The Case for Fruit Trees in the City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Heirloom Gardener's Seed-Saving Primer Seed Saving Is Fun and Interesting

The Heirloom Gardener's Seed-Saving Primer Seed saving is fun and interesting. It tells the story of human survival, creativity, and community life. Once you learn the basics of saving seeds you can even breed your own variety of crop! Share your interesting seeds and stories with other gardeners and farmers while helping to prevent heirloom varieties from going extinct forever. Contact The Foodshed Project to find out about local seed saving events! 1. Food “as a system”...........................................................................................................................5 2. Why are heirloom seeds important?.................................................................................................6 3. How are plants grouped and named?...............................................................................................8 4. Why is pollination important?... ......................................................................................................11 5. What is a monoecious or a dioecious plant?....................................................................................12 6. How do you know if a plant will cross-breed?.................................................................................14 7. What types of seeds are easiest to save?........................................................................................18 8. What about harvesting and storing seeds?.....................................................................................20 9. What do I need to know -

Hanson's Garden Village Edible Fruit Trees

Hanson’s Garden Village Edible Fruit Trees *** = Available in Bare Root for 2020 All Fruit Trees Available in Pots, Except Where Noted APPLE TREES Apple trees are not self fertile and must have a pollination partner of a different variety of apple that has the same or overlapping bloom period. Apple trees are classified as having either early, mid or late bloom periods. An early bloom apple tree can be pollinated by a mid bloom tree but not a late bloom tree. A mid bloom period apple could be used to pollinate either an early or late bloom period apple tree. Do not combine a late bloomer with an early bloom period apple. Apple trees are available in two sizes: 1) Standard – mature size 20’-25’ in height and 25’-30’ width 2) Semi-Dwarf (S-M7) – mature size 12’-15’ in height and 15’-18’ width —————————————————————–EARLY BLOOM—————————————————————— Hazen (Malus ‘Hazen’): Standard (Natural semi-dwarf). Fruit large and dark red. Flesh green-yellow, juicy. Ripens in late August. Flavor is sweet but mild, pleasant for eating, cooking and as a dessert apple. An annual bearer. Short storage life. Hardy variety. Does very well without spraying. Resistant to fire blight. Zones 3-6. KinderKrisp (Malus ‘KinderKrisp’ PP25,453): S-M7 (Semi-Dwarf) & Standard. Exceptional flavor and crisp texture, much like its parent Honeycrisp, this early ripening variety features much smaller fruit. Perfect size for snacking or kid's lunches, with a good balance of sweet flavors and a crisp, juicy bite. Outstanding variety for homeowners, flowering early in the season and ripening in late August, the fruit is best fresh from the tree, hanging on for an extended period. -

1 Chapter 1: Introduction and Problem Statement Bees Are Critical to The

1 Chapter 1: Introduction and Problem Statement Bees are critical to the stability and persistence of many ecosystems, and therefore, must be understood and protected (Allen-Wardell et al., 1998; Kearns, Inouye & Waser, 1998; Michener, 2000; Cane, 2001; Kremen, Williams & Thorp, 2002; LeBuhn, Droege & Carboni, in press). Their pollination services are responsible for global biodiversity and maintenance of human food supplies (Allen-Wardell et al., 1998; Kearns et al., 1998; Michener, 2000; Kremen et al., 2002). Over the past two decades, bees have received increased attention by the scientific community because of population declines (Allen-Wardell et al., 1998; Kearns et al., 1998). Scientific research has focused primarily on honey bee ( Apis mellifera ) declines because this species is the most commonly used pollinator in United States agriculture, but significant declines have also occurred in native bees (Kevan and Phillips, 2001; Allen-Wardell et al., 1998). The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Bee Research Laboratory has charted a 25% decline in managed honey bee colonies since the 1980s (Greer, 1999). Estimates on native bee declines, on the other hand, are disputed and vary (Williams, Minckley & Silveira, 2001). Nonetheless, increased anthropogenic effects and exotic pests are impacting global bee populations (Kim, Williams & Kremen, 2006). The specific consequences of the bee population decline on our food supply and global biodiversity remain to be seen, but the effects will inevitably be negative (Allen- Wardell et al., 1998). Fears of food, economic and biological losses have provoked a surge of scientific literature that examines the associated problems. Recent advancements in geography and landscape ecology suggest that landscape composition and pattern are critical to population dynamics (Turner, Gardner & O’Neill, 2001). -

