praying that the companions would take seriously what Saint Ignatius says about entering the election without a predetermined decision. As I saw the votes on the date of the election, things became clearer to me, and I had the profound intuition that in this case I have to trust the judgment of the brothers because I don’t trust my own. -

Jesuits and Social Justice

journal of jesuit studies 6 (2019) 651-675 brill.com/jjs Jesuits and Social Justice Daniel Cosacchi Marywood University [email protected] Abstract This article examines the history of social justice ministries within the Society of Jesus. Despite the fact that the term is fraught by a great disagreement both about its mean- ing and its place within Jesuit apostolates, successive Jesuit general congregations have upheld its importance over the last five decades. Even though what we now consider to be social justice has been a part of Jesuit life since the order’s founding, this paper primarily considers the period 1974–present, so as to coincide with GC 32 (1974–75). Social justice has taken many forms, based both on geography and personal interests of the particular Jesuit in question. The broad term covers issues such as the Jesuit Refugee Service, the Plowshares Movement, justice in higher education, and Homeboy Industries. Finally, the paper concludes by considering two growing edges for the order regarding social justice: the role of women in Jesuit apostolates, and the ecological question. Keywords Jesuit social justice – Catholic social teaching – peacemaking – ecology – General Congregation 32 – Pedro Arrupe – Jesuit Refugee Service – inculturation It would be challenging to identify a topic more fraught with controversy in Jesuit studies than the issue of social justice.1 Merely defining the term would be problematic in the company of even a small group of Jesuits. Nevertheless, the theme has been important—in one guise or another—in the history of the Society, even from the days of the order’s founding. -

Fial Booklet.Indd

Ethiopia Issue No 64 Sep-Oct Nov-Dec 2016 BULLETIN DONA QUARTERLY PUBLICATION BOSCOFROM AET IN THIS ISSUE Editorial 2 The Voice of the Provincial 3 Year of Mercy 4 African Experience 7 7 Salesian World (Global News) 9 Marian Community 10 Rector Major Speaks 11 Salesian World (Local News) 14 Reflecting on Mercy 16 11 Beginning of a New Venture 18 News Vatican 20 Saleisian Family 21 Culture of Vocation Promotion 22 Catholic World 24 16 Mission Animation 25 Print your future 26 Towards a Better World 28 Students’ Corner 29 22 Please Note Editor: Abba Lijo Vadakkan SDB Letters to the editor and articles on Sirituality, Self-help, Graphic Design: Tesfamichael Tsige Bible, Social Concen or even news items from various Email: [email protected] houses are most welcome. All material may be edited for Telephone: +251.931391199 the sake of space or clarity. Pease keep a copy of whatever Website: www.donboscoethiopia.org you send to the Bulletin for publication. We regret we Publishers: Don Bosco Printing Press, cannot return unsolicited articles and photographs. Mekanissa Joel Welden, a famous counselor and psychologist says that one of the strangest seeds in the world is the seed of the Chinese bamboo tree. It lies buried in the soil for five years before any seedling or sprout appears above the ground. Think of it! Five years! During all these five years the seed is cultivated, i.e. watered and fertilized regularly. Just think how frustrating it is! Doing the same things every day, not having any evidence that your efforts are having any effect? The only thing you know is that the result is supposed to come in 4 years.