Honey Bees and Climate Change

Abstract of final report Honey Bees and Climate Change Prof. Dr. Frank-M. Chmielewski, Sophie Godow For the western honey bee (Apis mellifera), weather conditions (especially air temperature, but also global radiation, precipitation intensity and wind speed) and availability of nectar are, next to factors like breeding traits and colony health, essential in determining flight activity and with it for pollination and honey yield. Thus, climate changes could affect flight conditions for bees. In Hesse, an increase in the air temperature of 0.6 K was detected compared from the period 1951-1980 to 1981-2010 (HLNUG, 2016). Climate scenarios predict a further increase of 3.9 K on average for the period 2071-2100 compared to the reference period 1971-2000 (REKLIES, 2017). This study examines the impact of a changing climate on honey bee flight and honey yield. The model BIENE, developed by the German Weather Service (Deutscher Wetterdienst, DWD, FRIESLAND, 1998), allows the classification of hours according to their (weather-related) suitability for bee flight (none at all, bad, moderate, good) as well as the calculation of a measure of potential bee flight for freely chosen periods. This purely weather-driven model, however, was not suitable for the assessment of the bee flight during the whole year, because crucial parameters were omitted from the model, especially the phenology of honey plants. The effects of climatic changes of the last decades are clearly visible on the development of these plants, especially in spring. For example, the beginning fruit tree blossom (apple, sweet cherry, sour cherry, pear) in Germany since 1961 has advanced by about 3 days per decade. -

(Megachilidae; Osmia) As Fruit Tree Pollinators Claudio Sedivy, Silvia Dorn

Towards a sustainable management of bees of the subgenus Osmia (Megachilidae; Osmia) as fruit tree pollinators Claudio Sedivy, Silvia Dorn To cite this version: Claudio Sedivy, Silvia Dorn. Towards a sustainable management of bees of the subgenus Osmia (Megachilidae; Osmia) as fruit tree pollinators. Apidologie, Springer Verlag, 2013, 45 (1), pp.88-105. 10.1007/s13592-013-0231-8. hal-01234708 HAL Id: hal-01234708 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01234708 Submitted on 27 Nov 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Apidologie (2014) 45:88–105 Review article * INRA, DIB and Springer-Verlag France, 2013 DOI: 10.1007/s13592-013-0231-8 Towards a sustainable management of bees of the subgenus Osmia (Megachilidae; Osmia) as fruit tree pollinators Claudio SEDIVY, Silvia DORN ETH Zurich, Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Applied Entomology, Schmelzbergstrasse 9/LFO, 8092 Zurich, Switzerland Received 31 January 2013 – Revised 14 June 2013 – Accepted 18 July 2013 Abstract – The limited pollination efficiency of honeybees (Apidae; Apis) for certain crop plants and, more recently, their global decline fostered commercial development of further bee species to complement crop pollination in agricultural systems. -

Choosing Fruit Trees the Just Fruits & Exotics FACTS 30 St

Just Choosing Fruit Trees the Just Fruits & Exotics FACTS 30 St. Frances St. Crawfordville fl 32327 Ph. 850-926-5644 fax 850-926-9885 e-mail [email protected] www.justfruitsandexotics.com CHOOSING the RIGHT VARIETY Many fruit trees like apples, peaches, pears, plums, etc., need a certain amount of winter dormancy (resting phase) to develop their leaves and fruit buds for the coming year. This dormancy period is triggered by colder weather and shorter days, and the tree will stay at rest until it has just the amount of cold weather it needs. Chill hours are a measurement of this period. Here in North Florida our chill hour range is 400 to 600 hours. Choosing the right variety of fruit for your yard is important to successfully getting a crop. In apples, for instance, some high chill varieties like Red Delicious require up to 1400 hours of chill, so they do well only north of the Carolinas. Anna and Dorsett Golden need only 250-300 hours, so are perfect for growers in north and central Florida, in zones 8B-9. So read carefully the zones listed at the end of each fruit description in our website www.justfruitsandexotics.com and make sure you are buying a plant that likes the weather where you live. To Pollinate or Not to Pollinate: That is the Question Good pollination is the one of the key factors to good fruit set. Fruit falls into three pollinating categories: SELF-FERTILE (or SELF-POLLINATING) - this means the variety needs no help or pollen from another variety to set a crop of fruit. -

April 2018 Garden Column Pollination Dr. Robert Nyvall Rfnyvall

April 2018 Garden Column Pollination Dr. Robert Nyvall [email protected] "It is impossible to under estimate the importance of the pollination process. If the bee disappeared off the surface of the globe, then man would have only four years of life left. No more bees, no more pollination, no more plants, no more animals, no more man.” - Albert Einstein Pollinators are what ecologists call keystone species. A keystone keeps the two halves of an arch together. Remove the keystone and the whole arch collapses. Remove pollinators and nature collapses. Therefore pollination is worth billions of dollars and highlights how nature is interconnected. Bees are perhaps the best known pollinators and you can thank a honey bee for one third of your diet. However other pollinators include other insects such as wasps and flies; wind, animals or anything that 'shakes' the pollen onto the stigma. Pollination will affect the types of plants we choose to grow. If you buy an apple tree and no fruit is produced there may be several reasons. One of the most basic is a failure to pollinate. Following is fruit tree pollination 101. Most fruit trees require pollination between two or more trees for fruit to set. A bee, or another pollinator, lands in a flower to feed. Pollen from the flower’s anthers (male part) dusts its body. With pollen clinging to it, the bee flies on to another flower. As the bee feeds, pollen is brushed onto the stigma of the pistil (female part) of the second flower. The stigma is the part of the pistil that receives the pollen during pollination. -

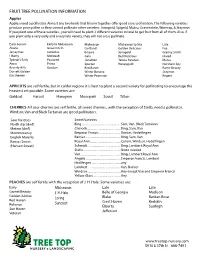

FRUIT TREE POLLINATION INFORMATION Apples Apples Need a Pollinator

FRUIT TREE POLLINATION INFORMATION Apples Apples need a pollinator. Almost any two kinds that bloom together offer good cross pollination. The following varieties produce poor pollen so they cannot pollinate other varieties: Jonagold, Spigold, Mutsu, Gravenstein, Winesap, & Stayman. If you plant one of these varieties , you will need to plant 3 different varieties in total to get fruit from all of them. Also, if you plant only a very early and a very late variety, they will not cross pollinate. Early Season Early to Midseason Midseason Midseason to late Late Akane Gravenstein Cortland Golden Delicious Fuji Jerseymac Jonamac Empire Jonagold Granny Smith Liberty McIntosh Gala Red Delicious Idared Tydean’s Early Paulared Jonathan Yellow Newton Mutsu Anna Prima Spartan Honeygold Northern Spy Beverly Hills Gordon Red Baron Rome Beauty Dorsett Golden Winter Banana Stayman Ein Shemer Winter Pearmain Regent APRICOTS are self fertile, but in colder regions it is best to plant a second variety for pollinating to encourage the heaviest set possible. Some varieties are: Goldcot Harcot Harogem Moorpark Scout Tilton CHERRIES-All sour cherries are self fertile, all sweet cherries , with the exception of Stella, need a pollinator. Windsor, Van and Black Tartarian are good pollinators. Sour Varieties Sweet Varieties North star (dwf) Bing ....................................................Sam, Van, Black Tartarian Meteor (dwf) Chinook .............................................Bing, Sam, Van Montmorency Emperor Francis .............................Rainier, -

Np305accomplishmentreport9-7-06

Table of Contents Contents Page Background and General Information 1 Planning and Coordination for NP 305 2 How This Report was Constructed and What it Reflects 3 Component I: Integrated Production Systems 5 Problem Area Ia - Models and Decisions Aids 5 Problem Area Ib - Integrated Pest Management (IPM) 7 Problem Area 1c - Sustainable Cropping Systems 12 Problem Area 1d - Economic Evaluation 23 Selected Publication ± Component I ± Integrated Production Systems 25 Component II: Agroengineering, Agrochemical, and Related 47 Technologies Problem Area IIa - Automation and Mechanization to Improve Labor 47 Productivity Problem Area IIb - Application Technology for Agrochemicals and 50 Bioproducts Problem Area IIc - Sensor and Sensing Technology 52 Problem Area IId - Controlled Environment Production Systems 54 Problem Area IIe ± Worker Safety and Ergonomics 56 Selected Publications ± Component II - Agroengineering, 57 Agrochemical, and Related Technologies Component III: Bees and Pollination 68 Problem Area IIIa - Pest Management 68 Problem Area IIIb - Bee Management and Pollination 74 Selected Publications - Component III ± Bees and Pollination 80 ARS Research Projects 98 Background and General Information Agricultural research has made the American food and agricultural system the most productive the world has ever known. Crop yields in the United States have increased approximately one percent per year over the last 50 years, which over time has had remarkable impact. In 1890 it took 35 to 40 labor hours to produce 100 bushels of corn, while today that can be accomplished in only 2 hours. This has contributed to the fact that the United States is the world's leading agricultural exporter, and agriculture is the only sector of our economy that provides a positive trade balance to our nation. -

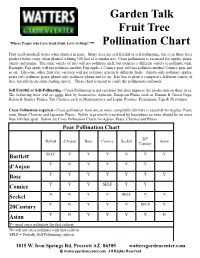

Fruit Tree Pollination Chart

Garden Talk Fruit Tree “Where People who Love fresh Fruit, Love to Shop!” ™ Pollination Chart Fruit treeS producE better when planted in pairs. Many trees are self fruitful or self pollinating, but even these trees product better crops when planted withing 100 feet of a similar tree. Cross pollination is essencial for apples, pears, cherry and plums. The same variety of tree will not pollinate itself, but requires a different variety to pollinate with. Example, Fuji apple will not pollinate another Fuji apple, a Comice pear will not pollinate another Comice pear and so on. Likewise, other fruit tree varieties will not pollinate geneticly different fruits. Apples only pollinate apples, pears only pollinate pears, plums only pollinate plums and so on. It is best to plant a completely different variety of tree, but still in the same fruiting specie. These chart is meant to claify the pollination confusion. Self Fruitful or Self-Pollinating - Cross Pollination is not essential, but does improve the production on these trees. The following trees will set some fruit by themselves. Apricots, European Plums such as Damon & Green Gage, Italian & Stanley Prunes, Tart Cherries such as Montmorency and Lapin, Peaches, Persimmon, Figs & Nectorines. Cross Pollination required - Cross pollination from one or more compatible cultivars is essential for Apples, Pears, most Sweet Cherries and Japanese Plums. Pollen is primarily transfered by honeybees so trees should be no more than 100 feet apart. Below are Cross Pollination Charts for Apples, Pears, Cherries and Plums. Pear Pollination Chart 20 th Barlett d'Anjou Bosc Comice Seckel Asian Century Bartlett SELF Y Y Y N Y Y d'Anjou YNYYYY Bosc YYYYYYY Comice Y Y Y SELF Y Y Seckel N N Y Y SELF Y Y 20Century Y N Y Y Y SELF Y Asian YNYYYYN Y= good cross pollinator for that cultivar N= will not cross pollinate with that cultivar SELF = Partially Self Pollinating cultivar 1815 W. -

Buying Guide (Pdf) Download

DROUGHT DEER TOLERANT RESISTANT Achillea Achillea Aquilegia Aconitum ATTRACT Aster Agastache Coreopsis Ajuga BUTTERFLIES Echinacea Alchemilla Anemone Achillea Gaillardia Aquilegia Ajuga Hemerocallis Artemesia Alcea Hosta Astilbe Alchemilla Iris Bergenia Aquilegia Lavender Brunnera Aster Monarda Campanula Astrantia Papaver Centaurea Bergenia Rudbeckia Chelone Centaurea Russian Sage Convallaria Chelone Sedum Coreopsis Coreopsis Shasta Daisy Delphinium Delphinium Dianthus Dianthus Dicentra Echinacea Digitalis Eupatorium SHADE Echinacea Gaillardia Geum Helenium TOLERANT Helenium Hemerocallis Heuchera Heuchera Aconitum Iris Knautia Aegopodium Lavandula Lavendula Ajuga Liatris Liatris Anemone Lilium Ligularia Astilbe Monarda Lupinus Bergenia Nepata Nepata Convallaria Papaver HERBACEOUS PERENNIAL SELECTION GUIDE Phlox Dicentra HERBACEOUS PERENNIAL SELECTION GUIDE Pulmonaria Rudbeckia Filipendula Salvia Salvia Heuchera Sedum Scabiosa Hosta Sempervivum Sidalcea Lamium Tiarella Solidago Ligularia Veronica Tradescantia Polygonatum Vinca Veronica Primula Pulmonaria 99 HARDINESS ZONE MAP HARDINESS ZONE MAP A zone rating is an attempt to match a plant’s survival with a set of environmental conditions. These conditions include mini- mum winter temperature, frost free period, snow cover, and wind speed. Most zone maps include a list of indicator plant spe- cies whose survival depends on certain climatic variables. Remember that zone ratings are only a guideline for plant selection. Plant survival is also impacted by bodies of water, wind protection, snow cover and urban heat islands. For this reason there will always be trees and shrubs that defy the odds and thrive under conditions very different from their zone rating. Nevertheless, there are limits to this flexibility and in most cases ignoring a plant’s zone rating is an invitation for winter damage. Typical winter damage on woody ornamentals includes winter browning, root injury, tip kill and bole cracking. -

J. Apic. Sci. Vol. 61 No. 1 2017J

DOI 10.1515/JAS-2017-0011 J. APIC. SCI. VOL. 61 NO. 1 2017J. APIC. SCI. Vol. 61 No. 1 2017 Original paper EFFECT OF ARTIFICIAL PROLONGED WINTERING ON EMERGENCE AND SURVIVAL OF OSMIA RUFA ADULTS Karol Giejdasz* Oskar Wasielewski Institute of Zoology, Poznań University of Life Sciences *corresponding author: [email protected] Received: 28 March 2017; accepted: 11 May 2017 Abstract This study discusses the longevity and emergence rate of O. rufa males and females after an extended wintering period in artificial conditions. Experimental activation of the wintering bees was carried out every fifteen days, starting at the end of March and fin- ishing at the beginning of June (25 March, 9 April, 24 April, 9 May, 24 May, 8 June). In our study, the shortest emergence time (5 days) was observed in females that overwintered for at least 220 days and were activated at the beginning of May or later. Their mean emergence time in the last three terms was similar and ranged from 4.6 to 5.1 days. Prolonged wintering increased female emergence dynamics in May and June. Half of the emerged males in our study lived up to 28 days when activated during the first term, and up to 15 days when activated during the last one. In females, half of the bees lived up to 64 and 20 days, respectively. Keywords: emergence, longevity, Osmia rufa, overwintering, survival INTRODUCTION et al. 2011; Pitts-Singer & Cane 2011). The most numerous species come from Osmia genus and Worldwide decline in pollinator abundance and are mostly managed for fruit tree pollination diversity has been observed in the agricul- (Bosch & Kemp 2000, 2002; Bosch, Kemp & tural ecosystem in which bees are crucial for Trostle 2006; Gruber et al.